FROM STILL LIFE TO BRIEF ENCOUNTER

Norman Warwick moves from

FROM STILL LIFE TO BRIEF ENCOUNTER

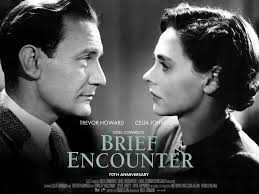

Sidetracks And Detours recently shared with you a review of a stage production of Brief Encounters submitted by Steve Griffiths to our friends at all across the arts, who positively answered our call to PASS IT ON.

It was a really informative piece but although I was familiar with the film, I couldn´t recall whether it has been drawn from a book. If so, I feared I was gonna need a bigger bookshelf

we´re gonna need a bigger theatre

were gonna need a bigger cinema

WE´RE GONNA NEED A BIGGER BOOKSHELF

It turns out it was drawn from a film.

Still Life is a short play in five scenes by Noël Coward, one of ten plays that make up Tonight at 8.30, a cycle written to be performed across three evenings. One-act plays were unfashionable in the 1920s and 30s, but Coward was fond of the genre and conceived the idea of a set of short pieces to be played across several evenings. The actress most closely associated with him was Gertrude Lawrence, and he wrote the plays as vehicles for them both.

The play portrays the chance meeting, subsequent love affair, and eventual parting of a married woman and a physician. The sadness of their serious and secretive affair is contrasted throughout the play with the boisterous, uncomplicated relationship of a second couple. Still Life differs from most of the plays in the cycle by having an unhappy ending.

The play was first produced in London in May 1936 and was staged in New York in October of that year. It has been revived frequently and has been adapted for television and radio and, as Brief Encounter, for the cinema.

The play’s five scenes are set across the span of a year, from April to March. It charts the love affair between Laura Jesson, a housewife, and Alec Harvey, a married physician. The location is the refreshment room of “Milford Junction” railway station.

In the first scene Myrtle, who runs the station buffet, rebuffs the attempts of Albert, the ticket-inspector, to flirt with her. Laura is waiting for her train home after shopping. She is in pain from a piece of grit that has been blown into her eye. Alec introduces himself as a doctor and quickly removes it for her. She thanks him and goes to catch her train.

Three months later Alec and Laura are once more in the refreshment room. It becomes clear that after their first meeting they encountered each other a second time by chance and have enjoyed each other’s company to the extent of arranging to lunch together and go to the cinema. There have been several such meetings. Laura is beginning to wonder about the propriety of meeting him so often, but Alec reminds her that he too is married, with children and other responsibilities.

In the third scene, set in October, Albert and Myrtle continue their slightly combative flirtation. Alec and Laura come in, and over coffee they admit that they are in love with each other. They are both determined not to upset their happy marriages, but will meet secretly. They make arrangements to meet at the flat of a friend of Alec.

By December they are both agonised by guilt and agree that their affair must stop. Alec tells Laura that he has been offered an attractive medical post in South Africa and will accept it unless she asks him not to.

The fifth and final scene is set in March. Albert seems to be making progress with Myrtle. Alec and Laura enter. He is leaving to take up his new post in South Africa, and she has come to see him off. They are prevented from having the passionate farewell they both yearn for when Dolly, a talkative friend of hers intrudes into their last moments together, and their final goodbye is cruelly limited to a formal handshake. He leaves, and Laura remains, while Dolly talks on. Suddenly, as the sound of the approaching express train is heard, Laura suddenly rushes out to the platform. She returns “looking very white and shaky”. Dolly persuades Myrtle to pour some brandy for Laura, who sips it. The sound of their train is heard, and Dolly gathers up her parcels as the curtain falls.

Coward later said of the play, “Still Life was the most mature play of the whole series. … It is well written, economical and well constructed: the characters, I think, are true, and I can say now, reading it with detachment after so many years, that I am proud to have written it.” John Lahr, in his 1982 book on Coward’s plays, disagreed: “when he wrote himself into the role of an ardent heterosexual lover … the characterisation is wooden. The master of the comic throw-away becomes too loquacious when he gets serious, and his fine words ring false.” At the first production, critical opinion agreed with Coward. The Times called it “a serious and sympathetic study of humdrum people suddenly trapped by love” and strongly praised Coward both for the play and his performance. In a 1989 study of Coward, Milton Levin wrote:

“The theme that basic decency wins out is hardly a novel idea. Yet, both characters and their situation are endowed with a weight and substance that are rare for Coward. In large part the solidity of the refreshment room gives such reality to the lovers, but they are also very carefully observed individuals. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the whole play is given life and its fullest pathos by the restrained dialogue, in which little is said but much implied.”

Levin suggests that when Laura rushes onto the platform as the express train thunders by she has suicide in mind; this possibility is made explicit in the film adaptation of the play, Brief Encounter..

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!