TO SIR WITH LOVE, commendation and commemoration

TO SIR WITH LOVE, commendation and commemoration

by Norman Warwick

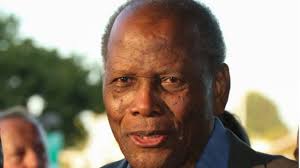

He was an electrifying presence on-screen. In life, he used his charisma and his renown as forces for change.

Sidney Poitier, best known for history-making roles in such films as Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat Of The Night, and Lilies Of The Field made immense contributions to the civil rights movement. Dr. Russell Wigginton, president of the Memphis-based National Civil Rights Museum, points to Poitier’s staunch support of Martin Luther King Jr. and the actor’s participation in the 1966 March Against Fear, through one of Mississippi’s most deeply segregated regions.

Poitier, who died Jan. 6 at the age of 94, worked his way up an overwhelmingly white industry by playing against type. He famously refused to take on stereotypical roles for a Black male actor. With his talent and his tenacity, Poitier built bridges and opened doors for so many. At the same time, he was dedicated to civil rights.

He was there on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., during the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. He witnessed King delivering his historic I Have A Dream”speech.

Such was Poitier’s contribution and legacy that the National Civil Rights Museum honoured him with its Freedom Award in 2001.

“Despite his celebrity, he did what he believed in because he felt it was the right thing to do. He did not seek or need outward reinforcement or attention or accolades for doing the right thing´, Wigginton says. Poitier dedicated much of his resources and presence to Mississippi in the 1960s because the state was a hotbed of segregation and exploitation of Black residents.

“He understood the significance of him being in Mississippi and being with Dr. King. For somebody who had so much limelight, he didn’t seem to share that as much as doing the principled, important work of setting an example and showcasing to the world that this is what he stood for´, Wigginton says.

King and Poitier had many common bonds, including the burden of celebrity. ´Everything they did was being monitored observed and meaning made from´, Wigginton says. “Being together allowed them to kind of relax in a way that they probably couldn’t around a lot of people and to have untethered conversation and share their deepest thoughts about the world and their purpose´.

Poitier’s activism filtered into his art. In Norman Jewison’s taut 1967 drama In the Heat Of The Night, Poitier’s Virgil Tibbs delivered a slap to Larry Gates’ racist plantation owner Mr. Endicott that had a huge impact on the country. As Poitier recalled in his 2000 memoir The Measure Of A Man, the initial version of the scene was quite different. ´In the original script, I looked at him with great disdain and, wrapped in my strong ideals, walked out´, he wrote. ´That could have happened with another actor playing the part, but it couldn’t happen with me´.

Back in 1967, King noted Poitier’s contributions, calling him ´a man of great depth, a man of great social concern, a man who is dedicated to human rights and freedom´.

I was just entering the second half of my teenage years, and was part of a generation that had already seen the assassination of some of the heroes our parents said had been going to change the world for the better. It was hard at that age to understand the segregation and apartheid I would hear mentioned as I passed by the telly on my way out to play football in inter-racial teams on the streets of a council estate in Manchester. Dave Price was a big. stocky coloured lad who played in goal, brilliantly, on concrete pitches, and Richard Swift was a son of West Indian parents. Stereotyping would have cast him as a fast bowler, but instead he was snake-hipped ´winger´ who could dribble round three lamp-posts and couple of abandoned bi-cycles before swerving the plastic ball from twenty yards, just inside the far post that was really just a jacket on the ground. We fell out occasionally because of the colours of the imaginary shirts we were wearing to represent United, City, Bolton, Bury or Rochdale (listed in decreasing order of popularity). We never fell out about the colour of our skins, though. All the long marches and the vows to not be moved and to overcome were for our parents´ generation; we working class teenagers of the sixties instead kicked lumps out of each other in scratch-matches that somehow built grudging admirations and loyal friendships.

I was aware only from news footage that Martin Luther King, Joan Baez and Sidney Poitier were constantly working as agents for change.

Now at the age of seventy, in times when my sporting heroes are taking the knee to remind us, more than half a century after the tumult of the sixties, that Black Lives Matter I hang my head in despair. I wish I´d done more. I wish I had spoken out. And I recognise how much worse it could be today had people like Baez and Poitier not put their careers and, indeed, their lives on the line.

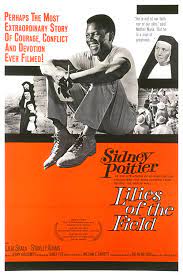

I now realise that ´Where baseball had Jackie Robinson, the movies had Sidney Poitier. The actor broke colour barriers with his excellent body of early work. He became the first Black man to win the best Actor Award at America’s most prestigious and visible film awards, (for his work on 1963’s Lilies of the Field, left) ). This made him one of the most high-profile and successful Black movie stars of the Golden Age.

Sadly, after a trailblazing career on and off-screen, Poitier has recently died at age 94.

The office of the Bahamian Minister of Foreign Affairs confirmed the death of an actor who also once served as the Bahamian ambassador to Japan. This political position was one of many real life roles of Poitier’s diverse acting career: Aside from an Honorary Oscar, his win for Lilies Of The Field and a nomination for The Defiant Ones, Poitier (right) earned multiple Emmy nods, a knighthood, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom as he continued acting and directing until the 1990s.

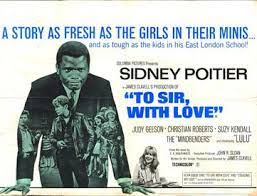

He also, alongside long-time friend Harry Belafonte, (left) was an ideological and financial supporter of the Civil Rights Movement. While his films broke down racism through sheer portrayals of strong, complex, often self-assured Black men—1967’s To Sir With Love, In The Heat Of The Night and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner serving as one of the strongest single years of any actors’ careers—his work behind the scenes reflected this dedication to progressiveness.

´I go in front of a camera with a responsibility to be at least respectful of certain values´, Poitier told the Museum of Living History. ´My values are not disconnected from the values of the Black community´.

And beyond that, he was fantastic. Warm, confident and with a dazzling control over his face, voice and body, Poitier’s movie stardom was well-deserved and put to good use. Last year, Arizona State University named their film school in honour of Poitier and his incredible legacy. At the time, Steven J. Tepper, Dean of the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts at ASU, said, ´Sidney Poitier is a national hero and international icon whose talents and character have defined ethical and inclusive filmmaking´.

Very few given the title “icon” deserve it, but here, it’s true.

Lillies of the Field was a 1963 American comedy drama film adapted by James Poe from the 1962 novel of the same name by William Edmund Barrett, and stars Sidney Poitier, Lilia Skala, Stanley Adams, and Dan Frazer. It was produced and directed by Ralph Nelson. The film explored issues of faith and is especially noted for Sidney Poitier’s historic Academy Award win as he became the first African American to win an Oscar for best actor.

Poitier portrayed Homer Smith, a wandering ex-GI who encounters an order of German nuns in Arizona. The nuns persuade him to perform odd jobs on their farm, and the tough-as-nails mother superior (played by Lilia Skala) eventually enlists his help in building a chapel. Despite several setbacks, he completes the chapel and in the process earns the respect and admiration of the nuns and the local townspeople.

Ironically, given the social significance of Lilies of the Field, Smith’s race is never brought up in the film. Poitier’s Academy Award win marked the first time a competitive Oscar had ever been awarded to an African American male. (James Baskett had received an honorary Academy Award in 1948 for his role as Uncle Remus in Song of the South [1946].) The role of the construction company owner who gives Smith a job was played by director/producer Ralph Nelson, who refused to take screen credit for his performance.

To Sir With Love saw Poitier play a novice teacher facing a class of rowdy, undisciplined working-class punks in this classic film that reflected some of the problems and fears of teens in the 60s. Sidney Poitier gives one of his finest performances as Mark Thackeray, an out-of-work engineer who turns to teaching in London’s tough East End. The graduating class, led by Denham, Pamela and Barbara, sets out to destroy Thackeray as they did his predecessor by breaking his spirit. But Thackeray, no stranger to hostility, meets the challenge by treating the students as young adults who will soon enter a work force where they must stand or fall on their own.

A.D. Murphy has written extensively about this film in Variety and praised it highly even whilst putting it unflinchingly under the miscroscope.

He says that ´In The Heat Of The Night, thanks to an excellent Sidney Poitier performance, and an outstanding one by Rod Steiger, (the two actors shown left) overcomes some noteworthy flaws. The film is, he says, an absorbing contemporary murder drama, set in the deep, red-necked South. Most production elements are well co-ordinated by producer Walter Mirisch, and enhanced by an excellent cast. Norman Jewison directed, sometimes in pretentious fashion, an uneven script. Nevertheless, hot box office figures. were achieved by the United Artists release.

Novelist John Ball has written three books about a Negro gumshoe named Virgil Tibbs, Heat being the first. Stirling Silliphant has adapted it into an erratic screenplay which indulges in heavy-handed, sometimes needless plot diversion, uncertain character development, and a rapid fire denouement. As a matter of fact, suddenness of climax suggests that the creative team went dry. The film clearly is a triumph over some of its basic parts.

The intriguing plot has Poitier as the detective, accidentally on a visit to his Mississippi hometown where a prominent industrialist is found murdered. Arrested initially — and ironically — on the assumption that a Negro, out late at night must have done the deed, Poitier later is thrust, by his boss in Philadelphia, his own conscience, and a temporary anti-white emotional outburst, into uneasy collaboration with local sheriff Steiger.

Steiger’s transformation from a diehard Dixie bigot to a man who learns to respect Poitier stands out in smooth comparison to the wandering solution of the murder. En route, assorted characters include policeman Warren Oates, sexpot Quentin Dean and her brother, James Peterson, Lee Grant, as the murdered man’s widow, unreconstructed manor lord Larry Gates, glib mayor William Schallert, town abolitionist Beah Richards, sleazy greasy-spoon clerk Anthony James, and petty criminal Scott Wilson.

Script emphasis in opening scenes telegraph something, and indeed that occurs. But the explanation of the murder takes only several seconds and many audiences will have to discuss the matter before reaching agreement; even a fast synopsis reading leaves some questions. Jewison’s direction of his cast, however, is excellent, particularly the relationship between the two above-title stars, although some dialect is obscure.

Exactly why Gates’ scene is there is unclear — perhaps the face-slapping bit with Poitier was considered daring, although incorporation could have been smoother. Exactly why Poitier seeks out Miss Richards — for that matter, the details of his entrée there — are unclear. These flaws, and others to follow, are noteworthy in view of their substantial, obvious presence.

Miss Dean, Patterson, Wilson and James are “introduced” herein, and each has a distinct potential. Oates and Miss Grant are just right, and the rest of cast supports in solid fashion.

Jewison’s presumed influence on final editing is not up to his dramatic direction. In an early scene, for example, Wilson is pursued by hounds to a large bridge, over which lies another state — and freedom. What could have been a compelling and ironic frustration becomes a tedious intercutting of a long zoom, then Steiger sitting in a patrol car, waiting for his prey, Steiger driving at speeds which process work indicates must be about 80 m.p.h., then Wilson shuffling along with the car behind, and finally a long-shot which ends it all. The Scene does not play; it fizzles out completely.

Then, too, the subjective camera, used several times, gets a little old. Wilson’s flight through undergrowth is overemphasized by dizzying shots; frames, not feet, of film can convey the desired impression. Also a peeping-tom view of some hoods getting into a car for the climactic confrontation is needlessly obscured by foliage — and the obscured characters only confuse who’s who.

On the peeping tom bit, Oates’ voyeuristic observations of Miss Dean, a nubile, full-breasted nifty to be sure, is followed by a long-held shot for audience voyeurs; again, too much of a good thing – cinematically, that is. Perhaps there is no door-screen, or convenient strut in the foreign version.

Haskell Wexler’s DeLuxe lensing captures the desired drabness of the locale for mood-enhancement, but in several scenes it intrudes. Must auto departures so regularly start from a tail light? Only a nearby tire thief would see it that way. Difference, for its own sake, is pretension.

An excellent score has been provided by Quincy Jones whose title tune is sung by Ray Charles to good effect. Hal Ashby, also billed as assistant to the producer, executed editing to 109 minutes, in an over-all high quality, with exceptions as noted. Sound recording is excellent, as are other production credits. Out-of-focus title effects are credited to Murray Naidich, who did a first rate job; UA might include an alerting note to booth-men however, to ensure a smooth opening.

Jewison had, after switching from TV, directed five programmers before The Mirisch Corporation sponsored his The Russians Are Coming, The Russings Are Coming, which landed him firmly on the film map, and extended his ties with Mirisch for five more x- films , including In The Heat Of The Night.

That temperature also informed, I feel, the later production of Mississippi Burning, starring Gene Hackman.

Mississippi Burning is a 1988 American historical crime thriller film directed by Alan Parker that is loosely based on the 1964 murder investigation of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in Mississippi. It stars Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe as two FBI agents investigating the disappearance of three civil rights workers in fictional Jessup County, Mississippi, who are met with hostility by the town’s residents, local police, and the Ku Klux Klan.

Screenwriter Chris Gerolmo began the script in 1985 after researching the 1964 murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner. He and producer Frederick Zollo presented it to Orion Pictures, and the studio subsequently hired Parker to direct the film. The writer and director had disputes over the script, and Orion allowed Parker to make uncredited rewrites. The film was shot in a number of locations in Mississippi and Alabama, with principal photography from March to May, 1988.

On release, Mississippi Burning was criticized by activists involved in the civil rights movement and the families of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner for its fictionalization of events. Critical reaction was mixed, though the performances of Hackman, Dafoe and Frances McDormand were generally praised. The film grossed $34.6 million in North America against a production budget of $15 million. It received seven Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, and won for Best Cinematography.

On June 21, 1964, civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were arrested in Philadelphia, Mississippi by Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price, and taken to a Neshoba County jail. The three men had been working on the “Freedom Summer” campaign, attempting to organize a voter registry for African Americans Price charged Chaney with speeding and held the other two men for questioning. He released the three men on bail seven hours later and followed them out of town. After Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner failed to return to Meridian, Mississippi on time, workers for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) placed calls to the Neshoba County jail, asking if the police had any information on their whereabouts. Two days later, FBI agent John Proctor and ten other agents began their investigation in Neshoba County. They received a tip about a burning CORE station wagon seen in the woods off of Highway 21, about 20 miles northeast of Philadelphia. The investigation was given the code name “MIBURN” (short for “Mississippi Burning”),] and top FBI inspectors were sent to help with the case.[2]

On August 4, 1964, the bodies of the three men were found after an informant nicknamed “Mr. X” in FBI reports passed along a tip to federal authorities. They were discovered underneath an earthen dam on a 253-acre farm located a few miles outside Philadelphia, Mississippi.[10] All three men had been shot. Nineteen suspects were indicted by the U.S. Justice Department for violating the workers’ civil rights. On October 27, 1967, a federal trial conducted in Meridian resulted in only seven of the defendants, including Price, being convicted with sentences ranging from three to ten years. Nine were acquitted, and the jury deadlocked on three others

In 2002, Jerry Mitchell, an investigative reporter for The Clarion-Ledger, discovered new evidence regarding the murders. He also located new witnesses and pressured the state of Mississippi to reopen the case Stevenson High School teacher Barry Bradford and three of his students aided Mitchell in his investigation after the three students chose to research the “Mississippi Burning” case for a history project.

The identity of Mr. X. was a closely held secret for 40 years. In the process of reopening the case, Mitchell, Bradford and the three students discovered the informant’s identity. Mr. X was revealed to be Maynard King, a highway patrolman who revealed the location of the civil rights workers’ bodies to FBI Agent Joseph Sullivan. In 2005, one perpetrator, Edgar Ray Killen, was charged for his part in the crimes. He was convicted of three counts of manslaughter, and received a 60-year sentence. Killen died in prison on January 11, 2018.

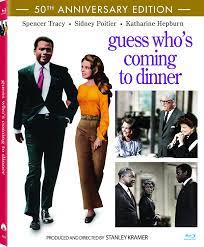

The timing of the release of Guess Who´s Coming To Dinner in1967 was slightly too close to home for me and my sixteen year old pals. Many of us had just started college after years at our single-gender schools for boys and girls. Just as were learning that mingling and meeting might not be the stuff of our school fantasies came Guess Who´s Coming To Dinner to remind us that in those quaintly old-fashioned and puritanical times the rites of passage of romance meant meetings with the parents even of romantic partners who might not last till Monday, let alone lead to marriage. I remember fancying Frances who sometimes served in her parents´ ice cream shop. I asked her out but she told I would have to ask her dad´s permission. He granted that permission on a Tuesday afternoon and in the evening I took Fran to watch Manchester United Reserves play Sunderland Reserves because I could get us in free with my dad´s season tickets. The quizzing from her dad proved pointless,…..it was a freezing cold night, she didn´t like Bovril out of plastic cup, and there were no goals in a boring match. In football terms that romance was all over by half time !

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism, an example of which I found at the website bearing his name.

´Yes´, he confirmed, ´there are serious faults in Stanley Kramer’s “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” but they are overcome by the virtues of this delightfully old-fashioned film. It would be easy to tear the plot to shreds and catch Kramer in the act of copping out. But why? On its own terms, this film is a joy to see, an evening of superb entertainment.

Entertainment, I think, is the key word here. Kramer has taken a controversial subject (interracial marriage) and insulated it with every trick in the Hollywood bag. There are glamorous star performances by Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy made more poignant by his death. There is shameless schmaltz (the title song, so help me, advises folks to give a little, take a little, let your poor heart break a little, etc.). The minor roles are filled with crashing stereotypes, like a Negro maid who must be Rochester’s sister and an Irish monsignor with a brogue so fey and eyes so twinkling he makes Bing Crosby look like a Protestant.

And there is the plot, borrowed from countless other drawing room comedies about “ineligible” suitors. Only this time the controversial suitor is not a socialist (“Man and Superman”), a newspaper reporter (“The Philadelphia Story”) or even a spinster (“Cactus Flower“) — but a Negro.

Of course, the negro is Sidney Poitier. He is a noble, rich, intelligent, handsome, ethical medical expert who serves on United Nations committees when he’s not hurrying off to Africa, Asia, Switzerland and all those other places where his genius is required. During a vacation in Hawaii, he meets Katharine Houghton, and they fall in love and come home to break the news to her parents.

And there is the plot, borrowed from countless other drawing room comedies about “ineligible” suitors. Only this time the controversial suitor is not a socialist (“Man and Superman”), a newspaper reporter (“The Philadelphia Story”) or even a spinster (“Cactus Flower“) — but a Negro.

Miss Hepburn takes the news rather well (“Just let me sit down a moment and I’ll be all right”), but Tracy has his doubts. Although he is a liberal newspaper publisher and a crusader against prejudice, he doesn’t want to be hurried into making up his mind. And that’s the trouble. Poitier has to catch the 10 p.m. flight to Geneva, you see, so Tracy has to decide before then.

It is easy to ridicule this deadline as contrived and artificial: and it is easy to argue that Poitier’s character is too perfect to be convincing. But neither of these aspects bothered me. The artificial deadline is a convention of drawing room comedies. It provides automatic suspense and keeps the action within a short span of time. And Poitier’s “perfect Negro” is no more perfect than Miss Houghton’s perfect liberal daughter, Miss Hepburn’s perfect Rock of Gibraltar mother and Tracy’s perfect Spencer Tracy.

The things that did bother me were more subtle. Despite Poitier’s reluctance, Miss Hougton insists that HIS parents also be invited to dinner. They are a pleasant middle-aged couple (played by Roy E. Glenn Sr. and Beah Richards), who turn out to be the most believable characters in the story. But their presence leads to two troublesome scenes.

The first occurs when Poitier (who has been unfailingly polite and deferential to Tracy) backs his own father into a corner and lectures him. The Negro father, like the white one, opposes interracial marriage. And Poitier, who has already agreed to abide by Tracy’s decision, cruelly attacks his own father’s position.

What it boils down to, then, is that the two fathers are overcome by implied attacks on their masculinity. The race question becomes secondary; what Tracy really had to decide is if he feels inadequate as a man. Kramer accomplishes this transition so subtly you hardly notice it. But it is the serious flaw in his plot, I think.

Still, perhaps Kramer was being more clever than we imagine. He has pointed out in interviews that his film does accomplish its purpose, after all. And it does. Here is a film about interracial marriage that has the audience throwing rice. The women in the audience can usually be counted on to identify with the love story. I suppose. But what about those men? Will love conquer prejudice? I wonder if Kramer isn’t sneaking up on one of the underlying causes of racial prejudice when he implies that the fathers feel their masculinity threatened.

All of these deep profundities aside, however, let me say that “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” is a magnificent piece of entertainment. It will make you laugh and may even make you cry. When old, gray-haired, weather-beaten Spencer Tracy turns to Katharine Hepburn and declares, by God, that he DOES remember what it is like to be in love, there is nothing to do but believe him.

The above films are a legacy of excellent on-screen work and it is for some of the aforementioned films as well as To Sir With Love, he will be best remembered. The latter deserves recongition not only for Poitier´s acting but also for the title song that b rought a new maturity to UK pop stgar Lulu.

Away from the screen, too Poitier was an agent of change for the better.

He was there on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., during the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. He witnessed King delivering his historic “I Have a Dream” speech.

Such was Poitier’s contribution and legacy that the National Civil Rights Museum honored him with its Freedom Award in 2001.

“Despite his celebrity, he did what he believed in because he felt it was the right thing to do. He did not seek or need outward reinforcement or attention or accolades for doing the right thing,” Wigginton says. Poitier dedicated much of his resources and presence to Mississippi in the 1960s because the state was a hotbed of segregation and exploitation of Black residents.

“He understood the significance of him being in Mississippi and being with Dr. King. For somebody who had so much limelight, he didn’t seem to share that as much as doing the principled, important work of setting an example and showcasing to the world that this is what he stood for,” Wigginton says.

King and Poitier had many common bonds, including the burden of celebrity. “Everything they did was being monitored observed and and searched for ´meaning´, Wigginton says. “Being together allowed them to kind of relax in a way that they probably couldn’t around a lot of people and to have untethered conversation and share their deepest thoughts about the world and their purpose.”

Back in 1967, King noted Poitier’s at depth, a man of great contributions, calling him “a man of great social concern, a man who is dedicated to human rights and freedom.”

Poitier’s activism filtered into his art. In Norman Jewison’s taut 1967 drama “In the Heat of the Night,” Poitier’s Virgil Tibbs delivered a slap to Larry Gates’ racist plantation owner Mr. Endicott that had a huge impact on the country.

Poitier´s 2000 memoir The Measure Of A Man, clearly shows that the actor realised his the strength of the platform his film work was building for him and from there he helped to awaken the world to the inequities of racial and colour prejudices.

Nothing summarises Sidney Poitier, the man, better than his citation on The Martin Luther King Junior National Historic Site

Born February 20, 1927, Sidney Poitier’s pioneering career has had a tremendous impact on American culture. In the early ’50s, he was the top and virtually sole African-American film star—the first black actor to become a hero to both black and white audiences. Poitier was also the first black actor to win a prestigious international film award. With his unique career, Sidney Poitier helped change many stubborn racial attitudes that had persisted in this country for centuries. He has built the bridges and opened the doors for countless artists in succeeding generations. He is an actor who stood for hope, for excellence, and who has given happiness to millions of people around the world. Paying tribute to Sidney Poitier in 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “He is a man of great depth, a man of great social concern, a man who is dedicated to human rights and freedom.”

Most recently, he had turned to writing, authoring autobiographies and a novel. He’s remained off-screen since doing some documentary work and a Larry King appearance in 2008, but his massive four-decade body of work stands tall—just as influential and important as it was when each film was released.

Poitier is survived by his wife and daughters.

Steve Bewick´s broadcast of Hot Biscuits Jazz Show this week features Gary Heywood-Everett exploring Matt Parker`s contention that British progressive Jazz was all pervasive in the British pop and art scene of the 60’s. This includes audio from Joe Harriot, Tubby Haynes and Eric Dolphy and much more. If this sounds interesting share the word and tune in 24/7 for my new weekly shows and archives at www.mixcloud.com/stevebewick/

The primary sources for this article were written by A D Murphy and originally published in Variety and an on line articel by Pulitzer Prize winning writer, Robert Ebert.

In our occasional re-postings Sidetracks And Detours are confident that we are not only sharing with our readers excellent articles written by experts but are also pointing to informed and informative sites readers will re-visit time and again. Of course, we feel sure our readers will also return to our daily not-for-profit blog knowing that we seek to provide core original material whilst sometimes spotlighting the best pieces from elsewhere, as we engage with genres and practitioners along all the sidetracks & detours we take.

This article was collated by Norman Warwick, a weekly columnist with Lanzarote Information and owner and editor of this daily blog at Sidetracks And Detours.

Norman has also been a long serving broadcaster, co-presenting the weekly all across the arts programme on Crescent Community Radio for many years with Steve, and his own show on Sherwood Community Radio. He has been a regular guest on BBC Radio Manchester, BBC Radio Lancashire, BBC Radio Merseyside and BBC Radio Four

As a published author and poet he was a founder member of Lendanear Music, with Colin Lever and Just Poets with Pam McKee, Touchstones Creative Writing Group (where he was creative writing facilitator for a number of years) with Val Chadwick and all across the arts with Robin Parker.

From Monday to Friday, you will find a daily post here at Sidetracks And Detours and, should you be looking for good reading, over the weekend you can visit our massive but easy to navigate archives of over 500 articles.

The purpose of this daily not-for-profit blog is to deliver news, previews, interviews and reviews from all across the arts to die-hard fans and non- traditional audiences around the world. We are therefore always delighted to receive your own articles here at Sidetracks And Detours. So if you have a favourite artist, event, or venue that you would like to tell us more about just drop a Word document attachment to me at normanwarwick55@gmail.com with a couple of appropriate photographs in a zip folder if you wish. Beiung a not-for-profit organisation we unfortunately cannot pay you but we will always fully attribute any pieces we publish. You therefore might also. like to include a brief autobiography and photograph of yourself in your submission. We look forward to hearing from you.

Sidetracks And Detours is seeking to join the synergy of organisations that support the arts of whatever genre. We are therefore grateful to all those share information to reach as wide and diverse an audience as possible.

correspondents Michael Higgins

Steve Bewick

Gary Heywood Everett

Steve Cooke

Susana Fondon

Graham Marshall

Peter Pearson

Hot Biscuits Jazz Radio www.fc-radio.co.uk

AllMusic https://www.allmusic.com

feedspot https://www.feedspot.com/?_src=folder

Jazz In Reading https://www.jazzinreading.com

Jazziz https://www.jazziz.com

Ribble Valley Jazz & Blues https://rvjazzandblues.co.uk

Rob Adams Music That´s Going Places

Lanzarote Information https://lanzaroteinformation.co.uk

all across the arts www.allacrossthearts.co.uk

Rochdale Music Society rochdalemusicsociety.org

Lendanear www.lendanearmusic

Agenda Cultura Lanzarote

Larry Yaskiel – writer

The Lanzarote Art Gallery https://lanzaroteartgallery.com

Goodreads https://www.goodreads.

groundup music HOME | GroundUP Music

Maverick https://maverick-country.com

Joni Mitchell newsletter

passenger newsletter

paste mail ins

sheku kanneh mason newsletter

songfacts en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SongFacts

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!