day 4 of our Lendanear To Song in-print Festival: TAKE IT EASY, JACK EASY

day 4 of our Lendanear To Song in-print Festival: TAKE IT EASY, JACK EASY

Norman Warwick gathers the thoughts of others on Alan Bell.

On the death of his friend Alan Bell (left) , who died aged 84 in May 2019, Derek Schofield wrote an obituary in The Guardian of the man who was a folk singer, songwriter, festival organiser and activist, but earned his living as a sales manager in the wine trade.

´His best-known song, Bread and Fishes, written in 1968, is still widely sung in churches and schools´, Derek reminded readers, ´and was featured on television’s Songs of Praise and reached the charts in Ireland and Japan.

Alan’s first payment was a couple of bottles of beer for performing six Woody Guthrie songs in the Old Dungeon Ghyll hotel in the Lake District in the mid-1950s. He had just been demobbed after national service in Korea and the skiffle boom was under way.

hoto tavernerfs He soon turned to British folk songs and joined the Taverners quartet, who started the highly successful Blackpool folk club in 1961. They recorded four albums and did as many gigs across the north of England as their day jobs allowed, disbanding in 1981, after performing at a Royal Command Performance in Blackpool.

The son of Reginald Bell, an RAF driving instructor, and Lilian (nee Brooks), a barmaid, Alan was born in Gorton, Manchester, but grew up in Fleetwood on the Fylde coast in Lancashire, attending Hodgson secondary school in Poulton-le-Fylde.

The Fylde and the Lakes provided much of the inspiration for Alan’s songwriting. Windmills, The Lakeland Fiddler, Alice White and Song for Mardale all referred to specific people, places and incidents, and even Letters from Wilfred, about the poet Wilfred Owen, made reference to the time Owen was stationed in Fleetwood. So Here’s to You has become a standard end-of-the-night song, especially in Ireland and Scotland.

In the 70s, Alan was principal songwriter for Granada Television’s series Ballad of the North-West. Inspired by Ewan MacColl’s Radio Ballads for the BBC, he later wrote several song cycles, which were performed and recorded by his own band, often incorporating brass bands and choirs. The Band in the Park won an Italia radio prize, Wind, Sea, Sail and Sky celebrated Fleetwood’s 150th anniversary and The Century’s People told the stories of local people – local themes, but universal messages.

Frustrated that the north-west had no major folk festival, he started the Fylde festival in Fleetwood (right) in 1973. It quickly grew in size and reputation, was well integrated into the local community and recognised the area’s strong tradition of entertainment. There were clog dance and dialect competitions and a music hall night as well as concerts from many famous names in folk music.

Here he was strongly supported by his wife, Christine, who was festival secretary. Always encouraging of younger performers, he obtained Arts Council funding for Folkus folk arts network to run music workshops across the north-west. A memorial concert, planned by Alan, will take place next month.

Alan is survived by Christine (nee Harrison), whom he married in 1966, their sons, Jamie and Alistair, and his brother, Tony.

Like Derek, I and Colin Lever my song-writing partner in Lendanear, also have cause to fondly remember Alan Bell. The Houghton Weavers (left) were making recordings of Alan´s songs and playing them on the popular folk show they hosted on tv. The popularity of that group ensured that folkies in the clubs all over the country were offering renditions of songs like Bread And Fishes, and of course Alan was also much loved because he was such a genial host at Fylde Folk Festival (where Lendanear actually performed a couple of times.)

This week´s Lendanear To Song in-print Festival was to have been a Sidetracks And Detours celebration of my former folk group Lendanear but forty years after we stopped playing it has become difficult to sift fact from fiction to determine whether we actually knew, at all, what we were doing when we wrote our songs, or whether in truth we simply, occasionally and accidentally caught lightning in a jar.

Certainly after saying elsewhere on these pages this week that song-writers always seemed to me reluctant to discuss their methodology I have found, in researching Alan´s biographical items on line that he seemed to be the exception to that rule.

It was in issue 35 (December 1999) of the Living Tradition magazine that I found an article by Dave Jones in which he spoke to Alan bell, described as ´óne of the stalwarts of the British folk scene´, about Alan´s forty years of working to make folk music more accessible.

We reproduce that interview below, and will then tell a tale of the alchemy of creativity that occurred on a memorable might when Lendanear met Alan Bell in a local folk club.

Alan Bell was indoctrinated into music early in life, he remembers vividly, singing around the pianowith his father as a four year-old. But his introduction to folk music came as an 18-year-old as he cycled on youth hostelling breaks and went camping with the Scouts.

”I was in at the beginning of the folk music revival as we know it, I was 20 and just de-mobbed from National Service. I could play three chords on the guitar; [some would say that that’s all I can still play!]. I was into Woody Guthrie and sang his songs, in fact all the songs I knew were mainly American, and skiffle was the music of the day.”

It’s no surprise that the American group, The Weavers, proved to be an early inspiration, for their No.1 best seller, “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine”, topped the charts in 1952. ”In the early 60s, I stood in the wings at the Manchester Free Trade Hall, as Pete Seeger went on stage to perform his one-man show. Then followed, ”The Dust Bowl Ballads” and blues, everything was American orientated, because there was no interest in English traditional folk songs”. In those early days most of the singing was done in pubs, as Alan and his pals spent every weekend in the Lake District mountaineering, arriving by bus with battered old guitars. ”We stayed in the mountaineering club cottage in Little Langdale, I was the first club secretary back in 1955, and we sang in the Three Shires pub every Friday night. I sang mainly local hunting songs, that’s where my interest in the tradition first came from. Although I didn’t realise it at the time, Ewan McColl was on the scene down in London, along with Peggy Seeger, so there was a whole ground swell of a movement beginning.

By the same token, McColl wasn’t aware of the interest being generated in other parts of the country. “My world was very much regional, we didn’t have a broader aspect of world music. Looking back now it was very limited, very narrow, compared to how music is today. If you wanted to find a recording of a traditional English singer, it was almost impossible to do”.

The one thing Alan still derives much pleasure from today, is to hear a singer get up, with just an instrument and perform, for over-production is one of the curses of music today. ”It’s a personal hang up, somebody getting up in a corner of a pub, some people taking an interest, others not. Even if they have the worst voice in the world, at least they’re doing it their way. Folk clubs at least give that opportunity, which was the whole ethos of folk clubs in the first place, to foster singer/songwriters”.

Having found his feet as a solo performer, he wanted to get more involved. Another member of the mountaineering club, Brian Osborne, was a ballad singer performing around the Working Men’s Clubs in Blackpool. They were invited to sing one night in a pub called the Cartford, ”and that’s where we heard about a big bloke called, Pete Rodger, who was about to open a folk club, Geoff Gleave was there and they were doing American stuff, with Stuart Robinson playing banjo. They were called the Taverners Three and Brian and I made it the Taverners Five, and that was the start of Blackpool Folk Club. Jeff Cleave left shortly afterwards, when he finished college and we became The Taverners Folk Group”.

Their popularity grew throughout the network of folk clubs springing up countrywide, and they could have been out performing every night of the week. They rationed their output to three maybe four nights a week, because they were all in full time employment, with young families to support.

It proved to be a welcome extra source of income, although compared with today, they didn’t earn very much at all, but they had a great time. Did they ever consider turning professional? ”There was discussion at the time, it was the 60s and we watched other professional groups, The Ian Campbell folk Group, being a case in point. They looked like they would make it, but never did, in the sense of making lots of money and a handsome living from it. Only the Spinners, who went totally professional, took the music and presented it the way they did, were really successful. But we had no regrets”.

The Taverners were together for 20 years, and during that time did literally thousands of gigs. The group was a vehicle for Alan’s songs, so was that when the song-writing bug really bit? ”The whole song-writing thing came along as we tried to collect traditional songs about the Fylde coast. In the 60s the Fylde coast was relatively new, there was nothing there before 1750, except a couple of fishing villages, and there remained nothing much until the area was developed for holidays and the population grew. No songs could be found, so in a fit of desperation, I started writing. I’d written a couple of things prior to that, because I wanted to try my hand at it, but really the start of the Fylde songs came in the early 60’s, when I wrote ‘Blowing Sands’ and ‘The Packman’ about a travelling man on the Fylde coast. It seemed to spark something off, with other groups beginning to write their own contemporary songs, to add to the traditional ones around at that time”.

Alan’s songs have been covered by myriad artists the world over, so does he find it easy to write his songs? ”To this day I don’t find it easy, I go around with an idea for a long time, then brood about it, before eventually getting round to writing it down, or singing it into a tape and then finding a key on the piano. I don’t write with an instrument, I write in my head, which is where I get the melody line, usually sparked by the lyric.”

“Curiously, I write better when I’m working on two songs at once, because when I get stuck with one I go to the other, and continue backwards and forwards until I’ve finished both of them. A couple of years ago I didn’t write for two years, because my mind was elsewhere with work and being made redundant. With the Fylde Folk Festival dominating my life, I was so busy that writing took a back seat. I had no time at all to think of other things, no free time in my head to write. When that went away I came back with a surge and a great batch of new songs.”

“The easiest song I ever wrote was ‘Bread & Fishes’. It was a Wednesday afternoon, I had the idea and the tune, I’d been doing some paperwork and began singing the song, and I jotted it down and finished it in about two hours. I sang it at the club on the following Tuesday, it went down all right, but was a bit long, so I cut it down and suddenly many other artists were singing it too. I’ve heard it introduced many times as a traditional song, the Irish call it ‘The Wind In The Willows’, and insist it’s traditional Irish, but I take it as a great compliment. My writing style isn’t spontaneous, more like a dog worrying over a bone, trying to get everything just right.”

“In fact, writing under pressure is much better for me. Woody Guthrie had Pete Seeger staying with him in the then late 30s. Woody had a contract to write a song, Seeger went to bed, leaving Woody with a packet of cigarettes and a bottle of bourbon, when he got up next morning Woody had written, ‘This Land Is Your Land’. I’ve always admired Woody as a writer, not particularly as a person, but his songs were fantastic. Ewan McColl was also a great influence as I mentioned earlier, I knew him and listened to the first of his ‘Radio Ballads’ on the old Home Service in 1958, and in truth, that really triggered things off for me as a writer”.

In many ways parallels can be drawn between Bell and McColl, with the suites, ‘The Band In The Park’ and ‘Wind, Sail, Sea & Sky’, showing similarities to those ‘Radio Ballads’.

”It was his style of writing that caught my imagination and led me to find my own style of interpreting things. I like a good tune, and that fact alone helps people to pick it up and sing it, that’s followed by a strong lyric, with the content saying exactly what you want it to about a given subject, person or event”.

Apart from his writing and singing, Alan is synonymous with the Fylde Folk Festival, the germ of an idea for the festival came during a walk in 1971. ”It started in the pub in Cartford I mentioned earlier. A crowd would congregate on Sunday mornings, the talk got round to what on earth they could do during the summer. Let’s swim down the River Wyre was one suggestion, but someone said they couldn’t swim, let’s go by canoe then, but that was discounted for the same reason as the first suggestion. So a walk was planned following the course of the river, raising money as they went for Fleetwood Lifeboat. A bus load of people took part, and walked it over two days. We camped overnight in Garstang, having a singaround, before arriving in Fleetwood on Sunday morning. The Garstang Morris Men danced and we had a big sing in the North Euston Hotel.

It went down so well that we planned a one-day festival for 1972. I persuaded artists I knew to come for a ridiculous price and we ran a concert in the North Euston Hotel. We put on some activities for children in the morning, a concert in the afternoon, followed by another one in the evening. It was really quite good and grew so much that within three years the North Euston couldn’t cope with the numbers. I then took the gamble of booking the Marine Hall, which was in a really tatty state, but within two years, Wyre Borough Council realised that by putting on some good ale and refurbishing the hall, they could turn it into an attractive entertainment venue”.

Back in 1972, there were a few festivals up and down the country, with Sidmouth being the most famous. It was run then by the EFDSS, it was a dance festival, with music being introduced more recently. Planning is surely the key to any successful festival. ”Here we are in October, already the rooms are booked for 2000, the Marine Hall is booked ahead for 2001, while all the magazine listings are in place. The books go to the accountant this month, and he tells me how much I’ve got to spend! I then put my presentation to the committee in early November, telling them the budget and plans for next year. We set the ticket prices, and that in turn determines how much can be spent on artists and the structure of the weekends contents. We work at Fylde on a ‘bums on seats’ basis, with little or no grants, the battle is always to balance the books”.

1973 saw the first Fylde Festival, with the celebration of the 28th in 2000, so has a sound legacy been left? ”I hope so, the biggest problem is finding somebody to take it on, in the same enthusiastic way as myself and my wife, Christine, (who’s the festival secretary,) have done. Perhaps not everyone is as altruistic as we are for the music. At Fylde, we don’t shut the general public out; we take the events out to the public, into the hotels, pubs and bars, so everyone can enjoy it. It’s just as much a community event as well as for the dedicated folkies”.

When it started the festival embraced the town, but now the town embraces the festival. ”It’s a huge spin off for the town, not just the festival-goers who turn up at concerts, but commercially it’s good. Folk music is doing something for the community in its own particular way. We’ve also tried to be catholic in our taste with the music, across the whole spectrum, especially with young people. It’s thanks to people like Rusty & Stu Wright, who started working with the youngsters 15 years ago, that we have a whole generation of young performers, some of whom have gone on to national and international success. Seeing people like, Kate Rusby (left) progress gives me real pleasure, knowing they started out at Fylde. I spotted Show of Hands’ immense talent, as well as giving a young Kathryn Tickell her chance and the Battlefield Band their first gig in England”.

Away from the festival, Alan continues to write, so what’s in the pipeline? ”The Lancashire Folk Arts Network, is a new idea to try and create in the North West, using Folkworks as a model, new writing based on traditional music, both song and dance with beginners workshops. There’s no money yet, but we’ve had recognition from the Arts Council that there’s need for such an agency. I’m tasked now with writing a business plan to get things underway. I’ve also been approached to try and put something together for the Millennium, so I’m trying to write a piece that will include children, a local brass band, the Fleetwood Choral Society as well as some folkies! The brain is inert at the moment, but is likely to slip into gear any time. I also want to do a series of concerts next year, as well as recording a new CD of my Lakeland songs. For the last fifteen years I’ve been writing a folk opera on and off, which I hope to complete soon. The trouble is there’s never enough time”.

Whenever I look at Alan during the festival weekend, he looks like he’s got the cares of the world on his shoulders, which I suppose in some ways is understandable, but does he really enjoy the fruits of his labours? ”I enjoy the music, I sit at the side of the stage, and get real satisfaction from putting the festival on. From a blank piece of paper in October to the following September, when there are 18 venues and 3 days of sessions from 240 artists, that’s where I derive my pleasure”.

He may work hard, but he also plays hard as well. He has to make do with fell walking these days, rather than his first love climbing. Whilst skiing is still high up on the agenda, he still has a license to teach, which he does, in the Highlands of Scotland every year as well as in Italy. This winter will herald his 45th on the slopes.

Alan is the first to pay tribute to his family, his wife Christine and sons, Jamie and Alastair, being owed a great debt of gratitude for their love and work over the years. Alan Bell was 65 years young earlier this year, and continues to work as hard, if not harder, than men half his age, and he reckons he hasn’t met a dozen people he dislikes during that lifetime.

He has given so much to the cause that has been his life, and so many have so much to thank him for.The above section of this article was written by Dave Jones

All week we have been looking back on the forty years of work Colin and I, as Lendanear, have undertaken on a body of songs we created in the seventies. They never amounted to much, these songs, in any commercial sense but they have provided storylines, characters and memories that have seem them re-employed as articles, novels, poems, speeches, lesson plans, plays, daily blogs and now as a script for a comedy series intended for radio. Lendanear´s songs have never really provided us with an income but they have provided us with a constant supply of work.

They have provided us with moments of tenderness and terror, sometimes simultaneously.

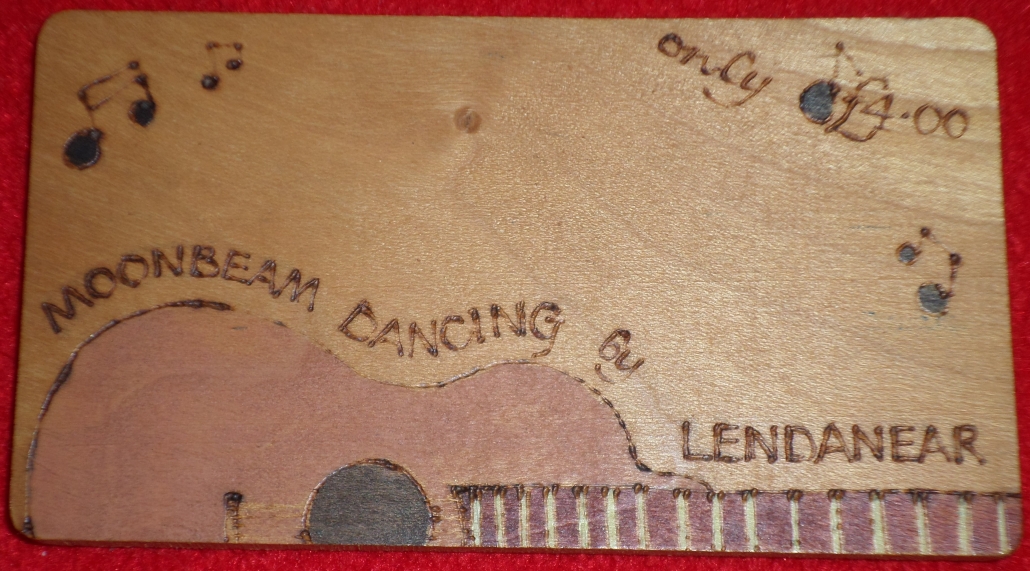

We have spoken already about some of the songs we recorded on our first album Moonbeam Dancing, but there is another song on there that came to think more deeply about this magical world of creativity we had become involved in without quite knowing how.

Just before going into the studio I had read an obituary in Don Frame´s folk column in The Manchester Evening News about a concertina player called Joe Maley (right) . Don´s heartfelt piece derscribed how the musician was based on the North West coast of the UK around the Fylde area and had regularly played the Fylde Folk Festival. As Colin and I had appeared at that Festival earlier in the year, I read on and learned that this musicians had over the years become known as Jack Easy because of his relaxed style of play,….and that was a name I felt was just begging to be put into song.

I wrote the lyrics for Easy Jack Easy over the next couple of weeks and then learned that a squeeze box played by Maley had been donated by his family to a fold group called Jolly Jack (left) who were the resident act at one of our local clubs, The Wagon in Milnrow.

Colin put a tune to my words within a few days and said we should consider it for the album. As we never thought a song was ´finished´ until we had sung it a club (and then it was well and truly finished, good and proper !) we took it to The Wagon, thinking that the audience and organisers there might at least have some interest in its subject matter.

It was actually our first appearance at that club, which my sometimes mischievous memory tells me was a small, dark room with an engaged audience and a lively and friendly resident group in Jolly Jack. If I had to categorise its ambience I would say that most of the material was more traditional in topic and style than was Lendanear´s stuff but we felt comfortable when got up to perform three of our own songs. This audience had never heard our songs but picked up easily on Fishes And Coal which we picked because of its themes of poverty and hardship, staple diets in many folk clubs. I´m pretty sure we also sang Just Listen Don´t Talk, another new song that would be recorded on Moonbeam Dancing.

The we introduced our third number.

¨We wrote this song about a concertina player called Joe Maley after reading his obituary in The Manchester Evening News. He became known as Jack Easy and I wasn´t going to let that name go without a song. This is for him,…..´

We moved into our first verse of

When the day is calm and clear and sun drop diamonds down the coast,´

listen close, you´ll hear Jack Easy´s ghost

and you will hear the wind whisper rumours of romance

and ask you for your time to just watch the day dance,….

and then into a chorus

take it easy, Jack Easy, take it easy and slow

for you shall have music wherever you go,…..

The Wagon Inn (left) audience had sung along and we sat down to a good round of applause feeling pretty pleased with ourselves, having felt a great recepti0on for two songs scheduled for our new album

As we took our seats back among the audience, the compere from Jolly Jack referenced the fact that his band had ínherited´one of Jack Easy´s squeeze-boxes and what a coincidence it was that we had sung the song tonight, with the next guest being the famous songwriter and folk festival organiser: Alan Bell,…..

We were shrinking into our seats as perhaps one of the most famous, and certainly one of the most prolific and productive folk artists on the scene took to the microphone. Although we had played by then in one of his festivals we had never actually met Alan, and I in particular was terrified he would be annoyed by my perceived audacity in presuming to write ´about´ somebody I didn´t even know.

Alan spoke into the microphone.

´I was privileged to know Joe Maley as Jack Easy and to hear him play his music live. He was loved everywhere he played and on the Fylde coast, where he lived he was a much loved character. I have brought my own tribute to him in a new song to play for the first time tonight,….´

By that time I was already mentally heading for the door, but then heard his next sentence.

´I am delighted to know that there other people already writing songs about him. That is how we songwriters make legend,….

That sentence in itself spoke of the alchemy of creativity we have been discussing all week, and I was thrilled to think Colin and I were seen as at least part of that.´

´… so I would like to sing my new song, too. It´s called The Entertainer; The Concertina Man.´

It was wonderful. It was a warm tribute to man to whom it was obvious by the lyrics Alan had been very close. It had patently been created, shaped, revised, painted over and had every flaw removed by a master craftsman.

Nevertheless, a song written by two guys who could never quite articulate our methodology had stood for a couple of minutes next to a song by a much more knowing writer. The songs were chalk and cheese and the gulf in technique between them was wide indeed. Nevertheless, whilst we´re sure that The Entertainer: The Concertina Man by Alan Bell did much to perpetuate the legacy of Joe Maley we would like to think that our song over the years bearing his nickname of Jack Easy in its title might have attracted a few new fans to the Jack Easy story,

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!