of stories and songs: MCMURTRY MADE + bits and pieces

of stories and songs: MCMURTRY MADE + bits and pieces

Norman Warwick reads Geoffrey Himes to learn more.

“I’m a fiction writer,” the younger McMurtry (left) says over the phone from his home in Lockhart, Texas to Geoffrey Himes, the kindly Curmudgeon of Paste on-line magazine “I don’t want to write about me. I’d rather make stuff up. I’m not interested in me.”

´The son doesn’t write paragraphs for the page the way his dad did´´. Geoffrey Himes tells us, ´Instead, he writes rhyming stanzas to be sung. But the work is the same: You imagine someone saying something interesting in a certain situation, and then you try to figure out who that person is, what that situation looks like, and what happens next. If you’re a novelist, the reader knows that these are fictional characters. If you’re a singer/songwriter, the listener isn’t always so understanding´.

As I read this, I´m thinking of Terry and Julie in a glorious Waterloo Sunset, or of John Prine´s Donald And Lydia which are two of my favourite long novels,..sorry, I mean two perfectly disposable three and half minute songs 1

´Kris Kristofferson (right) was my first model as a writer,” McMurtry says, “and he was a Rhodes Scholar. He wrote about characters who weren’t him. So did John Prine and Tom Waits. Some of the time it’s hard to tell, because you use the first person, but it’s still a character. If you read a book, you realize very quickly that the character is not the writer. It’s hard to get your head around that in a song, especially if the writer is singing it. Some people cover my songs and even they don’t get that. That’s just human, I guess.”

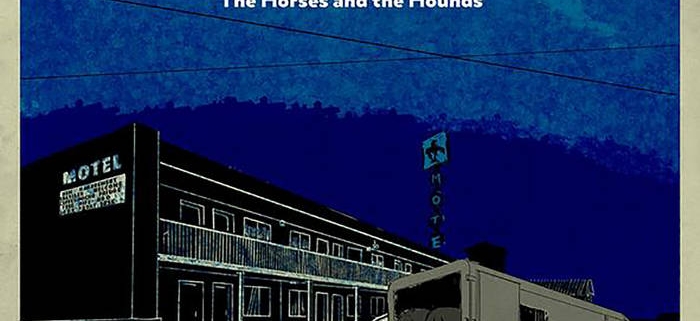

On this record, McMurtry sings in the first person as if he were an old man phoning from Canada to an old friend who had briefly been a lover; as if he were a mentally unbalanced man who shoots his best friend for no good reason; as if he were a homeless truck driver living in a series of motels; as if he were a husband with a flat tire, an angry wife and no internet. None of those characters are him, but he’s such a good actor as a singer that it’s easy to believe he is.

That’s the dilemma: He wants to be believable when he puts on a persona like a second-hand suit of clothes, but he also wants the listener to understand that the songwriter doesn’t necessarily agree with everything the narrator is saying. He wants to be able to step into the shoes of a man who would kill an old friend in a spasm of rage without being thought a murderer. If a fiction writer like Wendell Berry (left) can do that in the short story “Pray Without Ceasing,” why shouldn’t a songwriter like McMurtry do it in a song like “Decent Man”?

In fact, that song is an adaptation of that Berry story. Berry tells the story in the voice of the dead man’s daughter, who’s explaining it all to her grandson. McMurtry tells the story in the voice of the murderer, as if to address the question left unanswered by Berry: Why would someone do such a thing? The songwriter also changes the weapon of choice from a .22 pistol to a .38 to set up this description of the narrator’s haunting guilt after the shooting: “A .38 don’t kick that bad / but it kicks right through my bones every second of every day / clacking by like cobblestones under broken wheels.”

“I’ll do anything to get a song,” McMurtry explains. “I liked that Wendell Berry story, so I adapted it. I sent him a letter at his farm and asked him if he wanted a songwriting credit. He didn’t. I never would have gotten anywhere near that story without Woody Guthrie writing ‘Tom Joad.’”

Guthrie, of course, had turned John Steinbeck’s epic novel, The Grapes of Wrath (right), into the story song, “Tom Joad,” which begins with its title character getting out of prison “after four long years on a man-killing charge.” Guthrie distilled the novel from a bushel of apples to a bottle of brandy. When Steinbeck heard the result, he said, “God, that son of a bitch. He put down in 17 verses what it took me two years to write.” McMurtry does something similar with the Berry story.

In Berry’s version, the murderer’s daughter is named is Meg. McMurtry changes her name to Lola and has her visit her father in jail. She still loves her dad, despite the awful thing he’s done, and that bothers the prisoner as much as the crime itself. He had supposed the world to be a place of unrelieved meanness, and her affection shatters that assumption. “I don’t know how she even stands,” McMurtry sings, “to look on her Daddy’s face.” And the kick of the .38 shivers through him once more.

The title character of “Jackie” is McMurtry’s own invention, the cousin, perhaps, of the woman in his 2008 masterpiece “Ruby and Carlos.” Both women raise horses on the brown-grass hills of the Great Plains, trying to pay enough bills to hold onto the ranch, and finding consolation in a man too worn to marry and too sweet to dump. In the new song, the man is named Randy, and she tells him she doesn’t expect him to be faithful when she’s out on the highway driving a Freightliner tractor trailer. She only has two rules: “Don’t lie to me; don’t bring me nothing home.”

“Jackie is a very similar character to Ruby,” McMurtry agrees. “I keep trying to kill off the horse woman in my songs, but she’ll probably come back. I’ve known a number of equestrian-minded women, and they can’t quit. A guy will get busted up by a horse and get real careful. A woman will go to the hospital multiple times and keep saddling up. If your body is built for childbirth, you have pretty good resistance to pain.”

Most of the characters in The Horses and the Hounds are too old and too weathered for the infatuations and heartbreaks of young love. They still want companionship, but they know what they’re getting into. On the album’s opening track, the narrator is driving the “Canola Fields” of southern Alberta, the fields of yellow-green flowers bending in the winds off the Canadian Rockies. The color reminds him of the 1969 Volkswagen Beetle that his best friend Marie drove around San Jose four decades earlier. It was one of those friendships that had a submerged romantic subtext that erupted into the open only when they were too old to expect much of it.

“You can’t be young and have a 30-year-old crush,” McMurtry points out, “because you haven’t lived long enough. When you’re older, you don’t take things quite so seriously. You’ve seen it all before, so everything doesn’t seem like a crisis. Only then can it happen as it should.”

The album ends with the song “Blackberry Winter,” a Southern term for an unexpected cold snap in May or June, when the blackberry bushes are in bloom. McMurtry assumes the persona of a new boyfriend of an older woman, whose children have all moved away and left her with none of the activities that have always warded off the depression. And when the blues come on strong like a cold snap, she’s tempted to fill her pockets with rocks and walk into the river, like Virginia Woolf. The narrator can only “tell you no and tell you no and tell you no.” He can only offer the good cheer of the song’s bouncy, descending melodic line.

“I finished most of these songs a month before we tracked the album in the summer of 2019,” McMurtry says. “We had to book the studio time before I had the songs done. Sometimes that’s how it has to work; you have to have a deadline. You have to do your homework on the school bus like I did when I was younger.”

He recorded most of the album at Jackson Browne’s Groovemasters Studio in Los Angeles with producer Ross Hogarth, who had engineered and mixed McMurtry’s first, second and sixth albums before going on to produce albums for Ziggy Marley, Al Stewart, Lyle Lovett and Flogging Molly. The band was a mixture of L.A. studio pros and McMurtry’s pals from Austin. Hogarth and guitarist David Grissom proved so crucial to the project that they each got a co-writing credit on a different song.

“They were different songs after they changed them,” McMurtry explains. “I don’t distinguish between songwriting and arranging. If I feel like giving credit, I do. If I don’t, I don’t. Ross probably got the best vocal performances I’ve ever done. He had the best vocal rig I’ve ever encountered; it was like driving a Porsche. He’s very meticulous. I learned a lot about phrasing and arrangement, stuff that I’d known at one time but forgotten.”

A year before the sessions, McMurtry had had to move out of the house he’d been renting for 20 years in Austin. “There was no way I could afford to buy it,” he says, “but I could afford to buy down here in Lockhart. Prices in Austin have just gone through the roof; it’s not the same town it once was. I don’t know how any musicians can afford to stay there. It’s a tourist town now, and we’re the mechanical bears singing on the Splash Mountain at Disney World.”

Lockhart is a half-hour south of Austin, in the middle of cactus-and-juniper ranch country. Near the Caldwell County courthouse are several of the best barbecue restaurants in America, but the culture is very different from Austin.

“When I drive around in the country around here,” McMurtry observes, “I see a lot of Trump signs. It seems the richest people are the angriest. They have these pretty fields full of cows and antelope and a yellow sign saying ‘Don’t Tread on Me.’ I want to say, ‘Who’s treading on you? It seems you’re doing really well.’”

The most political song on the new album is “Operation Never Mind,” a description of all the desert wars of the past three decades. It’s not so much an anti-war song as a pro-working-class song. “We got an operation going on,” McMurtry sings. “It don’t have to trouble me and you / The country boys will do the fighting now that fighting’s all a country boy can do.” The private contractors for corporations like KBR run the show and get the perks, while the infantryman digs trenches and eat MREs (Meals Ready to Eat).

“I had a friend who was in the army for over 20 years,” McMurtry says. “He went in in the ’80s because he was broke. He loved it. This KRB contractor was harassing one of his soldiers, and when he confronted the guy, his commanding officer told him to stop. My friend told the officer, ‘You just lost me. This is not the army I loved.’

“My aim is not to change anything,” McMurtry adds, “but to illuminate. That song is not an anti-war song, because it’s hard to know whether the war itself is right or wrong. And for the people who are making money off war, that’s the way they like it. We don’t have Cronkite as a voice of the center anymore; we don’t have the scroll of names on the six o’clock news. I’m just trying to shine a light on it on what’s going on.”

He says he wrote “If It Don’t Bleed” for the new album “at the wheel of a van, one verse at a time.” He has to stay on the road playing live gigs to pay the bills, so he has to grab song lines wherever and whenever they occur to him. He repeats them to himself over and over so he will still remember them when he gets to the next hotel and can write them down. The result of this process is a mountain of legal pads with the newer ideas on top and the older ideas at the bottom, waiting for an archaeology dig.

“I’ve got a skinny little desk in my office,” he reveals, “where I can tape lyrics on the wall: verses on the left, choruses in the middle, bridges on the right. I don’t write down the melody because that stays in my head. The chords are intuitive once I have the melody.”

As he tries to assemble different lines into stanzas, and stanzas into satisfying wholes, he’s labouring in the family business. He’s trying to get the dialogue right, the visual descriptions right, much as his father Larry (left) did in novels such as Horseman, Pass By, The Last Picture Show and Terms of Endearment. He is most famous, of course, for Lonesome Dove, the frontier novel that was serialised as a tv Western.The form is different, but the work is the same: linking word to word to tell a story.

“I haven’t written a poem since college,” he says, “and prose fiction is a chore for me. Every once in a while, I get a page, but I don’t care enough to do all the work. With songwriting, the successful-result-per-attempt ratio is good enough to keep me doing it.”

Although he doesn’t write poetry anymore, he admits that his training in it helps his song-writing. When he went to boarding school at the Woodberry Forest School near Orange, Virginia, his English teacher was a poet named Patrick Bassett.

“His main thing was implied meaning,” McMurtry recalls.

´Patrick Bassett (left) also taught us different kinds of verse, rhyme schemes and meter schemes. I like end-line rhymes, alliteration, whatever gives it a kick. We don’t teach verse in school anymore like I was taught verse. Knowledge of poetry helps in song; it’s not the same thing, but it’s related. The main difference is that songs have to be sung, while poetry can be read. You don’t want to get tongue-tied, you don’t want to slow down the music, so you learn which consonants roll off the tongue and that makes you pick different words.”

When live music, McMurtry’s main source of income, dried up during the pandemic, he paid the mortgage by selling some of his songwriting legal pads to the Witliff Collection at Texas State University in San Marcos. The collection, which also contains papers from Larry McMurtry, Cormac McCarthy, Sam Shepard, Jerry Jeff Walker and Willie Nelson, is named after author and photographer Bill Witliff, a longtime friend of both McMurtrys. Witliff wrote the screenplays for three Nelson movies: Honeysuckle Rose, Barbarosa and Red Headed Stranger, as well as the TV mini-series based on Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove. Witliff died from a heart attack on June 9, 2019, at age 79.

“I don’t usually write songs about specific people,” McMurtry confesses, “but when I got a text that Bill had passed, I just started writing and the song came to me. A lot of the lines in the song are from Bill’s book of photos: Vaquero: Genesis of a Texas Cowboy. I spent nine months on the set of Lonesome Dove, so I was around Bill a lot.”

The then 27-year-old James McMurtry even had a role as Jimmy Rainey.

“Bill was both the screenwriter and the producer, so he had artistic control. That’s why the cattle drives are still in there. The first cut was all close-ups of Anjelica Huston. And Bill said, ‘No, we need to put the cattle back in there.’”

The younger McMurtry seems determined to put the cattle, with all their rank smells and economic consequences, back into an increasingly genteel Americana. “So pour out the coffee and piss on the fire,” he sings on “Vaquero,” the song for Witliff. “I hear hounds in the distance, it’s down to the wire / Make for the cow camp, we might have a chance.”

Two radio station outlets Sidetracks And Detours have association with are enjoying rapidly rising listening figures. We preview Steve Bewick´s programme every Monday and his choice of jazz and Hot Biscuits has been announced in the top ten of a mix cloud chart.

We now also preview The Perfect Storm on Monster Radio on 99.9 fm whenever AJ the DJ can get the information to us on time, ahead of her Monday evening show. Broadcasting out of Tias all across Europe AJ has an amazing ability to get former sixties stars from excellent groups like Prelude and later eras such as UB40. She gently interviews them live for a couple of hours from 5 to 7 pm. She recently spoke with accordionist Sharon Shannon and we spoke earlier this week on these pages of her recent interview with a microbiologist living on the island. She also even interviewed me recently and if you missed it, (and if so how dare you?) you can still read it in full in our archives under the title of The Perfect Storm

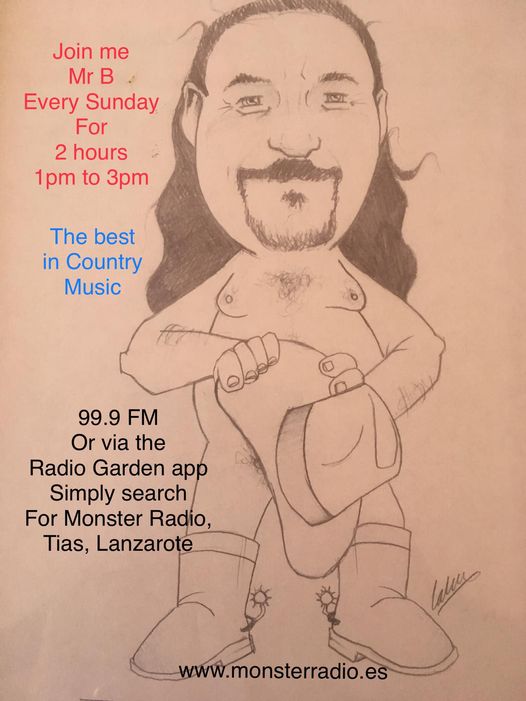

Now we can recommend another excellent show on the same station every Sunday when Mr. B (right) delivers the best in country music from 1.00 pm top 3.00 pm. You can catch it on 99.9 fm or via the Radio Garden AppTo find out Simply search for Monster radio, Tias, Lanzarote. .

www.monsterradio.es

The prime source for this article was a piece by Geoffrey Himes in Paste on line magazine. Check out the magazine on line for scores of similar thought-provoking work.

In our occasional re-postings Sidetracks And Detours are confident that we are not only sharing with our readers excellent articles written by experts but that we are also pointing to informed and informative sites readers will re-visit time and again. Of course, we feel sure our readers will also return to our daily not-for-profit blog knowing that we seek to provide core original material whilst sometimes spotlighting the best pieces from elsewhere, as we engage with new genres and practitioners along all the sidetracks & detours we take.

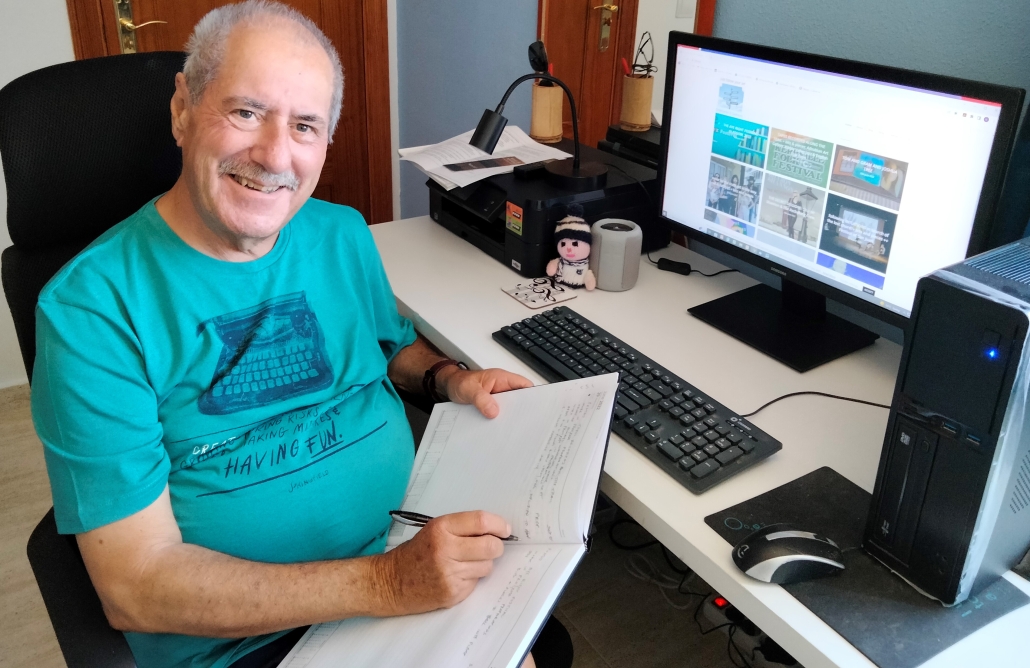

This article was collated by Norman Warwick, a weekly columnist with Lanzarote Information and owner and editor of this daily blog at Sidetracks And Detours.

Norman has also been a long serving broadcaster, co-presenting the weekly all across the arts programme on Crescent Community Radio for many years with Steve Bewick, and his own show on Sherwood Community Radio. He has been a regular guest on BBC Radio Manchester, BBC Radio Lancashire, BBC Radio Merseyside and BBC Radio Four.

As a published author and poet Norman was a founder member of Lendanear Music, with Colin Lever and Just Poets with Pam McKee, Touchstones Creative Writing Group (for which he was creative writing facilitator for a number of years) with Val Chadwick and all across the arts with Robin Parker.

From Monday to Friday, you will find a daily post here at Sidetracks And Detours and, should you be looking for good reading, over the weekend you can visit our massive but easy to navigate archives of over 500 articles.

e mail logo The purpose of this daily not-for-profit blog is to deliver news, previews, interviews and reviews from all across the arts to die-hard fans and non- traditional audiences around the world. We are therefore always delighted to receive your own articles here at Sidetracks And Detours. So if you have a favourite artist, event, or venue that you would like to tell us more about just drop a Word document attachment to me at normanwarwick55@gmail.com with a couple of appropriate photographs in a zip folder if you wish. Being a not-for-profit organisation we unfortunately cannot pay you but we will always fully attribute any pieces we publish. You therefore might also. like to include a brief autobiography and photograph of yourself in your submission.

We look forward to hearing from you.

Sidetracks And Detours is seeking to join the synergy of organisations that support the arts of whatever genre. We are therefore grateful to all those share information to reach as wide and diverse an audience as possible.

correspondents Michael Higgins

Steve Bewick

Gary Heywood Everett

Steve Cooke

Jeff Sleeman

Susana Fondon

Graham Marshall

Peter Pearson

Catherine Smith

Aj The Dj Hendry

Hot Biscuits Jazz Radio www.fc-radio.co.uk

AllMusic https://www.allmusic.com

feedspot https://www.feedspot.com/?_src=folder

Jazz In Reading https://www.jazzinreading.com

Jazziz https://www.jazziz.com

Ribble Valley Jazz & Blues https://rvjazzandblues.co.uk

Rob Adams Music That´s Going Places

Lanzarote Information https://lanzaroteinformation.co.uk

all across the arts www.allacrossthearts.co.uk

Rochdale Music Society rochdalemusicsociety.org

Lendanear www.lendanearmusic

Agenda Cultura Lanzarote

Larry Yaskiel – writer

The Lanzarote Art Gallery https://lanzaroteartgallery.com

Goodreads https://www.goodreads.

groundup music HOME | GroundUP Music

Maverick https://maverick-country.com

Joni Mitchell newsletter

passenger newsletter

paste mail ins

sheku kanneh mason newsletter

songfacts en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SongFacts

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!