UNDER MILK WOOD began Norman Warwick´s love affair with words

Norman Warwick held enthralled by the voices of

UNDER MILK WOOD

Under Milk Wood is a 1954 radio drama by Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, commissioned by the BBC and later adapted for the stage. A film version, Under Milk Wood directed by Andrew Sinclair, was released in 1972, and another adaptation of the play, directed by Pip Broughton, was staged for television for the 60th anniversary in 2014.

An omniscient narrator invites the audience to listen to the dreams and innermost thoughts of the inhabitants of the fictional small Welsh fishing village, Llareggub.

They include Mrs. Ogmore-Pritchard, relentlessly nagging her two dead husbands; Captain Cat, reliving his seafaring times; the two Mrs. Dai Breads; Organ Morgan, obsessed with his music; and Polly Garter, pining for her dead lover. Later, the town awakens and, aware now of how their feelings affect whatever they do, we watch them go about their daily business.

The Coach & Horses in Tenby, where Thomas is reputed to have been so drunk that he left his manuscript to Under Milk Wood on a stool

In 1931, the 17-year-old Thomas created a piece for the Swansea Grammar School magazine which included a conversation of Milk Wood stylings, between Mussolini and Wife, similar to those between Mrs. Ogmore-Pritchard and her two husbands that would later be found in Under Milk Wood. In 1933, Thomas talked at length with his mentor and friend, Bert Trick, about creating a play about a Welsh town:

He read it to Nell and me in our bungalow at Caswell around the old Dover stove, with the paraffin lamps lit at night … the story was then called Llareggub, which was a mythical village in South Wales, a typical village, with terraced houses with one ty bach to about five cottages and the various characters coming out and emptying the slops and exchanging greetings and so on; that was the germ of the idea which … developed into Under Milk Wood.

In March 1938, Thomas suggested that a group of Welsh writers should prepare a verse-report of their “own particular town, village, or district.” A few months later, in May 1938, the Thomas family moved to Laugharne, a small town on the estuary of the river Tâf. They lived there intermittently for just under two years until July 1941, and did not return to live there until 1949. The author Richard Hughes, who lived in Laugharne, has recalled that Thomas spoke with him in 1939 about writing a play about Laugharne in which the villagers would play themselves, an idea pioneered on the radio by Cornish villagers in the 1930s. Four years later, in 1943, Thomas met again with Hughes, and this time outlined a play about a Welsh village certified as mad by government inspectors.

Hughes was of the view that when Thomas “came to write Under Milk Wood, he didn’t use actual Laugharne characters.” Nevertheless, there are some elements of Laugharne that are discernible in the play. A girl named Rosie Probert, age 14, was living in Horsepool Road in Laugharne at the 1921 census, though there is no-one of that name in Laugharne in the 1939 War Register, nor anyone named Rosie. Both Laugharne and Llareggub have a castle and, like Laugharne, Llareggub is on an estuary (“boat-bobbing river and sea”), with cockles, cocklers and Cockle Row. Laugharne also provides the clock tower of Myfanwy Price’s dreams,[13] as well as Salt House Farm which may have inspired the name of Llareggub’s Salt Lake Farm. Llareggub’s Butcher Beynon almost certainly draws on butcher and publican Carl Eynon, though he was not in Laugharne but in nearby St Clears.

In September 1944, the Thomas family moved to a bungalow called Majoda on the cliffs outside New Quay, Cardiganshire (Ceredigion), and left in July the following year. Thomas had previously visited New Quay whilst living in nearby Talsarn in 1942–1943, and had an aunt and cousins living there. He had written a New Quay pub poem, Sooner than you can water milk, in 1943, which has several words and ideas that would later re-appear in Under Milk Wood.

Thomas’ wife, Caitlin, has described the year at Majoda as “one of the most important creative periods of his life…New Quay was just exactly his kind of background, with the ocean in front of him…and a pub where he felt at home in the evenings.” Thomas’ biographers have also viewed the year in New Quay as one of the most productive periods of his adult life. His time there, recalled Constantine FitzGibbon, his first biographer, was “a second flowering, a period of fertility that recalls the earliest days…[with a] great outpouring of poems”, as well as a good deal of other material.[22] Biographer Paul Ferris agreed: “On the grounds of output, the bungalow deserves a plaque of its own.”

Some of those who knew him well, including Constantine FitzGibbon, have said that he began writing Under Milk Wood in New Quay.[24] The play’s first producer, Douglas Cleverdon, concurred, noting that Thomas “wrote the first half within a few months; then his inspiration seemed to fail him when he left New Quay.”[25] One of Thomas’ closest friends and confidante, Ivy Williams of Brown’s Hotel, Laugharne, has said “Of course, it wasn’t really written in Laugharne at all. It was written in New Quay, most of it.”[26]

The writer and puppeteer, Walter Wilkinson, visited New Quay in 1947, and his essay on the town captures its character and atmosphere as Thomas would have found it two years earlier. Photos of New Quay in Thomas’ day, as well as a 1959 television programme about the town, can be found here.

There were many milestones on the road to Llareggub, and these have been detailed by Professor Walford Davies in his Introduction to the definitive edition of Under Milk Wood. The most important of these was Quite Early One Morning, Thomas’ description of a walk around New Quay, broadcast by the BBC in 1945, and described by Davies as a “veritable storehouse of phrases, rhythms and details later resurrected or modified for Under Milk Wood.” One striking example from the broadcast is:

Open the curtains, light the fire, what are servants for?

I am Mrs. Ogmore Pritchard and I want another snooze.

Dust the china, feed the canary, sweep the drawing-room floor;

And before you let the sun in, mind he wipes his shoes.

Mrs Ogmore Davies and Mrs Pritchard-Jones[ both lived on Church Street in New Quay.] Mrs Pritchard-Jones was constantly cleaning, recalled one of her neighbours, “a real matron-type, very strait-laced, house-proud, ran the house like a hospital ward.” In her book on New Quay, Mrs Pritchard-Jones’ daughter notes that her mother had been a Queen’s Nurse before her marriage and afterwards “devoted much of her time to cleaning and dusting our home…sliding a small mat under our feet so we would not bring in any dirt from the road.”

Jack Lloyd, a New Quay postman and the Town Crier, also lived on Church Street. He provided the character of Llareggub’s postman Willy Nilly, whose practice of opening letters, and spreading the news, reflects Lloyd’s role as Town Crier, as Thomas himself noted on a work sheet for the play: “Nobody minds him opening the letters and acting as [a] kind of town-crier. How else could they know the news?” It is this note, together with our knowledge that Thomas knew Jack Lloyd that establish the link between Willy Nilly and Lloyd.

There were also other New Quay residents in Under Milk Wood. Dai Fred Davies the donkeyman on board the fishing vessel, the Alpha, appears in the play as Tom-Fred the donkeyman. Local builder, Dan Cherry Jones, appears as Cherry Owen] and as Cherry Jones in Thomas’ sketch of Llareggub.] And the time-obsessed, “thin-vowelled laird”, as Thomas described him, New Quay’s reclusive English aristocrat, Alastair Hugh Graham, lover of fish, fishing and cooking, and author of Twenty Different Ways of Cooking New Quay Mackerel, is considered to be the inspiration for “Lord Cut-Glass…that lordly fish-head nibbler…in his fish-slimy kitchen…[who] scampers from clock to clock…”

Other names and features from New Quay in the play include Maesgwyn farm, the Sailor’s Home Arms, the river Dewi, the quarry, the harbour, Manchester House, the hill of windows and the Downs.] The Fourth Drowned’s line “Buttermilk and whippets” also comes from New Quay, as does the stopped clock in the bar of the Sailors’ Arms.

Walford Davies has concluded that New Quay “was crucial in supplementing the gallery of characters Thomas had to hand for writing Under Milk Wood.” FitzGibbon had come to a similar conclusion many years earlier, noting that Llareggub “resembles New Quay more closely [than Laugharne] and many of the characters derive from that seaside village in Cardiganshire…” John Ackerman has also suggested that the story of the drowned village and graveyard of Llanina, that lay in the sea below Majoda, “is the literal truth that inspired the imaginative and poetic truth” of Under Milk Wood. Another part of that literal truth were the sixty acres of cliff between New Quay and Majoda, including Maesgwyn farm, that collapsed into the sea in the early 1940s.

On his return to Laugharne, Thomas worked in a desultory fashion on Under Milk Wood throughout the summer. He gave readings of the play in Porthcawl and Tenby, before travelling to London to catch his plane to New York for another tour, including three readings of Under Milk Wood. He stayed with the comedian Harry Locke, and worked on the play, re-writing parts of the first half, and writing Eli Jenkins’ sunset poem and Waldo’s chimney sweep song for the second half.Locke noticed that Thomas was very chesty, with “terrible” coughing fits that made him go purple in the face.

On 15 October 1953, Thomas delivered another draft of the play to the BBC, a draft that his producer, Douglas Cleverdon, described as being in “an extremely disordered state…it was clearly not in its final form.”[83] On his arrival in New York on 20 October 1953, Thomas added a further thirty-eight lines to the second half, for the two performances on 24 and 25 October.

Thomas had been met at the airport by Liz Reitell, who was shocked at his appearance: “He was very ill when he got here.” Thomas’ agent John Brinnin, deeply in debt and desperate for money, also knew Thomas was very ill, but did not cancel or curtail his programme, a punishing schedule of four rehearsals and two performances of Under Milk Wood in just five days, as well as two sessions of revising the play. After the first performance on 24 October, Thomas was close to collapse, standing in his dressing room, clinging to the back of a chair. The play, he said, “has taken the life out of me for now.” At the next performance, the actors realised that Thomas was very ill and had lost his voice: “He was desperately ill…we didn’t think that he would be able to do the last performance because he was so ill … Dylan literally couldn’t speak he was so ill…still my greatest memory of it is that he had no voice.” After a cortisone injection, he recovered sufficiently to go on stage. The play’s cast noticed Thomas’ worsening illness during the first three rehearsals, during one of which he collapsed. Brinnin was at the fourth and was shocked by Thomas’ appearance: “I could barely stop myself from gasping aloud. His face was lime-white, his lips loose and twisted, his eyes dulled, gelid, and sunk in his head.”

Then through the following week, Thomas continued to work on the script for the version that was to appear in Mademoiselle, and for the performance in Chicago on 13 November. However, he collapsed in the early hours of 5 November and died in hospital on 9 November 1953.

The inspiration for the play has generated intense debate. Thomas himself declared on two occasions that his play was based on Laugharne, but this has not gone unquestioned. Llansteffan, Ferryside and particularly New Quay also have their claims. An examination of these respective claims was published in 2004.] Surprisingly little scholarship has been devoted to Thomas and Laugharne, and about the town’s influence on the writing of Under Milk Wood.] Thomas’ four years at the Boat House were amongst his least productive, and he was away for much of the time. As his daughter, Aeronwy, has recalled, “he sought any pretext to escape.”

Douglas Cleverdon has suggested that the topography of Llareggub ” is based not so much on Laugharne, which lies on the mouth of an estuary, but rather on New Quay, a seaside town…with a steep street running down to the harbour.” The various topographical references in the play to the top of the town, and to its ‘top and sea-end’ are also suggestive of New Quay, as are Llareggub’s terraced streets and hill of windows. The play is even true to the minor topographical details of New Quay. For example, Llareggub’s lazy fishermen walk uphill from the harbour to the Sailors’ Arms.

Thomas drew a sketch map of the fictional town, which is now held by the National Library of Wales and can be viewed online. The Dylan Thomas scholar, James Davies, has written that “Thomas’s drawing of Llareggub is… based on New Quay” and there has been very little disagreement, if any, with this view. An examination of the sketch has revealed some interesting features: Thomas uses the name of an actual New Quay resident, Dan Cherry Jones, for one of the people living in Cockle Street. The Rev. Eli Jenkins is not in the sketch, however, and there are also three characters in the sketch who do not appear in the draft of the play given by Thomas to the BBC in October 1950.

Thomas also seems to have drawn on New Quay in developing Llareggub’s profile as an ocean-going, schooner and harbour town, as he once described it. Captain Cat lives in Schooner House. He and his sailors have sailed the clippered seas, as First Voice puts it. They have been to San Francisco, Nantucket and more, bringing back coconuts and parrots for their families. The Rev. Eli Jenkins’ White Book of Llareggub has a chapter on shipping and another on industry, all of which reflect New Quay’s history of both producing master mariners and building ocean-going ships, including schooners. In his 1947 visit to New Quay, Walter Wilkinson noted that the town “abounds” in sea captains The following year, another writer visiting New Quay noted that there were “dozens of lads who knew intimately the life and ways of all the great maritime cities of the world.”

Llareggub’s occupational profile as a town of seafarers, fishermen, cockle gatherers and farmers has also been examined through an analysis of the returns in the 1939 War Register for New Quay, Laugharne, Ferryside and Llansteffan. This analysis also draws upon census returns and the Welsh Merchant Mariners Index. It shows that New Quay and Ferryside provide by far the best fit with Llareggub’s occupational profile.

Thomas is reported to have commented that Under Milk Wood was developed in response to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, as a way of reasserting the evidence of beauty in the world. It is also thought that the play was a response by Thomas both to the Nazi concentration camps, and to the internment camps that had been created around Britain during World War II.

The fictional name Llareggub was derived by reversing the phrase “bugger all“. In early published editions of the play, it was often rendered (contrary to Thomas’s wishes) as Llaregyb or similar. It is pronounced [ɬaˈrɛɡɪb]. The name bears some resemblance to many actual Welsh place names, which often begin with Llan, meaning church or, more correctly, sanctified enclosure, although a double g is not used in written Welsh.

The name Llareggub was first used by Thomas in two short stories published in 1936. They were The Orchards] (“This was a story more terrible than the stories of the reverend madmen in the Black Book of Llareggub.”) and The Burning Baby (“Death took hold of his sister’s legs as she walked through the calf-high heather up the hill… She was to him as ugly as the sowfaced woman Llareggub who had taught him the terrors of the flesh.”)

Thomas’ first known use of the name Llareggub in relation to Under Milk Wood was at a recitation of an early version of the play at a party in London in 1945.[110]

Thomas had also referred to the play as The Village of the Mad or The Town that was Mad. By the summer of 1951, he was calling the play Llareggub Hill but by October 1951, when the play was sent to Botteghe Oscure, its title had become Llareggub. A piece for Radio Perhaps. By the summer of 1952, the title was changed to Under Milk Wood because John Brinnin thought Llareggub Hill would be too thick and forbidding to attract American audiences.

In the play, the Rev Eli Jenkins writes a poem that describes Llareggub Hill and its “mystic tumulus“. This was based on a lyrical description of Twmbarlwm‘s “mystic tumulus” in Monmouthshire that Thomas imitated from Arthur Machen‘s autobiography Far Off Things (1922).

The town’s name is the inspiration for the country of Llamedos (sod ’em all) in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novel Soul Music. In this setting, Llamedos is a parody of Wales.

The play opens at night, when the citizens of Llareggub are asleep. The narrator (First Voice/Second Voice) informs the audience that they are witnessing the townspeople’s dreams.

Captain Cat, the blind sea captain, is tormented in his dreams by his drowned shipmates, who long to live again and enjoy the pleasures of the world. Mog Edwards and Myfanwy Price dream of each other; Mr. Waldo dreams of his childhood and his failed marriages; Mrs. Ogmore-Pritchard dreams of her deceased husbands. Almost all of the characters in the play are introduced as the audience witnesses a moment of their dreams.

Morning begins. The voice of a guide introduces the town, discussing the facts of Llareggub. The Reverend Eli Jenkins delivers a morning sermon on his love for the village. Lily Smalls wakes and bemoans her pitiful existence. Mr. and Mrs. Pugh observe their neighbours; the characters introduce themselves as they act in their morning. Mrs. Cherry Owen merrily rehashes her husband’s drunken antics. Butcher Beynon teases his wife during breakfast. Captain Cat watches as Willy Nilly the postman goes about his morning rounds, delivering to Mrs. Ogmore-Pritchard, Mrs. Pugh, Mog Edwards and Mr. Waldo.

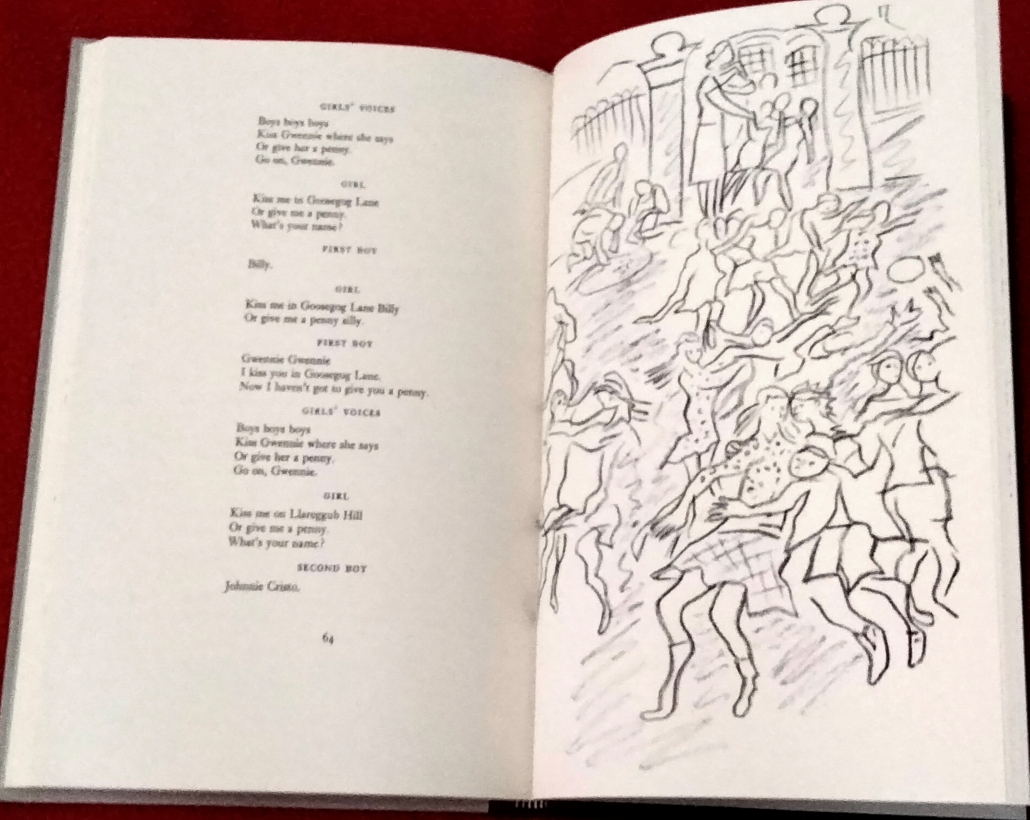

At Mrs. Organ-Morgan’s general shop, women gossip about the townspeople. Willy Nilly and his wife steam open a love letter from Mog Edwards to Myfanwy Price; he expresses fear that he may be in the poor house if his business does not improve. Mrs. Dai Bread Two swindles Mrs. Dai Bread One with a bogus fortune in her crystal ball. Polly Garter scrubs floors and sings about her past paramours. Children play in the schoolyard; Gwennie urges the boys to “kiss her where she says or give her a penny.” Gossamer Beynon and Sinbad Sailors privately desire each other.

During dinner, Mr. Pugh imagines poisoning Mrs. Pugh. Mrs. Organ-Morgan shares the day’s gossip with her husband, but his only interest is the organ. The audience sees a glimpse of Lord Cut-Glass’s insanity in his “kitchen full of time”. Captain Cat dreams of his lost lover, Rosie Probert, but weeps as he remembers that she will not be with him again. Nogood Boyo fishes in the bay, dreaming of Mrs. Dai Bread Two and geishas.

On Llareggub Hill, Mae Rose Cottage spends a lazy afternoon wishing for love. Reverend Jenkins works on the White Book of Llareggub, which is a history of the entire town and its citizens. On the farm, Utah Watkins struggles with his cattle, aided by Bessie Bighead. As Mrs. Ogmore-Pritchard falls asleep, her husbands return to her. Mae Rose Cottage swears that she will sin until she explodes.

As night begins, Reverend Jenkins recites another poem. Cherry Owen heads to the Sailor’s Arms, where Sinbad still longs for Gossamer Beynon. The town prepares for the evening, to sleep or otherwise. Mr. Waldo sings drunkenly at the Sailors Arms. Captain Cat sees his drowned shipmates—and Rosie—as he begins to sleep. Organ-Morgan mistakes Cherry Owen for Johann Sebastian Bach on his way to the chapel. Mog and Myfanwy write to each other before sleeping. Mr. Waldo meets Polly Garter in a forest. Night begins and the citizens of Llareggub return to their dreams again.

The first publication of Under Milk Wood, a shortened version of the first half of the play, appeared in Botteghe Oscure in April 1952. Two years later, in February 1954, both The Observer newspaper and Mademoiselle magazine published abridged versions. The first publications of the complete play were also in 1954: J. M. Dent in London in March and New Directions in America in April.

An Acting Edition of the play was published by Dent in 1958. The Definitive Edition, with one Voice, came out in 1995, edited by Walford Davies and Ralph Maud. A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook for free use went online in November 2006, produced by Colin Choat.

The first translation was published in November 1954 by Drei Brücken Verlag in Germany, as Unter dem Milchwald, translated by Erich Fried. A few months later, in January 1955, the play appeared in the French journal Les Lettres Nouvelles as Le Bois de Lait, translated by Roger Giroux, with two further instalments in February and March.

Over the next three years, Under Milk Wood was published in Dutch, Polish, Danish, Estonian, Norwegian, Finnish, Swedish, Japanese and Italian. It’s estimated that it has now been translated into over thirty languages, including Welsh with a translation by T. James Jones, (Jim Parc Nest), published in 1968 as Dan Y Wenallt.

The original manuscript of the play was lost by Thomas in a London pub, a few weeks before his death in 1953. The alleged gift of the manuscript, to BBC producer Douglas Cleverdon, formed the subject of litigation in Thomas v Times Book Co (1966) which is a leading case on the meaning of gift in English property law.

The play had its first reading on stage on 14 May 1953, in New York City, at The Poetry Center at the 92nd Street Y. Thomas himself read the parts of the First Voice and the Reverend Eli Jenkins. Almost as an afterthought, the performance was recorded on a single-microphone tape recording (the microphone was laid at front center on the stage floor) and later issued by the Caedmon company. It is the only known recorded performance of Under Milk Wood with Thomas as a part of the cast. A studio recording, planned for 1954, was precluded by Thomas’s death in November 1953.

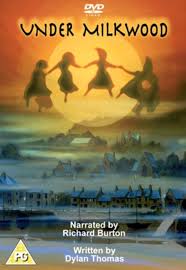

The BBC first broadcast Under Milk Wood, a new “‘Play for Voices”, on the Third Programme on 25 January 1954 (two months after Thomas’s death), although several sections were omitted. The play was recorded with a distinguished, all-Welsh cast including Richard Burton as ‘First Voice’, with production by Douglas Cleverdon. A repeat was broadcast two days later.[ Daniel Jones, the Welsh composer who was a lifelong friend of Thomas’s (and his literary trustee), wrote the music; this was recorded separately, on 15 and 16 January, at Laugharne School. The play won the Prix Italia award for radio drama that year.

There were other notable productions in 1954

- 14 February: extracts from the play read at the Dylan Thomas Memorial Recital at the Royal Festival Hall, London.]

- 28 February: a complete reading at the Old Vic with Sybil Thorndike, Richard Burton and Emlyn Williams, adapted by Philip Burton.]

- 10 March: a broadcast by the BBC German Service, translated by Erich Fried as Unter dem Milchwald, followed on 20 September by the first broadcast on German radio itself.

- 28 September: the first BBC Welsh Home Service broadcast. November: the first stage performance, held at the Théâtre de la Cour Saint-Pierre, Geneva, by Phoenix Productions, with props lent by the BBC.

- The following year, 1955, saw the first British stage production, on 13 August, at the Theatre Royal, Newcastle, the first production at the Edinburgh Festival on 21 August and, on 20 September 1957, the first London West End stage production (at the New Theatre).

- The first attempt to bring the play to the screen occurred in May 1957 when the BBC broadcast a televised version narrated by Donald Houston. In 1963, the original radio producer, Douglas Cleverdon, revisited the project and recorded the complete play, which was broadcast on the Third Programme on 11 October 1963. In 1971, Under Milk Wood was performed at Brynmawr Comprehensive School. The production was entirely the work of pupils at the school—from set design, to lighting and direction. With very few exceptions, every character was acted by a different player to allow as many pupils as possible to take part. Scheduled for only one performance – it ran for a week

- The 1972 film adaptation, with Burton reprising his role, also featured Elizabeth Taylor, Peter O’Toole, Glynis Johns, Vivien Merchant and other well-known actors, including Ryan Davies as the “Second Voice”. It was filmed on location in Fishguard, Pembrokeshire, and at Lee International Film Studios, London

In 1988, George Martin produced an album version, featuring more of the dialogue sung, with music by Martin and Elton John, among others; Anthony Hopkins played the part of “First Voice”. This was subsequently produced as a one-off stage performance (as An Evening with Dylan Thomas) for The Prince’s Trust in the presence of HRH Prince Charles, to commemorate the opening in December 1992 of the new AIR Studios at Lyndhurst Hall. It was again produced by Martin and directed by Hopkins, who once again played ‘First Voice’. Other roles were played by Harry Secombe, Freddie Jones, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Siân Phillips, Jonathan Pryce, Alan Bennett and, especially for the occasion, singer Tom Jones. The performance was recorded for television (directed by Declan Lowney) but has never been shown

In 1992, Brightspark Productions released a 50-minute animation version, using an earlier BBC soundtrack with Burton as narrator. This was commissioned by S4C (a Welsh-language public service broadcaster). Music was composed specially by Trevor Herbert and performed by Treorchy Male Voice Choir and the Welsh Brass Consort. Producer Robert Lyons. Director, Les Orton. It was made by Siriol Productions in association with Onward Productions and BBC Pebble Mill. This was released on DVD in October 2008. DVD ref: 5 037899 005798.

In February 1994, Guy Masterson premiered a one-man physical version of the unabridged text at the Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh playing all 69 characters. This production returned for the subsequent Edinburgh International Fringe Festival and sold out its entire run. It has since played over 2000 times globally.

In 1997, Australian pianist and composer Tony Gould‘s adaptation of Under Milk Wood (written for narrator and chamber orchestra) was first performed by actor John Stanton and the Queensland Philharmonic Orchestra.

In November 2003, as part of their commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of Thomas’s death, the BBC broadcast a new production of the play, imaginatively combining new actors with the original 1954 recording of Burton playing “First Voice”. (Broadcast 15 November 2003, BBC Radio 4; repeated 24 December 2004.) Digital noise reduction technology allowed Burton’s part to be incorporated unobtrusively into the new recording, which was intended to represent Welsh voices more realistically than the original

In 2006, Austrian composer Akos Banlaky composed an opera with the libretto based on the German translation by Erich Fried (Unter dem Milchwald, performed at Tiroler Landestheater in Innsbruck, Austria).

In 2008, French composer François Narboni composed an opera, Au Bois lacté, based on his own translation and adaptation of Under Milk Wood. It was created at the Opéra-Théâtre in Metz, France, with staging by Antoine Juliens. The work is for twelve singers, large mixed choir, children choir, accordion, dancer and electronics sounds.

In 2008, a ballet version of Under Milk Wood by Independent Ballet Wales toured the UK. It was choreographed by Darius James with music by British composer Thomas Hewitt Jones. A suite including music from the ballet was recorded by Court Lane Music in 2009]

In 2009 and 2010 a translation in Dutch by the Belgian writer Hugo Claus was performed on stage by Jan Decleir and Koen De Sutter on a theatre tour in Belgium and the Netherlands (e.g. the Zeeland Late-Summer Festival, the Vooruit in Ghent, etc)]

In 2010, a one-woman production of the text was performed at the Sidetrack Theatre in Sydney, Australia, presented by Bambina Borracha Productions and directed by Vanessa Hughes. Actress Zoe Norton Lodge performed all 64 characters in the play.

In July 2011, Progress Youth Theatre (Reading, Berkshire, UK) performed a stage adaptation of the radio script. All visual aspects, such as stage directions, costume, set and lighting design were therefore devised entirely by the youth theatre. The voice parts were shared equally among seven actors, with other actors playing multiple “named” parts (with the exception of Captain Cat, who remained on stage throughout the production)

The BBC Formula 1 introduction to the 2011 Singapore Grand Prix featured extracts of the audio for their opening VT. In 2012, the Sydney Theatre Company staged a production starring Jack Thompson as First Voice and Sandy Gore as Second Voice, with a cast including Bruce Spence, Paula Arundell, Drew Forsythe, Alan John, Drew Livingston and Helen Thomson. The production was staged in the Drama Theatre of the Sydney Opera House.[citation needed]

In 2012, Gould’s 1997 adaptation of Under Milk Wood (written for narrator and chamber orchestra) was again performed by actor John Stanton as part of the Victorian College of the Arts Secondary School‘s inaugural performance at the Melbourne Recital Centre. Gould played piano and worked with the students as a musical mentor.

Guy Masterson of Theatre Tours International has produced and performed a solo version of the play over 2000 times since its world premiere in 1994. It has been performed at the Edinburgh Festival in 1994, 1996, 2000, 2003, 2007 and 2010; in Adelaide, Australia in 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2012; and in London’s West End Arts Theatre.

In 2014, Pip Broughton directed an adaptation of the play for the BBC, starring Michael Sheen, Tom Jones, and Jonathan Pryce.

In October 2014, the BBC launched an interactive ebook entitled Dylan Thomas: The Road To Milk Wood, written by Jon Tregenna and Robin Moore. It deals with the journey from Swansea via the BBC to New York City and beyond.[

On October 25, 2021, Paul McCartney, in the radio broadcast, accessible through You Tube podcast: “Paul McCartney – Talks about The Writing/Lyrics Of 10 Of His Songs – Radio Broadcast 25/10/2021”, reveals that the Dylan Thomas radio drama/play “Editing Under Milk Wood” portrait of a small town through its town characters was one of the inspirations for the lyrics in the Beatles classic song “Penny Lane”.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!