FROM PIGS TO POETRY AND LITERATURE

FROM PIGS TO POETRY AND LITERATURE

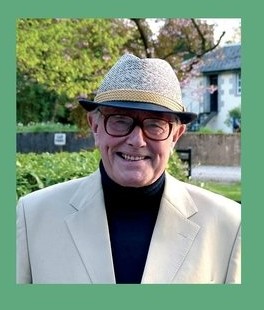

Norman Warwick learns of the life of writer Anthony JM Brady

Because your books are published in chronological order, and there are already several of them, I was slightly surprised that you refer to them as memoirs. Did you set out to write in that genre, and if so, why? Was it the genre you felt most pliable to tell your life story? Did you want to write your life story in a way that you would be able to compare and contrast with the stories of others?

That´s a marvellous question and a key one, I think. It was because IO was brought up in an orphanage of about 150 boys. Later in life there were, and still are annual reunions, and there was a common of experience of talking about our days at the orphanage and again and again over the years chums would say to me, Tony, why don´t you write down these stories you are telling us and include what we tell you as well?

And that´s what started it. My first book was called Of What Is Past and was an attempt to cathartise my experience, which had been in many ways, cruel. The orphanage was repressive and as, I say, it was cruel because even if you escaped the superiors, the staff, you would still be bullied by the bigger and older boys. In some ways, in later life, my former schoolmates and I put all that to one side and, because so many funny things happened, we treated our time there as a bit of a joke.

Many a time at these re-unions, though, the conversation would get round to what had become and remains this ´compensation society´ of our times. We used to joke that we could probably get loads of money and that she would find out how we might be best placed to do so. We kicked ideas about, and there was one chum, who lives in Australia now but who will be coming to our re-union next year, who even suggested that we could even argue that we were denied breast-feeding, so I decided to follow what avenues I could to see whether I could get these stories out there in a book form. Because the first book seemed so ´fantastical´ friends then started to say to me that all the stories it contained surely couldn´t be true, I then sent the draft to twelve people and asked them their opinion because some of the stories of the cruelty that took place seemed to require verification, so I approached those who I felt we would be able to comment on that and their memories of it and whether or not their memories resonated with mine. I then took their comments, and applied them almost ad hoc as the epilogue to Of What Is Past, and then set about, effectively to write a book addressing each of themes raised in their comments, and on which I have tried to impose an accurate chronology.

That methodology is fascinating and the way fact was turned to story and then back into fact leads to a fascinating question, for any writer, I think, of whether you have created this work or this work has created you?

Oh, another interesting question, yes. In other words, is it memory – clear, factual memory – or is it what a psychologist would say, a recovered memory, which is often, it feels somewhat embroidered to make events worse than they were originally? I can say that confidently because my daughter has a doctorate in psychology so doesn´t entirely resonate satisfactorily with me, because I was aware of the pitfalls of writing from recovered memory so when I was fifty I decided that by the time I would retire at sixty five from what was a very high-stress job I would write there and then, while my memory was good, rather than wait another fifteen years until it might not be as good as it had once been. So I can answer you by saying that I wrote that first book while my memories were still vivid and I had already been maintaining a diary since my mid-teens.

So, with that you can be sure that you have not only remembered the events correctly but can also verify their chronological order?

That´s right, through my diary and the events of that first book. One of the things I invariably asked boys at these re-unions was about the argot we all shared, a kind of secret language that superiors, nuns and others could not understand. We all had a vocabulary of terms that we as boys might use that the sisters would not necessarily understand.

I guess its true that most playgrounds in most schools have that cryptic vocabulary that is also a colourful truth of gang culture. In fact that reminds a little bit of the Edwin Waugh Society, located in my former home town in Rochdale in the UK: It is named after a dialect poet and scholar who worked in the area and his work has since generated much etymological curiosity and it has been found that in Waugh´s lifetime, not only were there several local dialect pronunciations of his surname, but that sound of hundreds of words would differ from community to community along the roads between Bury and Bolton only a few miles apart. Scores of ways of saying the word HOME have been identified. It was dialect rather than argot, obviously but I remain fascinated by what creates dialect and by what dialect creates and what factors slowly change dialect, too. It makes me wonder, though, whether your ´chums´(and there´s an example perhaps of a word slipping out of fashion, (and sounding a bit Bunter-esque perhaps) think of themselves as accessories to your work or as characters within your work?

No, I didn´t create profiles of the boys. I might have referred occasionally, tangentially, to the boys but I didn´t profile them. I did, however, draw profiles of the sisters, and of the punishment-master, as it were, who was a paedophile as well, just to clarify. That aspect, of recognition perhaps and privacy etc., has been rendered irrelevant by facebook. We have our own facebook group and nicknames and reference to certain individual personalities do come up now and again. Of course, all that is changing. I am 81 now and of course many of the chums were of similar age and so we have sadly lost swathes of our own community over the last few years. However, we did manage, nevertheless to hold our fifty sixth annual reunions this year, with last year, because of covid, being the only interruption to our annual events.

And what do you know between you of the venue of the school? Is it still there? Is it still functioning in the same capacity?

I was giving some presentations to teenage school-children in Germany one time, and as soon as I put up a slide showing the school, they all shouted Das is Hogwarts ! It was actually a beautiful mansion set in its own forest, (see left) It had a gate house and a lodge house, and then a long drive up to the mansion itself, with its stained glass windows, beautiful panelling, high ceilings and bats flying about at night time, flitting along the passageways in the chapel. There were owls hooting, foxes barking and perhaps a bit overwhelming when I arrived there, at Blaisdon Hall, at twelve years old in the early nineteen fifties.

Somehow, though, it was marvellous at the same time, even though the sisters at young school had, for years, threatened us with ´the terrors of Blaisdon Hall. There were no women at or girls at Blaisdon Hall, I soon realised, and the masters were all men. The reason for this was that the school was a place of theologian studies and for training young men for the priesthood or brotherhood, and of course celibacy was part of their commitment.

Were you aware of any attempts to channel young men into that kind of commitment, even though they might have been ´sent ‘to the Hall for more conventional academic study?

When I moved there I loved it straight-away, partly because Blaisdon Hall wasn´t particularly academic. It taught a whole range of skills for what they called ´the world of work´ so there was metal work and woodwork, but there was tailoring, too. We all learned to sew. We could all patch our clothes, darn our own socks and replace our own buttons. There was boot-making and bee-keeping, and forestry and gardening and the place was self-sustaining in many fruit and veg food stuffs. So by the time a boy was fifteen or sixteen and ready to leave he had had a set of basic skills to help him find a job, in catering for instance, as he would have learned to make butter and cheese and to bake bread and to cook at Blaisdon hall.

I wonder if there was any recognition among the pupils or the staff that this was perhaps an education aimed at a world that was rapidly disappearing, with the next couple of decades being a period of such dramatic growth and change.

The education act drafted in 1948 didn´t actually come to fruition until 1952, when I was twelve years old, a team of educationalists came to live in the school for a fortnight. There six of them, men and women, who attended meals, sat in classes and made notes all the time. They looked in the chapels and the dormitories. The school was interesting, because academic classes were only held in the mornings, with the afternoons being devoted to cadet training or specialist activities. There were detention activities in the afternoons, too, and my least favourite was when I had to weed the pathways, around the beautiful ornate gardens.

Anyway, these educationalists eventually submitted their report, but it was only years later as I started researching my books that I learned how that report had come as something of a shock and had caused something of a furore.

And perhaps that gives a clue to answer your question,….was this all an age of disappearing innocence?

Priests need to be in contact with women, the report recommended, and suggested the employment of a Matron. It also declared that Blaisdon Hall taught far too much Latin, too much religion and far too many religious ceremonies were being held. In short, the report suggested we pupils were not being saved for our bodies but for our souls. The report did compliment the sports activiti9es being taught and even said we played team sports quite well, but that we perhaps needed to play against other local schools to measure our standards ! The report also noted the starkness of the dormitories and of a certain lack of privacy, suggesting curtains should be put up to create personal space. In commenting on the poor plumbing the report noted that when taps were turned on, tadpoles came out !

So, what had funding Blaisdon hall And where would further funds come from?

I had arrived at the place having been ´saved´ by a charity called The Crusade of Rescue. It was their job to gather all those children abandoned during the war. Although I wasn´t abandoned I could add a romantic twist that added an element of abandonment. My mother was unmarried, a cardinal sin and was shamed out of her community in Ireland and came over to England. When seeking help, she learned of The Crusade of Rescue and she took me to Westminster Cathedral (right) , and this is absolutely true, I know, because I have researched it thoroughly. Apparently mother didn´t really want to give me up but she did believe that if a fine woman in a fur coat heard me squealing she might adopt me. However, priests were aware of this kind of practice and knew that if they head an infant crying but could see a woman not too far away, she didn’t really want to abandon her child. On this occasion the priest whipped back the curtain, saw my mother and began speaking to her. I learned years later that all this was commonplace in those times.

Mum explained that she had only been able find lodgings for six months but was now under an ultimatum to leave and had nowhere to go and couldn´t provide for me. The priest promised to write a letter to the landlady and provide any help the church could provide. Next day two ladies came to see mum at the loading house and one of them took me and picked me up and the other lady reassured my mother that she was neither losing nor abandoning her child and that they would look after me

They had also found mum a job and whistled her off to a posh area of London and the next twenty five years she worked in service for a Jewish family. I knew nothing of this at the time, of course. I had been through a series of orphanages before arriving at twelve years of age at Blaisdon Hall. I have since learned that I was fostered by The Crusade of Rescue to a single lady living on a farm in Chelmsford, in Essex. When my mother was eventually allowed to visit me after a year or so she complained that I wasn´t fat enough ! So, I was taken away and straight into another orphanage with around a50 children with a similar background experience to mine.

I tentatively enquired when I was around six or seven about the whereabouts of my mum and did, but the sisters at the orphanage were pretty dismissive, distracting me with tales of how my dad had died bravely in the war and was buried somewhere in France and my mu was dead too.

So, you have obviously since become aware that this was a significant, if unspoken phenomenon of the second world war,…that because of war time romances, or premature deaths of parents, there were countless single parent families who couldn´t cope. Is the purpose of your writing to romanticise what was obviously a tough period for you personally and for thousands like you, or is the purpose of the books to examine how and why all this happened and the consequences of it happening? Are there times when you are writing that you feel the need to put the brakes on because you might be romanticising the situation or alternatively if there are times when you think things might be sounding a little too dark, and that perhaps you need to apply your writing skills to lighten it and romanticise it? As a writer how much are you aware of the fact that this is a story or a creation.

A lovely question again. Even as I set out on this writing venture I was aware of the agony of being a novelist and creating literature. At the time I began drafting my first manuscript I was aware of books like Angela´s Ashes by Frank McCourt and I wanted to avoid simply adding to that list and so I went for a realism, that I knew something about from my voracious appetite for reading.

Reading in the Catholic tradition of that time was pretty restricted; so much so that there was in existence a Vatican Index Of Prohibited Books (example left) ! So, when I was a teenager my first act of rebellion was to set out to read every book that was on that list. On pain of sin, here on earth, and later in Hell.

I read widely from George Orwell to Jack London, of course.

The problem was, though, that I was striving to understand what the word family meant, as I had had no real experience of it. The first novels I read were all late eighteenth and nineteenth century works simply because I wanted to understand family life. However, to my horror, reading the novels of the Bronte’s and so on, I learned only wehat it felt like To Walk Invisible (right) and the families I encountered in those books were absolute cauldrons of hatred, intrigue and cheating. People being done out of their inheritance, women dominated and humiliated by cruel men !

Isn´t that interesting, though, because it was the late twentieth century that brought this stack of what we have chosen to call agony novels, in which we might include Kes and Cathy Come Home that later gave way to what I see as redemptive novels, like Billy Elliot, all of which in some way mirror their times. Like the Bronte novels these, too, reflected class warfare and a struggle for equality. Strangely, though, being born in 1952 I grew up reading about soli8d families, as described by Enid Blyton in The Famous Five series. Good old Uncle Quentin and Timmy The Dog.

I loved Enid Blyton, though I see those stories now as idealised. And I loved Agatha Christie, as well. Then I got very deeply into French Literature, evening reading Jean Paul Sartre (left) , before realising I just didn´t understand him. In fact I´m going through a phase in my life, or re-reading those books I couldn´t understand as a teenager. like Camus.

I´ve just gone back to Herman Hess. I loved The Glass Bead Game and although I didn’t understand it I loved his writing style, his innate wisdom, and his quest.

I didn´t realise that although I didn´t understand much of what I read in my teens I did nevertheless partake in the process of osmosis and absorbed far more than I realised at the time, and as I read I was also asking myself how can I write. What is the process? Where is my voice?

At least the priests complimented me, telling me in those learning years that my comprehension exercises were good. Creative writing exercises in the classroom would be to write a hundred words about snow you see in the garden or about the owl you hear in the woods.

So that was giving you some basic skills but when you began reading with a growing awareness that you might one day become a writer yourself, how did you assimilate and disseminate what you were reading on the page, or did you just sit back and imbibe, so to speak.

Osmosis. It just dripped out of my fingers on to the page. No problem whatsoever.

I was interested to hear that you did some reading of French Literature, too. Although I’d never heard of him until I went to university, when I was fifty years old, I became almost obsessed by the Death Of Author theory as espoused by Roland Barth. Is he someone you know, and are aware of that theory? That notion that once a text is completed our job, as a writer, is done and it is then down to others, the readers to take ownership and direct its itinerary. On completion of writing, the author ´dies´, according to Barth, no longer relevant to what he has written !

Yes, I read some of his work, and other literary theory too.

So, how do you feel on completing a text? Do you worry what might happen to your work in the hands of ´uncouth´ readers?

Ha. I wasn´t expecting that word. uncouth. The simple is that I feel right, I´ve done it, its away from me, its no longer a part of me. Its by this time just bread on the waters to me.

Do you feel cathartic in some way, having written a piece that is obviously important to you? Has it laid some ghosts to rest?

Exactly, and has made me more sympathetic and empathetic to those who gave me an education that eventually led me into my career as a social-worker. I spent the last twenty five years of my working life working with homeless people, in Central London. I´ve worked on what the Americans call Skid Row, and have worked in all the various tiers of rehabilitating. I´ve visited every prison in London in a working capacity.

I can tell you it used to raise a good laugh and a few eyebrows whenever I mentioned in any speaking engagements that I had spent the day with prostitutes ! I did in fact work, indirectly wi9th the English Collective Of Prostitutes whilst working with the London Borough of Camden for many years. In that capacity I attended several meetings with agencies such as The Salvation Army and Alcoholics Anonymous for example, and one such agency with which we met regularly was the English Collective of Prostitutes. Another was a body called PROD run by a guy called Ted Eagles (I think) who told us the acronym stood for Protections of the Rights Of Dossers! Indeed, he always introduced himself as an ex-dosser.

So all this a roundabout way of saying that my experiences at Blaisdon Hall mutated into a sincere sympathy for the underdogs in life. I became a dissenter and agitator, out for any demo in the early sixties.

Dissenter and Agitator. Are these terms we should perhaps naturally apply to a writer and artist?

They are, I think. Writers and artists so often have to fight their way through.

When I first set out as a writer, and in a field that saw me ´cavorting´ with dancers and singers and painters and poets, my dad thought I was bound for Hell. That reminds of something you said earlier about becoming a social worker. Are you aware that our poet laureate, Simon Armitage, once worked for the Probation Services?

Yes. I know Simon. I´ve communicated with him.

I mention it because I was lucky enough to be facilitated by him at The University Of Leeds, which I didn´t attend until I was fifty, three and half decades after leaving school with two CSE grade threes. Before going to uni I had looked back on a school life that hadn´t offered me any cathartic experiences, and that I perceived as an education that was wasted on me because I wasted it. By the time I reached university I just about knew how I could take what they could teach me to help me do what I wanted to do. It sounds like you learned to value your education, whatever its method of delivery, far earlier than I did, and that you have used it to inform your social-work and your writing ever since.

So where can our readers find out more about you and your series of novels?

Simply, they could just ´google´ Anthony J.M. Brady (right) I have thirteen titles published, of which the main work is the quartet (of Blaisdon Hall memoirs) and I have two collections of poetry, too, on my web site, collectively called Homage To A Teacher, which chimes with your link to Simon Arbitrage. I had no formal qualifications at all on leaving Blaisdon Hall, but at the time there was a farm attached to the premises. I got a paid job there as a farm-labourer, so my first five years of my working life were spent looking after pigs ! in that time I became the pig-stock man looking after 500 of the animals, but in an attempt to trace my father, who I believed to be in France, I signed up, to the horror of my contemporaries, to learn French down the road at the technical college. So, at the end of a working day with the pigs I would cycle ten miles over to Gloucester, to spend an evening learning French with a student base, mainly, of florid, beautiful girls with their Cheltenham-style accents. I would arrive sweating, if not stinking, because washing facilities at the farm were pretty primitive. Studying French changed my life because I learned about a doctor called Albert Schwieser who ran a Laprosium and hospital in French Equatorial Guinea at the time, and I decided I wanted to become the second Dr. Albert Schweitzer!

So now you became bi-lingual I guess, which compels me to ask if you, as a writer, think that a story is changed by the language in which it is told?

Another searching question. Yes I think so, because I have worked in translations. In fact to the shock of everybody in my Freshen class, we were set to study a poem by Rimbaud, and I translated it. I did that ion something more than just a word for substitution, which might not have worked, but actually also translated it not rhyming verse. That´s not an easy task, though this was of a fairly simple poem called, in English, The Sleeper in The Valley, in which he describes an atmosphere as does Wilfred Owen in Anthem For A Doomed Youth, but Rimbaud describes the countryside before introducing the soldier who is a reflection of the life and vivacity of that landscape, but in the final couplet he described two red holes in the soldier´s side, and we learn that the soldier is dead, and we hadn´t really expected that.

The man who was teaching us French admitted to me then, that he expected to find me the biggest challenge in his class, as I had turned up with none of the qualifications the others had. However, he praised the way I had approached the piece,.

Do you think perhaps that your approach was perhaps less rigid than that of those around you who might have appeared more qualified? Perhaps you were looking beyond linguistics and technique to the story that lay within the language.

Well I returned the compliment to my teacher and told him that honestly I would never have got anywhere without his teaching and guidance. Qaulifications aren´t everything. In fact I’m here on Lanzarote to meet with a writer, Rita Schmidt, who has written a very personal book, which I came across in a bus stop converted into a telephone box and then into a tiny book depositary, in the UK. I loved it and contacted here, and found out she now lives here in Arrecife on Lanzarote and I´ll be meeting her for the very first time as soon as this interview is over. Her book resonates resoundingly with me. It deals with loss and grieving and has made me think very deeply about those subjects.

That history of bus stops in Gloucestershire being converted into book depositories is. if you haven´t made it into one already, a story well worth telling. I look forward to reading it, and if ever you´d like to write a piece for Sidetracks & Detours I´d be really proud to carry it.

I´ll also have a look out for Rita Schmidt´s work and perhaps try to run a feature on her in the coming months. We´d also be delighted to keep our readers informed of any further titles you publish or any other news concerning your writing.

It has been a pleasure to meet you.

This, just in, from Jazz In Reading listings brings a venue were not previously aware of. The Kenton Theatre 19 New Street Henley-on-Thames RG9 2B will be presenting Steve Waterman with the Max Wright Trio on Wednesday 2 March 2022, at 8pm. Tickets are £26-00

Steve Waterman is one of the most highly regarded trumpet players on the UK jazz scene. Steve has appeared on albums “Buddy Bolden Blew It” and “Stablemates” which have received critical acclaim. Steve effortlessly blends masterful technique with lyrical improvisation to produce powerful solos. Throughout his career he has been invited to play and collaborate with numerous artists such as Chucho Valdes, Jeff Hooper, Andy Shepard, Alan Barnes and more.

Steve will be joined by The Max Wright Trio to create a new collaboration. The Max Wright trio is made up of three young and upcoming musicians from London with Ayo Vincent on piano, Pete Komor on double bass and Max Wright on drums.

Expect high energy solos and fierce interaction; this is a night not to be missed! Performance starts at 8pm, tickets £26 via the Kenton Theatre website or on the door.

Beginning on Monday 28th February we will be hosting a Festival-Inprint Of Five Women Who Shaped My Point Of View

We kick off the Festival with a look at makes Dianne Warren, one of the leading female contemporary song-writers, and we learn why Emmylou Harris has been the first name picked for Americana Festivals spanning two centuries. Not least because she and Emmylou were ´two of a kind heart, we also run a feature on Nanci Griffith, looking at when Nashville tried to make her their own.

Martha Wainwright is, of course part of the dynasty that both folk music and country music try to claim as its own, and although she may have been slightly late to the party, she fully deserves her invitation to this festival in- print.

Minnie Driver is another woman, an actress, though, rather than a musician, who has similalry refused to play corporate games. In fact she once described Hollywood as ´never a meritocracy, never a level playing field but has nevertheless arrived at when there never been a better time to be a woman in film.

So there, will be plenty to read about who make a difference. Its another free in-print festival folks. Come follow your art.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!