VISIONS OF SIN: part 4 of Sidetracks & Detours Dylan week

VISIONS OF SIN:

By Norman Warwick

I had emigrated to take up residency here on Lanzarote only a month earlier when I watched in horror the on-line news footage that showed that I had lost the thousands of books and cds I had left in the not so capable hands of my brother.

It wasn´t his fault I suppose. He was helpless as the rest of us. However, perhaps if we had listened to Bob Dylan when warned The Levee´s Gonna Break, maybe my entire collection of music and literature wouldn´t have floated off to a watery grave in that terrible flood in 2015. I then added insult to my injury by lending one of only a handful of books I had brought over here to a lady from the Lanzarote creative writing group I had just joined. Five years later the group disbanded and I have never been given back that book.

´That book´, Dylan’s Visions of Sin, was written by Christopher Ricks who had already written deep examinations of the works of several canonocal poets. This book I loaned out was a stimulating study which I am sure I would now still be using as a reference book, with a fresh appreciation for the singer-songwriter’s genius, because I am so much enjoying studying (ie releasing flights of fancy) about Dylan´s new album Rough And Rowdy Ways, particularly looking at the track Murder Most Foul

As the title Dylan´s Vision Of Sin might suggest, Ricks sees Dylan as an essentially moral or religious songwriter, an artist who raises fundamental human questions about belief, behaviour, and values in his songs, and the structure of the study follows this view.

I, too, see Dylan as someone who raises questions much more often than he submits answers.

The first two chapters set up the framework within which Ricks will discuss Dylan. The first chapter, “Sins, Virtues, Heavenly Graces,” lays out Ricks’ central understanding that Dylan writes songs ´in which sins are laid bare (and resisted), virtues are valued (and manifested), and the graces brought home´. In particular, Ricks argues, these songs often exemplify the seven deadly sins, the four cardinal virtues, and the three heavenly graces of religious belief.

In a manner that reminds me of the clip, in Dead Poets Society, that has students measuring, on a graph, the quality of a poem, the second chapter shifts from the content to the complex form of Dylan’s poetry. Ricks explains the tools of poetic analysis he employs, as he undertakes the examination not only of rhyme and rhythm but also of the linguistic devices of alliteration, assonance, consonance, and so on, as well.

Ricks, in short, discusses Dylan the same way his readers will recognise from his studies of Milton, John Donne, Eliot, and other poets he has written about in the previous forty years. He sees Dylan’s songs as carrying messages of ethical and religious significance, and having satisfied himself that the usual and expected content is present and correct he then checks their form for evidence of the nuance and complexity demanded of any serious poet, by any serious reader. In more than five hundred pages, Ricks subjects Dylan’s lyrics to exhaustive and penetrating examination.

The plan of the book follows this fundamental view of Dylan’s work.

Seven chapters cover the deadly sins of envy, covetousness, greed, sloth, lust, anger, and pride, and each chapter usually includes analyses of a handful of Dylan’s songs, both the substance of their messages and the subtleties of their expression. (In one case, Ricks asserts that there are no songs of any kind about greed in Dylan’s opus—and writes several pages wondering why).

Each song analysis can run from ten to fifteen pages, and each page usually contains in addition several footnotes to other poets (regularly Donne; Alfred, Lord Tennyson; and Gerard Manley Hopkins) to biblical passages or to other studies of poetry. These pages only serve to justify Ricks’ formalised elevation of Dylan to the pantheon of poetic art, an elevation we might feel was subsequently confirmed with Dylan being awarded the Nobel Prize For Literature

The second third of the book contains chapters on the four cardinal virtues (justice, prudence, temperance, and fortitude), and the last third covers the three heavenly graces (faith, hope, and charity), and these seven chapters contain examinations of some of Dylan’s best-known songs.

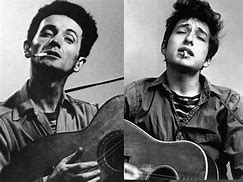

The appendices list some 170 Dylan song titles Ricks mentions or considers, of the five hundred or so Dylan has penned, and he probably only fully examines a quarter of those fully in this study, from Song to Woody in 1962 through Mr. Tambourine Man in 1964 to Hurricane in 1975 and Handy Dandy in 1990. Most readers will certainly complete their reading of Dylan’s Visions of Sin with a new understanding and appreciation of the song writer´s genius. For all that the writing is scholarly I think, too, that those readers would find it a pacier and more accessible read than they might have feared.

The heart of the study lies in the analyses themselves, and these are the best place to see what Ricks has accomplished here. His first full-scale discussion under ´envy´ is of Song To Woody, which appeared on Dylan’s first album in 1962 (one of only two songs Dylan himself penned on that album), and which is, of course, a tribute to the legendary folksinger Woody Guthrie (seen above, with Dylan) and Ricks findings and revelations might astonish some readers.

published by Sidetracks & Detours contributor

Andrew Moorhouse

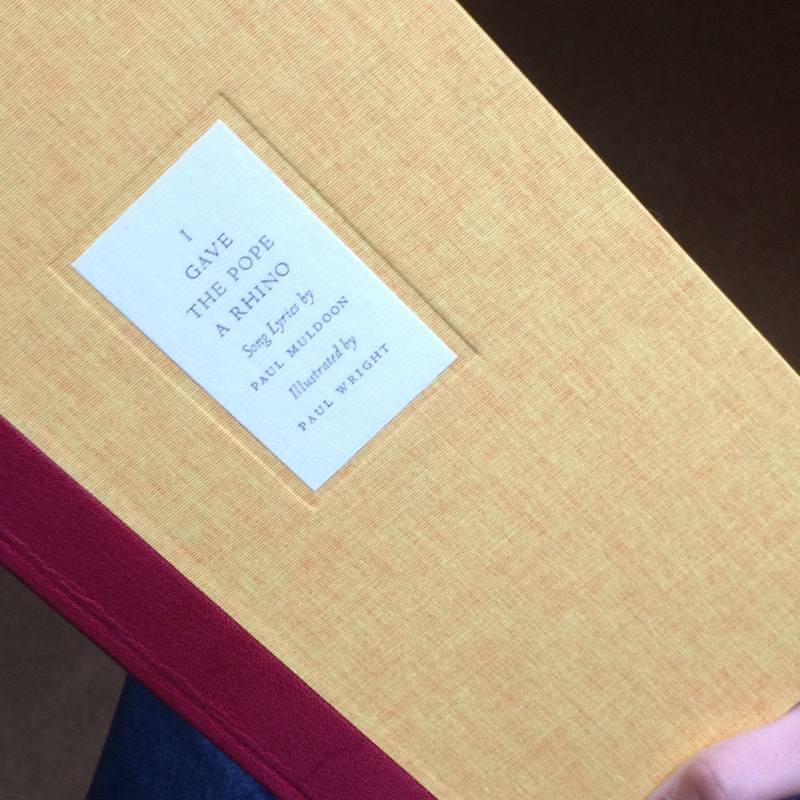

Bob Dylan is, these days´, rock’s equivalent of James Joyce, with his singular and continuing body of work increasingly picked over by academics and biographers. There has been, for instance, the publication of a collection called Do You, Mr Jones?: Bob Dylan With The Poets And Professors in which, of the former, it was writerspoets like Simon Armitage and Paul Muldoon, who made much more sense of Dylan’s work than did the Professors.

This perhaps emanated from artistic empathy, or it may be that poets sense what scholars seem to have trouble accepting: Dylan is a singer-songwriter first and foremost. His poetry is not the whole, but is a part, contained in within, but not by, his art: his work isa convergence of melody, line, turn of phrase, nuance, drawl, and, famously, electricity. His one book of published prose, the amphetamine-fuelled fragments that make up Tarantula, makes the Beats look disciplined and restrained.

Interestingly, Christopher Ricks, the academic most associated with Dylan and formerly professor of English at Cambridge, and subsequently professor of humanities at Boston, is conspicuous by his absence from the list of Professors who contributed to Do You Mr. Jones?, Indeed, he was the brain behind the ‘Is Dylan Better Than Keats?’ about Dylan´s lyrics, which sparked briefly many years ago now, on Dylan’s lyrics, and which splutters on from time to time, usually when Dylan finds himself the bemused recipient of yet another honorary doctorate.

The Dylan/Keats question could only have been asked by an academic, and it forms the unstated subtext of Ricks grandly titled book, Dylan’s Visions of Sin. The strangest thing about the debate is that many see Keats as a mimic, a copyist rather than as a poet with originality in either content or form.

The title of the Dylan´s Vision Of Sin obviously suggests we should consider anger as one of the chief motivating force of Dylan´s writing, but here I think af Dylan´s contrariness of clarifying and closing down, of revealing and concealing and of constantly seeming to question his own answers.

He is a forever in search of that place where the truth lies.

Given the deep well he has to draw from, some might still wonder why is Ricks´ book such a frustrating read? Why do some critics, to put it bluntly, call it a mess? The answer, I think, is contained in The opening lines are, perhaps the least inviting introduction to a book on music: ‘Any qualified critic to any distinguished artist: All I really want to do is – what exactly? Be friends with you? Assuredly. I don’t want to do you in, or select you or dissect you or inspect you or reject you.’ A clever re-phrasing of all that Dylan Really Wants To Do, but a conceit for all that.

There are many critics, many not as high profile or as well rewarded as Ricks, perhaps, who suggest that what is wrong with that opening paragraph is what is wrong with this big, misguided book: it is too knowing, too clever, too clumsily conversational. Its tone lies somewhere between academia and what critics suspect the author thinks of as casually hip. It assumes too much – about the casual or curious reader’s knowledge of Dylan’s lyrics – and imparts too little. Not a great start for a book of scholarship.

It was said by one reviewer, that

´from the first page of the book Ricks dives headlong into Dylan’s lyrics, putting all his faith in close readings of the texts, and the texts alone. Dylan’s cultural context is paid the scantiest regard, likewise his development as an artist over four decades. Instead, the songs are rounded up, and shoe-horned into fitting the schematic model of the book. Thus, both the monumental – Like a Rolling Stone – and the relatively inconsequential – Day of the Locusts – are grouped under Pride, as if that tangential similarity were enough to illuminate them anew. Or, indeed, to illuminate us.

This scatter-gun approach is defeating in itself, but worse still is the style. Ricks quotes, for example, an uncharacteristically forthcoming Dylan on the writing of Positively 4th Street, which the singer says ‘is extremely one-dimensional… I don’t usually purge myself by writing anything about any type of quote, so-called, relationships’.

Ricks has since claimed that the writing Dylan´s Vision Of Sin was, a labour of love so it is painful to point out that some reviewers have felt ´defeated´ by its ungainly style. Perhaps it’s an academic trait, but Ricks seems unable, or unwilling, to write clearly and concisely for the benefit of the common, or indeed, informed reader.

I have some sympathy for Mr. Ricks, as I remember that on the bottom of the first essay I received back at University on my English Literature course, as a fifty year old ´mature´ student, were words written by my much younger professor:

´You write hideous, gargantuan sentences that I could never seem to get to the end of.´: not actually the most aesthetic sentence I´d ever read, but I took his point.

I´m sorry, readers, as I know I still have that trait but, whether despite it or because of it, I found Dylan´s Vision Of Sin by Christopher Ricks to be a free-flowing and enjoyable read.

And anyway, as the great Rick Nelson (left) once said at a Garden Party (a song in which he mentioned Dylan, don´t forget), ´you can´t please everyone, so you´ve got to please yourself´.

Lord knows, Dylan deserves a big book that takes his art seriously, but this tortured, tail-chasing exercise, for all its parading of literary awareness, seems not to be to the taste of everyone.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!