LISTENING TO A BEAT POET

LISTENING TO A BEAT POET

With Norman Warwick

Ever since primary school, and throughout my adult life, my preferred methods of learning have been from pretty much any source rather than reading textbooks. I have always felt I learn more from a writer I trust than ever I do from an encyclopaedia. I learn more about history from songs and films (even allowing for the fictionalisation) and more about geography, too.

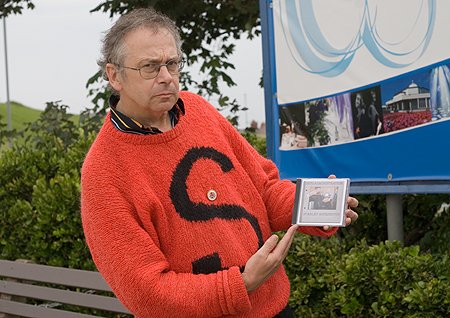

My question as a kid was, and is today, why would I ever look at a railway timetable when I could hear The Monkees telling me that The Last Train To Clarksville is at the platform, or Steve Goodman informing me that The Train They Call The City Of New Orleans will have gone five hundred miles by day is done. If I am ever unsure about where on the landscape I am my old friend Gene Pitney will remind me that I am only 24 Hours From Tulsa and should I need reminding of the changes to transportation over the last three quarters of a century I only have to listen to Wes McGhee lamenting that ´they say last call, where they used to say train time´ and I know that airports have replaced railways stations. Stanley Accrington shouts across to tell me The Last Train To Bacup Has Gone even as Tom Russell asks where he can board The Next Train Smoking.

Do I want to read a text book telling me about iambic pentameter or line-end inversions? No, I prefer to hear for myself that sound when time, like a leaf, down drops. I care not that Do Not Go Gentle is a villanelle but I do want to learn how Dylan Thomas used that technique to create his own kind of blues.

Perhaps I have always asked the wrong questions. Of course I should be asking how to write beat poems, but I prefer to ask who writes them and why and what are they hoping to achieve and where and when they first started doing it. To be fair, search engines like Google (or others that are also available) are pretty damned good at anticipating those questions and often present quite specific answers, but to find out more about The Beat Poets I began with a writer who never fails to teach me something.

The piece I began reading, therefore, was written by Geoffrey Himes and appeared in the Paste on-line magazine. So, of course, his feature didn´t open with a recollection of some early poetry slam in an American bar, but instead his words set out from a Clash concert in Manhattan, on a pier into a river on which stood a paddle-steamer and a warship.

It was August 31st in 1982, a date remembered by Himes, as the only time he ever saw The Clash (left) perform live.

´I was on an asphalt wharf jutted out into the Hudson River; nearby were a paddlewheel showboat and a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier bristling with radar and fighter jets´, he recalled, to open his article. ´It was a fitting backdrop for a band committed to resisting everything a warship and a nostalgia vessel stood for.´

Text books don´t often serve the memorable lines that commit a name to memory, leastways not in the way Himes does.

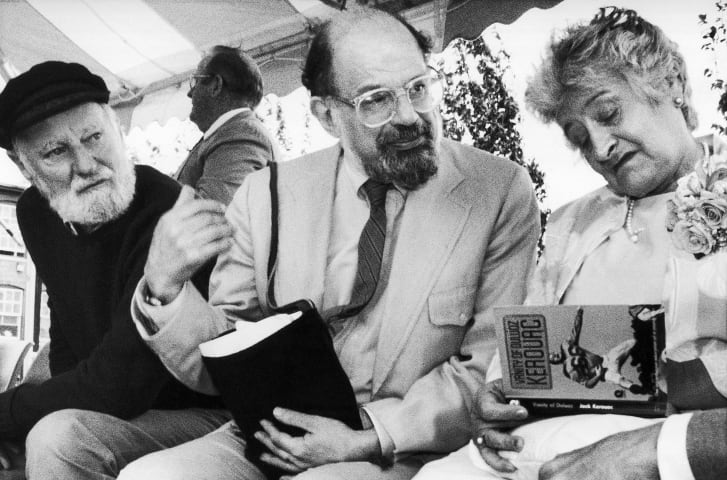

´Wandering through the crowd before the show,´ he showed us rather than told us. ´was the legendary beat poet Allen Ginsberg with his balding head, rabbinical beard and Buddhist belly.´

One description of three lines suddenly added up to more than I had ever remembered about Ginsberg (right) in my fifty odd years of knowing his name.

´He had sung a duet with the Clash’s Joe Strummer on the song Ghetto Defendant from the British quartet’s latest album, Combat Rock, and now he was here as a kind of guardian angel for the controversial group´, Himes clarified.

´After all, for decades, Ginsberg, too, had been resisting hostility and convention even as he celebrated sensuality and invention. He produced his most famous poem, Howl, in 1955, the same year that three members of the Clash were born. His career had been a kind of creative crusade, and there he was at Pier 84, giving his blessing to the Clash as a continuation of that same bohemian movement.

Ginsberg was an inspiration for multiple musicians, from Bob Dylan to Patti Smith, but his crucial role in late-20th century Anglo-American music is often overlooked.´

So now I was already hooked and wanted to know more. I was already vaguely aware of his sphere of influence but why is Ginsberg suddenly again a person of interest and why was Himes writing about him again recently?

As if having his own Google-like anticipation of my next question, Himes started offering answers.

´Two new albums shine a welcome light on Ginsberg´s contributions,´ he responded. as if I had asked him my questions out loud.

´The first´, he said ´is The Fall of America—A 50th Anniversary Musical Tribute, which includes a selection of verse and out-takes from Ginsberg’s 1973 book, (The Fall Of America: Poems of These States, 1965-1971), set to music by members of the Grateful Dead, the Fugs, Sonic Youth, the Handsome Family, the Virgin Prunes and Yo La Tengo as well as Devendra Banhart, Bill Frisell, Andrew Bird and Angelique Kidjo.´

In a way that just doesn´t happen in books like All You Need To Know About Everything, Geoffrey offered me not one but two signposts down sidetracks & detours to places I was familiar with in Grateful Dead and The Handsome Family. I was beginning to think I and this Ginsberg bloke might have mutual friends.

´The other album, ´said Mr. Himes, bringing me back on point, ´is Allen Ginsberg at Reed College—The First Recorded Reading of Howl and Other Poems, and it delivers just what its title promises. Ginsberg’s legendary first public reading of Howl took place at San Francisco’s Six Gallery in October on October 7, 1955. In the audience were Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Neal Cassady, and they immediately recognized the historic nature of the evening. Kerouac described the event in his novel Dharma Bums, and Ferlinghetti published the poem the following year in his City Lights Pocket Poets series—and got William Carlos Williams to write the introduction.

No one taped the reading, however, and it wasn’t until Ginsberg and Snyder went to the latter’s alma mater, Reed College in Portland, Oregon, that the poem was recorded on Valentine’s Day, 1956. Drained by the energy required by the cathartic poem, Ginsberg quit after the famous Part I. But that passage plus seven other early poems capture the poet before he had published a single book, in the first flush of inspiration, on the cusp of a great career. Strummer was not yet four years old, while the Clash’s Mick Jones, Paul Simonon and Topper Headon were not yet one. Terry Chimes, the Clash’s original drummer and back in the band at Pier 84, hadn’t even been born yet.´

Himes gives the historical time checks real specificity for me when he goes on to say ´the year of Howl’s debut, 1955, was also the year that Elvis Presley signed with RCA Records and went from being a regional phenomenon to a national force.

´The year of Howl’s publication, 1956,´ he added, ´was the year James Brown had his first R&B hit, Please, Please, Please. Obviously, something was in the air, a new generation’s dissatisfaction with the conformity, segregation and patriarchy they had inherited.

The poet’s words were as shocking and transforming as the two singers’ music. Just read for yourself—or, better yet, listen to—Howl with its long, Whitmanesque lines, its nouns and adjectives crammed together by shedding most of the conjunctions and prepositions, its mix of gritty/quotidian realism and religious/hallucinogenic visions, its critique of the present and its imagining of a better future.´

So, the Whitman reference suddenly placed Beat poetry amongst poetry more recognisable to me and I know a thing or two, maybe too much, about writing long lines, so I read Himes´ words I was simultaneously becoming more receptive to Ginsberg´s. At just the right time, Himes inserted an excerpt from Howl.

¨It begins,´ he said in an ´are you sitting comfortably, then we shall begin Watch With Mother kind of way, ´with one of the most memorable openings in 20th century literature:´

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night, who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat up smoking in the supernatural darkness of cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities contemplating jazz,…

What a wonderful line on which to close your extraction, Mr Himes !

´With nothing to accompany his speaking voice, Ginsberg achieved much of the same impact as the early rock ’n’ rollers:´ The writer for Paste then claimed.

´(His work shared) the same thrilling defiance of authority, the same thrilling celebration of bodily pleasures. If the rebellion of Presley and Brown was primarily musical, Ginsberg’s was primarily verbal—and it wouldn’t be till Dylan went electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival that those two streams came together. Poetry gained a new power when yoked to song, but so did song. Pop music is a coupling of language and sound, so why shouldn’t the former be as ambitious as the latter?

Even though Ginsberg presented his pieces on the page and in solo readings, music was always implicit in his work. On the First Recording album, for example, he explains his theory of the “bop refrain, chorus after chorus after chorus, the idea being, say, Lester Young in Kansas City in 1938 blowing 72 choruses of ‘The Man I Love’ till everyone in the hall was out of his head and Young also.´

Once again the pilot ship Himes had led me back into familiar waters with his Lester Young reference.

It was in this reference, Himes pointed out ´to the Count Basie Band’s tenor saxophonist (also an acknowledged influence on Kerouac) reveals the crucial role of syncopation and sustained improvisation in the creation of Ginsberg’s poetry. When he starts reading Howl, you can hear that jazz quality in the pattern of accents and pauses and in the propulsive momentum of the lengthy lines.

So it makes sense that Ginsberg recognized Dylan as his artistic heir. In D.A. Pennebaker’s 1967 documentary, Don’t Look Back, there’s Ginsberg in the alley behind Dylan, who presents the lyrics to the Ginsbergesque Subterranean Homesick Blues on a series of poster boards. In the 2019 film, Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese, Ginsberg is a supporting character, performing with Dylan for a room of American Indians and communing with Dylan at Kerouac’s grave.´

By now I had a favourite jazz artist or two, Dylan and his poster-boards, the wonderful but weird Pennebacker filming and the Scorsese cinematic/poetic epic as well as Kerouac´s grave to put on to my mental image of a Sergeant Pepper-like collage of Ginsberg and his hero and acolytes.

´When you get old is when all your dreams come true,´ Ginsberg told Himes in a 1977 interview, “if you have the right dreams. When I was younger, I always wanted to go out on a rock ’n’ roll tour. When I got to be 50, I went out on a rock ’n’ roll tour.´

That was a reference to the Rolling Thunder tour the year before.

Himes continued in his article about how ´when Phil Spector was producing Leonard Cohen’s The Death Of A Ladies Manin 1977, he cajoled Dylan and Ginsberg into singing harmony on Don’t Go Home With Your Hard-On.´

Himes also reminds us that ´Patti Smith recorded the Ginsberg song, Spell, on her Grammy-nominated 1997 album, Peace And Noise. At one point, Ginsberg was taking guitar lessons from Dylan. He had already been accompanying himself on the harmonium, a miniature pump organ, during his reading and later travelled with a guitar accompanist. So it makes sense that a wide range of musicians would want to contribute to The Fall of America—A 50th Anniversary Musical Tribute.´

Even when he refers to some of the artists who contributed to these two albums, Geoffrey begins with a reference to The Handsome Family, an alternative country and Americana duo consisting of husband and wife Brett and Rennie Sparks formed in Chicago, Illinois, and as of 2021 based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. They are perhaps best known for their song Far From Any Road from the album Singing Bones, which was used as the main title theme for the first season of HBO’s 2014 crime drama True Detective. The band’s 10th album, Unseen, was released on September 16, 2016, the first new release on the band’s own label Milk & Scissors Music and through long-time label Loose in Europe.

Himes speaks of how ´The Handsome Family set Ginsberg’s voice reading the middle section of Hiway Poesy: L.A.—Albuquerque—Texas—Wichita to an Americana reverie of pedal steel, theremin and twangy guitar. Thus the details of this road trip across the American West (the Rockies rising as ´icy tipped distant earth peaks over hilltops,´ a power plant casting ´endless iridescence on black velvet desert´,) are reinforced by the music. And when the poet begins chanting Hindu sutras, the musical contrast is as vivid as the cultural contrast must have been in the car.

Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart composed and recorded a brooding synth track under Ginsberg’s reading of First Party At Ken Kesey’s With Hell’s Angels. The ominous music reinforces the poem’s tension between young people dancing to Ray Charles and the Rolling Stones on the hi-fi, and the police cars parked outside the gates of this home in the redwoods. In his liner notes, Hart points to Kesey as the link that brought the beat culture of the fifties together with the hippie culture of the sixties, Ginsberg with the Dead. And once again, Ginsberg’s fascination with popular music is explicit.´

(Photo by Chris Felver/Getty Images)

Why wasn´t One Flew Over The Cuckoo´s Nest prescribed by my teachers as compulsory reading for my class of 1967 when I was fifteen? We kids from council estates all over Prestwich and Whitefield´s Manchester overspill were instead being made to read Thomas Hardy and the Brontes !

Himes goes on to say of Ginsberg´s work and these recordings that ´many of these poems are travelogues of crisscrossing the nation. Yo La Tengo’s seething synths sneak up under Ginsberg’s eight-minute reading of Bayonne Into NYC, which evokes North Jersey of 1966 with Springsteenian detail.´

I´m beginning to feel right at home with these guys and even pretty contemporary when Himes mentions how ´The Denver-raised jazz guitarist Bill Frisell provides a prickly, sparkling solo-guitar soundtrack for Ginsberg’s reading of Over Laramie, the description of a plane flight through a rainstorm over Wyoming and Denver, the weather as wondrous and terrifying as the music.

Andrew Bird takes a different tack; he sings the words himself rather than relying on a Ginsberg sample. “Easter Sunday”´´ is a lovely celebration of a snow-melting spring day on a farm in the woods, and Bird sets the text as a bouncy, whistling, old-time country song. The Virgin Prunes singer Gavin Friday also handles vocals himself on Death On All Fronts, a night-time meditation on our planet poisoning itself, and the music by Scottish trip-hop producer Howie B is as chilling as the language.

Ginsberg himself was a mediocre singer and instrumentalist, not that that stopped him from doing both in public appearances. Eventually he hired accompanists, such as guitarist Steven Taylor, who contributes to The Fall Of America. Ginsberg’s best music, though, was in his written language, so full of rhythm and melody, and his attitude, which embraced popular music as a vehicle for poetry.´

Ginsberg himself once told Himes in an interview that ´the oldest poetry is chanted. Most poetries have always been connected with chant and music until the invention of the printing press. But that was only temporary—400 years—that’s a small bit of time. You take someone like Iggy Pop (left) or Mick Jagger, and you have poetry and music and dance together. Even Dylan dances a bit. So the ideal combination is the Bardic-shamanistic, poetry-dance music.´

With this article I realised I have as much to learn from Geoffrey Himes as writer of prose as I have to learn about the writing of beat poetry from Ginsberg.

With a couple of well-chosen quotes, a perfectly selected extrapolation and half a dozen perfectly picked pieces and one liners and by introducing me to familiar like-minded people like Springsteen and Dylan and Grateful Dead he had made me feel comfortable in the middle of the classroom. And it was a prefect lesson. I didn´t have to do any reading or writing, but simply had to listen to an expert enthusing about his passion.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!