BILLIE´S BLUES ECHOING STILL

BILLIE´S BLUES ECHOING STILL

by Norman Warwick

sources: article by Natalia Keogan in Paste on-line magazine

Lady Sings The Blues is a 1972 American biographical drama film directed by Sidney J. Furie about jazz singer Billie Holiday, loosely based on her 1956 autobiography which, in turn, took its title from Holiday’s songs. It was produced by Motown Productions for Paramount Pictures. Diana Ross (a Motown artist) portrayed Holiday, alongside a cast including Billy Dee Williams, Richard Pryor, James T. Callahan, and Scatman Crothers. The film was nominated for five Academy Awards in 1973, including Diana Ross for Best Actress in a Leading Role.

However, despite its commercial success, reviews for the film were somewhat mixed.

´My first reaction when I learned that Diana Ross had been cast to play Billie Holiday was a quick and simple one´, said Roger Ebert, a leading critic of the time., writing at https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/lady-sings-the-blues-1972

I seemed to remember Ebert was the first film critic to win the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism and on line searches of Wiki and such reminded me that Roger Joseph Ebert (left) was an American film critic, film historian, journalist, screenwriter, and author. He was a film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. He was variously described as ´the most powerful pundit in America,” ´´ the best-known film critic in America.´

´I didn’t think she could do it,´ he said. ´I knew she could sing, although not as well as Billie Holiday and certainly not in the same way, but he couldn’t imagine Diana Ross reaching the emotional highs and lows of one of the more extreme public lives of our time. But the movie was financed by Motown, and Diana Ross was Motown’s most cherished property, so maybe the casting made some kind of commercial sense.´

´All of those thoughts were wiped out of my mind within the first three or four minutes of Lady Sings The Blues´, he wrote, ´and I was left with a feeling of complete confidence in a dramatic performance. This was one of the great performances of 1972.

And there is no building up to it. The opening scene is one of total and unrelieved anguish; Billie Holiday is locked into prison, destitute and nearly friendless, and desperately needing a fix of heroin. The high, lonely shriek which escapes from Ross in this scene is a call from the soul, and we know this isn’t just any “screen debut” by a Top 40 star; this is acting.´

So Ebert paid tribute to the acknowledged genius that was Billie Holiday and to the previously unrevealed talents of Diana Ross as an actress.

Nevertheless, it was probably inevitable that the movie itself would follow the tried-and-true formula of most of the musical biographies of the previous twenty years.

´The genre was well-established, and since most of the musicians they’ve made movies about have had unhappy private lives, there’s the problem of making downhill look like uphill, at least sometimes,´ Ebert explained. ´This is often handled (and it is again this time) by showing the performer hitting bottom, rebounding into the arms of friends, being nursed back to health, and making a spectacular comeback performance at Carnegie Hall, or at least the Palace.

Lady Sings the Blues has most of the clichés we expect—but do we really mind clichés in a movie like this? I don’t think so. There’s the childhood poverty, the searching for love, the unhappy early sexual experiences, the first audition, the big break, the years of climbing to the top, the encounter with hard drugs, the fall, the comeback, the loyal lover … we know the scenes by heart.

The movie is filled with many of the great Billie Holiday songs, and Ross handles them in an interesting way. She doesn’t sing in her own style, and she never tries to imitate Holiday, but she sings somehow in the manner of Holiday. There is an uncanny echo, a suggestion, and yet the style is a tribute to Billie Holiday, not an impersonation. The songs do slow the movie down quite a bit, and it feels long at over two hours, but the Billie Holiday music is really the occasion, so I suppose I shouldn’t complain.´

Reading Ebert´s report again in research for this article I was certainly made to feel more determined than ever to place artists and their art in as clear a context as possible. Such contextualisation actually becomes blurred and made more difficult by the passing of time and the re-writings of history and the revisions of social attitudes.

We have discussed many times on these pages on whether we should stand by the art even if disapproving of its artist´s lifestyle, and that question is being raised again now by renewed interest in the work of Billie Holiday.

Just too late to make the pages of our Billie Holiday (left) feature during our Joined Up Jazz Festival I was finally able to watch the Sky premier of The United States Versus Billie Holiday. By the end of the viewing I was suffering from blurred vision, confused by the re-writing of history and the revision of social attitudes.

I was, however, dazzled by the performance of the actress in the title role, (as Ebert had been by Ross), bemused by all my counts of ´Oh, he´s meant to be so and so,´ on seeing actors posing as Billie´s players supporting her on stage, and was appalled by the duplicity of government agencies. I had mixed emotions of sympathy for Billie whenever (nearly all the time) she was being bullied or harrassed and anger at her whenever she passed on that bullying and harassment to others.

I was left doubting the reliability of the narrative with its elliptical chronological loops and as the credits rolled I wondered whether the film had been made to celebrate Billie or to laud the agencies who tried so hard to rid us all of the scourge of drugs. I was questioning what the film said about the jazz scene of Billie´s era, and the social conditions surrounding it.

As I was pondering this, over the next couple of days, with all the urgency and lack thereof that sixty seven years of age and an idyllic lifestyle of semi-retirement brings, I stumbled over an on-line article in that wonderful arbiter that is Paste magazine.

Natalia Keogan is a Queens-based writer who covers film, music and culture, with particular interest in the horror genre and depictions of sexuality and gender. You can read her work in Narratively, Filmmaker Magazine and Paste, at

and find her on Twitter. Her thoughts on the film not only echoed my own questions but also provided me with many answers that might have taken weeks for my befuddled brain to figure out.

Keogan wrote that The United States vs. Billie Holiday opens with a contextualizing title card detailing the U.S. government’s inability to ban lynching outright, but bafflingly withholds Lady Day’s haunting rendition of Strange Fruit for the majority of its runtime.

Instead, the overlong and tedious film opts for rudimentary Oscar-bait trappings and a crudely voyeuristic portrayal of the renowned jazz singer—a commanding performance by first-time actress Andra Day notwithstanding.´

Those opening paragraphs of Natalia´s, speaking of the film as being of rudimentary Oscar-bait trappings, overlong, tedious and crudely voyeuristic, yet giving a firm nod of approval to its leading lady, certainly were enough to earn five stars from me for her review. Natalia Keogan, though, is obviously way beyond requiring commendations from the likes of me and she went on to vigorously explore further the film and the reasons behind the making of it.

´Based on a chapter of Johann Hari’s non-fiction book Chasing the Scream: The First And Last Days Of The War On Drugs, the film stretches a few thousand words of text into a punishing two-hour runtime,´ she says. ´Despite the plethora of shocking and relevant details in Hari’s book on the Federal Bureau of Narcotics’ obsession with nailing Holiday on drug charges, director Lee Daniels and writer Suzan Lori-Parks ditch these revelations, instead relying on fictitious, melodramatic fluff.´

There must surely have been many viewers who, as I did, watched the film to better understand the controversy surrounding Strange Fruit, a song Holiday performed frequently, which depicts the visual horror of a lynching in such graphic poetic detail, that it has affected the thinking of a generation. Sadly, the film becomes much more invested in Holiday’s relationships—both with heroin and Federal Agent Jimmy Fletcher (Trevante Rhodes). Fletcher, a Black agent, was used as a pawn by the Federal Investigation Bureau in order to crack down on the Black community from within. Fletcher ratted on Holiday and landed her in jail for her drug use, yet Holiday supposedly welcomed him back in her social circle (and love life) without hesitation, and I was puzzled that the film made no attempt to explain this forgiveness.

´Portraying this relationship as star-crossed,´ says Keogan ´is dangerous and ahistorical rhetoric which shifts the focus of the drug war from targeting an entire community to its effect on a single cultural figure. The film is infinitely more interested in transmogrifying Holiday’s legacy in order to make her an easy-to-swallow Woke symbol than it is in unpacking the systems in place that disenfranchised her so violently.´

That´s a pretty brave piece of writing right there, in that paragraph. Questioning the methodology of film-making, the motivations of the film-maker has the effect of encouraging the reader to looking at what the Woke movement might achieve if not misappropriated.

Keogan describes the film as ´emotionally raw yet structurally weak, often (depicting) Holiday’s trauma in an uncouth and even disrespectful manner in order to feign intimacy with the subject. The structure of the film itself is disorganized and erratic—unsure whether it wants to be linear or nonlinear—at times following a distinct timeline, while jumping erratically through Holiday’s memories and performances at others. The most illuminating example of this clumsiness is in the numerous sex scenes involving Holiday and Fletcher, trying to pass discomfiting tedium as a commentary on Holiday’s lingering childhood sexual trauma. While the film attempts to avoid offense through not portraying vivid re-imaginings of the singer’s abuse, it still manages to assert a paternalism over Holiday’s (completely speculative!) sexual exploits.´

Even as she cites examples in the above paragraph of what seem to be the film´s clumsiness with the facts, and suggest such clumsiness might not be ´accidental´ she moved on in her piece to examine the film´s use of mythology, too.

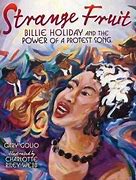

The mythology of Strange Fruit in The United States vs. Billie Holiday,´ she continues, ´is equally warped, with startling details about the song, its origins and eventual effect on Holiday’s finances all completely omitted from the biopic. Originally a poem by Bronx-born Jewish communist Abel Meeropool, the song’s royalties overwhelmingly went to the author, being the main source of revenue for his household (including sons Michael and Robert, which he adopted from executed USSR “spies” Julius and Ethel Rosenberg). Despite claims that Holiday helped set the poem to music, she received little money from one of her most popular songs. Perhaps the most lucrative way for her to claim the song was during live shows, where she routinely performed Strange Fruit, both due to audience demand and the truth to power it spoke: One of gross injustice against Black people. The film suggests that Holiday often shied away from singing the song due to fear of backlash or violence, but this is patently untrue. One scene depicts Holiday apologetically professing that she would not be performing Strange Fruit during her famous Carnegie Hall post-prison performance when she did, in fact, perform the song during this very concert.

The solitary instance that Holiday (in the guise of Andra Day, this brilliant bio-pic actress´, left) is shown actually singing Strange Fruit comes smack-dab in the middle of the film. This narrative decision leaves the audience bored while waiting for the song and unsatisfied after it is finally sung, yearning for the remainder of the film to hit anywhere near as high of a point as it reaches when Day performs. In fact, the rendition of Strange Fruit is one of the only instances Day takes centre stage and excels without hindrance from lack-luster writing or poor direction.

And despite it all, for a feature film debut, Day is incredible—a force much too powerful for the confines of this sleepy biopic. It would be remiss for her talent to go unrecognized due to the shortcomings of the creative direction of the project.´

I understand Keogan´s claims that ´a song as potently stirring and timelessly resonant as Strange Fruit´ should have been performed often and without hesitation, as that’s exactly what Holiday did throughout her unduly short yet greatly impactful career.

´It speaks to The United States vs. Billie Holiday’s neutered intentions,´ Ms. Keogan suggests, ´that it would repeatedly shy away from the very song that its subject fearlessly and frequently performed. Especially when the film ostensibly has an underlying commentary about the hesitation to implement anti-lynching legislation on a federal level, why shy away from the music that historically sparked so much outrage among racists?¨

Natalia Keogan´s is a loud and eloquent voice that made itself heard to me even through the cacophony that currently surrounds the legacy of Billie Holiday, That alone does not make her any more of a reliable narrator than others around her, but she builds solid arguments that convince me of many of the points that she makes. She, perhaps occasionally too stridently, argues her case well that the film swerves what it purports to be its main aims of demonstrating the truth, and fear thereof, about racial attitudes in America then, and perhaps still.

Her arguments, then, might suggest we (whether we are black or white) have not made as much progress as we complacently like to think since Billie first began performing Stange Fruit. However, even as the ripples roll away leaving, what we hoped might be, a clearer reflection in the water, we hear that ´coming soon, on BBC2, we bring you The Search For Billie Holiday.´

Songs, films books and documentaries have been produced and now a full blown search for Billie Holiday is to be led by the British Broadcasting Corporation. The truth might be about to be revealed.

We´ll let you know but meanwhile look out for The United States Of America Versus Billie Holiday showing across your Sky channels, directed by Lee Daniels, and written by Suzan Lori Parks, with Andra Day (totally unrelated to Billie) perfectly capturing her singing style and voice.

This article was written by Norman Warwick, owner and editor of Sidetracks & Detours, who is also a weekly contributor to Lanzarote Information. Norman is a founding member of the Joined Up Jazz Journalists who came together in 2020 to create a comprehensive coverage of jazz music and its hinterland of print and electronic media, book publishers, biographers, film-makers and recording labels, music publishers and venues that support the musicians and players. The other Joined Up Jazz Journalists include Susana Fondon, who is a colleague of Norman´s at Lanzarote Information, conducting interviews with musicians of all genres ased on or toring the island.

The other two members of JUJJ are Steve Bewick, the presenter of Hot Biscuits jazz radio programme and Gary Heywood-Everett.

You can listen to Hot Biscuits at www.fc-radio.co.uk.

And look out for another view of Billie Holiday, this tiome from BBC2, reviewed by Gary in a future issue.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!