WORDS THAT LINGER AND WORDS WE LOSE

WORDS THAT LINGER AND WORDS WE LOSE

By Norman Warwick

Most of our readers will by now be familiar with the regular contributions made to these pages by Michael Higgins, who keeps us informed of current events on the literary scene around Rochdale in the North West Of England. So many of the elements of that opening sentence, however, might confuse some of those who actually know Michael in the real word beyond these pages. There is, indeed, much about Michael to confuse. He is, at heart, a local historian, often brushing the dust off ancient archives. He is too, however, part of a vibrant contemporary arts scene in the area that involves literary talks, literary festivals and poetry slams and readings. He is a fine writer, poet and lyricist and yet there is about him and his performances something of a medieval troubadour.

He is heavily involved with the Rochdale Edwin Waugh Dialect Society (EWDS), a group in thrall to Waugh in particular and to the works of his Northern peers. Many of the group members can read the nineteenth century poetry of Waugh, and others, in what sounds like the authentic dialect in which it was written, and some can even pen such poems in those tones too. Together, they are all dedicated to the preservation of old local dialect and to observation of new changes.

Edwin Waugh [1817-1890] was born in Rochdale, England in 1817. His family were working class and even when he managed to raise himself from his impoverished childhood roots he never forgot his roots. It formed the background for much of his poetry which was usually written in the dialect of the times.

Waugh (pronounced woff to rhyme with cough) was born in a small cottage in Rochdale, Lancashire, England in 1817. He was the son of a clog and shoemaker and the family, though working class, enjoyed a reasonable income. However, following the death of his father from a brain tumour at the comparatively young age of 37 when Edwin was only 7 years old, the family fortunes plummeted and for a time he and his mother lived in a cellar.

Perhaps because I was born and raised in Yorkshire and then moved to live amongst strange-sounding Lancashire folk I have always had a fascination with dialect. So I was excited by the opportunity, when taking my degree in English Language and Literature at The University of Leeds, (at the age of fifty in 1999), to study a module on dialect under the auspices of a leading expert in the field, Professor Clive Upton. Those of you who only speak proper English (like what I do) must trust me when I say enjoying a dialectic twang is a long, long way from the study of how language is pronounced and has changed with its glottal stops and dipthongs.

It was the most difficult subject I have ever studied and my marks and tutor-comments constantly reminded me of that fact.

I am reminded of all this by an article in the current University Of Leeds magazine which tells of how researchers from the University Of Leeds set out, in 1946, in search of ´old men with good teeth´ to take part in what was then the country´s most comprehensive survey of dialect and language. This unattributed article in the magazine describes how these researchers travelled up, down and across country to participate in a project that lasted more than thirty years. That England is a fertile landscape of language was made evident through a smattering of terms such as ´brunny-spots´, ´ferntickles´, ´murfles´, and ´summer-voys´, all of which were regional terms then in use to describe freckles. Such dialect variations were fastidiously recorded, first by hand in notebooks and then over the years on to cumbersome reel to reel tape recorders that had sometimes to be attached to a car battery if conversations were being held in remote villages without electricity.

Seventy and more years since that series of research began, the invaluable resource it created is about to be digitalised. This update is to be financed through National Lottery Funding, The Footsteps Fund and from individual University donors. Five partner museums will work alongside University of Leeds, to upload archives to modern formats.

The 1946 project began with a focus on older male participants but now this renewed survey will be open to submissions from all, of whatever age or gender or background. There is special interest in seeking evidence of existing dialects between the young and volunteers are asked to make new oral history recordings to accurately reflect dialect deviations across the UK, in an attempt to ´create a new cultural legacy for future generations.´

Three of those original interviewers who took part at the outset in 1946 have been tracked down and today´s researchers are now also keen to locate descendants of those who were interviewees in the project. Some children and grandchildren of original participants have already come forward,

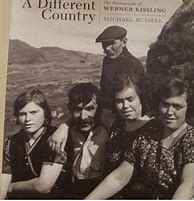

So, too, has Werner Kissling, the ethnographer and photographer who worked on the project in the nineteen sixties. Kissling and his camera captured images of typical artisanal work and social play of the era to accompany the words being unearthed. Thus he photographed sheep-washing and ´wallops´, a slight variation of the game of skittles, as well as images of ´bartle-burning´ a phrase used to describe the parading of straw-filled effigies through the village of West Witton, near Leyburn in North Yorkshire, before they were set alight.

Kissling was born as the third son to a wealthy, aristocratic brewing family. He served both in the army and the navy during the Great War, becoming a diplomat for the new Weimar Republic in 1919.

However the rise of the Nazism influenced his decision to resign from the German diplomatic service in 1931 to become a scholar and photographer. After developing links with Cambridge University, he undertook privately funded study of ethnology.

As a former German diplomat, Kissling was interned in the Tower of London and on the Isle of Man (1939 – 1942), although feeling only antipathy towards the Nazis and having been involved with the prosecution of Hitler.

In 1968 the impoverished Kissling moved to Dumfries where he collected traditional artefacts for the local museum. He only made one film but remained a keen still-photographer until he was almost ninety, recording many traditional rural crafts and ways of life in diverse settings. He also sold many photographs and negatives during his last 30 years of life with many examples of his work held in various collections. He was an extremely private man who wished no public recognition for himself or his work while he was alive. He died in 1988, and is buried beneath a gravestone reading SOLDIER, DIPLOMAT, SCHOLAR, GENTLEMAN

Dr. Fiona Douglas, of the school of English at the University Of Leeds, who is leading the current dialect-research project, says to its supporters that ´these amazing memories allow us to touch history and reach into the past.´

The University Of Leeds has also previously received funding from various grants through The National Lottery heritage Fund that have helped to unlock for sharing a number of cultural treasures. Some of the gifts supported the Marks In Time Exhibition, of material from the Marks And Spencer Archive. Similar donations have enabled the purchase of Sir Herbert Read´s vast collection of rare books, and helped create The Treasures Of The Brotherton Gallery, a public exhibition housed by the University of Leeds, rooted in Yorkshire and usually open to the world with admission to the Gallery is free to all. It is currently closed until further notice in these lockdown days, but is surely worth noting for a future visit. Furthermore, in the strange serendipitous ways of the arts we also hear rumours of plans to promote dialect awareness via the schools, that might involve peripatetic school visits from dialect practitioners, involving readings and exhibitions. We will keep you posted on these pages of nationwide developments, although these probably will now not occur until coronavirus difficulties ease.

Meanwhile, we should be grateful that organisations like the Edwin Waugh Dialect Society still exist in towns like Rochdale to preserve and savour old dialect. So, also keep your eyes on our sister pages at all across the arts in The Rochdale Observer, or on their own new aata blog pages, for further information about The Edwin Waugh Dialect Society.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!