ELVIS, THE COSTELLO KID

ELVIS, THE COSTELLO KID

Norman Warwick listens in TO PART ONE of an interview

Interviewer Stephen Dubner began this podcast with a comprehensive overview of his subject.

´Elvis Costello, the 64-year-old singer and songwriter from England, lives in Vancouver with his wife, the jazz singer Diana Krall, and their two kids. Costello has been making records since the late 1970’s, records that range from punkish pop to super-dense super-pop to country-and-western; from earnest to sardonic. He’s particularly adept at bringing a postmodern flair to the elegant foundations of the old-school songbook. That’s what he’s done on his recent record, called Look Now.

photo 2 Just how versatile is Elvis Costello? Over the years, his collaborators have included Burt Bacharach, The Brodsky Quartet, (left) Anne Sofie von Otter, Paul McCartney, the Charles Mingus Orchestra, and Allen Toussaint. For a time, he was nearly very, very famous; to those who love his music, he’s way better than famous: he’s an original — a musician’s musician, a writer’s writer. He’s also got the rare ability to create music that is both high-minded and open-minded — and, as you’ll hear, he can do that in conversation as well´.

That said, Stephen Dubner invited Costello to the microphones.

If you would just say your name and what you do, however you’d like to describe that.

Hello, I’m Elvis Costello (left), and I am some kind of musician and a writer.

So, let’s start with your new record, which I love. Congratulations. I think it’s remarkable. It’s rich and dense, but also gritty and funny, and it’s modern and traditional, and it’s a record that no one in the world but Elvis Costello could have written.

That’s a pretty good compliment. But that’s what I hoped to do, to be really truthful. I had these songs, some of them I’d written a while ago, some of them were written in collaboration, some of them were written very recently. And I knew that they were songs that would be served by my band, but they would give us an opportunity to show everything that we can do, not just one aspect. A four-piece rock-and-roll band is often just asked to be a four-piece rock-and-roll band. And that’s great fun, but it’s also great to be able to bring to anything that which you’ve learned, that which you’ve come to understand, be able to quiet yourself to the mood of a ballad, and in this case playing in collaboration with Burt Bacharach (right). I couldn’t imagine us pulling that off 20 years ago or longer.

You write in the liner notes, “I wanted to make a record that we couldn’t have made back then.”

Yeah. To me there’s never been any point in making the previous record again. So, each one has, to my ear, been quite different. To people who don’t hear those increments change, or don’t have the same appreciation, probably all my record sounds the same. But they’re attuned to different things than I am. And the great thing is we’re totally spoiled for choice. We have so much stuff we can listen to: from the past; from the present; stuff that’s secret; stuff that’s right in the headlines. You don’t have to have one above the other. It isn’t necessarily a hierarchy.

One of the only positive things about the changes in the way music is heard is that the hierarchal aspect of it has become less oppressive. There are still people that sell massive amounts of records and people are obsessed with those achievements. But some of the most interesting things are happening in little corners. And that’s not to say, “Well, I’m making the best of it, because I used to sell records and now there aren’t records to sell.” It’s just that that’s the way it is. I find that the records that really interest me by other people — whether they’re people of my generation or whether they’re brand new artists — they tend to be things you stumble upon, and it reminds me of how wonderful it was to feel as if you had personal possession of a record that nobody else knew about, which was the way it was when I started out.

So when you were a kid, your dad was a singer for what sounds to be a pretty wonderful dance band, you call them.

Yeah, nobody would regard them as hip in the slightest way, but the leader, Joe Loss, he managed to front a band from the late 20’s to the 80’s. He was a remarkable character in English light entertainment, and he had a very good ear for two things: people, talented singers — I mean, Vera Lynn made her debut with him; my father later had good singers. And my dad had two other singing partners, and they were on the model of the Glenn Miller band. They weren’t by any means up with the rock-and-roll vibe or anything like that. But as time went on, because of the curious way radio was set up in England, the way we heard a lot of popular songs were as they were interpreted by dance bands and light music ensembles of all dimensions.There was an agreement between the BBC and the musicians’ union that there were only five hours of recorded music allowed a day.

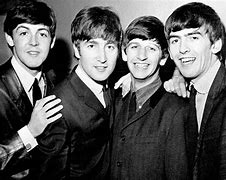

You couldn’t play recorded music for more than five hours a day. So bear in mind that there was only the BBC. There was no commercial radio in England. There was one station which we could beam in from Luxembourg which broadcast in English and played continuous pop music. But it wasn’t until the pirate stations started up in the mid-60’s that the revolution to the American model of 12- to 24-hour radio took hold in England, and therefore we heard a lot of things filtered. And that’s why you see, in archival clips, The Beatles, and very big bands like that, appearing on light entertainment shows with comedians. And they would have to get their music out somehow and the opportunities to play on television were limited to maybe one or two pop shows a week on television. I’m talking about all of recorded music, so you are dividing up the classical music, the pop music, jazz. So, there were a lot of broadcasts of live music, whether they they were bands interpreting the hits of the day, or little shows that presented people playing music for broadcast like jazz ensembles or folk singers.

I never knew that. So that’s fascinating. I wonder if you believe in retrospect that that scarcity retarded a certain kind of original British music making.

No, it had the opposite effect. I would say that the rarity of it sharpened the wits of the people that got through, although there were obviously contradictions in it. A lot of the rock-and-roll singers that were on the radio when I — because my parents didn’t really listen to rock-and-roll, they were jazz fans. Rock-and-roll seemed a bit flimsy, I have to be honest, because I never heard any of the really original exciting stuff because it didn’t get played. We heard this vanilla version of it. They were local acts that had been styled and given names to sound like American acts.

It was The Beatles (right) really that blew that up, and The Beatles came and signed to, they were turned down by the first label that they auditioned for. And then they went to Parlophone which was an E.M.I. label, but think of the name. What does it mean? It’s a talking label. It was a comedy label. I don’t think they really knew what they had. Nobody has ever said this that much, but I think they might have thought they were a novelty act initially. I’m sure the people up at the top of the company like George Martin obviously understood what they were, but I think they thought that they’re probably a one hit wonder. And people that spoke in northern English accents in those days were mostly comedians.

You’ve got to remember that we’re talking about the BBC, where they still put on evening dress dinner jackets, to read the news on the radio. I mean they’ve always had services, that broadcast in different languages, but the home broadcasting was very much two things: what they call BBC English, which was a kind of formalized English, and mostly northern English comedians, or people from a musical, who were genial hosts of things. But the idea that it would reflect real life was not really—

As a kid in the north — you were from London originally, and then when your parents split—

Yeah, we stayed in London. I grew up in the suburbs, in the western suburbs, and you wouldn’t call it London because we were out so far. And it wasn’t a bleak place at all. It was very leafy. But I spent a lot of school holidays on Merseyside. So, my dad from Birkenhead, my mother from Liverpool, I spent a lot of holidays staying at my grandmother’s house. I felt as much at home there. I was actually taken north as a baby and christened there. So, I had this feeling of belonging to both places.

It’s hard to feel you come from London because it’s such a mixture of neighbourhoods and overlays of culture. If you come from one of the old neighbourhoods, particularly in the east or the north of the town, people say “I’m North London” or “I’m East London.” West London, it gets a little bit more foggy about identity. We just live out there.

You are a musician much loved your fans and yet you’ve never been the mega-sized star that you threatened to become years ago, and I’d like to talk about that.

Well, it was threatened by other people. I made a conscious decision about the use of my time. 2010, 2011, I had an enforced little bit of time off. I released a record in 2010 which I really loved. It didn’t seem to demand that the music be played live. There was no demand for me to perform those songs, and it coincided also with my father’s passing, and maybe that just made me take stock. And I started to think that maybe records were a vanity that I shouldn’t indulge. That brought home how limited time was, and with having young children, I decided that if I was going to be away from home, I had better be really be bringing home my share of our family income.

It was a much more certain bet to go out and play concerts and I also felt that maybe I had an opportunity — now I really did have too much material for one evening of songs — that I could create shows. I ended up creating two or three shows, stage shows, I’m talking about. They weren’t elaborate productions with huge expensive values; they were cheap carnival tricks that I used to frame what I had, which is my songbook. The first one was called, “Spectacular Spinning Songbook,” it was a revival of a show I did first as a kind of dare in the mid-80’s where we used a game-show wheel to select the next song, and I had a beautiful assistant like a magician.

It was real, and I mean sometimes we rigged it towards the end of the show to get a number to get offstage. But now, we let it go as it was. It was a tremendous challenge for the band because they had to know somewhere around 150 songs at the drop of a hat. And you could get a run of three finale numbers to open the show, and then you would have to find how you could continue the mood.

Everything conceivable happened; you’d have people that would come up and we had a very good cast members. We had a dancer who was really sympathetic. She was really good, she was doing a parody of it like a go-go dancer. Some people didn’t realize the whole thing was a satire. They thought we were actually serious. The whole point of it was to bring people on the stage and invite them. You never could guess how many people really want to be a go-go dancer. And there were people on stage who should never dance that did. And that’s a great moment because I’m the worst dancer in the world, so I really have sympathy for people who come up. They threw themselves into it and we’d have mothers and sons come up and do it together, and married couples. We had a couple, one guy propose to his fiancée. I started to claim that I was actually ordained at one point. It really, it was a semi-invented character I was playing. It was partly me and partly this character I was inhabiting.

And then, well, I applied myself to finishing a book I’d been working on for 12 years called Unfaithful Music and Disappearing Ink. And I then worked up another show over a couple of tours where I gradually gathered props. Started out with an on-air light like you find in an old radio studio, like the kind I saw when I would go with my dad to the radio broadcast. And then I added a television set which had a screen onto which I could project cues to the songs; sometimes there were old advertisements, sometimes there were family photographs. I could also get inside this TV and appear, as it were, on television on the stage.

It was again semi-theatrical, semi-scripted, the anecdotes told by way of introduction were frivolous versions of more serious stories that appeared in the book. Sometimes the manuscript version was a lot more heart-breaking and I would tell a light-hearted version — a lot of the things were about, some of the things about family were quite dark. There were there were some things about my parents’ relationship, my dad’s more wayward nature which I unfortunately inherited for a period of my life. I suppose I was working all of that stuff out because it was all in the songs already, and all I did was point people to maybe what they had only suspected about the songs.

But the book, I gather, is real to the core. Yes? Everything in the book is you?

Yeah. I chose to put it out of chronological sequence, because I thought, “Well, Wikipedia does that.” I mean, you want the emotional sense of it. And I fictionalized a few episodes, not because I was being evasive, because I was trying to use fiction to summon up the mood. Rather than identify people, because it wasn’t their identity that was the point of the story, it was the feeling of the room I was in, and I only used that twice in the book.

Your songs are all, as far as I know, copyrighted Elvis Costello. Your book, however, is copyrighted by your given name, Declan MacManus.

Some of my songs are copyrighted — I changed it for a little while, and then I found that when people wanted to write with me or do my songs, of course, nobody had any idea who Declan MacManus was, so they wanted an Elvis Costello song. Again, that’s one of those things that I did kind of as a, just a little marker. It’s a gift to music critics to see something like that, because they want a real sense of psychological significance into it.

I was aware of the fact that the brand of my original appearance on the music scene was quite that: it was a brand in some people’s view, even though to me it wasn’t. It was my life. And the name was idiotic, and the appearance was idiotic. I played up to it, and I leaned into the character that was invented around me. But then, after a little while, it’s a bit boring and it gets in there and it gets dangerous as well you start to live it out, and make the wrong choices in so many different ways. You’ve got to get out of it.

Maybe part of it was reasserting there was a person who was completely on the outside of all of this ridiculous showbiz stuff that made the little tapes that got me my first record. I mean, I was making those in my bedroom. I still sing some of the other songs that I was writing then, and it was just the few that caught people’s ear were the ones that coincidentally landed me in the studio right when this supposed new thing was happening in rock and roll. I never really identified myself with it. Other people said, “You’re part of this new wave thing.” It was just a label somebody made up as a matter of convenience. It wasn’t a game plan.

You did seem to recognize even then that — I remember in your book, you wrote “The squarer I look,” which I gather is English for “angrier,” yes? “The angrier I look, the more the camera likes it.” How much of that early on was you putting on a creative persona?

photo 7 I saw an interview with ( jazz musician) Wayne Shorter (left) in a documentary about Lee Morgan where he talked about drinking brandy when he was younger, and he said it just created a little kind of place around himself in which he did his work. It wasn’t like he was really getting lit. It just took him out of the immediate environment. I understood exactly what that was. Even though I am a very different type of musician — obviously, I’m not on that same level, but I’m not an improviser in that way — but I know that I did the same thing with the, with aspects of the persona. The fact that I didn’t speak on record at times, it all just created a bit of room around me. Could get on with the job without being interrupted.

It was just that. And also, I was probably just anxious, nervous, as well, because I’m actually by nature quite shy. And then you have to learn bravado. And of course bravado you know easily. Then you get challenged particularly by boring self-satisfied people, whether it would be a radio DJ or a journalist that thought they’d worked you out. Of course, you’d go push it to a greater extreme just to confound them, just to horrify them more. And then also some people who were very kind.

There were some older journalists, a woman journalist from Wales who interviewed me very early on. I hadn’t got any guard up for her. I found her charming, and she seemed to kind of see that I was serious about what I did, in that way that sometimes younger people are a little earnest. And I see that. When I see the footage of it, it breaks my heart because I think there wasn’t any generational animosity or any of that nonsense. It was just genuine curiosity, somebody trying to do their job and me trying to do mine.

I’d like to ask you about your writing, and I could ask you all day about your writing; I don’t get to, but I think you’re a great writer, you’re a great songwriter but also I think lyrically alone, you’re a great writer, but a puzzling one sometimes. You’re a challenging one sometimes, on a couple dimensions. I’ll start with the one. Your lyrics are full of extraordinarily clever and memorable and cutting phrases and imagery that’s evocative and it’s specific; and yet often the actual theme or the plot of a story is a little bit removed and enigmatic, and I want to know is that a choice, is that you?

It is in some cases. I think there’s a really obvious shift in the writing on the album “Imperial Bedroom” (right) in ’81. I knew I was doing it then. That’s the first record I ever published the lyrics. Up until then I didn’t think that they should be written down. I felt they needed to be heard at the same time as as the music. They weren’t little poems, and I could have written poetry if it wanted to. I used to write poetry as a kid. I don’t know whether it was any good. But I knew how to write poetry. And I think poetry is the use of words where music is heard but none is playing, isn’t it? That’s one definition. I don’t know who said that; maybe I did. Where you hear music by the rhythm and the cadence of the words without there actually being a musical accompaniment. I mean, that’s one possible definition of poetry and I never really put myself on that level. It’s a very high art form.

So, I just wrote these things to be sung, and then I started to think, “Well, I like certain kinds of painting where there are more than one angle within the frame. Why can’t a song replicate that?” And cinematic cutting is like that. It fractures time. It goes backwards and just the active editing. You see it from one point of view and then you’re through a door and then you see the person standing there.

All those things, I’d kind of referred to them in songs from as early as “Watching the Detectives.” I mean, I’d use a stage or the film directions in the lyric. I’ve done that a few times, but I just push it further. And then, other songs came up that were very straightforward, and I just wasn’t very comfortable with the idea that if I wrote about events that we all shared, rather than, say, about matters of the heart, then I was less comfortable with making the easy slogan about it. I didn’t feel it was my job to do that or to tell people what to think, but to maybe try and find that little story that underlined something that I had seen that maybe somebody else hadn’t.

How often would you write a lyric that you would need to get rid of because it was too obvious, too on the surface?

I just didn’t write it. I mean, I don’t think I ever did get rid of it because I thought it was too obvious, I just didn’t write that. I wrote very fast. I realized right away if I was down a track that wasn’t going to work. I never wrote any songs about rock-and-roll that I can think of. What I mean is, there’s a lot of songs with the word rock-and-roll in the title. That kind of song that was celebrating the life? I wrote some songs that were kind of about the indulgences, but they were more from the outside. I never felt comfortable, even though I indulged just as much as anybody in those things, I always stood off from myself.

Yeah, there were some moments of hedonism, I suppose would be the word, but I always stood outside myself a little bit, going, “This is not really what you should be doing.” Maybe that’s just a way of making excuses for yourself, like a drunk who said, “Well, I could give up, but maybe just after this drink.” That kind of thing.

And you were drinking — by the way, which sounds horrible to me — Coke and Pernod?

Oh, that was just one afternoon. You don’t do that twice.

So along those lines of becoming the writer that you became, you wrote in your book, that you knew you hadn’t been born with the good looks and confidence necessary for popular success.

Face for the radio.

Face for the radio. But was that really true? Did you really believe that? Because in my reckoning of how you became who you are as an artist, you’re growing up with this father who’s in showbiz, and you have access to showbiz; and British music at the time was very exciting and there were rock stars being made all the time; and you were to my mind, at least, I hope you agree, phenomenally good and talented and hardworking, etc., etc.; and did you really draw the boundary where, for yourself, that I’m never going to be in the inner circle of stardom? Is that really the case?

Well, I think that a couple of things colour it. One is that I was exposed, I suppose, to some elements of early on. Just like anybody, you have an admiration for your parents’ ability to do whatever it is they do. Cook the dinner and go to work, and I’d go see my dad sometimes in the dance hall on a Saturday afternoon. That was one perspective of performance. And he brought music into the house that he was learning for the weekly broadcast.

Later on, after my parents separated, his life transformed. He then took on an appearance closer to, I’ve said in my show, closer to Peter Sellers in “What’s New Pussycat?” He grew his hair long and he started to wear fashionable clothes and listen to contemporary music, and started to incorporate their songs into what was otherwise a fairly unpromising environment of working-men’s clubs and social clubs, because he left the safety of the nightly gig with the dance band and decided he wanted to do his own thing.

So, that striking out and being independent thing was from his example, but all the way along, no matter what the music was or the style. And, bear in mind, my taste in music changed just like any teenager; from it was all about one thing, the next day it was all about another. It was always about the song. I’d seen the sheet music transformed into a radio performance. My father used to go and make a little bit of cash money doing cover records where they did note-for-note covers of things. So, the stardom of the individual people, with the exception of a band like The Beatles who everybody was fascinated and focused on all the way through those years and their various transformations; I didn’t really see that as something I could do.

I had spent the last two years of schooling in Liverpool, which at that time was musically very quiet in the early 70’s, and tried to make my own way playing my own songs. I had a partner, we sang in bars and any evening where they would let us on the stage, really; we were making tiny little bits of money just about covered our expenses, and I learned a little bit how to do it, but I never really thought— I looked at the television every Thursday to see Top of the Pops and saw the distance between the way I looked and felt and sounded and what was a pop singer right then, which was a lot of people in baker foil with eye makeup on; that was the music of that moment, the glitter, glam moment. That seemed very distant from a 17-year-old.

I never wanted to do that, though. I might be the only person in English pop music that that made a record that never wanted to be David Bowie, (left) while still loving everything he did. I never wanted to look like him. I just loved his records. It was enough for me that he made those records. I didn’t want to make them. I knew I couldn’t.

There’s also, so I don’t mean to summarize your music to you, but this is one person’s perception, and your music is extraordinarily diverse and interesting on a lot of levels over the years. But a lot of your writing shows a — I don’t know if “cynicism” is fair — distrust and frustration, and often the belief that too many people and especially institutions are cruel and corrupt, maybe not of their own design, but they are hypocritical; and I’m curious, if you accept my summary of that part-attitude in part in your writing; it’s not always that; if you accept that to some degree, whether you thought that maybe pop music, the kind of super popular pop music, couldn’t contain that commentary.

Oh no, I felt the opposite thing. I mean, I think, like any teenager, I was a little bit self-righteous when I when I was 17 and I thought I had discovered the secret because, I remember telling a teacher, a careers master, I wasn’t going to be in pop music, I was going to take words and I was going to set them to music. I’d discovered a magic formula, and he just said, “Oh, you want to be a pop singer.” And they were sneering and how ridiculous could that be. And it wasn’t like they were thwarting my ambition. I didn’t have any ambition. I was a purist; I was a Puritan.

What do you mean by that, a Puritan in what direction?

I wasn’t interested in those trappings. For one thing, I didn’t think I was a performer. I was almost certain that I was a songwriter!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!