THERE IS JAZZ LEGEND PROVEN

Norman Warwick learns from others that

THERE IS JAZZ LEGEND PROVEN

and there is jazz with a promise to keep

It seems to me that those who are ordained as ¨Jazz Legend´ have often been so titled by a less than unanimous vote. Maybe my perspective of all this is skewed by lack of any authoritative knowledge of the mysteries of jazz, and also, slightly perhaps by my stupidly proud boast that I was not born to follow.Whatever the reason it is definitely a truism of my life that if one of my learned jazz friends calls Ella Fitzgerald a legend of jazz there will be others who will name twerty female jazz singers they feel were more influential. Steve Bewick, our jazz correspondent loves his sketches from Spain, and so he might deem Miles Davis to be a jazz legend but there might have been many in the Jazz On Sunday audience who would disagree with him. Nevertheless, Bewick is a broadcaster, poet, artist and author who feeds me reliable information from Jazz Junction and who introduced me to the works of Jenny Bray, featured in our recent PASS IT ON 63 Sunday Supplement. I love Jenny´s approach to her style of jazz music and that there is so much storytelling in her jazz that reminds me of my favourite country, Americana and folk musicians like Joni Mitchell who´s fans must be enjoying the newly packaged and re-launched sounds that was highlighted recently, and is available in our easy to negotiate archives of around 1,200 free to read arts related items

If I was to speak about those who are legends of jazz, and those who might one day be seen as legends of jazz, as Geoffrey Himes, the self styled Old Curmudgeon, has done recently when writing in Paste On Line, my lack of jazz chops might lead me into terrible trouble.

I recognise that to become a legend, a musician first (?) create legacy. Because I have all her albums and can see improvements and changes of direction and wider hinterland on all of them I would say with some confidence that Karla Harris is already building a legacy, especially, when working with the Joe Alterman Trio, I would say that Karla Harris will definitely create a long-standing legacy and on that score, at least, become a legend of Jazz. Is she a Besse Smith or Billie Holiday and will she ever live those legendary life stories? Almost certainly not. However, she has been my favourite jazz artist since I first heard her music, and to me it is the music that should be judged.

Who do I think is a legend of Jazz? For my type of jazz it would Nat King Cole or Oscar Peterson. However, other names fell out in conversation when Gewoffrey Himes recently wrote on this subject.

They’re not as well known as Brad Mehldau or Jason Moran, said Geoffrey in the opening top of his piece, but Myra Melford and Gonzalo Rubalcaba (see our cover) are two of the most impactful pianists working today. Neither of them show off with fast and flashy solos, instead using instinctive note choices and well placed pauses to create a strong force field of feeling. Melford is the co-leader, with the virtuosic drummer Allison Miller, of the Lux Quartet, whose debut album is Tomorrowland. The new band’s name is taken from the Latin word for sunlight, and a bright optimism seems to shine through these unhurried, uncluttered arrangements. This encourages the kind of seductive melodic themes that might lapse into sentimentality if not for the tough-minded bottom provided by Miller and bassist Scott Colley.

Each woman writes three of the eight tunes, with Colley and saxophonist Dayna Stephens contributing one apiece. Melford often plays quick splashes of notes with punctuating pauses as Miller’s rumbling drums push and pull at the time. The beat isn’t always explicit, but when the four instruments reconnect to that throb after wandering around, the effect is thrilling, because it reminds us that the pulse was there all along. The music stretches quite a bit, but it never breaks and always snaps back. This allows us to trust the musicians as they digress far and wide.

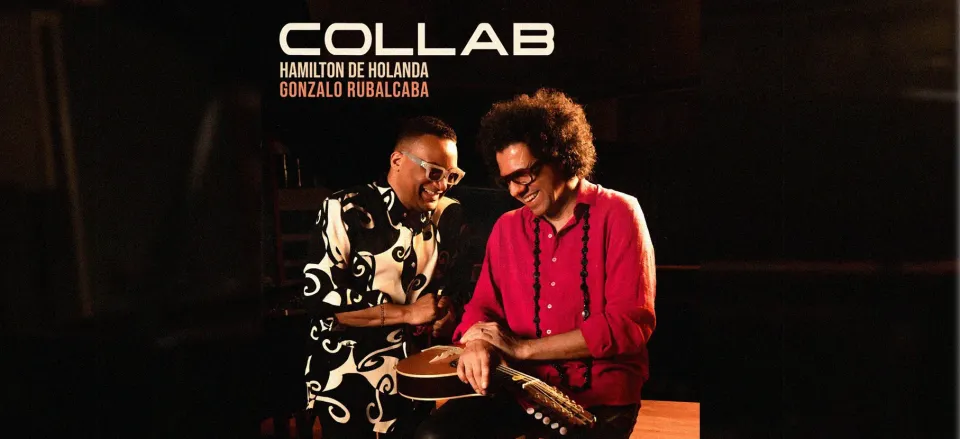

Another new album, Collab, (left) is named for the mostly unaccompanied collaboration between Rubalcaba and Hamilton De Holanda. The latter is the David Grisman of Brazil, someone who has not only mastered the mandolin but also expanded its possibilities. Working without horns or a rhythm section, the two acoustic instruments dance around each other in a conversation that can be as ebullient, agitated or melancholy as each piece requires.

What’s most impressive is how quickly they create a mood without words and then tell a story within that framework. Each man contributes three original compositions, supplemented by standards from Brazil and the U.S. The Brazilian harmonica whiz Gabriel Grossi joins the duo on Stevie Wonder’s “Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing,” and Brazil’s João Bosco sings on his own tune, “Incompatibilidade de Gênios.” That translates from the Portuguese as “The Incompatibility of Geniuses,” but these two musical masterminds communicate telepathically—not only with each other but also with us the listeners.

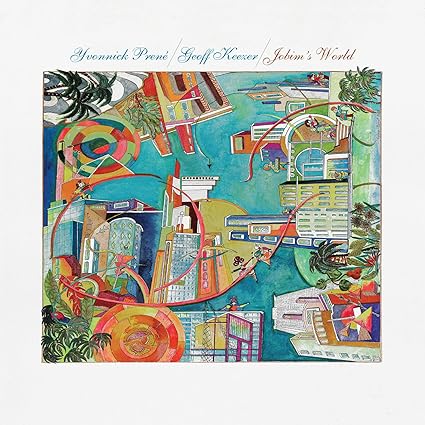

The harmonica and Brazilian music also collide on yet another new album, Jobim’s World, (see right, below) from another unaccompanied duo, this time featuring American pianist Geoffrey Keezer and French harmonica player Yvonnick Prené. Antonio Carlos Jobim, the Brazilian Ellington who wrote dozens of jazz standards before dying in 1994, composed five of the nine pieces. His earworm melodies and samba syncopation allow Keezer and Prené to playfully twist and turn the originals without ever losing their essential appeal. The duo often functions as a quartet, with Keezer’s left hand as the bass ‘n’ drums, his right hand as the guitar and Prené’s chromatic harmonica as the sax.

Keezer has one more new album out, Live at Birdland, recorded with his trio at the famed Manhattan venue. This disc is dedicated to the enduring compositions of Chick Corea and Wayne Shorter, who both recently died in 2021 and 2023 respectively. Keezer’s bassist John Patitucci spent long stretches in the bands of both Corea and Shorter, lending a personal connection to this tribute record. Clarence Penn, drummer of choice for Dave Douglas and Maria Schneider, completes the trio.

Some of these tunes, such as Corea’s “Imp’s Welcome” and Shorter’s “Joy Ryder” were originally recorded on electric keyboards. In transferring them to acoustic piano, Keezer demonstrates that the pieces have more than enough musical substance to succeed without buzzing circuitry. Keezer has the chops to handle the obvious aspects of these tunes and the imagination to tease out new implications. Best of all, he follows Shorter’s example in giving his bandmates the room to do the same.

Matt Mitchell, not to be confused with this magazine’s music editor, also leads his own democratic trio on the new album, Zealous Angles, giving bassist Chris Tordini and drummer Dan Weiss plenty of opportunities to put their own stamp on the music. Mitchell takes Keezer one step further: He doesn’t merely translate electric keyboard songs to acoustic piano; he translates the electric keyboard vocabulary to the ivories.

Mitchell plays the microchip patterns of synthesizers and samplers on the piano, layering the cyclical loops and repetitions one over the other, as a machine might but with intuitive dynamics and displacements. It’s as if he’s arguing that the rhythmic innovations of the 21st century’s technology can be humanized for jazz improvisation. In every era, jazz has had to adapt the rhythmic foundation of contemporary popular music to the needs of sophisticated improvisers, and Mitchell is doing just that for our era. Tordini and Weiss reinforce his efforts at every turn.

Clarence Penn is also the drummer on Canadian pianist Andy Milne’s new album, Time Will Tell, Four of the tracks feature the unaccompanied piano trio of Milne, Penn and bassist John Hébert, and six feature Milne solo or with the trio and/or saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock and/or koto player Yoko Reikana Kimura. The koto is crucial, because the Japanese, horizontal, table-harp connects with Milne’s long-term interest in Zen Buddhism. Kimura’s patient, pointillist attack on her instrument encourages Milne to approach the piano the same way.

This is most obvious on “Lost & Found,” one of seven Milne originals on the album. This yearning ballad came out the adopted pianist’s search for his birth mother during the pandemic. Both the unfinished business of not knowing and the closure of finally meeting her are reflected in this powerful tune. This thoughtful fusion of North American jazz and Japanese classical music can also be heard on several other tracks. It works only because Milne’s preparation echoed his motives, which were personal rather than commercial.

The prime source for this article was published in Paste On Line and written by the Geoffrey Himes. We share this with our readers with the confidence that you will seriously consider becoming a subscriber to Paste and similar media sites we occasionally refer to. They have knowledge and resources we don´t, and as a not for profit blog we cannot afford.

Authors and Titles have been attributed in our text wherever possible

Images employed have been taken from on line sites only where categorised as images free to use.

For a more comprehensive detail of our attribution policy see our for reference only post on 7th April 2023 entitled Aspirations And Attributions.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!