KRAYZY DAYS OF CRIME IN THE CAPITAL

KRAYZY DAYS OF CRIME IN THE CAPITAL

by TONY BRADY with background by Norman Warwick

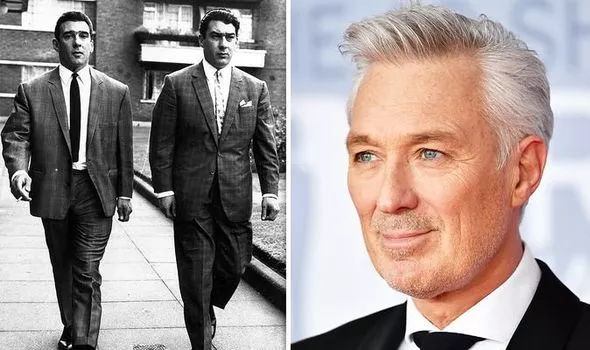

The first major film to be produced about the vicious bullying and retributions dealt out by The Kray Twins was released in 1990 under the simple title of The Kray Twins (left, and their mother).

The first synopsis of that film found by my search engine described the film as following twins Ronnie (Gary Kemp) and Reggie Kray (Martin Kemp) as they are raised in East London, under the influence of their hateful but doting mother, Violet (Billie Whitelaw). As they grow up, Ronnie’s violent nature takes over, and Reggie follows his brother’s lead. The two become notorious crime lords who rule over the East End club scene. But at the height of their power, the brothers veer into different lives, giving the older crime bosses a chance to reclaim what the Kray twins took from them

The real life Kray Twins were said to have “hated” the biopic about their brutal reign in the criminal underworld, which starred brothers Martin and Gary Kemp who had fiorst come to fame as singers and musicians in their own band Spandau Ballet.

Josh Saunders, in the Daily Express, wrote that Ronnie and Reggie Kray are among Britain’s most notorious gangsters. The duo, known as the Kray Twins, carried off murder, armed robberies, assaults and other barbaric crimes with their gang The Firm, in East London. During their reign in the Fifties and Sixties, they gained celebrity status and rubbed shoulders with Frank Sinatra, Barbara Windsor and others. Their exploits were fictionalised in the 1990 film The Krays, which starred Martin and Gary Kemp. This was said to have angered the criminals who explicitly did not like the film.

Hairdresser Maureen Flanagan was thought of like a “little sister” by the gangsters and revealed their candid thoughts about the onscreen adaptation of their crimes. Her insight came from visiting Ronnie in prison after previously getting to know the “frightening” thugs while she cut their mother Violet’s hair.

Ms Flannagan revealed that the Krays particularly disliked scenes that featured their mother, who was played by Billie Whitelaw, because the film showed her swearing.

Ronnie told her “they hated the film” for that reason and felt that director Peter Medak had taken creative liberties with his adaptation.

She said: “When I first went after he’d had a DVD film sent into him he said, ‘I hate that film.’”

Ronnie continued: “How dare they allow our mother to swear. Our mother never swore in her life.”

Ms Flannagan, who cut Violet’s hair every week, admitted that she “could guarantee that” and reiterated their “hatred” for the film.

After the hairdresser had watched the Kemp brothers’ attempt at bringing the Krays to life, she felt that they didn’t portray the reality of such terrifying figures.

She said: “I thought, ‘I’ll go to see the film but if they don’t frighten me then they won’t be Ronnie and Reggie Kray’.

“They had to have this menace and that aura about them. And they didn’t frighten me.”

Ms Flannagan also claimed there was a kinder side to the twins that was left out and recalled that they were “very respectful to women”.

She illustrated her belief with one story about a visit to Ronnie in prison, where he resided for 26 years until his death in 1995, two days after he suffered a heart attack.

Ms Flannagan recalled: “He came to the table and he saw Peter Sutcliffe on the next table and said, ‘I don’t want you sitting next to that s***’.

“He said, ‘Get up and walk around the table.’ He didn’t want me to be in the eyeline of Peter Sutcliffe.”

Ronnie’s twin Reggie died in 2000, two months after he was released from prison on compassionate grounds following a diagnosis with terminal bladder cancer.

During her interview on ITV’s Lorraine, in 2015, Ms Flannagan expressed her belief that Tom Hardy’s 2015 biopic Legend would be a more accurate portrayal.

Ms Flannagan commented: “He’s got everything spot on so it will be a good film.”

So Ronnie and Reggie and associates dismissed the eponymous film The Krays, but it is probably fair to say the film hadn´t been made for their approval.

There was a slight surprise that Martin and Gary Kemp, given their previous careers had been as New Romantics in the pop music vibe of their time, and worked together in their group Spande Ballet.

Roger Ebert (left) was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism. You can find many of his essays at RogerEbert.com

London had never seen anything quite like the brothers Kray, the sadistic twins who ran a protection empire and palled around with cafe society. They became celebrities of a sort. British professional criminals followed a more genteel tradition until the Krays came along in the 1950s and early 1960s. You might have gotten bashed on the head or even, after great provocation, shot dead, but until the Krays, it was unlikely anyone would pull out a sword and redecorate your face.

The Krays got a reputation for performing their sickest crimes themselves, and then turning up, immaculately dressed, at posh nightclubs. The British tabloids made an industry out of them, but what nobody could quite believe was that they really did go back home every night to the humble East End semi-detached home they shared with their Cockney mom.

The genius of “The Krays,” Peter Medak‘s film about the most notorious villains of modern British crime, is that the movie is not simply a catalogue of stabbings, garrotings and bloodletting. It goes deeper than into the twisted pathology of twins whose faces would light up with joy when their mom told them they looked just like proper gentlemen.

Reggie and Ronnie, their names were. Ronnie was the instigator, the one who got off on killing, and Reggie was the weaker one who killed only once, under Ronnie’s insistent pressure, but at the time there was nothing to choose between them: They were the two most feared men in the East End. And their mother, Violet, was treated very, very nicely, wherever she went.

“She was the most important love interest in their lives,” Billie Whitelaw (right) was musing one afternoon after the movie’s North American premiere. Whitelaw is the distinguished British actress who is known as the foremost interpreter of the works of Samuel Beckett, and she plays Mother Kray in the movie. It’s quite a performance.

“Violet was just as well-known as the twins,” she said, “but for different reasons. She was a classic East End mother figure. And the whole focus of the movie is domestic. Violet and her boys. There’s a most horrific film to be made about the Krays, because what Peter Medak has done is just the tip of the iceberg of the atrocities they committed. If you wanted to make a gory horror movie out of the Krays, it’s all there to make. But Peter has actually made a domestic film about a mother and her two sons.” In “The Krays” (opening Friday in Chicago at the Fine Arts), Violet cheerfully rules her husband; her other son, Charlie, and all the neighbors and relatives. She’s a forcible, opinionated, strong-willed woman who knows when she holds her twins for the first time that they’re destined to be special. As children, they were mean and violent, and forged a strange bond of twinship that distrusted the rest of the world – except for Violet. She could see no evil in them.

She doted even on their “business,” which all London knew was extortion.

In the film, the Krays are played by brothers, Gary and Martin Kemp, whose sleek, good looks seem right at home in expensive suits and polished shoes. Their performances suggest an eerie quality to the twins – the notion that they are never entirely offstage, that everything they say is for effect, sometimes ironic effect, and that they are never more dangerous than when their oily politeness is on display.

Whitelaw knew the twins at height of their powers. “I was working at the Theatre Workshop with Joan Littlewood,” Whitelaw remembered, “and they were around then. They actually offered Joan protection, but I think it was a courteous, nice protection. They loved theatricals.” And yet the protection they were offering, I said, was basically protection against themselves.

“I suppose so, yes. But they always wanted to be considered gentlemen. That was very important to them. They behaved with great courtesy. Their brother Charlie, who I know quite well, the oldest one, always behaved with enormous courtesy. And a number of the old gang members who were around when we shot the film were extremely polite on the set. They very much wanted to be considered gentlemen, and in their own way, they are, sending flowers, doing this, doing that, standing up when a lady came into the room.” You’ve been quoted, I said, as telling Charlie you didn’t know if you could get Violet quite right; you didn’t know if you could do her justice in terms of how warm she was, and what a good mother she was.

“I know that these three boys were besotted with their mother,” Whitelaw said. “They all three of them loved her. In fact, everyone I’ve spoken to who knew Violet Kray loved her. I was talking to Charlie about her very early on, in fact, and whenever I started to talk in detail about Violet, tears would come to his eyes. Even her brother loved her, and that’s unusual, isn’t it? For siblings to love one another, and I didn’t know if I could be that lovable.” Yet she gave birth to the most feared and violent London criminals of their time, twins who brought professional street violence to a city where the policemen didn’t carry guns.

Whitelaw smiled. “They always claimed that they only slashed, beat up and tortured their own – the gangs with which they were constantly warring. It has been said if the Krays were around today that they would clean up the drug scene, that they would have it under control. But perhaps the price would be too high to pay.” We were talking in Whitelaw’s hotel suite in Toronto, where the film had just played in the film festival. It arrived on this continent having set box-office records in England, where the Krays are still serving the long prison sentences that brought an end to their empire.

The film is the Whitelaw’s biggest hit to date. She does most of her work on the stage, and her best-known films are probably “No Love for Johnnie” (1961), as the wife of ambitious politician Peter Finch, and “Charlie Bubbles” (1968), for which she won a British Film Award as the wife of philandering football fan Albert Finney. The central fact of her career has been her long association with the work of Samuel Beckett, the late, great, exiled Irish playwright, who chose her as the key interpreter of his work.

For Medak, the director, the film is a career high. The Hungarian-born filmmaker, long in Britain, is best known for “The Ruling Class” (1972), starring Peter O’Toole as a very, very strange aristocrat, but Medak’s career in recent years has included such unexpected material as “The Changeling” (1979) and “Zorro, the Gay Blade” (1981).

The film works so well, I think, because it creates such a disturbing tension between the evil done by the Krays and the love they basked in at home. Whitelaw’s concern that she could not make Violet lovable enough is significant; how could a woman that lovable have produced – and doted on – the Krays? “Perhaps love is blind,” she said. “Actually blind. I mean, I love my children to bits. I do, and I would fight tooth and nail like a tigress for my children. But a lot of mothers love their sons, and they don’t turn out to be psychopathic torturers. I was astonished when I saw the film at how angry I seemed to get, at how often I lost my temper, and I think it was because, as an actress, the way my love was coming out was in fiercely protecting those boys.” Do you have any theories about whether her love may have led them in the wrong direction – or were they simply bad seeds? “I’ve always thought the fact that they were twins had something to do with it. And the fact that one of the twins was a psychopath had a hell of a lot to do with it. There’s no question that both of those boys are very bright. If Reggie had been just one little chicken to come out of that egg, instead of two, I think he would have gone through the usual East End working-class pilfering – the bit of wheeling and dealing that goes on in all working-class areas – but he would have gone through that, and came out the other side. But Ronnie is a psychopath. And because of that, he had enormous influence on Reggie.

“It’s sad,” Whitelaw said, “if you are going to feel sad about these men at all, that Ronnie, who was the one who instigated all these things, is kept in a hospital. He’s kept under sedation, so he’s quite happy. He’s getting happy pills all the time, and he’s allowed to see people within reason, whenever he wants to, and he sits in a room, and they have coffee and talk. But Reggie, who was the sane one, was put in an ordinary hard-core prison situation, and is now the one who is acutely depressed. He is the one who now has great emotional and mental problems.” And Violet sleeps beneath a huge marble stone that says, “Mother.”

I can only bow to Mr. Ebert´s wonderful writing and concur wholeheartedly with his observations. However, every time I watch the film, The Krays, I am somehow in thrall of the performances by Martin and Gary Kemp. They portray both a sibling loyalty and a sibling rivalry that runs in parallel and Billie Whitelaw´s was perhaps the cinematic performance of her career. It seems to me that the film captures a community muted in a love-hate relationship with the twin brothers.

My colleague Tony Brady (left) delivers his own memories of that era and the locality in which he lived as young man.

Ronald “Ronnie” Kray (24 October 1933-17 March 1995) and Reginald “Reggie” Kray (24 October 1933-1 October 2000), twin brothers (right) , were perhaps two of England´s most infamous criminals, as the foremost perpetrators of organised crime in the East End of London during the 1950s and 1960s. With their gang, known as “The Firm”, the Krays were involved in murder, armed robbery, arson, protection rackets and assaults.

In the 1960s, as West End nightclub owners, the Kray twins mixed with politicians and prominent entertainers such as Diana Dors, Frank Sinatra and Judy Garland. They became celebrities themselves and were pictured by society-photographer David Bailey and were even interviewed on television.

The Krays were arrested on 8 May 1968 and convicted in 1969, as a result of the efforts of detectives led by Detective Superintendent Leonard “Nipper” Read. Each was sentenced to life imprisonment. Ronnie remained in Broadmoor Hospital until his death on 17 March 1995 from a heart attack; Reggie was released from prison on compassionate grounds in August 2000, eight and a half weeks before he died of bladder cancer.

There were two clubs on the north side of Victoria Park Square in the 1960s: The Assumption & The Repton. On Tuesday nights I helped out in the former which provided a variety of activities to teenage boys and girls. The latter club – boys only – specialised in providing boxing activities for adolescents and young men. In the Assumption you could always recognise the girlfriends of the boxers: they hardly participated and kept to themselves while waiting to be joined by their boyfriends when training finished at the Repton. I was supposed to be a bouncer if necessary, but rarely, if ever, exercised that authority, as both clubs closed about the same time at 10pm. usually noisily but peacefully.

Once a year, the Repton staged a Gala boxing evening where it show-pieced its established and rising stars. The East End – upper and lower – society en toute patronised this event. A regular attender at Assumption and a nephew of the Repton’s Warden invited me to be his guest and the following week – although not at all keen on boxing – I went along. It was a fine Autumn evening as I closed up the club and stepped out of the Augustinian Priory where The Assumption youth club was situated. The lights from the rear of The Museum of Childhood glowed through a fine evening mist and glinted on the metal gates of the closed green space that was bounded by Paradise Row, Bethnal Green Tube Station and the Church of St. John on Bethnal Green.

Inside the Repton I was soon spotted by the Warden, George Layton, and he formally introduced me to the members of the Committee seated at his corner table: “Tony, I would like you to meet the Chairman; may I have the pleasure of introducing the Club Secretary; can I acquaint you with our Head Trainer?” and so on. Through the tobacco and cigar smoke I could barely see the other guests indicated in the official programme: principal cup and purse sponsors seated at the other raised corner tables who, with the packed standing room only crowd, watched the ring. It being the Interval, the youngest trained boxers – slim white vested, baggy shorted – and none-contenders on the gala bill – entertained the crowd with sparring feints and punching their weight into the padded fists of their trainers.

Presently, George, signalling to a short, heavily built man nearby, said I should meet two ex-members who were present. He exchanged a few words with the man whose face I could see showed much evidence of boxing experience. Whenever I see the character Odd-Job in the James Bond film – Goldfinger – I am reminded of him: squat build, bow-tied, oriental in appearance, mainly because of the punches to the eyes he had taken at boxing to the highest level. These would have been in regular York Hall appearances: a nearby venue where the East End boxing professionals contended. “Odd-Job” silently indicated that I follow him. He made no effort to negotiate his way to a corner table; the crowd seemed to part instantly at his presence until he was approached by another bow-tied and similarly obvious pugilist. They exchanged words, which in the general hubbub, I heard as “catholic club“, “geezer“, “no trouble,” “Yeah! Right!”

With one escort now before me and another at my elbow I soon arrived at a table at which six men were sitting. The nearest was watching the young boys in the ring and seemed to be moving his body in unison with their movements. We waited as he would not be distracted. Then the leading escort leaned over and said: “Ronnie, Reggie, this is Tony. Ee’s aw’right!” A voice at my elbow, Odd-Job’s, emphasized “Yer, geneleman!” I shook hands with Ronnie who stared past me immediately towards the ring. Next, I shook Reggie’s outstretched hand. “George” he said indicating a man beside him wearing a fedora hat who proffered his hand which I shook. Then a voice boomed “Boothby” as greeting, and we shook hands. At this point, a bell sounded the end of the Interval and a fanfare announced the next bout on the bill. There being no spare space at the table “Odd-Job” efficiently led me back to my original place.

As the evening progressed my table set filled me in on the characters I had been introduced to. My escorts were indeed professional boxers having come through the Repton stable. Ronald and Reginald Kray were also ex-Repton members of the club, having learned boxing there as boys and in their teens. Later, they were to be infamous as the gangster Kray Twins. At that time they loved gangster movies. “George” was George Raft – a famous Hollywood actor who played gangster roles. In contrast to the likes of James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson, actors in the same genre, Raft never knocked his women – Molls – about and acted the part of a gentleman killer. As the announcer intoned “My Lord, Ladies and Gentleman!” few present guessed it was Lord Boothby sitting with the Krays.

All of these personalities presented prizes as the bouts were fought through the different weights. The “purse” was largely raised by paying members of the public and added to by the distinguished guests. All monies raised went to paying the running expenses of the Repton which, in its day, was the premier boy’s boxing club in London’s East End. The Club was founded in-the 19th Century and promoted by Repton Public School in Northamptonshire. During the long summer breaks boys and masters lived in the impoverished East End. Working as social missionaries they fostered what was to be called “muscular Christianity” through clean living, godliness and teaching the noble art of boxing.

Various Public Schools also set up Missions in The East End. At the venue (left) for that Gala Night were bouts between members of Boy’s Clubs such as Eton Manor Hackney, Hailybury Stepney, Oxford and Cambridge House were other University Settlements in the area. Young, rough, tough and uncouth boys and young men became gentlemen and fought within the Marquis of Queensbury Rules.

Many years have passed since that evening encounter with The Kray Twins. They have become a distinct part of London’s East End criminal folk-lore. I have heard that comparisons and contrasts are made between The Krays and today’s villains in which the Twins are cast in favourable terms. That they loved their mother and were kind to old ladies are sentiments expressed in the common currency of cockney clichés. As by chance, I happened to be presented to them, I am particularly intrigued by resonances in the observation:

“The Krays! Real Gentlemen! They never killed anyone without being introduced to them first!”

The boxing scene in those days, that Tony describes, was deceptively glamorous with British champions becoming more familiar to the general public as television coverage grew. Names that stand out to me. if my memory´s chronology plays me true, are Terry Downes, Alan Minter, and Chris Finnegan.

It all seemed to have a glamour attached to it, but of course the truth was perhaps slightly seedy and occasionally very dangerous. John Richard Owens (7 January 1956 – 4 November 1980) was a Welsh professional boxer who fought under the name Johnny Owen. His seemingly fragile appearance earned him many epithets, including the “Merthyr Matchstick” and the “Bionic Bantam”. He began boxing at the age of eight and undertook a long amateur career, competing in more than 120 fights and representing Wales in competitions. He turned professional in September 1976 at the age of 20, winning his debut bout against George Sutton. Owen beat Sutton again in his sixth professional fight to win his first title, the vacant bantamweight title in the Welsh Area.

Owen challenged for the British bantamweight title in his tenth professional fight in 1977. He defeated champion Paddy Maguire in the eleventh round to win the title, becoming the first Welshman in more than 60 years to hold the belt. Owen recorded five further victories, including a defence of his British title against Wayne Evans, before meeting Paul Ferreri for the Commonwealth bantamweight title. He defeated the experienced Australian on points to claim the Commonwealth title and challenged Juan Francisco Rodríguez for the European title four months later. The fight in Almería, Spain, was shrouded in controversy and Owen suffered his first defeat in a highly contentious decision.

Owen went on to win seven consecutive bouts within a year to re-challenge Rodríguez in February 1980. He avenged his earlier defeat by beating Rodríguez on points to win the European title. He challenged World Boxing Council (WBC) champion Lupe Pintor for his world bantamweight title on 19 September 1980, losing the contest by way of a twelfth round knockout after being knocked down for the third time. Owen left the ring on a stretcher and never regained consciousness. He fell into a coma and died seven weeks later in a Los Angeles hospital at the age of 24.

Owen possessed a professional career record of 25 wins (11 by knockout), 1 draw and 2 defeats. His only career losses came against Rodríguez and Pintor. He remains revered in the South Wales Valleys where he was raised, particularly in his hometown of Merthyr Tydfil where a statue commemorating his life and career was unveiled in 2002.

Tony Brady is also describing a London that the pop songs of the day would suggest was a part of how

England swings like a pendulum do,

with bobbies on bicycles, two by two

at Westminster Abbey and The Tower Of Big Ben

there are rosy red cheeks on the little children

(as recorded by Roger Miller).

It was still the city of Noel Coward´s London Pride that´s been handed down to us, a flower that´s free, and there are coster barrows, the vegetables and the fruit piled high, and the little London sparrows.

The song even goes on to predict the inability of the police to prevent the carnage the Krays created.

When the day is dawning,

See the policeman yawning

On his lonely beat.Gay lady,

Mayfair in the morning,

Hear your footsteps echo

In the empty street.

Early rain,

And the pavement’s glistening,

All Park Lane

In a shimmering gown.

Nothing ever could break or harm

The charm

Of London Town.

In our city, darkened now,

Street and square and crescent,

We can feel our living past

In our shadowed present.

Ghosts beside our starlit Thames

Who lived and loved and died

Keep throughout the ages

London Pride.

So wrote Noel Coward, in 1941 (left) , surely the Paul McCartney of his generation, in a song that predated, by only a quarter of a century, Ralph McTell´s song suggesting sympathy for the increasing numbers of homeless people sleeping on The Streets Of London.

Others in the sixties preferred those streets lit by a Waterloo Sunset as described by Ray Davis Of The Kinks. It is interesting, though, that even that song, about a suburban idyll, was told from the perspective of a character who never stepped outside his bedsit.

Another film interpretation of The Krays, Legend (left), was released in 2015 as a French-British crime thriller film written and directed by Brian Helgeland. It is adapted from John Pearson’s book The Profession of Violence: The Rise and Fall of the Kray Twins, which deals with the rise and fall of the Kray twins; the relationship that bound them together, and charts their gruesome career to their downfall and imprisonment for life in 1969.

This is Helgeland’s fifth feature film. Tom Hardy, Emily Browning (who acts as a narrator from beyond the grave), David Thewlis and Christopher Eccleston star with Chazz Palminteri, Paul Bettany, Colin Morgan, Tara Fitzgerald and Taron Egerton as well as singer Duffy featured in supporting roles.

The plot reminds us that In the sixties , Reggie Kray is a former boxer who has become an important part of the criminal underground in London. At the start of the film, his twin brother Ron is locked up in a psychiatric hospital for insanity and paranoid schizophrenia. Reggie uses threats to obtain the premature release of his brother, who is rapidly discharged from hospital. The two brothers unite their efforts to control a large part of London’s criminal underworld. One of their first efforts is to muscle-in on the control of a local night club, using extortion and brutal violence.

Reggie enters into a relationship with Frances, the sister of his driver, and they ultimately marry; however, he is imprisoned for a previous criminal conviction, which he cannot evade. While Reggie is in prison, Ron’s mental problems and violence lead to severe setbacks at the nightclub. The club is almost forced to close after Ron scares away most of the customers. When Reggie is finally released from prison, the two brothers have an all-out fist fight on the first night after Reggie’s release, but they manage to partially patch things up.

The brothers are approached by Angelo Bruno of the Philadelphia crime family on behalf of Meyer Lansky and the American Mafia, to try to interest them in a crime syndicate deal. Bruno agrees to a fifty-fifty deal with Reggie to split London’s underground gambling profits in exchange for local protection from the Kray brothers. Initially, this system is highly lucrative for the Kray brothers. However, the results of Ron’s barely concealed violence continue to cause problems with Scotland Yard, who open a full investigation of the Kray brothers.

Reggie beats and rapes Frances and she leaves him. Reggie then approaches her to start afresh offering her a holiday to Ibiza. However, she is soon found dead after committing suicide with an overdose of prescription drugs. The brothers’ criminal activities continue, and they are unable to thwart the escalating Scotland Yard investigation by Detective Superintendent Leonard “Nipper” Read, who soon arrests Ron. The final scene shows a police squad breaking down the door to Reggie’s flat in order to apprehend him.

The closing captions indicate both brothers receiving criminal convictions for murder. They died five years apart, Ron from a heart attack in 1995, and Reggie from cancer in 2000.

In the film, Reggie and Frances’s eight-week marriage falls apart when he beats her up and rapes her. In real life, Frances insisted Reg was never physically violent towards her. Several friends of theirs have corroborated this. Helgeland has since said he used this scene as part of his “poetic licence.”

That might have been the same ´poetic licence´ that had once been employed to somewhat sanitise the Kray Twins not being employed to further demonise them. Whatever the truth of that, the sence was only one of several historical and biographical inaccuracies identified by film critics.

Nevertheless, on Rotten Tomatoes film site, the film holds an approval rating of 61% based on 146 reviews and an average rating of 6/10. The site’s consensus reads, “As a gangster biopic, Legend is deeply flawed, but as a showcase for Tom Hardy – in a dual role, no less – it just about lives up to its title.”

On Metacritic´the film has a score of 55 out of 100 based on 31 critics, indicating “mixed or average reviews”.

The memories of someone like writer Anthony JM Brady who actually briefly met the Kray Twins, two very similar but divergent film biographies, the musical soundtrack of the London of that era, all jazz and pop, and the somewhat bucolic writings about the East End and South Of The River were to be erased in the criminal courts and painted over by stories so violent as to be grotesque.

Fact and fiction might themselves be twins in some way but what we have seen already in this collection of scraps offers a compare and contrast between real life and the image art reflects..

Nevertheless, The delightfully titled on line site Flickering Myth (a collection of movie reviews) also reminds us that as recently as 2018 there was yet another movie released, Dead Man Walking, (see cover photo) telling another version of the story, (another flickering myth?) about London’s notorious gangsters, and according to Flickering Myths

´The story of Ronnie and Reggie Kray has been told several times over the past 50 years in books, documentaries and movies, most notably in the over-stylised The Krays movie from 1990 and the recent The Rise & Fall of The Krays from 2016 (which features cast members from this film but in different roles), but The Krays: Dead Man Walking is a little different in that it doesn’t feel the need to go over their upbringing and rise through the London underworld for the umpteenth time. Instead, writer/director Richard John Taylor assumes you are already au fait with their story and where they are at this point in their lives, the year being 1966 and the film opening with Ronnie (Nathanjohn Carter – The Rise & Fall of The Krays) and Reggie (Marc Pickering – Sleepy Hollow) sitting on a park bench discussing breaking Ronnie’s former prison buddy Frank ‘The Mad Axeman’ Mitchell (Josh Myers – World of the Dead: The Zombie Diaries) out of jail so they can celebrate Christmas together.

After the credits, Frank is free and holed up in a dingy flat in London waiting for Ronnie to visit and arrange for him to spend Christmas in the Kent countryside with the twins and their associates. However, Frank has anger management problems and is very distrusting of anybody who he comes into contact with and so it is up to Kray henchman Albert Donoghue (Chris Ellison – Buster) to placate the hulking psychopath with the help of ‘hostess’ Lisa Prescott (Rita Simons – Eastenders), who manages to keep The Mad Axeman in a manageable state, although he still insists on seeing Ronnie, who has yet to make an appearance.

Taking place over 12 days, The Krays: Dead Man Walking tells the Frank Mitchell story in a very concise way but sensibly keeps Ronnie and Reggie in the background, briefly dipping into their lives with Reggie going through his separation from his wife Frances and also touching on Ronnie’s involvement with Lord Boothby (Guy Henry – Star Wars: The Last Jedi) but these scenes feel a little shoehorned in just to remind you that this is a still a Krays film and not a Frank Mitchell one. In all honesty, it didn’t really need to delve too deeply into the twins’ lives as Josh Myers and Rita Simons do a terrific job with their roles, especially Simons who gives a career-best performance as the tough-as-nails Lisa who seems to be the only person save from Ronnie Kray who can keep Frank under control. Credit also to veteran actor Chris Ellison who has made a career out of playing underworld villains and bent coppers but gives his Albert Donaghue a bit of heart to go along with his tough-guy exterior, making his appearances on-screen more impactful and memorable than Nathanjohn Carter and Marc Pickering, who both do a good job but Ronnie and Reggie as characters in a film are in danger of becoming parodies of our public perception of them, with Ronnie as the cold and calculating psychopath and Reggie as the more sensitive, less dangerous one, as evidenced in a fairly unnecessary scene with Darren Day (Rough Cut) as an aggrieved father confronting the twins about their behaviour towards his son.

There are a few other small niggles that hamper the film slightly, namely the short running time which comes in at a fat-free 80 minutes that in any other ‘mockney geezer’ crime caper would be a blessing but here it makes the film feel a little undercooked, given that the performances are so good. For example, TV legend Leslie ‘Dirty Den’ Grantham pops up as the twins’ arch nemesis Detective Leonard ‘Nipper’ Read for one short scene, where he has an antagonistic confrontation with Reggie and then we never see him again. Yes, the story is about the Frank Mitchell incident but at this point in the Kray story the pressure was on, Read was closing in and the twins’ personal lives were becoming as complicated as their professional ones but being so economical the film doesn’t give a deeper view of the bigger picture. Also, with only a couple of main locations – the pub and the flat, both of which have minimal set dressing – and a few outdoor shots you never really get the feeling that this is supposed to be the 1960s as everyone wears suits and you don’t get to see many cars or things that would timestamp the story, except for the date appearing on a title card.

Small gripes aside, The Krays: Dead Man Walking is a gripping crime movie with a handful of central performances that give it a level of quality above most other British crime movies going straight to DVD and a raw level of brutality that normally gets glossed over when it comes to covering the Kray Twins. It does play fast and loose with a few facts for the sake of storytelling but this is a movie and is supposed to entertain, and that is exactly what it does, making it the best Kray Twins movie yet.

Hot Biscuits Jazz broadcaster and writer, Steve, Bewick, offers a stormy performance, this week, including dynamic arrangements of contemporary pop songs with the Christian Van Fields Trio, a piano led live set with Grant Russell, bass and Luke Flowers, drums. Also included is a blues piece from Mike Lunn, Derek Nash with `You Dig It` and Keith Jarrett, Of course, when you walk through the storm , there´s a golden sky, as you fly Over The Rainbow. The weather calms down with Mark Martin Trio & `cheek to cheek.` Join me 24/07 at

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!