SONGS AND FILMS FROM BOTH SIDE NOW

Monday 16th January 2023

SONGS AND FILMS FROM BOTH SIDES NOW

by Peter Pearson and Norman Warwick

An e mail from a regular reader, Peter Pearson, always is filed in the column headed ´why didn´t I think of that?´ An e mail from Peter invariably means one or all of a) the artist about whom I have just posted an obituary is alive and well and living in Norfolk b) a song I had said was written by Townes Van Zandt was written by Bert Smith in Somerset or c) he has a blindingly obvious idea that would improve coverage for our readers that that I haven´t thought of yet.

Today, I know for certain his email this morning has achieved at least c, and I can only ray that this article doesn´t alert him to any deficiencies in a or b.

I was listening to the Radio 4 Today programme the other morning which included a feature on the recently released film, Till.

It quickly brought to mind the Emmylou Harris composition, My Name Is Emmett Till, from her Hard Bargain album (left). It has always been one of my favourite of hers. Whilst chewing this over in my mind I then turned to your blog and hey presto there was the piece on Emmylou, called Joy At The Lost And Found (published on Tuesday 10th January 2023).

a statue of Emmett Till is shown in our cover photograph at the top of the page.

Great,…. I love serendipity. That piece can be found in our easy to negotiate archives of over 800 articles if readers want to check out the coincidence.

You know I love to consider myself the fount of all knowledge on events all across the arts but to be honest, even though it has such a vibrant arts scene and Lanzarote does get occasional visits from artists of international renown, there is, nevertheless, a reason why small islands are so accurately described as remote. It is a strange phenomenon, I think, that as technology opens up communications around the world there now seems not enough time to keep up with developments.

So, I´ll be honest. I hadn´t heard of the film Till, till you mentioned it! At first I wasn´t sure what it might be about, and at first I just assumed it to be a rom com of some sort, and I am not sure these days that the title alone would lead us to the Emmylou song you mention, or its relationship to a piece by Dylan (right) and not even to the name of the subject of those songs. Do people still remember that story do you think?

Well, I´ve been thinking maybe you might consider writing a piece linking the two songs and to consider how so often, a 3 minute carefully crafted song can tell a story often better than a 2 hour film.

Bob Dylan, in 1962, wrote the song called The Death of Emmett Till.

Similarly he wrote Hurricane about the wrongful conviction of the boxer-Reuben Carter. Having since read the book and seen the film I still think the song tells it all in a much more concise manner. I am sure you can think of other examples.

You know I agree with you about how epic stories can be told in a perfectly disposable pop song. In this case we are considering real-life historical events of course, but I have always thought Waterloo Sunset by The Kinks captures a world of emotions, crowds of characters, the bustle of a city and the splendour of a sunset.

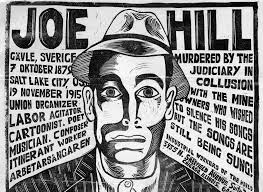

As your e mails invariably do, you have sent me scurrying down new sidetracks and detours that are already making me as dizzy as Tommy Roe as they lead me hither and thither. My first thought on reading your e mail was of the film bio-pic of Joe Hill a unionist and organiser. I had never heard of him, then, but my grammar school girlfriend of the time had. So, off we traipsed down Oxford Road in Manchester to a blue movie emporium posing as an art-house cinema (These were the more falsely innocent years of the late sixties).. The lights went down, the opening credits rolled, supported by a recording Joan Baez singing the title track of the film. My clever grammar-school girlfriend had never heard of Joan,… but I had, and because the lyrics of the song, in three and half minutes or thereabouts, gave such an insight into Hill´s life I sat back end enjoyed the film far more than my girlfriend did !

Joe Hill, born Joel Emmanuel Hägglund and also known as Joseph Hillström, was a Swedish-American labour activist, songwriter, and member of the Industrial Workers of the World. A native Swedish speaker, he learned English during the early 1900s, while working various jobs from New York to San Francisco. Hill, an immigrant worker frequently facing unemployment and underemployment, became a popular songwriter and cartoonist for the union. His most famous songs include “The Preacher and the Slave“[4] (in which he coined the phrase “pie in the sky“),[5] “The Tramp“, “There Is Power in a Union“, “The Rebel Girl“, and “Casey Jones—the Union Scab“, which express the harsh and combative life of itinerant workers, and call for workers to organize their efforts to improve working conditions.[6]

In 1914, John G. Morrison, a Salt Lake City area grocer and former policeman, and his son were shot and killed by two men.[7] The same evening, Hill arrived at a doctor’s office with a gunshot wound, and briefly mentioned a fight over a woman. He refused to explain further, even after he was accused of the grocery store murders on the basis of his injury. Hill was convicted of the murders in a controversial trial. Following an unsuccessful appeal, political debates, and international calls for clemency from high-profile figures and workers’ organizations, Hill was executed in November 1915. After his death, he was memorialized by several folk songs. His life and death have inspired books and poetry.

The identity of the woman and the rival who supposedly caused Hill’s injury, though frequently speculated upon, remained mostly conjecture for nearly a century. William M. Adler’s 2011 biography of Hill presents information about a possible alibi, which was never introduced at the trial.[8] According to Adler, Hill and his friend and countryman Otto Appelquist were rivals for the attention of 20-year-old Hilda Erickson, a member of the family with whom the two men were lodging. In a recently discovered letter, Erickson confirmed her relationship with the two men and the rivalry between them. The letter indicates that when she first discovered Hill was injured, he explained to her that Appelquist had shot him, apparently out of jealousy.

When Joan Baez sang the line ´I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night alive as you and me´ …

Few people outside America and Sweden had heard of Joe Hill before Joan Baez performed the Hayes /Robinson song (1938) in the legendary Woodstock festival, the movie of which was released in 1970; Joe Hill became famous overnight and it’s no coincidence the subsequent film about his life included her version of the song is heard during the cast and credits, at the beginning and at the end of the movie.

The very same year ,two other political prisoners ,unfairly executed ,Sacco and Vanzetti ,were the subject of Guido Montaldo’s movie and again, Baez sang the song Here´s To You to music by Ennio Morricone ,which was a big hit almost everywhere (except in both the US and the UK)

In the film of Joe Hill the tiole character was excellently played by Thommy Berggrens ,whose performance was described by one critic as absolutely mind-boggling, probably based on the trial scene where Hill demands to defend himself,because he knows his so called lawyers are bribed and that it’s a travesty of a trial.

Maybe because he was viewed, even in the sixties and seventies as being too red, too “commie”, tainted by association with the subject of the film Berggrens never became the bug star his performance suggested he deserved to be.

It seems that his political awareness stems from the way religion deals with poverty: the Salvation Army’s canticles provide a sharp contrast with Joe’s revolutionary and foot-tapping song : he does not ask for pie in the sky but a square deal for the underprivileged,, exploited by the wealthy bosses who treat them like dogs, bully and humiliate them ( the scene when they force them to kiss the American flag is revealing). Joe was a generous hero ,-the actor’s boyish look makes wonders- his final testament is deeply moving ,his spirit lives on, “where working men defend their rights, it’s there you’ll find Joe Hill.”

Rotten Tomatoes, who submit observations that reflect their name, reviewed the film by saying Joe Hill (Thommy Berggren) immigrates to America from Sweden in the early years of the 20th century. Although he secures a few jobs in his new homeland, the degrading working conditions astonish him. He becomes involved in the radical organization Industrial Workers of the World and goes on to write folk ballads championing the rights of the average worker. But in 1914 circumstantial evidence links him to a murder. Joe claims he is innocent, but the authorities think otherwise.

Another slightly unusual piece. This is in the way of a tribute to Sven Wollter, a Swede who died on 10th November, and it also gives me the opportunity to introduce ‘Joe Hill’.

Sven Wollter was an actor with quite a Hollywood film and TV reputation and a gravelly-voiced baritone singer. He was a long-time member of the Swedish Communist Party and in 2018 he received the Lenin Award, named after Vladimir Lenin.

This perhaps goes some way to explaining his connection with Joe Hill, who would be the most famous Swede you never heard of except that he isn’t too well known there, either.

So who is Joe Hill? You’d be forgiven for not knowing but he is a hugely significant figure in the music universe. Hill, born Joel Emmanuel Hägglunde in Gävle, north of Stockholm, migrated to the USA in 1902, working his way across the country and becoming a labour activist through membership of the Industrial Workers of the World movement. He became a songwriter and cartoonist for the IWW, releasing popular songs such as ‘The Rebel Girl’ and ‘The Preacher and the Slave’, in which he first coined the phrase “pie in the sky” in the line “you’ll get pie in the sky when you die”. He has come to be regarded as an icon of the workers movement, firstly in the U.S., and later globally, the father of protest music and the Bob Dylan of his day. Dylan said of him,

Joe Hill had the light in his eyes

In 1915 Hill was executed following a controversial trial for murder (some say he was “fitted up” by bosses and even by one of the unions) despite local and international appeals for clemency, two of which came from the then-President Woodrow Wilson.

A poem written in 1930 about Hill, who has been described as “the last Swedish hero” and called ‘I dreamed of Joe Hill last night,’ was turned into a song in 1936 and Joan Baez released her version of it in 1970, having performed it at Woodstock the year before. In it, Hill replies to the statement, “But Joe, you’re ten years dead”, with “I never died”, and in a way he didn’t. His life and death have also inspired books and poetry and it is said that “his spirit lives on in every left winger, Socialist and Trade Unionist.” Others to have recorded this song or otherwise sung about Hill include Paul Robeson, Pete Seeger, Patti Smith and ‘the Boss’, Bruce Springsteen.

There is a Joe Hill museum in Gävle and a small band of people constantly working to keep his memory alive over a century after his death. I’m often surprised when I talk to active trade unionists here in the UK. Most of them certainly know of him. There is – or at least was – an annual Joe Hill Memorial Award night in Sweden with past recipients of the Laureate including Joan Baez and Patti Smith.

Sven Wollter’s version of the song is here (one of seven by different artists on Spotify), followed by links to Baez’s live performance at Woodstock and one by Springsteen from 2014.

Another film / song symbiosis that comes to mind has two different art forms telling the biography (also available in book form) of Loretta Lyn. Much as I loved the performances of Tommy Lee Jones as Loretta Lyn´s father and by Sissy Spacek, in the role of the title character in the film Coal Miner´s Daughter, I have always felt that a chronologically ordered soundtrack by Loretta told the story just as well.

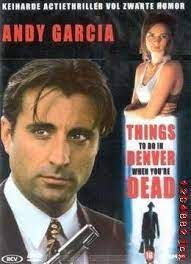

I have always found it fascinating when art works in different genres share of misappropriate titles. Similarly I have always been attracted to clever nonsensical titles, so Things To Do In Denver When You´re Dead ticks both those boxes. The lyrics were written by the late Warren Zevon, of course, and was the title, too, of his 1991 album.

The film of the same name was also released in 1995 American crime story directed by Gary Fleder and written by Scott Rosenberg. The film features an ensemble cast that includes Andy García, Christopher Lloyd, Treat Williams, Steve Buscemi, Christopher Walken, Fairuza Balk and Gabrielle Anwar.

The film’s title comes from a Warren Zevon song of the same name, recorded on his 1991 album Mr. Bad Example, which he allowed under the condition that the song be played during the end credits. The lead character’s name, “Jimmy the Saint,” comes from the Bruce Springsteen song “Lost in the Flood” from his 1973 album Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. The film was screened in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1995 Cannes Film Festival.

Trying to go straight, ex-gangster Jimmy “The Saint” Tosnia runs Afterlife Advice in Denver, where dying people videotape messages for their loved ones. His business isn’t doing well and his former boss, a local crime lord known as “The Man With The Plan,” has bought up his debt in order to command a favor involving the crime lord’s son, Bernard, who has been arrested for child molestation. The Man With The Plan, who was left a quadriplegic after an attempt on his life, wants Jimmy to persuade Bernard’s ex-girlfriend Meg to come back to him; The Man With the Plan believes this will cure Bernard of his pedophilia.

A reluctant Jimmy recruits his friends Easy Wind, Pieces, Big Bear Franchise and the rage-prone Critical Bill. The plan is to have Pieces and Critical Bill pose as police officers, intercept Meg’s current boyfriend, Bruce, and intimidate him until he agrees to break up with Meg. Things go wrong when Bruce grows suspicious of the two men’s identities and mocks them, whereupon Critical Bill stabs Bruce in the throat. The commotion wakes up Meg, sleeping in the back of Bruce’s van. Meg’s appearance startles Pieces, who accidentally shoots her dead. The Man With The Plan is furious at the outcome of their botched mission. He informs Jimmy that he will allow him to live, as long as he leaves Denver, but his crew have been sentenced to “buckwheats” – to be assassinated in a gruesome and painful manner.

Jimmy’s friends come to terms with their impending deaths as they are stalked by a hit man, Mr. Shhh, who never fails. Pieces accepts his fate, with Mr. Shhh providing a quick death. Easy Wind goes into hiding with a gang lord called Baby Sinister, but is given up after Mr. Shhh infiltrates and kills most of Sinister’s entourage. Because Franchise has a family to raise, Jimmy pleads with The Man With The Plan to spare his life. The Man With The Plan agrees to Jimmy’s terms but betrays him anyway by having Franchise killed. The betrayal makes Jimmy vengeful; in turn, Jimmy is also sentenced to die.

Mr. Shhh finally locates Critical Bill holed up in his apartment, but is ambushed by Bill and the two end up killing each other. In the wake of Mr. Shhh’s death, the contract on Jimmy falls to a trio of Mexican brothers. In his final hours, Jimmy says goodbye to a young woman he had fallen in love with, Dagney. Knowing that he will most likely be killed, Jimmy murders Bernard for all the misery he indirectly brought upon the group. He also impregnates Lucinda, a prostitute, in order to fulfill her wish of becoming a mother. In a pre-recorded Afterlife Advice video, Jimmy gives life advice to his unborn child. The trio of killers catches up to Jimmy and he takes his death gracefully. The Man With The Plan is seen mourning his son’s death. Jimmy and his friends are then seen together having “boat drinks” in the afterlife.

My favourite-ever movie critic, Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times summarised it fairly archly when he wrote “On balance, I think it’s an interesting miss, but a movie you might enjoy if (a) you don’t expect a masterpiece, and (b) you like the dialogue in Quentin Tarantino movies !¨

The song and the film did not really tell the same story but I have to admit to enjoying Zevon´s three and half minutes synopsis and character description, that I still play frequently, much more than I remember enjoying a circa 90 minute film I forgot about almost entirely the day after I saw it.

Of course, there are plenty of films that have borrowed song titles to share the name even though the film might be only very tenuously attached to the song´s premis. We can think of Pretty Woman, American Pie and Boys Don´t Cry.

The association between The Hurricane, Bob Dylan, Emmett Till, Emmylou and Mr. Dylan again, seems much more substantial.

In November 2018 Time magazine published an article in its History section, stating

´There are many startling things about the Emmett Till case. But, 63 years after his death, perhaps the most startling of all is the fact that Americans know his name, even recognize his face.

Back in the summer of 1955, when J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant savagely beat the 14-year-old Chicago kid, shot him in the head, weighted his body down and dumped it in the Tallahatchie River, they thought that was the end of it.

Till had whistled at Bryant’s wife Carolyn, or spoken suggestively to her, or laid hands on her — the story kept changing. It was the classic Southern tale of a black male accused of violating the region’s taboo against interracial intimacy. Literally thousands of African American men were lynched under such accusations.

The civil rights leader Aaron Henry once remarked that the most surprising thing about the Till story was not its horror but the fact that white people even noticed. After all, black boys had been lynched for decades with impunity. African American bodies were not supposed to reemerge, and they certainly were not supposed to stir national and even international outrage

But this one did. Killing Till and dumping his body did not end the story, quite the contrary. Thirty-eight articles in TIME magazine have discussed Emmett Till since 1955. Daily newspaper databases reveal even more extensive coverage. In the New York Times alone Till appears in 600 articles.

Most of the Till coverage came in the first six months: The discovery of the body; the deeply emotional funeral in Chicago (to which 100,000 South Siders came to pay their last respects); the indictments and trial, when nationally famous reporters swarmed tiny Sumner, Miss., and television cameras caught the scene outside the courthouse. Day after day, Till was headline news.

But then the story disappeared. There were few articles in the press commemorating the tenth anniversary of the Till slaying, even fewer on the 25th. Early histories of the Civil Rights Movement barely mentioned him.

More accurately, the Till story became segregated, living on among African Americans, not whites.

Young black activists, who sometimes referred to themselves as “the Emmett Till Generation,” carried his memory into their struggles of the ’60s. John Lewis, Anne Moody and Muhammad Ali all recalled their shock at seeing Till’s funeral photos in Jet magazine, Emmett in his coffin, his face a grizzly ruin. They recalled too how the story gave them grim determination to change things. The photos became part of “Jim Crow wisdom,” visual lessons parents gave children about growing up African American.

Seared though they were into the memory of the Till Generation, very few whites saw those pictures. No mainstream newspapers or magazines published them in 1955, or for three decades thereafter.

That changed in 1987 when the photos reemerged, most prominently in the popular documentary Eyes on the Prize, which began its history of the Civil Rights Movement with Emmett Till. Rather than avoid Till’s face, Eyes on the Prize lingered on it. Only then did the truism that Emmett Till’s martyrdom launched the Freedom Struggle start to take hold among whites.

What about the Till story today? Look more closely at those 600 Times articles focused on Emmett Till. One-third of them appeared in the last five years, and it is roughly the same for other newspapers and magazines. Histories, novels, television reports, news stories, websites, on-line publications, historical markers, scholarly essays, documentaries—all have come with growing frequency this century.

Current events brought Emmett Till’s name back. Oprah Winfrey called the Till memorial in Washington’s new African American History Museum “profound,” and added that Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Laquan MacDonald gave us “a new Emmett Till (left) every week.” A few months later, LeBron James held a press conference when someone painted an ethnic slur on his front gate. The first thing James talked about was Mamie Till Bradley’s refusal to be silent in the face of her son’s murder. Then late last year, Dave Chappelle ended his comedy special by discussing Carolyn Bryant’s confession that Emmett Till did nothing to deserve his fate.

This year alone, Emmett Till was in the headlines again when someone shot up the historical marker where his body was dumped, then again when Carolyn Bryant recanted her recantation that she lied about Till back in 1955, and again when the FBI announced it would reopen the case.

Why so much attention to a story once mostly forgotten? Because it speaks to our growing awareness that racism is on the rise, that it did not disappear with slavery or Jim Crow, that we never became a “post-racial” society.

Till’s is a story we can grasp, not of unnamed millions but of a single knowable martyr to racial hatred. The sadism of his killers, the horrific beating they inflicted on the boy still shock us today. The Till case also reminds us of our long history of racism in criminal justice, from policing all the way through trial and incarceration. His fate reminds us too that white supremacy was never just a set of ideas and opinions, but a charter for violence inflicted on living bodies.

Above all, the face of Emmett Till embodies America’s tragic racial history, the good-looking lad smiling on Christmas Day, that same innocent face smashed to a hideous death mask on the long lonely Mississippi night of his murder.

Racism is the shape-shifting demon that America wrestles once again. Lies proliferate about minorities, the kind that got young Emmett Till lynched. So we continue to retell his story, to probe its meanings, to expose and explain what happened. Just as Anne Frank became the young martyr whose story helps us grasp Nazi horror, so Emmett Till’s is the face that reveals white supremacist depravity. His ghost haunts us because his murder exposes racism’s bloodthirsty heart.

And so, 63 years later, we know his face, we know his name. In his lynching lies shame, in remembering it lies hope.

Elliott Gorn is Professor of History at Loyola University Chicago. He is author of Let the People See: The Story of Emmett Till available now from Oxford University Press.

Somewhere amidst all the above points nudging us towards an understanding and tolerance we have yet to fully realise, is the Bob Dylan song on the subject.

“The Death of Emmett Till“, also known as “The Ballad of Emmett Till“, is a song by American musician and Nobel Laureate Bob Dylan about the murder of Emmett Till. Till, a 14-year-old African American, was killed on August 28, 1955, by two white men, after being accused of disrespecting a white woman. In the song’s lyrics,

While the song never appeared on any of Dylan’s studio albums, it did appear on a number of bootlegs. One bootlegged performance, which was recorded from Cynthia Gooding‘s radio show called Folksinger’s Choice sometime in early 1962, starts with Dylan saying that the melody is based on chords he heard from folk musician Len Chandler.[2] The melody is quite similar to “The House of the Rising Sun” from the album Bob Dylan. Dylan’s performance of the song was released on the 1972 album Broadside Ballads, Vol. 6: Broadside Reunion, under the artist name Blind Boy Grunt. Another recording, taped as a demo for music publisher M. Witmark & Sons and also bootlegged for many years, was released on The Bootleg Series Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos: 1962–1964 in October 2010.

Writer Stephen Whitfield has also served as a visiting professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium, the University of Paris IV (The Sorbonne) and the Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich.

Since 1976 Whitfield was associated with the Southern Jewish Historical Society and he published a series of essays on the history of the Jews of Southern United States.[1]

He earned the following degrees: Brandeis University, Ph.D. (1972), Yale University, M.A., Tulane University, B.A.

The writer (born 1942]) was the Max Richter Professor Emeritus of American Civilization at Brandeis University, where he taught after receiving his doctorate there in 1972 until 2016. His main interests included 20-century American political and cultural history and American Jewish history

Whitfield called Dylan´s lyrics “mawkish” but described “the ballad” as “a precocious attempt to continue the tradition of the folk protest song.”

Personally, I think there is a marked brevity to Dylan´s lyric although it still tells a nuanced story of the events leading up the young man´s detainment.

This was perhaps a foreword, rather than the story in full. As was his wont in those early days of his career there is something old timey, almost medieval tone to Dylan´s vocabulary and phraseology, though I think that both Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark (and Tom Paxton, maybe) handled this particular skill with more dexterity at that time. There is, however, something in Dylan´s style and the urgent and angry and yet somehow resigned way he tells the tale that lends it an immediacy and paints a picture we recognised then,…. and still recognise now.

The story of Emmett Till grows exponentially in the wake of the past fifty years with its freedom marches, suppression and Black Lives Matter confusions.

Another chapter in the story was written by and recorded by Emmylou and now this new film is likely to re-awaken debates about both her song and Dylan´s.

Emmylou recorded My Name Is Emmett Till, and as you say Peter, was released on her Hard Bargain album in 2011. As she narrates the story, Emmylou adopts the first person voice of the subject and survives the risk of gender confusion to deliver the tale as poignantly as does Dylan in his song.

Among the ´interesting´ reviews for the Hard Bargain album at the time was one that caught my eye in the Uncut magazine that was written by Neil Spencer.

She is rarely creatively inactive, he wrote, almost always touring and joining forces with one fellow traveller or another, but fans of Emmylou Harris might nonetheless feel they have been handed meagre rations over recent years.

For all its commercial success, All The Roadrunning, her 2006 partnership with Mark Knopfler, was a patchy affair, at least if you aren’t partial to the Knopf’s growl. 2008’s All I Intended To Be felt even more like a stop-gap, its handful of new songs augmented with judicious covers of Merle Haggard, Tracy Chapman and others.

Hard Bargain brings us back to Emmylou herself. All but two of its 13 songs are self-penned, the exceptions being Ron Sexsmith’s title track and “Cross Yourself”, a pleasant but lightweight contribution from Jay Joyce, who also produced the album and multi-tracked its guitars. For company Joyce had just percussionist Giles Reaves, plus Emmylou herself on acoustic guitar. The sound is lean without being minimal – there isn’t much ‘downhome’ about it, no pedal steel or mandolin (though there is a sprinkle of banjo), but plenty of rock muscle when needed. Indeed, Joyce seems to aspire to the cavernous approach of U2 or the ricocheting ambience/empty echo (delete according to taste) that Daniel Lanois brought to Emmylou’s 1995 Wrecking Ball. At times she seems to be singing from the bottom of a well.

As I remembered that review I perhaps assumed too quickly that it would have included a reference to My Name Is Emmett Till.

In truth, though, I had to search hard to find any such references anywhere. Although they didn´t review the song per se, the ever reliable Songfacts have said that in 1955, the 14-year-old African-American Emmett Till was murdered in Mississippi after he was seen flirting with a white woman, 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant. The trial attracted a vast amount of press attention. Bryant’s husband Roy and his half-brother J. W. Milam were acquitted of Till’s kidnapping and murder, but months later, protected by double jeopardy, they admitted to killing him in a magazine interview. Till’s murder is noted as one of the leading events that motivated the African-American Civil Rights Movement. This song finds Harris recounting the story in a heartbreakingly plain-spoken narrative, told from the murdered victim’s perspective.

Other references to Emmett Till in popular music include John Coltrane’s “Bakai,” whose title was used in memory of the murder victim. Also in his single “Through The Wire,” Kanye West raps that he looked like Emmett Till after he’d been in a car accident.

I did find a piece on Folkworks on line, written by Ross Altman PhD that shed some more light, even if from a different angle, within the context of a live review.

Emmylou Harris and The Red Dirt Boys crashed this bastion of high culture last night and all I could think was, “Who let them in?” There goes the neighborhood.

On the day they hand out the Nobel Prize for Physics and Chemistry they bring this Southern Belle in black boots and jeans and black Levi jacket and black blouse singing songs about the whores on 2nd Avenue, and a couple outlaws named Pancho and Lefty, and quoting some scripture called “Every Grain of Sand” from a pseudo-poet from Hibbing, Minnesota—so far north that Emmylou let it slip he might as well have been from Canada—where all those draft-dodgers fled during the Vietnam War. She allowed that she liked his songs too, and forgot to mention that he fooled the Swedish Academy into awarding him the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The fade away to Bob Dylan’s song resulted in the most charming moment of the concert to me: She looked up and smiled, “I remembered all the words! No teleprompter! The day I start to use a teleprompter is the day I retire.” Amen!

She also wondered aloud if it hadn’t been for him, where would music and language be today? Well, I don’t know and I don’t care. Milton and Shakespeare would still be here, not to mention Tennyson and William Blake. Well, as Wallace Stevens said, there’s no accounting for taste—one likes what one happens to like.

And I like Emmylou Harris—so does the National Recording Academy, who gave her 14 Grammys—and the 2018 Lifetime Achievement Award. Is it any wonder she slipped through the back door of the Country Music Hall of Fame? Johnny Cash is there—Hank Williams is there—George Jones is there—so is Willie Nelson. And with a bigger voice than all of them put together, so is Emmylou Harris: Big voice—and big guitar—a Gibson J-200—a big blonde one. They both looked and sounded gorgeous.

Emmylou comes from Birmingham, Alabama—known for only two things: Martin Luther King’s “Letter From the Birmingham Jail;” and the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church that killed four black girls on September 16, 1963. Wonder why they would want to remind me of that history. To answer that question, you need to go back sixty three years—to 1955.

Trivial Pursuit, Country Music Edition: How many Country Music Hall of Fame members have written a song about Emmett Till, the black teenager whose murder sparked the civil rights movement and inspired Rosa Parks to refuse to move to the back of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama on December 1, 1955? Spoiler alert: just one, and she is the reason I’m at Royce Hall tonight. Her name is Emmylou Harris and it’s not her fourteen Grammy Awards that made me want to attend her concert for the Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA. It’s her song for the fourteen year-old boy who was tortured and murdered on August 28, 1955 in Money, Mississippi—one of the many unsolved crimes against black people during the civil rights movement. No one has ever served a single day in prison for his murder. And no one else in the Country Music Hall of Fame has ever written or said a word about it. But Emmylou Harris is not like anyone else in the Country Music Hall of Fame. She is one of a kind, and it’s an honor to be here.

Her birthplace was part of her introduction to her song, My Name Is Emmett Till. Well, there you go Emmylou—no wonder they say you don’t fit into Nashville. She plays it like a folk singer—finger-style in drop “D” tuning. And for more than half the song her band lays off—it’s just Emmylou and her big Gibson J-200. Then slowly at first, so you just barely hear them, the Red Dirt Boys with Will Kimborough on lead guitar, Phil Maeira on keyboards, Eamon McLaughlin on fiddle, Chris Donohue on standup bass and Bryan Owings on drums, create a somber, beautiful undertow of sound to complement her haunting lyrics:

My Name Is Emmett Till

I was born a black boy

My name is Emmett Till

Walked this earth for 14 years

One night I was killed

For speaking to a woman

Whose skin was white as dough

That’s a sin in Mississippi

But how was I to know?

I’d come down from Chicago

To visit with my kin

Up there I was a cheeky kid

I guess I’d always been

But the harm they put upon me

Was too hard for what I’d done

For I was just a black boy

And never hurt no one

And then the heartbreaking, moaning refrain, with echoes from Abel Meeropol’s classic anti-lynching song Strange Fruit, sung by Billie Holiday:

Oh oh oh oh oh oh

Oh oh oh oh oh oh…

They say the horror of that night

Is haunting Heaven still

Where I am one more black boy

My name is Emmett Till

If Emmylou is known for “alt-country” this is as alt-as it gets—a lamentation for the inheritance of the South and America’s original sin of slavery. Robert Frost once wrote that mediocre poetry comes out of grievances—great poetry is inspired by grief. That’s a distinction Harris recognizes, and rises to Frost’s bellwether of great poetry. Townes Van Zandt made a similar distinction—and Harris reminded her audience of it last night: “There are two kinds of music—the blues and ‘Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah.’” Harris is drawn to the former, and that’s what makes her a great artist. She did more than quote Van Zandt—she sang his greatest song as her first encore—Pancho and Lefty—and if I never hear another performance of it I can be confident I’ll remember the best—it was transformative—

All the Federales say

They could have had him any day

They only let him slip away

Out of kindness I suppose.

Emmylou Harris owns the song as far as I’m concerned, and with Burl Ives’ passing she also owns his theme song—the hymn The Wayfaring Stranger.

Now we know why Gibson Guitars of Bozeman, Montana filed for bankruptcy earlier this year. They don’t sell guitars—they give them away—two big beautiful blonde J-200s to Emmylou Harris for this tour. She introduced them with the same charm and dedication she introduced the band—they were part of it after all. She stopped playing her signature guitar some time back because they were starting to wear on her back—she tried Pilates and playing a “smaller, ordinary guitar,” until her strength returned, and is now proud to say, “We’re back!” referring to her J-200. Highlighted against her woman-in-black denim outfit it shines like a star.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P0oemBPggGI

“Cosmic American Music” Gram Parsons called it—his then revolutionary fusion of country, rock, folk and blues—all of which her great band understands and propels to the forefront depending on which song is at hand, and that’s the kind Emmylou plays and sings. Forty-five years after his tragic death from drugs and alcohol—which even his friend Keith Richards knew not to mix—on September 9, 1973 in Joshua Tree National Forest—Emmylou Harris is still singing her tributes to Parsons. She includes all three, From Boulder to Birmingham (her dynamite encore about the Laurel Canyon fire of 1973)—when Parsons died—Michelangelo—her high culture elevation of her singing partner/romantic aspiration for too few years—where she also compares him to Picasso “with a scar across your shoulder”—and her heartbreaking song for him, 1985’s “Sweetheart of the Rodeo,” evoking the Byrds’ landmark album from 1968, when Gram Parsons had joined them and convinced them to record it in Nashville and go all-in country.

And finally, from her second encore to a nearly packed Royce Hall standing ovation, she sings her final words of the night to the ghost of Gram Parsons:

Well, Emmylou, I would walk all the way from Boulder to Birmingham if I thought I could hear your voice. It made the walls of Royce Hall come tumbling down.

With thanks to Holly Wallace of CAP-UCLA for the press pass, and Nicole Freeman of the Ace Agency, who has taken over her responsibilities, for the aisle seat in the orchestra section—and putting me on the guest list for the pre-concert CAP-UCLA lounge for Donors. Ace Agency is a class act!

Los Angeles folk singer Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature from SUNY-Binghamton; belongs to Local 47 AFM; may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com

When I listen again to the lyrics of Emmylou´s Emmett Till song, (and much as I love her I confess the album is not high among my play-lists) I note that, as I heard in the Ballad Of Joe Hill sung by Joan Baez to introduce the film, of the same name, Emmylou´s song seesm to offer a synopsis, that I have no doubt the new film will turn into episodic chapters.

Till (right) , the film you mentioned Peter, had escaped my attention thus far but I have since found out is a 2022 biographical drama film directed by Chinonye Chukwu and written by Michael Reilly, Keith Beauchamp, and Chukwu, and produced by Beauchamp, Reilly, and Whoopi Goldberg. It is based on the true story of Mamie Till-Bradley, an educator and activist who pursued justice after the murder of her 14-year-old son Emmett in 1955. The film stars Danielle Deadwyler as Mamie Till-Bradley, with Jalyn Hall, Frankie Faison, Haley Bennett, and Goldberg in supporting roles.

The film was officially announced in August 2020, though a project about Emmett Till’s murder had been in the works for several years prior. Much of the main cast joined the following summer, and filming took place in Bartow County, Georgia that fall. It is the second major media property based on Mamie Till to be released in 2022, following the television series Women of the Movement. The film is dedicated in memory of Mamie Till’s life and legacy and its release coincided with the October 2022 unveiling of a statue in Emmett Till’s memory in Greenwood, Mississippi.[5]

Till had its world premiere at the New York Film Festival on October 1, 2022, was theatrically released in the United States on October 14, 2022, by United Artists Releasing, and was released in the United Kingdom on January 6, 2023, by Universal Pictures. The film received positive reviews, with Deadwyler’s performance garnering widespread acclaim, and was named one of the best films of 2022 by the National Board of Review.[6] It has grossed $9 million against a production budget of $20 million.

Again, the most considered review I could find of the film was pnon the Roger Ebert web site.

“Till” tells the story of the murder of Emmett Till and the activism of his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley. It is the second retelling of this story in 2022, after the January ABC miniseries “Women of the Movement.” One may think that two filmed versions of the same story in such a short amount of time may be overkill. But the constant attempts by one political party to censor historical events that make White folks uncomfortable require these stories remain in the public consciousness. They have to be retold, much like the oral historians in my family passed Emmett Till’s story down to me when I was a little boy. Those who feel that these events are “in the past” and that we should get over them, need only be reminded of this New York Times article whose headline is “Emmett Till Memorial Has a New Sign. This Time, It’s Bulletproof.” As late as 2019, people were putting bullet holes in a sign that marked the site of a lynching.

Through Till-Mobley’s actions, we know about the death of her son, and how hideously he was brutalized. Director Chinonye Chukwu and her co-screenwriters, Keith Beauchamp and Michael Reilly aim to give viewers a glimpse of who Till was before he was murdered. Played by Jalyn Hall in the first third of the film, he’s the typical 14-year-old. Chukwu documents him getting dressed and ready for his trip down South to visit his cousins. He has the usual “but Mom” teenager moments with his mother, Mamie (Danielle Deadwyler), who in turn has the same moments with her own mother, Alma (Whoopi Goldberg). “That’s the ‘Mama, mind your business and go home’ face,” she says when Mamie silently expresses her displeasure over an opinion, a funny line in a film that is not without humor.

It’s Alma’s idea to send Emmett down to visit his Southern kin. Raised in Chicago, he had a different set of interactions with White people than his cousins Simeon (Tyrik Johnson) and great uncle “Preacher” Mose (John Douglas Thompson) would have, though the film implies that Emmett was unfamiliar with how dangerous slights against White people could be. Chicago is certainly not without racism, as a scene in a department store shows. The cousins joke about how funny it’ll look when their Yankee relative is down there helping Mose pick cotton on the farm where he sharecrops.

Before he leaves for Money, Mississippi, Mamie repeatedly broaches the subject of Southern dangers with Emmett, whom she calls Bo. Each time, he gives her the “but Mom!” teenager brush-off. She knew that a political organizer, Lamar Smith, had been murdered down there the week before for being “a rabble-rouser.” “Be small,” she tells him, which leads to gentle mockery from her son. He just wants to have fun and see the Mississippi Delta. In taking the time to show these scenes, including one where he dances with his mother to their favorite song, “Till” brings Emmett back to us as what he originally was, a teenager just starting his quest for some independence.

As we know, Emmett Till was murdered three days after he arrived in Money. On August 24, 1955, he interacted with 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant (Haley Bennett), a White woman who worked at a store frequented by Blacks. The stories varied as to the details of that encounter, and “Till” takes from several different sources. We see Emmett compare Bryant to a movie star before flashing a picture of a White girl that came with his wallet. That part of the story was disputed by Simeon Wright, who provided his own account of the events of that day in 2015. Wright did confirm Emmett wolf-whistling at Bryant, which the movie depicts. I thought that was a bit confusing, as I’d always been told that Emmett whistled before speaking to help with his stutter, and that was misconstrued by Bryant as meant for her.

No matter. What happens next is not in dispute. Though Chukwu keeps her press release promise not to depict any violence against her Black characters onscreen, she does show several White men and a few Black men forcibly retrieving Emmett from Preacher’s house. The anguish of Thompson’s performance here and the confusion Hall displays will haunt viewers long after the film is over, as will Hall’s off-camera screams in the brief scene where Chukwu alludes to his murder.

From here, “Till” focuses on Mamie Till-Mobley and her attempt to get justice after her son’s disappearance. Deadwyler is astonishingly good here, masterfully navigating every emotion we’d think a mother would have, and then a few we may not have originally considered. Her outrage is palpable as the NAACP lawyers ruthlessly interrogate her relationship with future husband Gene Mobley (Sean Patrick Thomas) and her brief marriage to ex-husband “Pink” Bradley. (Emmett’s father died in World War II.) Later, when her son’s body is found, Deadwyler does some of her best work in the film.

The way “Till” depicts Till-Mobley’s scenes with Emmett’s body are sure to be controversial. Chukwu keeps him obscured when his mother first enters the room, which led me to believe he would not be depicted. Then the camera lifts so we can see the full brunt of the damage done. Chukwu takes her time as we witness Deadwyler touching various parts of her son, sparing nothing. It felt overwhelming, and I was of two minds about this sequence. On the one hand, it felt a bit exploitative despite its undeniable power. On the other, Mamie Till-Mobley wanted the world to see what those men had done to her boy; so strong was her desire that she had an open casket funeral and put his body on the cover of Jet Magazine. Some criticized her for doing this, so in a way, “Till” is honouring this decision.

Anyone who has seen “Clemency,” Chukwu’s 2019 feature with Alfre Woodard, will recognize her love of her actor’s faces, and of the uncomfortable silences that punctuate their performances. When the film depicts Till-Mobley’s testimony in court, Deadwyler is Oscar-worthy. Watch how it looks as if she’s physically convulsing from loss at one moment, and how she then transitions to an unshakable certainty when faced with the defense’s lie that the body she buried was someone other than her son. Once Bryant takes the stand and spins her tale that she was almost raped by Emmett, Deadwyler is riveting in her righteous indignation as she walks out. “I know the verdict already,” she tells her lawyer.

Chukwu gets fine work from all of her actors, including the always welcome Frankie Faison as Mamie’s father. Goldberg is memorable in her few short scenes, and Jayme Lawson is also good in a role Goldberg once played, Myrlie Evers. Hall leaves a lasting impression as Emmett; his naturalistic performance makes him feel even more real to us. The haunting score by Abel Korzeniowski and the editing by Ron Patane ably assist the director in telling this story. Bobby Bukowski’s cinematography reminds us of how beautiful the South can look despite being a backdrop for so many horrible acts of racism.

One of the many things the civil rights movement demanded to see enacted was a federal anti-lynching law. In 2022, such a law was finally passed after decades of failed attempts. It was named after Emmett Till. That it took this long, and the idea that laws are being passed to ensure the reasons why aren’t taught in school, just highlight why “Till” feels so timely. Till’s murderers confessed to Look Magazine for $4,000 after being acquitted, and Carolyn Bryant is still alive and unpunished. That should be enough to justify this movie’s existence. If nothing else, see it for Danielle Deadwyler’s incredible performance. She truly is unforgettable.

I guess, despite the A to Z of sidetracks and detours I have rambled on these pages today, I haven´t really answered your question, Peter, as to which serves us better, á perfectlñy disposable three and half minuted pop song or a ninety minute film.

Most of what I have found and written here seems to be deliberately leading me away from the soul searching necessary to properly answer your question, although there must surely be a subjective response in my head somewhere, Give me time.

What really interest me, though, is whether these songs by Bob and Emmylou sit comfortably in our shared love for what you and I and a handful of others call Americana music.

A handful of others? Really? The UK is an Americana cultural desert pretty much. There are very few visiting concerts on the horizon.

I don´t know if you noticed a reference to The American Music Association UK in yesterday´s post ? Surely there must be some concerts coming in the months ahead.

After vowing never to attend another Lucinda Williams (left) concert after the Apollo debacle, I considered that in the absence of anything else and considering she seems to be a reformed person more recently, I might go to a gig I had noticed she slated for later this month slated on her website.

Sadly she had a stroke last year and mostly performs sitting on a chair. But her Manchester gig is at The Ritz -no seating -standing only- £38 admission. She has a supporting artist of whom I have never heard.

Needless to say I am not going but I wonder what sort of numbers the gig will get. She is, after all, turned 70 as I am at 75 and I would expect most of her supporters will be between 70 and my age. How many of those want to attend a stand up gig at the Ritz. ?

You make good points, there. I think, post-covid that the nature of concert performances of the kind we enjoy will have to change. New Zealnd singer Lorde has already addressed the issues of tour costs, and of stadium concerts, and I reckon tour dates might have to become more niche targeted, which might take us back to the gigs you and I and Ian Johnson, of Stampede Promotions, remember of Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark, John Stewart and Tom Russell in the UK back in the eighties.

.Maybe you´re rioght Norm.. I hear Tom Russell (right) is to play at Bury Met in June but that is only from his UK agents website at the moment. The main promoter of Americana gigs in these parts-Steve Henderson-aka Mr Kite-has no forthcoming gigs and it looks like he might giving it up !.

The primary sources for this article have been various on line sites as attributed. In our occasional re-postings Sidetracks And Detours are confident that we are not only sharing with our readers excellent articles written by experts but are also pointing to informed and informative sites readers will re-visit time and again. Of course, we feel sure our readers will also return to our daily not-for-profit blog knowing that we seek to provide core original material whilst sometimes spotlighting the best pieces from elsewhere, as we engage with genres and practitioners along all the sidetracks & detours we take.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!