a blur of legs and arms; TWO TONE

a blur of legs and arms; TWO TONE

the astonishing history, as explained to Norman Warwick

Two Tone began in a Coventry flat in 1979 and peaked two years later, when the Specials’ era-defining Ghost Town went to No 1 as riots blazed around a UK in recession.

The label launched The Specials (left)* and The Selecter from the current City of Culture, plus Londoners Madness, Birmingham’s the Beat and others, all to chart success, but also ended up naming an entire movement: dance crazy, sharp-suited, political, multi-racial ska-pop that reverberates to this day.

* Enjoy yourself … The Specials onstage. Photograph: Ray Stevenson / Rex Features

As a major two-tone exhibition comes to the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum in Coventry, the Guardian spoke to the people who were at the centre of a multicultural revolution.

Pete Waterman (DJ, Locarno club): Coventry had some of the first immigrants from the West Indies. We didn’t have as many racial problems as they had in Birmingham.

Trevor Evans (roadie/tour DJ, the Specials): As teenagers, us Jamaican guys drank in the same pubs as the white guys. Watched football together. It was a great city to grow up in.

Waterman: Everyone went to dances. I’d play punk next to reggae and ska: the Sex Pistols, the Upsetters then Gladstone Anderson.

Jerry Dammers (founder, the Specials, 2 Tone): Neol Davies – the white member of the Selecter – and I had played with the reggae musicians that would later be in that band. I’d written songs throughout my teens and formed the Specials to combine punk and reggae.

Neville Staple (toaster, the Specials): I heard [the Specials] in Holyhead youth club when they were the Coventry Automatics. I joined the road crew, then Jerry got me onstage and I started toasting like I had over records in the Locarno. That gave them another Jamaican rude boy element alongside Lynval [Golding, guitarist]. Jerry had the vision to bring together very different characters. Roddie [Radiation, guitarist] was a rockabilly. Horace [“Gentleman” Panter, bass] was an art teacher into jazz. Terry [Hall, singer] came from a punk band.

Waterman: I said: “He can’t sing!”, but Jerry correctly insisted that Terry had a very distinctive voice. I put them in the studio. We recorded Too Much Too Young and other tracks which would become massive hits. I told record companies: “Audiences are going nuts for them!” but the industry didn’t want to know.

Evans: We’d driven around the country crammed in a van for two years before anyone had taken notice.

Dammers: After we blagged our way on to a Clash tour I pushed the Specials to adopt more uptempo ska rhythms, matching suits and pork pie hats.

Horace Panter (bass, the Specials): Our original drummer, Silverton [Hutchinson], left because he refused to play ska. He said: “That’s music my parents listen to.” When Brad [John Bradbury] replaced him, Jerry came along with Prince Buster’s Greatest Hits and told us all: “Listen to this.”

Suggs (singer, Madness): We were in Camden, getting into vintage things like Prince Buster. Ska had been out of fashion since the 60s. Then the Specials turned up at the Hope & Anchor wearing the same clothes as us. Neville was blowing holes in the ceiling with a starting pistol. Afterwards Jerry stayed on my mum’s sofa and said: “I want to start a record label, like Motown.” I said: “That’s optimistic considering you’ve just played to 35 people in a pub.” A few months later Jerry phoned and said: “I’ve done it!”

Dammers: Neol Davies had a great disco dub instrumental, The Selecter. I said if he overdubbed a ska rhythm we could put it on the B-side of Gangsters, the first Specials single.

Neol Davies: Rough Trade pressed the single for us and we rubber stamped 5,000 copies in Jerry’s flat. After John Peel played it, Rough Trade couldn’t keep up with demand.

Dammers: I wanted 2 Tone to be semi-independent and launch other acts, so signing the label to Chrysalis let us do that. When the Selecter adopted ska rhythms and clothes I felt put out, but realised we could support each other.

The era of chart domination begins. The Specials, Madness and the Selecter appear on the same episode of Top of the Pops and a national tour is triumphant as two-tone mania sweeps the UK.

Suggs: When we played with the Specials at the Nashville [in London], there was a queue of kids who looked like we did. I thought: “Fuck me. There’s a scene happening.” We’d recorded The Prince as a demo but it was perfect for early 2 Tone. Then suddenly it was No 16 in the charts.

Pauline Black (singer, the Selecter): I wanted to portray something different to the sexist nonsense of the time. So I wore the “rude boy” look – pork pie hat, Sta-Prest trousers – but with makeup. It felt empowering. Suddenly there were “rude girls”. Parents were probably relieved their daughter wasn’t a punk with a mohican.

Suggs: There hadn’t been many multiracial bands in Britain, but suddenly there were all these bands in the Midlands and us, and white kids dancing to black music. It was an epochal moment for our culture. On the 2 Tone tour there were people like [Specials trombonist] Rico, who’d been in the Skatalites and who was 60-odd. All these different ages, colours, races … and we were kids, running around like idiots, a blur of legs, arms and adrenaline.

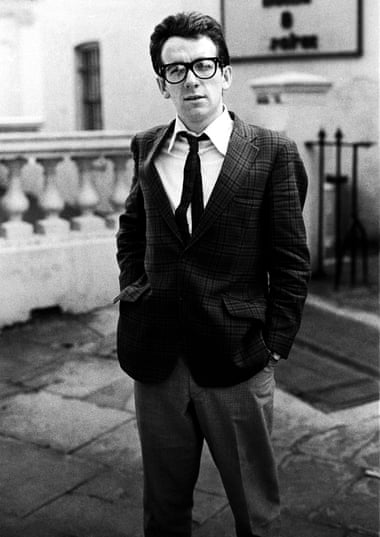

Elvis Costello (producer, the Specials): I’d travelled up and down the country – with just half a bottle of gin and some little blue pills to sustain me, if you must know – so I could see the Specials play live as much as possible before we went into the studio. I thought it was my job to learn everything I could about the band before some more technically capable producer fucked it all up and took the fun and danger out of it.

Panter: That first 2 Tone tour was 40 people on one bus for 40 nights. It was like a school trip with no teachers.

Davies: Two thousand people plus, every night. Fire limits obviously being exceeded. Such a thrill.

Costello: After one gig on the south coast we ended up on a beach with a bonfire and their fans, like a kinder version of Lord of the Flies. We recorded [the Specials] debut in a little place under a launderette. Cramped. Fetid. Ideal. There was just enough space outside the control room to jam the band and all their friends together with a beer and the lights off to do the crowd noise for Nite Klub. When Chrissie Hynde did the heavy breathing for Stupid Marriage the band were cheering like kids. We’d been at the vodka gimlets. We had to stop one session when Neville fired a blank round at me and the engineer – our ears were ringing all day.

Black: People had sent demo tapes from all over the country, so we’d play them on the bus.

Everett Morton (drummer, the Beat): 2 Tone saw us supporting the Selecter and put out Tears of a Clown, our first hit. Even after we signed to a major label, we were called a 2 Tone band. We were naturally multiracial. Ranking Roger [vocals/toasting] had been one of the first black punks. I was a reggae drummer but played faster: punky-reggae. Saxa [Lionel Martin, saxophone] was Jamaican, much older than us. The music brought everyone together.

Rhoda Dakar, (right)) (singer, the Bodysnatchers, the Special AKA): Punk had opened the doors for all-girl bands like us. The energy levels on those tours was insane. The Specials would get the audience on stage. Venues just weren’t built for that many people jumping. At one gig on a pier I looked down and I could see the sea beneath the floor. Afterwards there’d be schoolgirl pranks like apple pie beds and water pistols. I was 20. Miranda [Joyce, saxophone] was 16.

Suggs: We realised it could be fun and serious. We all agreed we were anti-authoritarian, but we’d work the politics out afterwards.

With the label’s black and white checks symbolising racial unity, the scene confronts nationalism and racism in songs, at gigs and in person.

Dammers: The racist National Front (NF) were on the rise and Rock Against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League were counteracting them. I wrote specifically anti-racist lyrics for Doesn’t Make It Alright. The black and white checks in the 2 Tone label were retro but I was pleased when people saw it as a symbol of racial unity.

Suggs: It was a heavy time. Margaret Thatcher was talking about the demise of “society” and the white working class were divided between left and right. At some early gigs our audience were sieg heil-ing.

Dakar: In Middlesbrough the band asked: “Why come to see us if you hate black people? Have you not seen Rhoda?” They went: “Yeah, but she’s a tart [a woman].” They smashed our van. We had to get a police escort out of there.

Dammers: The Specials played hundreds of gigs and the vast majority were joyful celebrations. I can remember the very few that weren’t because I hated any trouble so much. In Hatfield a brick went through the window of our coach and we had to drive back to Coventry with snow blowing in. The number of incidents of Nazi salutes at Specials gigs gets exaggerated. I can remember three, two involving one person and one involving three or four people, who we chased out. We’d stop playing, and the perpetrators were either humiliated into stopping or ejected.

Black: If you asked the audience: “Do you want these people in here?” it was always a resounding: “No!”

Suggs: Me and Carl [Chas Smash, trumpet] came unstuck by jumping in the audience a couple of times. You’d see these kids of 14 sniffing glue with swastikas tattooed on their foreheads and think: “What have you done?” And then they’d work out that they’d actually drawn the swastika the wrong way round, so it was the Indian symbol for love, which really did their heads in. But you’d see them a year later and they’d renounced all that stuff.

Dammers: We would take our anti-racist message to kids who might be vulnerable to the NF. A lot of people over the years have told me that they might have become racists if it hadn’t been for 2 Tone.

Black: We went to America just 10 years after a black person would be hosed down for sitting at the same lunch counter as a white person. At a photo shoot in Dallas, a flatbed truck came along with white guys on the back with a baseball bat, saying: “Get those [N-word]s out of here.”

The Beat including Everett Morton (left), Saxa (with fluffy toy) and Ranking Roger (wearing hat). Photograph: Fin Costello/Redferns

Davies: If I walked into a truck stop with Pauline, the place fell silent. We hit America hard – six weeks on a bus, two shows some nights. It hit us back. Charley [Anderson, bass] threw his back out. We came back a mess. Arguments. Departures. [Radio 1’s] Mike Read refused to play Celebrate the Bullet after John Lennon was shot, so no one else played it, which ruined everything.

The scene starts to fall apart amid band squabbles and music scene shifts, but a legacy has been built that stretches from generations of global ska-punk bands to the end of apartheid.

Black: We’d made our second album for Chrysalis. I walked into the record company and staff that had been wearing black and white checks were wearing kilts. Someone played us Spandau Ballet’s Musclebound and said: “This is the future.” I thought it was a load of crap, but I knew the writing was on the wall for us then.

Suggs: (with Madness, left) We signed to Stiff, but I don’t know if it would have worked out the same for us if Jerry hadn’t given us that chance.

Madness including Chas Smash (second from left) and Suggs (third from left). Photograph: Virginia Turbett/Redferns

Panter: The Specials were crumbling making the second album [More Specials, 1980, produced by Dammers]. We divided between those who wanted to stay ska and those, obviously Jerry, who wanted to experiment. Plus, the schedule was so intense. Stimulants around. We were burning ourselves out. Jerry was furious when Neville and Lynval went out and bought BMWs. Roddy came in with a load of power pop songs and Jerry said: “These are awful. Go away and write something better.” So Roddy wrote Rat Race.

Staple: We were getting on each other’s nerves. Tax bills arriving. “Why’s he getting more money?”

Panter: When we played our last [2 Tone line-up] gig at the Carnival Against Racism in Leeds we were barely speaking. I think of Ghost Town as a triumph of will, that Jerry managed to get everyone in the same place to record it.

Dammers: I’d written it after visiting Glasgow on tour. Thatcher’s shopkeeper economics had closed vast swathes of industry. The recession and mass unemployment were so bad that people were on the streets selling household items, but the song could have been about anywhere in Britain. It was No 1 when the Fun Boy Three [Hall, Staple and Golding] told me they were leaving in the dressing room at Top of the Pops. I was in shock. Pressure and confusion led me to rush back into the studio.

Dakar: I’d written The Boiler for the Bodysnatchers. A friend had been raped in different circumstances to the song, but the lyrics reflected her fear and terror. Some idiot on Capitol Radio played it at 9am on a Saturday. Complaints flooded in. It was taken out of shops but reached No 35. Jerry fiddled with The Boiler for a year, and he did the same thing with Ghost Town. It was more than perfectionism – I think it was performance anxiety. He was worried about failing, not being the best, but to his credit, he had much more of a sense of posterity than anyone else. One day Jerry came into the rehearsal room with a chorus, “Free Nelson Mandela …” I phoned Artists Against Apartheid to get information about Mandela and came up with: “Shoes too small to fit his feet, he pleaded the cause of the ANC.”

Costello (left) [producer, Free Nelson Mandela]: The secret weapon in the Special AKA was vocalist Stan Campbell. He had a voice that the microphone loved and he looked like he’d walked off a magazine cover. But everything had apparently become so fractious by then that it should not have been a surprise when he took off just as the record was released.

Dammers: Everything was taking too long and costing too much. By the time we finally had a hit with Free Nelson Mandela, everyone had left the band. I was asked to organise a British branch of Artists Against Apartheid and the festival on Clapham Common drew a quarter of a million people. It was the proudest moment of my life. We performed the song at the Mandela concert at Wembley [1988]. By the second Wembley concert [1990], Mandela had been freed. Hopefully all the 2 Tone and anti-apartheid efforts made some sort of contribution, but there’s still so much to be done.

Tone: Lives & Legacies showed at the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, from 28 May to 12 September. The 40th anniversary half-speed master of Ghost Town is released on 4 June. The Madness docu-series Before We Was We was released on 1 May on AMC and BT TV. The Selecter’s 3CD Too Much Pressure box set is out now on Chrysalis. The current Specials and Selecter lineups tour this summer

The prime source for this article was a piece written by Dave Simpson for The Guardian.

In our occasional re-postings Sidetracks And Detours are confident that we are not only sharing with our readers excellent articles written by experts but are also pointing to informed and informative sites readers will re-visit time and again. Of course, we feel sure our readers will also return to our daily not-for-profit knowing that we seek to provide core original material whilst sometimes spotlighting the best pieces from elsewhere, as we engage with genres and practitioners along all the sidetracks & detours we take.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!