BRINGING FLAMENCO CLUB TO STAGE:

BRINGING FLAMENCO CLUB TO STAGE:

Ensembles Vientos Flamencos

Teatro El Salineros, Arrecife, 20th January 2022.

by Norman Warwick

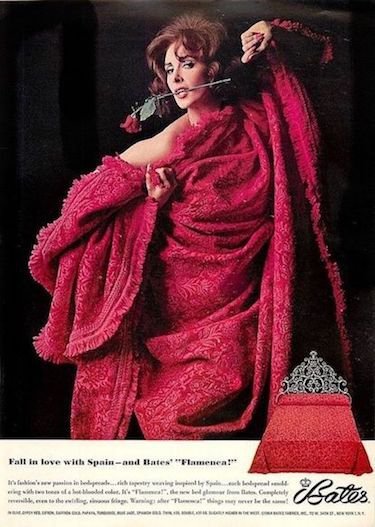

´During the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair, an advertisement for the Bates textile company in the Pavilion of Spain’s official guide book featured a fetchingly posed young woman, rose in mouth, with a ruby red bedspread draped over her body to form the likeness of a flamenco dress. The text beckons us to “fall in love with Spain—and Bates’ ‘Flamenca!’” and encourages us to discover “fashion’s new passion in bedspreads … each bedspread smoldering with two tones of a hot-blooded color.”

So opened a report by Sandie Holquin, published by The Smithsonian magazine in 2019.

´In the U.S. and elsewhere, flamenco is a pervasive marker of Spanish national identity. For proof of its currency in pop culture, look no further than Toy Story 3: Buzz Lightyear (right) is mistakenly reset in “Spanish mode,” and becomes a passionate Spanish flamenco dancer. Indeed, the world outside Spain often stereotypes the nation as inhabited by flamenco dancers, singers, and guitar players who are so “passionate,” they have little time to engage in the day-to-day world of the mundane.

Inside Spain, however, the relationship between the flamenco art form and Spanish national identity has been fraught for more than a century. Indeed, the world’s love of flamenco has long created problems within Spain, where the performance was once considered a vulgar and pornographic spectacle. Over the years, many Spaniards considered flamenco a scourge of their nation, deploring it as an entertainment that lulled the masses into stupefaction and hampered Spain’s progress toward modernity. Flamenco’s shifting fortunes show how Spain’s complex national identity continues to evolve to this day.

Flamenco, which UNESCO recently recognized as part of the World’s Intangible Cultural Heritage, is a complex art form incorporating poetry, singing (cante), guitar playing (toque), dance (baile), polyrhythmic hand-clapping (palmas), and finger snapping (pitos). It often features the call and response known as jaleo, a form of “hell raising,” involving hand clapping, foot stomping, and audiences’ encouraging shouts. Nobody really knows where the term “flamenco” originated, but all agree that the art form began in southern Spain—Andalusia and Murcia—but was also shaped by musicians and performers in the Caribbean, Latin America, and Europe.

Moreover, from the mid-nineteenth century on, flamenco entertainment spread quickly from southern Spain to the capital (Madrid) and onward to other Spanish urban centres, flourishing there as a consequence of the rise of a mass urban culture and increased foreign tourism.

The reason for flamenco’s horrible reputation among Spanish elites during the 19th and 20th centuries was that historically, performances were associated with the ostracized Gypsy (Roma) population in Spain, and they took place in seedy urban areas.

Spanish elites particularly despised how foreigners linked Spain with flamenco. Spain’s national identity had previously been defined by outsiders who tied the country to Inquisitors, beggars, bandits, bullfighters, Gypsies, and flamenco dancers. Usually foreigners imposed the flamenco identity onto Spain as a backhanded compliment to highlight Spain’s steadfast authenticity. The nation had not fallen prey to the soul-sucking effects of industrialization. But with very few exceptions, Spanish elites and social reformers never liked—nor wanted—this art form to represent themselves or their nation, and they fought flamenco fever with all the resources they could muster. But flamencomania proved much more difficult to eradicate than the so-called Black Legend: the negative propaganda, spread by Spain’s French and British rivals, that characterized Spain as the land of cruel Inquisitors, sadistic colonial rulers, repressive politicians, and intellectual and artistic yokels.

Flamenco came to encapsulate Spanish elites’ feelings of shame about the country’s declining status as a great power in the modern era. Flamenco’s critics were divided into three main groups: the Catholic Church and its conservative allies, left-leaning intellectuals and politicians, and leaders from revolutionary workers’ movements. During the convulsive period between the Restoration and the beginning of the civil war, from 1875 to 1936, these groups used flamenco to critique what they saw as Spain’s political, economic, and cultural ills.

The Catholic Church perceived flamenco as an offshoot of the sort of mass cultural entertainments that led to immodesty, the breakdown of the family, and the weakening of the Patria. But for many progressive intellectuals, by contrast, flamenco—along with its twin scourge, bullfighting—was thought to keep Spaniards in a stranglehold of backwardness. They saw the entertainment as a distraction that prevented Spaniards from solving the nation’s numerous ills, including a corrupt political system, a wildly inadequate and unequal educational system, a lack of infrastructure and technological know-how, and vast inequalities of wealth. Meanwhile, for working-class reformers and revolutionaries, flamenco and its concomitant lifestyle exploited people’s poverty and diverted workers away from becoming full actors in seeking revolution to end social, political, and economic inequality.

In reality, all of these groups used flamenco as a vessel to contain their dissatisfaction with the ideological and structural changes that emerged out of the French and Industrial Revolutions. They railed in newspaper diatribes against this form of entertainment, with some critics seeing flamenco as the perverted outcome of increased secularization, while others thought it showed resistance to progress and modernization. What they were really complaining about, however, was the permeation of modern mass culture into the daily lives of everyday citizens.

The many World’s Fairs of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries gave flamenco a boost, making Spanish Gypsy performers all the rage, especially in Paris. Flamenco “deep song” (cante jondo) received the blessings of European avant-garde artists such as Sergei Diaghilev and Claude Debussy (left) , who had attended flamenco performances at the Paris World’s Fairs of 1889 and 1900, and found it primal and authentic. That led Spanish intellectuals and artists such as Manuel de Falla and Federico García Lorca to elevate this form of flamenco to “high culture.” Thus, the support of Europeans outside Spain transformed the cultural meaning of flamenco for Spanish artists and intellectuals in much the same way that 20th-century European support for African-American jazz and blues aided their popularity in the United States.

But after the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War, from 1936 to 1939, flamenco performances in Spain diminished considerably. The Catholic Church and leaders of the Sección Femenina (the female wing of Spain’s Fascist Party) disavowed flamenco. To counteract its perceived evils, they promoted folk dancing and singing, encouraging a new kind of national identity predicated on Spanish regional diversity and cleansed of flamenco’s torrid reputation.

But by the 1950s, after years of international isolation, the Franco regime needed money. This led the regime to change course, promoting flamenco in order to jump-start Spain’s tourist industry. A tourism promoter named Carlos González Cuesta wrote, “We have to resign ourselves touristically to be a country of [Spanish stereotypes], because the day we lose the [Spanish stereotypes], we will have lost 90 percent of our attraction for tourists.”

So the Franco regime pandered to tourists’ love of flamenco, increasing the number of clubs that specialized in it, advertising female flamenco dancers on tourism and airline brochures, encouraging professional flamenco performers to star in Hollywood films, and featuring performers in traveling exhibitions like the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. These strategies worked; the regime was able to bring in millions of tourists and their money to help fund Spain’s economic boom of the 1960s.

After the death, in 1975, of Franco (right) the role of flamenco once again changed dramatically. The nearly simultaneous movements for regional autonomy within Spain and the growth of a world music culture complicated flamenco’s relationship to Spanish national identity. The foreign depiction of Spain as the land of flamenco, the not-quite European country with the Oriental-Gypsy soul, has been exploited by entrepreneurial spirits within Spain. That is not to say that flamenco flourishes today only to serve the interests of commerce. Artists, scholars, and historical preservationists have chosen to undertake serious study of the art form and to promote its historical and artistic significance for both Spain and Andalusia. In fact, one could say that flamenco today has undergone both extreme commercialization and renewed artistic and academic respect, once again demonstrating its complex relationship to Spanish national identity´.

Today we can, for example, look at The Romí Ciudad de La Laguna International Flamenco Festival (left) which arose in 2014 at the hands of its artistic director, José Heredia Santiago, and the courage of the women of the Romí Kamela Nakear Association, to pay homage to the gypsy woman and to several of the greatest amd most prestigious masters who have toured the world with their singing, dancing and playing.

The Festival continues to fan the flame of the best flamenco in the Canary Islands in what will be its eighth edition.

The main objective is to promote gypsy youth and promote and favour the professionalization of young flamenco musicians, which facilitates their socio-cultural incorporation to be able to participate in the “Promotion of young talents” program, which has been carried out since 2014.

What we saw last night on Lanzarote was a preview sample of a festival that opens on Saturday, April 24, at 7:00 p.m., Remedios Amaya, one of the artists most acclaimed by knowledgeable fans, first stepped on stage at a very young age sharing that very gypsy voice that even amazed himself. She has regained her strength again, after illness, and is now performing with renewed enthusiasm, showing that nothing can beat her.

The newest part of the festival is offered by the Turkish duo formed by Öykü Gürman and Berk Gürman. Twin brothers, they triumphed in their country in 2008 with a style that perfectly symbolizes the fusion of flamenco with traditional Turkish folklore. Öykü is also an actress, and her presentation in Spain is thanks to the Fugitive series, a true audience phenomenon. Berk is a guitarist and arranger who manages to take us with his music on a suggestive round trip from Al Andalus to the East, from Istanbul to Cádiz. His surprisingly original approach is full of magic.

In addition, the festival will feature a cast of prestigious artists such as the essential, Jorge Pardo, jazz and flamenco musician, tenor and soprano saxophonist and flutist, as well as internationally rated Samara Amaya (cantaora), Marina Valiente (dancer), El Perla(guitar, Ana María González(singer), Marina Reyes(singer), Isidro Suárez(percussion), Joaquina Amaya(singer), Juan Reyes “El Pollo”(guitar), who participate, to show a brushstroke of his art, ashe delivers and act full full of magic and talent.

The Lanzarote element of the Roma Ciadud de La Laguna Flamenco Festival 2022 was delivered on 20th January, in the midst of half a dozen wonderful concerts that were part of the 38th Festival Internacional de Music de Canarias. It felt at first as if the festival of flamenco might be overwhelmed by an international event in its 38th year. We should have known better. We should have known that nobody puts Baby Flamenco in a corner. She will wail and stamp her feet and strut her stuff, bringing us melodies and strutting her staff.

Flamenoc proved all that and more in the performance we saw at El Salinero Tatro in Arrecife, last night, under the banner of Ensembles Vientos Flamencos-

Perhaps due to being English and not steeped in folk lore and flamenco history we were eagerly chatting with our friends, Iain and Margaret who are accompanying us at all the events offered as part of the 38th annual Festival Internacial de Music de Canarias. We spent a leisurely couple of hours at La Garimba restaurant, looking out from its elevated vantage point down on to Charcos de Sin Gines at an incoming tide bobbing the hundreds of boats moored in the ´harbour´ that seemed somehow protected from the high winds racing round the island all week. This simple bar, serving mostly locals, we think, has a few tables dotted on an outside patio and two friendly young waiters brought us a salad and tapas of bread, canarian potatoes and mojo sauces, tortilla, which Iain and I agreed was the best on the island, garlic prawns, calamari, fried chicken, several bottles of beer sin alcohol, copious red wine and a creamy, chocolate dessert, as well as coffees Americano, Espresso and Cappucino.

We passed the time by wondering what the imminent concert would bring and by the time we arrived outside the theatre, after a very short drive through the city, we had pretty much decided it would be swirling dresses, stamping feet, finger clicking and pointing, haughty looking females and somewhat downtrodden and lustful and frustrated males. That, after all, is how flamenco has been presented in the past to tourists who see the art form as a slightly quirky cultural .spectacle

However, this constellation of flamenco stars, seen over Lanzarote led us to a different place. The Romí International Flamenco Festival instead brought together, a constellation of flamenco stars, introducing to an authentic cast of legends in Ensamble Vientos Flamencos, a top-level show in which some of the most revolutionary figures in the history of flamenco take part. There was hardly a raised hem in sight.

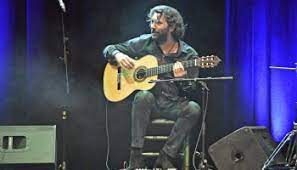

Instead, Jorge Pardo (sax and flute), Carles Benavent (electric bass) and Tino di Giraldo on drums, demonstrated the flamenco jazz style in which they have been pioneers. We also heard the guitars of Juan Carmona El Camborio and Josemi Carmona, key figures of the band Ketama

On percussion, we had the bandolero cajon master. Saray Muñoz, daughter of Tina (Las Grecas), currently the titular cantaora of the Spanish National Ballet, showing the enormous quality of her voice together with Montse Cortés, known as ‘La perla de La Mina’, the most requested and identifiable voice for flamenco dance and heard a key piece of her Antonio Canales shows. His latest work, ‘La rosa blanca’, has been produced by Javier Limón.

We also were able to hear the singer Antonio Carbonell, known for having represented Spain in the 1996 Eurovision Song Contest.

In what little dancing there was we had Gema and the cantaora Almaría and the voice of Juan Carrasco Soto “Juañares” were also present. and there was Gema Moneo from Jerez, a genuine representative of the purest gypsy dance.

The ensemble that is The Festival Internacional Flamenco Romí emerged in 2014 from the hand of its artistic director, José Heredia Santiago, and the courage of the women of the Romí Kamela Nakerar Association, to pay homage to gypsy women.

Flamenco is often an instrument of social comment, seeking to reduce inequalities and iniquities, and in that sense everyone below involved in this show deserves a namecheck.

Ensemble Cast – Flamenco Winds

Jorge Pardo – Saxophone & Flute

Josemi Carmona – Guitar

Juan Carmona «Camborio «- Guitar

Tino de Geraldo – Drums & Indian Tablas

Jose Manuel Ruiz Motos «Bandolero» – Percussionist

Carles Benavent – Bass

Saray Muñoz – Singer

Almaría – Singer

Juañares – Singer

Antonio Carbonell Singer

Gema Moneo – Dancer

Montse Cortés – Singer

That social element remains vitally important of course, for flamenco as music and dance not only safeguards the culture and traditions of this part of the world, even whilst spreading awareness and tolerance of gypsy status.

However the format also has to develop and flourish as do the islands, and it should not be forgotten that it is from tradition that modernity arrives. Flamenco is, at heart, also part of the entertainment industry that embraces music and dance.

It was obvious to we four friends from the moments the lights dimmed in the theatre that we were going to hear an authentic flamenco we had perhaps never hear before, There were occasional whoops and hollers from around the auditorium as flute flirted with percussion on a barely lit stage into a darkened arena. This somehow reminded me, perhaps as much because of the movements and mannerisms of the flautist, rather that the sound, of Ian Scott Anderson MBE (born 10 August 1947), a Scottish musician, singer and songwriter best known for his work as lead vocalist, flautist, acoustic guitarist and leader of British rock band Jethro Tull.

He is a multi-instrumentalist who, in addition to flute and acoustic guitar, plays keyboards, electric guitar, bass guitar, bouzouki, balalaika, saxophone, harmonica, and a variety of whistles. This Spanish flamenco music sounded not unlike the heavy rock drive music with which the Jethro Tull band described agricultural work on their album Heavy Horses.

There were staccato flamenco fixture fitted to a more sinewy beat and rhythm that sounded to Iain as if they carried Caribean calypso lines and throughout the next hour and a half the stage was busy with a cross traffic of around a dozen performers. Guitars, percussion, trumpet, flute, vocals, convoluted handclaps, apparently random cries of ole and bravo between the players and shouts of appreciation and encouragement from the audience create an atmosphere I associated with that which saw Ry Cooder draw wonderful music from purveyors of traditional music in Cuba, the title bearing their performing name of Buena Vista Social Club. The sound and film recordings the legendary guitarist captured of them made them internationally famous beyong their island.

Buena Vista Social Club is an ensemble of Cuban musicians established in 1996. The project was organized by World Circuit executive Nick Gold, produced by American guitarist Ry Cooder and directed by Juan de Marcos González.

The stage at El Salinero had taken on the smell of alcohol, a slight edginess adding to the thrill of performing and a patently evident love of this flamenco music.

The string playing was gorgeous and challenging, with each player pushing on the other and intermittent sax from a strolling player who wandered the stage like the ghost of Billie ´Buddy´ Boden, the hotshot cornetist and band-leader (right) , who died in 1931 and was , considered one of the fathers and founders of jazz.

There were girls in this ´backstreet club´created here, mostly encouraging the men by adding vocals and only occasionally strutting across the floor to ´cosy up´ to any musician creating something particularly impressive. This seemed to be one of those clubs in which to be a non-participatary audience was not allowed, so we call clapped, clicked our fingersm tapped our feet and yelled for more.

The levels of musicianship tonight (left) were of international class and very exciting and accessible. The flamenco vocals delivered here had not been sanitised for easy listening, however, and those of us from beyond flamenco fields find it difficult de to past and present social and gender issues.

It somehow felt as if we were staring through cigar-smoke to catch glimpses of these shadowy musicians in a darkened room. This was the real thing: flamenco stripped of any finery, a music at once of its own making but sharing so much in common from other music streams around the world.

As dropped off Iain and Margaret on the way home we made plans to meet up again for the following evening, as we all had tickets to see The Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra at the same theatre as part of the 38th Festival Internacional des Musica des Canarias.

as we said goodbye, Iain expressed again at how amazing it is that we four can all go together to watch such wonderful concerts and come away with four different, and hopefully plausible, interpretations of what we have heard and seen.

So, what of the music of The Lithuanean Chamber Orchestra.? We´ll let you know shortly.

Watch this space.

The primary source for this article was written by Sandie Holquin and published in 2019 by The Smithsonian magazine and we are also very grateful to various recent press releases.

In our occasional re-postings Sidetracks And Detours are confident that we are not only sharing with our readers excellent articles written by experts but are also pointing to informed and informative sites readers will re-visit time and again. Of course, we feel sure our readers will also return to our daily not-for-profit blog knowing that we seek to provide core original material whilst sometimes spotlighting the best pieces from elsewhere, as we engage with genres and practitioners along all the sidetracks & detours we take.

This article was collated by Norman Warwick, a weekly columnist with Lanzarote Information and owner and editor of this daily blog at Sidetracks And Detours.

Norman has also been a long serving broadcaster, co-presenting the weekly all across the arts programme on Crescent Community Radio for many years with Steve, and his own show on Sherwood Community Radio. He has been a regular guest on BBC Radio Manchester, BBC Radio Lancashire, BBC Radio Merseyside and BBC Radio 4.

As a published author and poet he was a founder member of Lendanear Music, with Colin Lever and Just Poets with Pam McKee, Touchstones Creative Writing Group (where he was creative writing facilitator for a number of years) with Val Chadwick and all across the arts with Robin Parker.

From Monday to Friday, you will find a daily post here at Sidetracks And Detours and, should you be looking for good reading, over the weekend you can visit our massive but easy to navigate archives of over 500 articles.

The purpose of this daily not-for-profit blog is to deliver news, previews, interviews and reviews from all across the arts to die-hard fans and non- traditional audiences around the world. We are therefore always delighted to receive your own articles here at Sidetracks And Detours. So if you have a favourite artist, event, or venue that you would like to tell us more about just drop a Word document attachment to me at normanwarwick55@gmail.com with a couple of appropriate photographs in a zip folder if you wish. Beiung a not-for-profit organisation we unfortunately cannot pay you but we will always fully attribute any pieces we publish. You therefore might also. like to include a brief autobiography and photograph of yourself in your submission. We look forward to hearing from you.

Sidetracks And Detours is seeking to join the synergy of organisations that support the arts of whatever genre. We are therefore grateful to all those share information to reach as wide and diverse an audience as possible.

correspondents Michael Higgins

Steve Bewick

Gary Heywood Everett

Steve Cooke

Susana Fondon

Graham Marshall

Peter Pearson

Hot Biscuits Jazz Radio www.fc-radio.co.uk

AllMusic https://www.allmusic.com

feedspot https://www.feedspot.com/?_src=folder

Jazz In Reading https://www.jazzinreading.com

Jazziz https://www.jazziz.com

Ribble Valley Jazz & Blues https://rvjazzandblues.co.uk

Rob Adams Music That´s Going Places

Lanzarote Information https://lanzaroteinformation.co.uk

all across the arts www.allacrossthearts.co.uk

Rochdale Music Society rochdalemusicsociety.org

Lendanear www.lendanearmusic

Agenda Cultura Lanzarote

Larry Yaskiel – writer

The Lanzarote Art Gallery https://lanzaroteartgallery.com

Goodreads https://www.goodreads.

groundup music HOME | GroundUP Music

Maverick https://maverick-country.com

Joni Mitchell newsletter

passenger newsletter

paste mail ins

sheku kanneh mason newsletter

songfacts en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SongFacts

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!