CHRISTINE McVIE was a Perfect presence

Norman Warwick learns from top writers why

CHRISTINE McVIE was a Perfect presence

According to the excellent on line site The Music Afficienado, 1969 was a good year for British blues. While it lost the super trio Cream who finished their farewell tour at the end of 1968, many other bands released great blues-influenced records that year. It seems as if each band had its guitar superstar who defined their unique sound.. Ten Years After and Alvin Lee released two albums in 1969 on the Deram label. Free, with Paul Kossoff on guitar, also released their two first albums on Island. Leading them all was Fleetwood Mac with perhaps the best blues guitar player on that scene at the time, Peter Green. 1969 was their best year with the singles Man of the World and Oh Well and their last album with Green, Then Play On. Somewhat in the shadow of these successful bands was a lesser known band, led by guitarist Stan Webb. Chicken Shack was their name and in 1969 they saw minor success with their version of the song I’d Rather Go Blind.

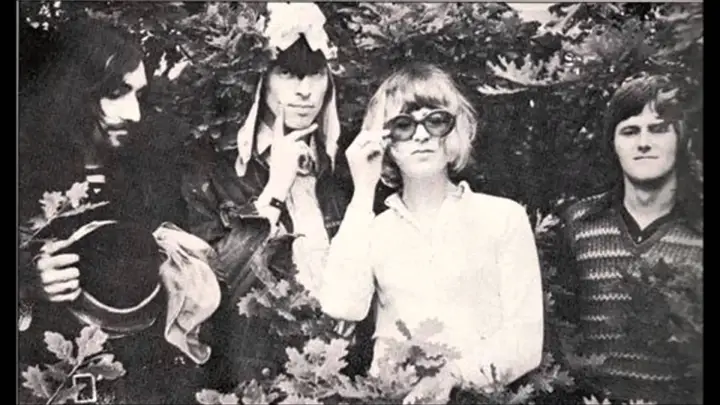

Chicken Shack (right) rose from a band Stan Webb (guitar), Andy Sylvester (rhythm guitar), Christine Perfect (Piano) and Chris Wood (Saxophone and Flute) started in Birmingham, named Sounds of Blue. Christine Perfect started as a bass and harmonica player, and then switched to piano when a new bass player was recruited. The band did not last long, and Chris Wood would later have a great career with Traffic, including their milestone album John Barleycorn Must Die. Christine Perfect left the band and the music scene in general, but when she got a call from Webb and Sylvester asking her to join their new band, she agreed and Chicken Shack was born. The band’s name was suggested to them by American blues pianist Champion Jack Dupree. It was black slang for a road-house blues venue.

Christine Perfect’s story is unique, as she was maybe the only female musician in the emerging British blues movement of the mid to late 60s. While switching to piano was not a problem for her, playing blues with the instrument she began to study as a child was a different story. She remembersed: “I didn’t have a clue as to what to do on piano. Stan Webb bought me a Freddie King album… and that was the beginning of my absolute love for the blues.” Perfect (left) was listening intently to Sonny Thompson, the legendary pianist who played and co-wrote many songs with blues guitarist and singer Freddie King.

While this was not her main focus at the time, Christine Perfect contributed a number of songs to Chicken Shack’s repertoire. On the band’s 1968 debut album 40 Blue Fingers, Freshly Packed and Ready to Serve, she composed and sang When the Train Comes Back and You Ain’t No Good. Two more contributions followed with the next album, O.K. Ken? with Get Like You Used to Be and A Woman Is the Blues, both of them co-written with Stan Webb.

Chicken Shack had strong ties to Fleetwood Mac in the late 60s. The bands first met at the Windsor National Jazz and Blues Festival in 1967, a three-day outdoor event with a line-up to drool over. A small sample of the participating artists included Pink Floyd, Yusef Lateef, Small Faces, The Move, The Pentangle, Cream and Jeff Beck. Chicken Shack were the new kids on the block and acted as the opening act for Fleetwood Mac who had better audience recognition due to its members work with John Mayall. This was Fleetwood Mac’s first incarnation, and they didn’t even have one of the band’s namesakes yet, as John McVie was reluctant to leave his steady position at John Mayall’s group. The two bands recorded their albums for the Blue Horizon label and shared the same manager and producer, the label’s founder Mike Vernon.

Christine Perfect loved the sound of Fleetwood Mac and came to see them playing live gigs when she had the opportunity. Her association with the band also included guesting on piano on Mr. Wonderful, the band’s second album from 1968. You can hear a spirited piano accompaniment she contributed to Rollin’ Man.

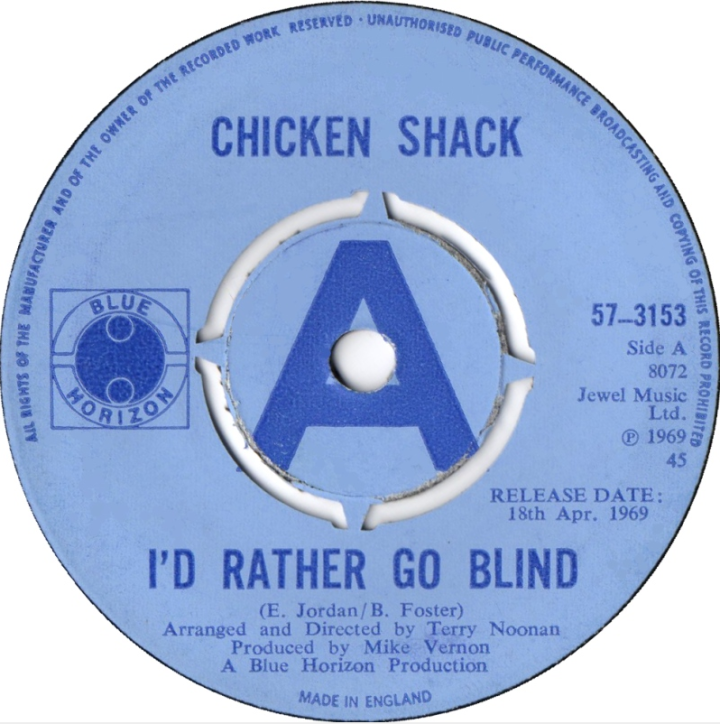

Following the release of Mr. Wonderful in August 1968, Perfect married John McVie and eventually left Chicken Shack with the intent of becoming a housewife. But before that she recorded with Chicken Shack the band’s most successful single, one that climbed to number 17 on the charts on Jun 14, 1969.

In February 1969 Chicken Shack went into the studio to record their version of I’d Rather Get Be Blind. Musicians on that single were Christine Perfect (Organ, Vocals), Stan Webb (Guitar), Andy Sylvester (Bass Guitar, Organ Bass Pedals) and Dave Bidwell (Drums). The single was recorded at CBS studio on New Bond Street in London, ran by engineer Mike Ross. Ross recorded all of Fleetwood Mac’s early albums, including the single Albatross, as well as The Who’s Happy Jack and I Can See For Miles. The horn section on I’d Rather Be Blind was arranged by Terry Noonan who also wrote the wonderful string arrangement for Fleetwood Mac’s single Need Your Love So Bad.

The song was partly written by Etta James, who in 1967 was one of the first artists on the Chess label roster to record at Muscle Shoals. In 1967 Leonard Chess was looking for a way to rejuvenate the label’s sound and could pick no better than the FAME Studios at Muscle Shoals, where rival label Atlantic recorded Wilson Pickett’s Mustang Sally and Aretha Franklin’s I Never Loved A Man and Do Right Woman. Etta came down from Chicago and in two days in August 1967 cut one of the best two-sided singles in the history of R&B – Tell Mama and I’d Rather Go Blind. Her performance of the song is probably the definitive one that most folks will identify with the song. Leonard Chess, a rather shrewd business man who could dish profanities left and right, almost came to tears when he first heard Etta James’ recording of I’d Rather Go Blind.

Soon after Chicken Shack’s single release Christine Perfect (now McVie) left the band, but she did not stay retired long. In the autumn of 1969 she was persuaded by Mike Vernon to record tracks for a solo album, in which she performed a different version of I’d Rather Go Blind. Later that year she won the Melody Maker Award for best female vocalist for her record with Chicken Shack. She was also awarded the title of having one of the top ten pairs of legs in all of Britain. A year later she won the award again for her solo album. A few months later she joined Fleetwood Mac and the rest is history.

McVie considered her writing with Fleetwood Mac much more mature than the songs she wrote for Chicken Shack and her first solo album. Indeed the songs she later wrote for Fleetwood Mac such as Songbird, Oh Daddy, Brown Eyes and the mega hits Over My Head, Say You Love Me, Don’t Stop and You Make Loving Fun are all great songs. Still, those 60s songs have their charm, and her delivery of I’d Rather Be Blind is one of the best in her career. It is soulful but in a British way reserved and devoid of vocal theatrics, a trap that some female soul singers fall into when they sing lyrics concerning being ditched by their man´´.

So, I was very sad to learn of the recent passing of one of my favourite female artists.

I first learned the news from a piece by Alex Hopper in American Songwriter, in which he said that

Christine McVie’s family has confirmed that the Fleetwood Mac singer-songwriter has died at age 79. Sharing a statement on her Facebook page they said, “On behalf of Christine McVie’s family, it is with a heavy heart we are informing you of Christine’s death. She passed away peacefully at the hospital this morning, Wednesday, November 30, 2022, following a short illness.”

The statement continued, “She was in the company of her family. We kindly ask that you respect the family’s privacy at this extremely painful time and we would like everyone to keep Christine in their hearts and remember the life of an incredible human being, and revered musician who was loved universally. RIP Christine McVie.”

Her Fleetwood Mac band-mates also paid tribute to McVie´s writing, “She was truly one-of-a-kind, special and talented beyond measure. She was the best musician anyone could have in their band and the best friend anyone could have in their life. We were so lucky to have a life with her. Individually and together, we cherished Christine deeply and are thankful for the amazing memories we have. She will be so very missed.”

McVie joined Fleetwood Mac in 1970 alongside her husband at the time, John McVie. She penned some of the group’s most enduring hits like “Songbird,” “Little Lies,” “Over My Head” and “Say You Love Me.”

After adding on Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham, an aspirant duo overheard in a studio by Mc members, the group became one of the most prominent figures in rock in the ’70s and ’80s. Their 1977 LP, Rumours, became one of the best-selling albums of all time with the help of McVie’s “You Make Loving Fun” and “Don’t Stop.”

McVie took a hiatus from the group in 1998 with the rest of the members thinking it was not likely she would ever rejoin the group. Nicks said at the time, “She went to England and she has never been back since 1998 […] as much as we would all like to think that she’ll just change her mind one day, I don’t think it’ll happen […] We love her, so we had to let her go.”

Despite their reservations, McVie did rejoin Fleetwood Mac in 2014 for their On With The Show Tour and remained a member until her death.

Knowing that other great music writers would be commemorating Christine McVie in any number of ways, I turned to the excellent Geoffrey Himes at the Paste on-line magazine, who along with Jacob Uittii, Tina Benitez Eves and the afore-mentioned Alex Hopper is among my most trusted writers on the American genres I so love.

Mr. Himes´ published on 1st December 2022 piece was titled Remembering Christine McVie: Hiding In Plain Sight, a phrase that immediately captured her low key genius in constantly delivering new songs, and adding great presence to recordings as well as a constant sense of reliability in stage shows that sometimes saw the spotlight being fought over by other members.

Or, as Geoffrey Himes more accurately put it;

In the world of Fleetwood Mac, Christine McVie was the normal one. She didn’t present herself as the white witch of Wales. She didn’t hire a college marching band to become the rhythm section for an experimental rock single. She didn’t attach electric drum pads to various parts of her six-foot-six frame to become a dancing percussion kit. She never left the band in the middle of a tour to join a religious commune.

McVie just sat there at the keyboards—dressed in sensible clothes, her blonde sheepdog bangs hanging over her girl-next-door face—and sang some of the catchiest pop-rock songs ever written. Sometimes she supplied the cushiony harmony to a song written by one of her band-mates, but the best songs were often those she wrote and sang herself, her alto somehow sumptuous and off-handedly friendly at the same time.

Now she’s gone. She died Wednesday at age 79 from an undisclosed illness. “I didn’t even know she was ill until late Saturday night,” band-mate Stevie Nicks wrote on Instagram. “I wanted to get to London, but we were told to wait.”

She died as one of her compositions was proving the enduring appeal of her music. A current TV commercial for an electric car shows friends in that vehicle singing along to “Everywhere,” a song that’s hard not to join in on. The verse gently swings over a thumping rock beat, as McVie’s unhurried vocal confesses her love.

But when the chorus comes along with that “Oh, I…,” the melody suddenly leaps an octave, uncannily reflecting the lift of the heart during the early stage of any infatuation. The rest of the lyric, “I want to be with you everywhere,” merely makes explicit what the music has already told us. The song’s inherent drama, boosted by the ad, returned “Everywhere” to the charts this fall: #3 on iTunes.

McVie created such musical echoes of universal emotions again and again from her early days with the British rock’n’soul band Chicken Shack and the early, British-based version of Fleetwood Mac through the multiple-platinum glory days of the American-based version of the Mac. McVie made three solo albums, one of them under her maiden name of Christine Perfect, but her best vehicle was always Fleetwood Mac—even her enjoyable 2017 duo album with Lindsey Buckingham was meant to be a Fleetwood Mac album until Nicks declined to participate.

When that band released its Greatest Hits album in 1988, eight of the 16 songs were written by McVie, while Nicks had five and Buckingham three. McVie was the more reliable songwriter, but her bandmates got more media attention. This was inevitable. Nicks and Buckingham, a romantic couple who joined Fleetwood Mac in 1975 and broke up a year later, brought the kind of flamboyant drama journalists can’t resist. But McVie was the band’s secret weapon, the glue that held things together when they were threatening to fly apart, the melodic genius hiding in plain sight.

“Christine’s a great songwriter with a great pop voice,” Buckingham told me last year. “She’s the middle ground between Stevie and me, because she’s grounded in her musicianship while Stevie’s more ethereal. If you take Christine out of the equation, you get a stylistic polarity between Stevie and me. When she’s there, she provides a middle that holds the band together.”

Melody remains the most mysterious element in popular music. Why does one sequence of notes grab our attention as a similar sequence doesn’t? And yet some songwriters have a knack for coming up with such sequences repeatedly: Richard Rodgers, Paul McCartney, Stevie Wonder, Billy Strayhorn, Carole King and Christine McVie. It’s a gift that’s hard to explain but impossible to deny

But there’s more than melody going on in McVie’s songs. Beneath the exhilarating rise and fall of the vocal line, beneath the gushing of emotion, there’s a toughness, a no-nonsense push that she’s had since her early days in the world of the British blues revival. Her first chart success, after all, was her vocal on Chicken Shack’s 1969 cover of “I’d Rather Go Blind,” recorded two years earlier by soul legend Etta James for Chess Records. It was Fats Domino who lured her away from her classical piano lessons as a girl in England’s Lake District.

It was in that early London scene that she met John “Mac” McVie, the bass player who had formed the British blues revival band Fleetwood Mac with drummer Mick Fleetwood. Christine Perfect married McVie and took his name, and when virtuoso guitarist Peter Green took too much LSD and ran off to a religious commune, the newlywed keyboardist was invited to take his place.

When American singer-guitarist Bob Welch replaced another AWOL guitarist (Jeremy Spencer) in 1970, it shifted the band away from its bluesy, London origins towards a breezier California pop. Welch wasn’t the songwriter that Buckingham and Nicks would be, but this transition to pop encouraged Christine McVie’s melodic and harmonic instincts and made possible the glories to come.

When Welch resigned in 1974, the remaining three members, Fleetwood and the two McVies, went looking for replacements. Fleetwood remembered that while checking out the Sound City recording studio, he had by chance heard a track by a duo called Buckingham Nicks, who were recording at the facility. An invitation was extended, and the band’s classic line-up was assembled.

As the new line-up recorded its first album, eventually released as Fleetwood Mac, they realized that Buckingham was more than just another hot-shot guitarist in the lineage of Green, Spencer and Danny Kirwan. Buckingham also had a knack for massaging promising but unfocused songs into pop gems.

“It became apparent to me that one of my jobs was to be producer/musical director,” he told me. “You had these three different writers who were each very different in their style. You had Christine and Stevie, whose songs needed some augmentation from me as a producer to reach their potential. John McVie was so versed in the blues, he was a bit ambivalent about this California thing. But somehow all these pieces jelled into one thing.”

McVie benefitted from Buckingham’s help. Her songs on Fleetwood Mac had a snap and clarity they’d never had before. Three of her songs on the album were released as singles, the non-charting “Warm Ways,” the #20 “Over My Head” and the #11 “Say You Love Me.” These slowly improving chart figures reflected the slow build of the band from blues-rock footnote to pop juggernaut. It took a while, but the album eventually sold four million copies and prepared the way for Rumours.

By the time they recorded that follow-up record, however, the band had turned into a soap opera. Nicks had left Buckingham and was having an affair with Fleetwood. The McVies had split up, and Christine was having an affair with the band’s lighting director Curry Grant. Christine wrote the song “You Make Loving Fun” about Grant but told her ex that it was about her dog. She wrote “Don’t Stop” for John McVie to encourage him to overcome his drinking problems.

All this backstage drama helped to hype the album, but it really had little to do with the quality of the songs. “You Make Loving Fun” would be as joyfully romantic whether it was about a dog or a lighting director. It’s the tension between McVie’s held-out vocal syllables and her funky clavinet riff, between the push-and-pull verse and the chorus reverie that make it so effective. “Don’t Stop” is such a contagious anthem that its punchy advice worked as sobriety advice or as a campaign theme song for Bill Clinton in 1992.

Rumours has reportedly sold 40 million copies worldwide, making it one of the best-selling recordings of all time. It was so successful, in fact, that it follow-up Tusk seemed a disappointment when it sold only four million copies. Many critics admired Buckingham’s leaner, more jagged production, but several label executives and band members were less happy with the sales results. McVie, however, proved as reliable as ever, adapting to the new sound effectively on “Think About Me” and contributing another old-fashioned, mesmerizing ballad in the form of “Never Make Me Cry.”

The band had one more triumph up its sleeve. Tango in the Night, released in 1987, sold 15 million copies and yielded four top-20 singles, including two written and sung by McVie: “Little Lies” and “Everywhere.” It would be the last studio album to feature the classic line-up, for Buckingham quit the band soon after. Nicks left in 1991, and McVie left in 1998, retiring to rural England to get away from the touring life. She would return in 2014 for a live album and subsequent tours, but there would never be another studio album.

Christine McVie didn’t have the witchy charisma of Nicks nor the experimental edginess of Buckingham and Fleetwood, but when we’re humming a Fleetwood Mac song, it’s more than likely that McVie wrote it.

After Mr. Himes´ perfect final point I sighed a long sigh for the passing of Ms. Mc, Vie and for the body of work of her and her bandmates. I turned sadly to social media to see if any friends had posted any thoughts, and I found an absolute delight shared by a former colleague from when I worked in the UK before retiring here.

Alyson Brailsford is still, I think, a member of the Halle Choir and I´m sure is still regaling Rochdale audiences with her own beautiful voice and wide ranging selections of hymns and carols, traditional and contemporary folk and dialect songs.

The post she shared was an absolutely heartfelt version of Songbird sung at the piano by a woman who seemed to dub herself as a ¨Geordie Ginger Singer´ but was referred to by Alyson as Ellen. It was a beautifully poignant and almost eerie interpretation with what sounded like some double-tracking going on,……very, very moving, and something that I know will come to mind now whenever I hear Christine McVie´s music in the future.

Thanks for recording Songbird, Ellen, and thanks ever so much for sharing it Alyson Brailsford.

And thanks for everything, from all of us, Christine McVie !

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!