FRANKENSTEIN´S GRANNY: The Mary Wollstonecraft statue. By Michael Higgins

FRANKENSTEIN´S GRANNY:

The Mary Wollstonecraft statue.

By Michael Higgins

Norman Warwick (editor) posed a question for me at the end of my article Last Man Reading (11 January). My article concerned the implications to modern life raised by Mary Shelley’s books, and mentions briefly her mother, the ‘Feminist’ radical authoress, moralist and political philosopher, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin.

Norman added a note with a photo of the controversial statue erected to her memory in November 2020, asking me to comment, bearing in mind the recent political issues with certain public statues. I am, Norman claims, a ‘quiet guy not noted to cause any trouble.’

After a ‘thanks a lot, Norman,’ I replied, but accepted the challenge with the promise not to stir the Make Art Great Again mobs, who may be less quiet than I.

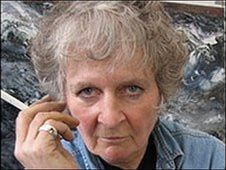

And why would any art appreciation mobs wish any harm to the statue, sculpted in silvered bronze by Maggi Hambling (left) and erected in Newington Green, London in November 2020? Well, it is very tiny for a start, – hardly a human height high, with most of that being a decorative plinth of ‘mingling’ female forms- and it depicts a harsh looking, short haired, stark full-frontal naked woman which does not remotely resemble any known portrait of Mary. Even more baffling, according to the sculptress, it is not intended to depict her at all.

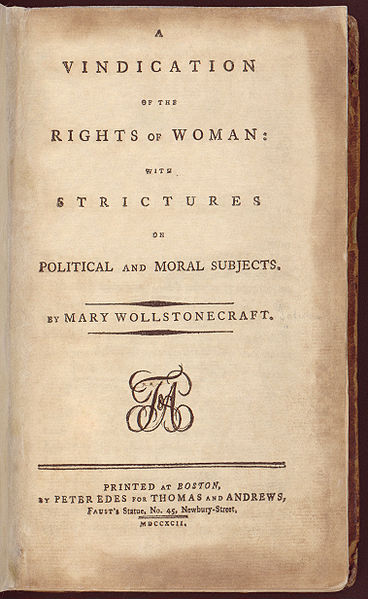

It would seem the statue was chosen by a committee more inclined to symbolism than the cosy ‘public’ appreciation of a woman tutoring children (her writings on educating girls) or arguing for a greater role for women in society than merely becoming a womb for the children of men (Vindication of the Rights of Woman). (right) Now if a man had sculpted this statue, no doubt public anger may have been more homogeneous. One sculptor’s offering was of Mary fully clothed and recognisable, but was eventually rejected.

Women critics particularly object to her brazen posing, with her infant terrible face, pert breasts and nipples and unshaven prominent, pubic mound. ‘How would a nude statue of Karl Marx look, showing all his greatness?’, they ask. Ah, says Maggi Hambling herself, her statue is meant to show the liberation of women from the clothing of restrictive society. ‘Clothing defines people and restricts people’s reaction. She’s naked and she’s everywoman.’ Eh? Not only is she not supposed to be Mary, the subject of the ten year campaign to raise the £143,000 cost to erect a memorial to Mary – a Mary on the Green- by the Mary Wollstonecraft Memorial Project, but merely an ‘everywoman’.

The real Mary Wollstonecraft married the political philosopher, William Godwin in 1797 so that their future daughter, authoress Mary Shelley, would not be born illegitimate. And Mary died a few days after giving birth to this daughter. In his supposed grief, William then wrote a scandalous memoir of his late wife’s unconventional life of illicit love affairs, illegitimate children, and attempted suicides. The poet Robert Southey claimed this insensitive expose had ‘stripped his wife bare’. Little would Mr Southey imagine that Maggi Hambling would do this more effectively over two hundred years later.

Mary comes across as a caring woman aware of the limitations of womanhood in an aristocratic, ‘primogeniture led’ society, such as Britain then was, and indeed as Revolutionary France threatened to become despite its claim to ‘Equality, Liberty and Fraternity’. Yet in 1790 she countered Edmund Burke’s attack on the French Revolution with her own ‘Vindication of the Rights of Man’, using one meaning of the word ‘man’ (mankind- human being) as against the separate word ‘man’ (male) . Thomas Paine, became more famous for his own ‘Rights of Man’ book in 1792 but Mary went one better with her own ‘Vindication of the Rights of Woman’ that year, before going to live for a while in Paris during the Jacobin led Terror. Both she and Tom Paine were for a while exiles there, barely escaping prison and execution. Yet she championed the ideals of the Revolution like so many of her contemporaries such as William Blake. Both she and Blake were consumed by the implications of the twenty-two year long war (1793-1815) with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, which raised and favoured young men for war and paternal preference, and neglected the welfare of ill educated young girls and mothers to be.

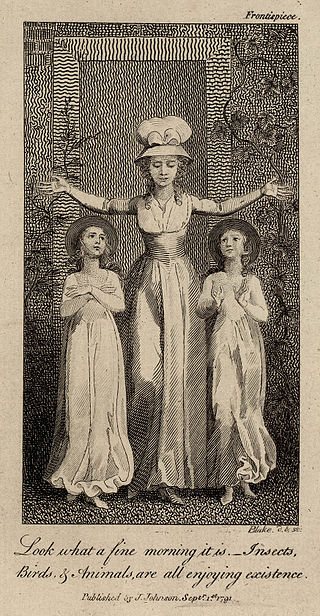

Mary was above all a woman with very maternal instincts and the trappings of femininity rather than the Feminism attribute given her in recent years. William Blake encapsulated her vulnerable spirit in his poem Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793) where as the spirit maid, Oothoon, her sighing soul gazed on the ideals of the American Revolution, was spurned by the representative conventional male piety of Theotormon, and raped by the perhaps French Revolutionary tempestuous spirit of Bromion, before being scorned by both. (Mary was very unlucky in love and affection). Now you might ask that if Blake were a sculptor instead of an engraver, would he have sculpted this vision of poor Mary? I doubt it. Blake’s engravings glorified in the diaphanous high- waisted flowing Georgian dress. But Blake did illustrate her Vindication of the Rights of Woman, with homely pictures of her (right) that would to my mind at least make a real Mary out of a block of stone.

All biographers should aim to depict their subject as real life people and write a life that is true to what they wanted to be and what perhaps they actually became. The same should attain to graphic art and sculpture. Maggi Hambling may have aimed her tiny infant of a statue at the Feminist, Idealistic, Modernist art gallery mind, and as an antidote to the oversized public statues of famous men, but she should also have had regard also to Mary and her public, the great audience who when passing the statue ought to be given something relevant of her life and legend. This statue instead screams Maggi and not Mary.

On the plinth are the words ‘For Mary Wollstonecraft’, omitting the married name she cherished: Godwin. For years she sought the domestic comforts of marriage with the father of her first child, but was eventually abandoned. In William Godwin, the father of her second, she thought she had found a true meeting of mind and spirit. It is a pity then that witty critics of the statue have re-named it ‘Frankenstein’s Granny’ with reference to her daughter’s fame as the creator of that gothic tale of marred beauty, reckless ambition, unrequited love and spurned affection. More up to date wits have named the statue ‘Barbie on a Rock’, but for me she is no Barbie, rather that vapid nonentity called ‘Everywoman’, which Mary certainly was not. Mary is quoted on the plinth as saying: ‘I do not wish women to have power over men but over themselves.’ Alas for Mary, she reckoned without the power of a Sculptress to strip her of her of her attributes and legend.

That legend is however still haunting Newington Green, in the Unitarian chapel or meeting house there which she attended whilst running her girl’s school. With a facade of a nineteenth century appearance, bearing a panel, in scrolled architrave, on which is enscribed, ´´erected A.D. 1708, enlarged A.D. 1860. The Unitarian Church is known for its connection to the English dissenting movement of the late 18th century. One of the movements notable figures Dr Richard Price began preaching at the church after moving to the area in 1758. During his time at Newington Green he hosted prominent figures of the American Revolution including John Adams, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. As a preacher at the Unitarian Church Dr Price one of his congregants was Mary Wollstonecraft. She moved her fledgling school for girls to the area in 1784. Her links with the dissenting community helped develop her ideas for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, for which she earned her reputation as a pioneer of feminism.

by Joan Littlewood

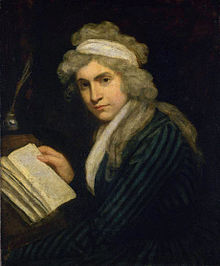

A bust of Mary by Jenny Littlewood, based on the portrait of her painted by John Opie, was installed there a few weeks after Hambling’s statue was unveiled. For those wishing to see the real Mary, this is for you. (right)

John Opie 1761 –1807) was a Cornish historical and portrait painter. He painted many great men and women of his day, including members of the British Royal Family, and others who were most notable in the artistic and literary professions. His works included presentations of Mary Wollstencraft shown below.

On the left we see Opie´s 1791 portrait and on the right, below, a portrait taken some seven or eight years later.

Dr. Jennie Littlewood created her first public sculpture for a competition run by the Tate gallery in 1970, and has created several interesting works as show in our photograph. She says of her current status that she has been a leader and a volunteer for my local community for many years, establishing a ‘green corridor’ by strategic developments in biodiversity (planting over 60 native trees, promoting planting and ponds, creating gardening clubs and wildlife forum, helping to ensure the first Passivhaus community centre built in the UK). I support the Islington Sustainability Forum.´ Jenny was also the Chair of the Newington Green Action Group until 2015 and is a supporter of New Unity.

Maggi Hambling CBE is a British artist. Though principally a painter her best-known public works are the sculptures A Conversation with Oscar Wilde and the 4-metre-high steel Scallop on Aldeburgh beach as well as the more recent A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft in London, All three works have attracted controversy.

As for Maggi Hambling’s statue of Mary, which she admits is NOT Mary, perhaps it could surreptitiously be re-named ‘Everywoman’ and moved where ‘every-person’ statues rest. Oops I didn’t mean to say that. Keep it where it is please. Put a Tee shirt over it as some counter-Feminists have done if you must abet public decency, but leave the rest alone. It is after all a work of art in its own right.

Whew! Glad that’s over.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!