ANY FRIEND OF JAZZ IS A BUDDY OF MINE

ANY FRIEND OF JAZZ IS A BUDDY OF MINE

by Norman Warwick

Legend has created a biography of Buddy Bolden that has him pretty much regarded as the first person to ever play jazz. This legend sprang up about as archivists and historians began to seriously research his life (about 30 years after he stopped playing). Stories were whispered into shape about how he had been the editor of a scandal newspaper, ran a barbershop and played his cornet so loud that he eventually blew his brains out.

Its all reflection and obfuscation, sunlight and mist and, as Paul Simon might have put it, hints and allegations. A Robert Johnson dealing with the devil for a handful of songs, a Townes Van Zandt heading through them hills and gone, Bolden has become both eternal and ephemeral.

In his book, Billy Bolden: The First Man Of Jazz, author Don Marquis attempts to sort out the fact from the fiction and, according to book reviewer Kevin Lowe. he succeeds superbly well.

´Quite simply I could not put this book down,´ said Lowe, in 2013, some thirty five years on from the book´s first publication in 1978.

´You would think that the amount of primary sources available to the author would be scant and could not possibly warrant a full biography on such a vague character as Bolden. Yet by digging up birth, marriage and death certificates, police records, old city maps, personal letters and newspaper stories from the time, Marquis has managed to piece together a full and fascinating story.

His research was carried out in the nineteen seventies so he also had access to some of the people who were first-hand witnesses to the goings-on in New Orleans at the turn of the nineteenth / twentieth centuries. This revised edition of 2013 provides an additional epilogue from 2005 and gives an insight into how the author located some descendants of Bolden and organised a ´fitting memorial´ for him in New Orleans. It also lays to rest the myth of the missing recording that he supposedly made in 1897. If it did exist it has surely been destroyed. How the first man of jazz sounded will remain to be resolved only by our imagination. And perhaps it should.

I like the sound of Marquis and I like the sound of Kevin Lowe, the man who reviews his book. Between them,, they have convinced me that I, an uninformed fan who always stands at a jazz club door with some trepidation, would also have liked the sounds of Billy Bolden.

Donald Robert Perry Marquis (right) was of this earth from July 29, 1878 to December 29, 1937 but his search for Bolden, and the review of that search by Lowe somehow re-shape him into a contemporary 21st century investigative journalist. He was, in fact, an American humorist, journalist, and author. He was variously a novelist, poet, newspaper columnist, and playwright. He is remembered best for creating the characters Archy and Mehitabel, supposed authors of humorous verse. During his lifetime he was equally famous for creating another fictitious character, The Old Soak, who was the subject of two books, a hit Broadway play (1922–23), a silent movie (1926) and a talkie (1937).

We can assume from that resumé, can we not, that this man who was writing a biography in search of sorting fact from fiction was aware of the power of those two apparently opposite forms? This biographer in search of a man behind a myth had already spent most of his life creating characters and seeking to present them as corporeal.

A search of Wikipedia, a landscape on which fact and fiction are never confused will show you Marquis´ lengthy career as a successful journalist and successful writer in all forms of fact and fiction. In fact, the entry for Marquis is nearly as long and dense as that for Billy Bolden. I place that information here, of course, only for your consideration and have no diea what you might make of it.

Kevin Lowe, at least through Google, remains as enigmatic in the background. By looking at the web site of Jazz In Europe to which he was an occasional contributor though I could only ascertain through their pages that he lived for a time in Spain. Perhaps my interest in him is heightened because information on him, at least in my usual areas of research, so scarce.

There are those who would suggest that The Birth Of Jazz is more accurately defined in a book of that name by Daniel Hardy. The book is certainly fastidiously researched, and full of empirical evidence supporting the veracity of its stated facts.

And yet, I often find that I get to better know, or at least create a clearer mental picture of, others from musical references and casual conversation. Through the opinions of others we vaguely come to think we know others we don´t know at all.

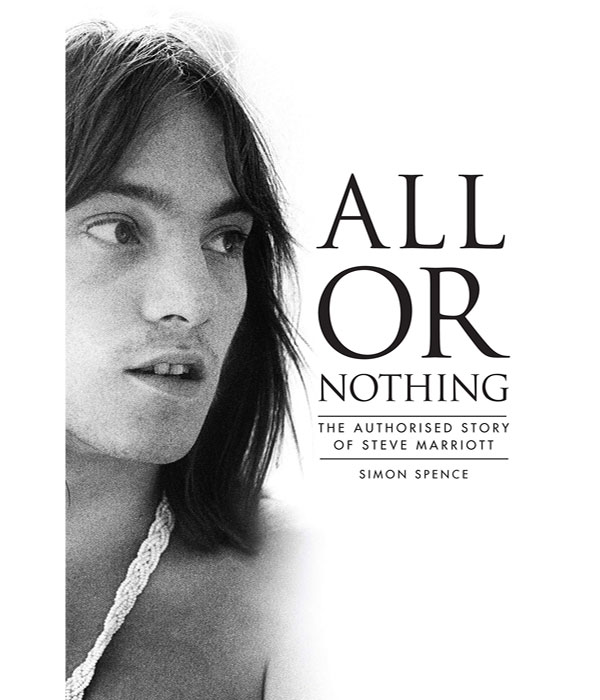

For instance, the recent publication of All Or Nothing, (lent to me by Larry Yaskiel, a former record label executive now honorary editor of Lancelot magazine), that is a biography of kinds by Simon Spence of the late Steve Marriott, proved instructive. It is a stitched together narrative created from more than 125 interviews conducted by the author with people who knew Marriott and were directly involved in major incidents in his too brief life. Reliable narrators all? Whatever the case, their interwoven narratives create a comprehensive picture.

Whatever Marquis tells us about Bolden, and however strongly Lowe commends him, there are other sources available. How accurate they may be should not be confused with how enjoyable they might be.

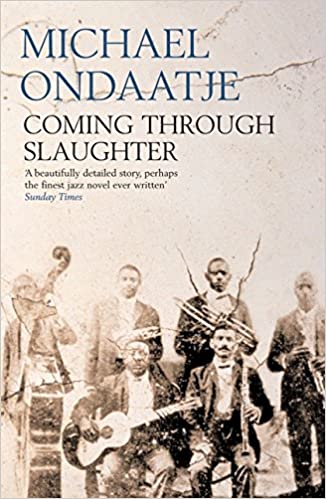

The wonderful author, Michael Ondaatje, he who so wilfully conceals from readers what we think has just been revealed (read the book and see the film of The English Patient) also wrote Coming Through Slaughter. During the nineteen eighties an adaptation of the novel was staged at Harvard’s Hasty Pudding Theater. The music was scored by Steven Provizer and the production was directed by Tim McDonough.

Ondaatje´s work was the novel that introduced me to jazz, or at least was the first work that ever made me want to further investigate the genre. It seemed almost that Ondaatje was creating a role for Bill Bolden: the myth that represents the art form that is jazz,

Australian female novelist Nikki Gemmel, author of With My Body, published by Fourth Estate has revealed in a piece in The Independent that Coming Through Slaughter was her ´book of a lifetime.

´I discovered it´, she recalled, ´just as the cement was setting around the idea of making the dream, writing, an actual career (to the horror of my coal-miner father, who, when hearing of my vaultingly ridiculous ambition, responded – “waste of time, books”.) Ondaatje’s slim, early tome was introduced by a university lecturer, a failed and depleted writer himself, and it entered my world like a depth charge of possibility. I’ve carried my battered Picador paperback around for decades; the pages, now, are almost greasy from being thumbed, flipped, dog-eared and scribbled upon.

What is it? Not sure exactly, and that’s what makes it so damned exciting. It’s an account, .. of the life of jazz musician Buddy Bolden, a cornet player in New Orleans in the early years of the 20th century. Not an area of interest for me generally, but my God, you’re entranced by this world that Ondaatje creates. It’s a daring, audacious little book that defies categorisation – experimenting with fiction and non-fiction, photography, and dramatic changes of tense and voice. Bolden was known for his dazzling improvisations and there’s something of that energy in it.

This book has been like a prod over the years: to not necessarily take the easiest path; to write with energy and honesty; emotional truth. And beauty, always that. It’s also deliciously grubby and vulnerable and ultimately – what all great novels are – moving. Heartbreaking, in fact. Don’t all writers want to conjure up a book that wrenches the heart at some point? It’s taught me several lessons as a writer: the importance of a strong narrative to propel the reader forward and the need to evoke some kind of empathy with the protaganist. ‘Coming Through Slaughter’ moves me deeply.

It’s fearless, dangerous writing, something I’m addicted to and aspire to in my own work. Over the years, I’ve recognised it in books by Anne Carson, Michel Houellebecq, Marguerite Duras, Dave Eggers and Ali Smith. It intrigues me, now, that this is an early work by Ondaatje. There’s something so youthful and captivating about the energy, when you’re roaring through life, addicted to the new, to risk. I want to keep recapturing that exhilarating, effortless feeling in my own books, but it’s so hard, as the years go on, as life closes in around you and you have to think about mortgages and sellable books; about making a living out of this crazy life. But I’ve tried to go back to the fundamentals of its audacious energy with my new book, ‘With My Body’.

So all I can say is thank you, Mr Ondaatje, for this bewitching tome. It’s been like my tuning fork over the years – very different to my own writing, but your book sets the bar for me in terms of energy and daring and risk-taking. All I need is a paragraph from its deliciously audacious pages to get me in the mood, and I’m off and racing´.

Kircus review had this to say on publication:

´Ondaatje is a Canadian poet (the stunning Collected Works of Billy the Kid), and his first full-length stretch of prose is one of the more successful resolutions of a poet/novelist identity crisis. The life of pioneer jazz musician Charles (Buddy) Bolden, 1876-1931, gives Ondaatje his charged, raw material: Buddy’s hyperactive New Orleans good times—daytime barber, nighttime cornet man, fulltime editor of The Cricket, a gossip-news-crime sheet for the District—and his descent into the bad times when ´he didn’t want to meet anybody he knew again, ever in his life´. When that happens, Buddy leaves wife Norah and two kids, disappears for two years (an uneasy menage a trois with a married couple), and, tracked down by old cop-friend Webb, returns in time to join a parade, go berserk, and spend the last 25 years of his life in East Louisiana State Hospital—´Dementia Praecox. Paranoid Type.´

The narrative mosaic incorporates pronoun-switching, flashes forward, back, and sideways, slivers of authentic documents and interview transcripts, free verse, and free association, but, with near-miraculous control, Ondaatje fends off any artsy confusion about who, where, when, or what is happening. That’s his triumph; his downfall is that, despite the lusty milieu, the freewheeling passions, and the vivid, fact-based characters (like Bellocq, photographer of prostitutes and self-arsonist), Buddy Bolden’s life never seems as real, immediate, or important as the elaborate variations on it´.

I think these are rather wonderful reviews and I love that final point even in the sentence even as I decide that it misses the final point. For me the great success of Ondaatje´s Coming Through Slaughter (a title inspired by place-name but so damning, perhaps, of what we have all conspired to do to the memory of Bolden), is that he reminds us of what successive generations have done to Bolden. They, we, have reduced Bolden´s life to being less real, less immediate and even less important than the elaborate variations we have imposed on it.

The high esteem in which I held the book was represented in the way I attached some of the attitudes of Coming Through Slaughter into writing a short performance piece about Townes Van Zandt which Pam Mckee and I performed a few times as Just Poets, and also utilised as a lesson plan for our creative writing classes.

However, that so many piled acclaim on to Ondaatje´s work based, albeit loosely, on Buddy Bolden´s ´life´, does not mean the book was universally acclaimed.

A reader review posted on line read of how the reader ´had been looking forward to reading this novel, enticed by the promise of lyrical writing and a look into the life of New Orleanian jazz musician Buddy Bolden. All I found was a rambling, imitative style (think Nabokov, Faulkner, but less tightly written), and incessant focus on sex and women-as-sex-objects; almost every sex scene included violent language and felt misogynistic. While a motif of sex and sexuality would have been nothing to complain about in and of itself, it seemed a shame that this motif so utterly trumped the inclusion of Bolden’s music, and that the female figures in the book were continually robbed of power/objectified/subjected to rhetorical violence by the writing style´.

That reader´s comment on the portrayal of women in Ondaatje´s book foreshadows, of course, similar arguments about two or three biopics of Billie Holiday-

With jazz now ´over a hundred years old´ conventional histories might briefly mention Buddy Bolden, leader of the first jazz band, but the actual circumstances of its birth are rarely described. This somehow strengthens my suspicions that Billy Bolden, the myth, is often used as a shorthand to reference a birthing, of which we have no hard evidence, of jazz-

Because the only recording made by the band was lost, it has been assumed we can never know how the first cries of new-born jazz sounded. The truth is that there were many witnesses to its birth and childhood. By patiently gathering the many scraps of information left by them, it is possible not only to create a chronological account of its emergence, but also to describe the music itself.

Reviewers of The Birth Of Jazz seem agreed that Daniel Hardie outlines when, where, and how jazz came into being and who its creators were. All that is left is to recreate the repertoire and performance style of the time. In 2004, Hardie formed a repertory orchestra to perform jazz ´as it was played during its first ten years´. He describes the research needed to revive the music and how the Buddy Bolden Revival Orchestra was established. He also gives an account of the resulting performances and how they illuminate our understanding of the music itself. His findings are surprising. The Birth of Jazz is a must for all lovers of jazz

A biopic of Billy, simply named Bolden, would probably not offer those satisfied readers the same amount of pleasure. The film starred Ian McShane, playing a jazz man, but viewers could not be sure of his identity.

Leon Nock, writing in Jazz Journal at the time was unconvinced by the film.

´I learned everything I know about Buddy Bolden from Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya´, he informed us in opening his piece.

´That is the one indispensable book about jazz from soup to nuts, co-edited by Nat Hentoff and Nat Shapiro and published in 1955. A new film, Bolden, written, produced and directed by Dan Pritzker and released in the US in May 2019, added precisely nothing to what I gleaned from (their book), for the fact remains that precious little is known about Bolden. This makes the film more an impression of a black cornet player born in New Orleans in the 19th century. That was where Bolden was active from around 1895, achieving both fame and respect before being committed to the Louisiana State Asylum where he died in November, 1931´.

Jeff Winke in All About Jazz in 2013 reminded us that the roots of American jazz twist, turn, and spiral all the way back to the turn of the century… not this century, but the last century.

In the 20th century’s first decade down in New Orleans, the story is told that one could frequently hear a cornet (which is similar to a trumpet) squawking loudly from the park bandstands and through dance hall windows. With no formal training, Charles Buddy Bolden created a unique improvising style with his horn. Essentially, he paved the way for jazz by arranging rural blues, spirituals and ragtime music for brass instruments. The legend has it that as he heard traditional songs, he would reshuffle them with his own improvisations, creating a powerful new sound.

Buddy Bolden kick-started his career by performing in the Papa Jack Laines Reliance Brass Band. Papa Jack Laines is often credited as the Patriarch Of Jazz. Bolden formed a number of his own bands in the mid-1890s, seeking a perfect amalgam of sound. Toward the end of the century he found it. The Buddy Bolden Band consisted of cornet, guitar, trombone, bass, two clarinets and drums. His band played downtown New Orleans in crowded clubs located in the unsavory and infamous red-light area of Storyville.

We should remember thatFrom 1900 to 1906, the Buddy Bolden Band was the top draw in New Orleans. Not unlike rap singers today, Charles “Buddy” Bolden upgraded his status and identity first calling himself “Kid” and later… “King” Bolden. During this time, he ravenously pursued two interests: alcohol and women.

With fame, responsibility, new bands competing against him, and the struggle to keep his music fresh, innovative and alive, Bolden hit the wall in 1906. Depression, hopelessness, and the dark allure of alcohol brought on bouts of severe headaches and paranoia (an erratic fear of his cornet probably didn’t help his music). He became so “brainsick” that the doctors confined him to bed.

In 1907, Bolden held his last public performance with the Eagle Band at the New Orleans Labor Day parade. During the parade, he apparently started screaming at ladies near him and frothed at the mouth. His condition worsened and he was sent to the lunatic asylum. In and out of the asylum, his hallucinations and violence worsened until he was permanently placed in the State Insane Asylum in Jackson, Lousiana on June 5, 1907. The asylum remained his home for more than 25 years, before he passed away in a state of utter dejection and insanity. His body was buried in Holte Cemetery, a pauper’s graveyard located in New Orleans.

Unfortunately, there are no surviving recordings of Buddy Bolden playing. From those who knew his music, he was said to have played a ´loud blue tone and improvised much of his music.´ Considered by many as the founder-father of jazz, Bolden has carried the moniker of the first king of New Orleans jazz and was the inspiration for such later jazz greats as Joe “King” Oliver, Kid Ory, and Louis Armstrong.´

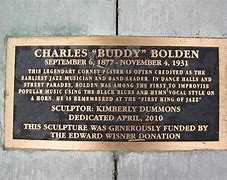

His life story has been re-written, revised and a statue of him (left) has been created, and put in place, and those of us with fanciful imaginations see that as representing the very time and the very portal where jazz was made open to the world.

So, the jury may still out on the verdict as to what kind of guy Buddy Bolden might have been, as verdicts are still awaited in sitting rooms and court rooms and jazz clubs around the world on the question of what, precisely, is jazz.

Buddy seems to be Mr. Tambourine Man, a pale rider, of maybe just the guy you see on the tube with an instrument in his arm.

Buddy is the ghost in the music of jazz, as Johnson is the ghost of the blues as Hank Williams is the ghost of Americana.

Meanwhile, here in the real world we have received another missive from our friends at Jazz In Reading who offer congratulations and wish good luck to New Zealand saxophonist Lucien Johnson, who has been shortlisted for the Recorded Music NZ Jazz Awards – there are only two categories and Lucien is in both of them.

Lucien is up for Best Jazz Artist and Blue Rain, from his Wax///Wane album, is up for Best Jazz Composition. As his European media contact, we’re biased but this is well-deserved. The results are due later in June. Meanwhile you can check out Wax//Wane here. It’s available on vinyl too now but shipping/import duty from NZ might carry a Brexit-inspired financial health warning.

Exciting news from Fergus McCreadie – the pianist’s trio (right) streams a Glasgow Jazz Festival concert, including a specially commissioned lockdown piece, on June 18 (info here). The same day, they release a new video. There’s also still time to catch their Perth Festival stream (info here). And there’s more: coming up on July 2 they play a real live proper gig, with people allowed, as part of the East Neuk Festival in Fife (info here).

The Scottish National Jazz Orchestra’s Where Rivers Meet, featuring truly amazing arrangements, brilliant ensemble playing and fabulous soloists including Konrad Wiszniewski (left), is still available to view at your leisure until August 15. A “blues-driven, gospel-fed” experience (Jazz Journal). You can find out more here.

Playtime continue to create music online, with recent sessions going ahead at Pathhead Village Hall, which allows the musicians to play together in the same room, if not in front of a live audience just yet. The programme for these Friday live streams is invariably announced at relatively short notice but you can find out what’s happening via Twitter (@OhPlaytime or @rabjourno) or Facebook.

Tina May (left) has a live stream coming from Riverside Arts in Sunbury on June 1 (info here). The New York radio programme A Broad Spectrum has been featuring Tina’s music recently, especially the songs for which she wrote the lyrics. She’s beginning to add live gigs to her diary, so it’s worth checking in on her Live Dates page here.

Looking ahead, Tommy Smith’s solo saxophone concert in Lichfield Cathedral takes place on Thursday, July 15. The concert is one of several Tommy’s planning to give in cathedrals and churches, where the acoustics lend themselves to atmospheric and unhurried improvisation. Tommy’s recent release on Bandcamp, Solow gives a good indication of the moods to expect in these concerts. He’s recently been adding Gaelic waulking songs to his solo repertoire and he can draw on a wealth of knowledge of the jazz canon, choosing melodies in situ and sharing his fabulous tone production and creative imagination.

were the senders of the above news items. They provide a great listings service and have a comprehensive news, interviews, previews and reviews service on their excellent web site and their ethos was the inspiration for a few friends and i forming our own small collaboration of jazz writers )see below)

This piece was cut and pasted, stapled and paper-clipped together by Norman Warwick, (left) the owner and editor of Sidetracks And Detours and was brought about as much by his admiration of Michael Ondaatje, writer and poet, as by his liking for the music of Buddy Bolden, pioneer and jazz man. It does not keep near to telling the story of either man, but might come close to creating a story about the relationship between the turn of the century jazz player and a novelist, poet, writing a hundred years later,

Norman is a one of the four founder members of the Joined Up Jazz Journalists, (JUJJ) formed in 2020 with Steve Bewick and Gary Heywood-Everett who work together as, respectively, presenter and researcher and historian for Hot Biscuits which you can hear on

www.fc-radio.co.uk and Susana Fondon who is a music journalist at Lanzarote Information on-line for which Norman also writes a weekly arts column as well as his daily blog at https://aata-dev where you will find scores of other jazz related works among the easy to trace archives.

Sidetracks And Detours is always pleased to receive news, interviews, previews and reviews of arts events in the world. If you would like to submit a piece for consideration please attach it as a Word document in an e mail to normanwarwick55@gmail.com. We will try find space for any appropriate work, and will fully attribute such inclusions, so please feel free to include a short bio and jpeg of yourself if you wish, We do have a fairly extensive photographic collection but if you wish to provide images to complement please attach them in jpeg form ain a zipped folder.

We look forward to hearing from you.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!