ART AND SCIENCE UNITE

The worlds of arts and of medicine do not overlap very often, despite recent interesting developments in the UK such as the Poetry On Prescription scheme and Clinical Commissioning Groups having some monies in their budget available for buying in therapeutic arts interventions to boost individual and communal well-being, Even with these initiatives now fairly well established, it was still a surprise to see a recent article by Paul Glynn, the Entertainment and Arts reporter for BBC News, creating a cocktail of poetry and pills to tell of a commission by The Institute For Cancer Research.

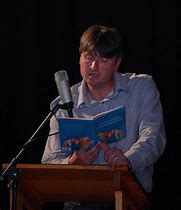

I was also immediately drawn to the story by the fact that it seemed to focus on Simon Armitage, the poet, writer and broadcaster. I studied creative writing under him at the University Of Leeds twenty years ago when he was much younger than I, as, indeed, he still is. I was also very privileged to have been given permission to deliver the first public reading a few years of Simon´s poem, Consider The Poppy. The piece was written to commemorate the hundredth centenary of the start of the First World War, and I read the work at a ceremonial event in Rochdale in 2014.

Appointed as our Poet Laureate in May of this year, Simon has had his latest work, Finishing It, micro-engraved on to the face of a replica cancer pill. Apparently the piece was commissioned by The Institute For Cancer Research and is intended to ´promote and celebrate work being delivered in the advancement of cancer treatment.

Simon describes his time in post so far as ´really exciting´ and said he feels comfortable delivering what is ´exactly the kind of project ´ he had in mind when accepting his appointment.

He follows names in the laureateship like Tennyson, Betjeman and Carole Ann Duffy and says this latest project ´is about a subject that affects most families at some time, and I´m very happy that the poem be used by The Institute in whatever way they want.´

He went on to say, ´I´ve only been doing this job, if you can call it a job, for a couple of months now, but this feels like the work I should be doing as a public poet.´

.He added that he is ´optimistic about the potential of medicine and of poetry.´

With as much care as the Football Association´s scrivener when engraving the name of Bolton Wanderers when next they win the FA Cup, the poet laureate´s words have been skilfully inscribed into a tiny facsimile of a cancer treatment tablet, measuring only 20 x 30 millimetres. Graham Short, with practiced precision, has carved the words of the poem on to a model for display in the Centre For Cancer Drug Discovery, scheduled for opening in 2020.

poet

Simon, from Marsden near Huddersfield in Yorkshire in the UK, told the BBC that he feels there is common ground in how the arts and the sciences ´try to figure out life´. Although acknowledging that he is ´not a scientist by any means´ the poet said he imagines that ´what goes on in those laboratories is as much about trying to imagine a future.´

He elaborated on how the idea of writing on a tablet has biblical Old Testament connotations. The tablets he was referring to were, of course, given to Moses and were supposedly written by God´s finger.

Simon could see the connection between biblical miracles and how finding a cure for cancer would be likened to them, but recognised that he couldn´t claim that such miracles could be delivered by a poem. However, he is confident that he can offer ´in the shape of a poem and in the shape of this little pill, this little magic bullet, is a kind of hope.´

Professor Paul Workman, CEO of The Institute Of Cancer Research, London, certainly sees this tiny reproduction of the poem as bearing comparison to methodology being followed under the microscope by leading scientists throughout the UK. The poem and its engraving ´perfectly convey the exquisite precision of the work ICR scientists will be conducting´ in the soon to be opened Centre For Cancer Drug Discovery, in the aim to create ´a new generation of cancer medicines.´

Simon Armitage thinks ´it seems inevitable´ that such research could bring an end to cancer as we know it.´ He explained that the question of the age is being reframed from being ´will we ever find a cure for cancer?´ into being a question of how we can manage cancer, and live with cancer, in the way that we now do with other illnesses.´ He suggests it might be that ´there is a philosophical aspect to this as well as a medical one.´

The poem itself seems to be fifteen lines, or fifty one words, of optimism and defiance, as perhaps captured by the final adverb ´brazenly´ and there seems to be so much of the vocabulary that reminds us of all aspects of the battle. There is the employment of ´sentence´ that at once reminds us of the particulars of the poetic form and of the ´sentence´ that cancer so often imposes. Similarly, the reference to a ´full stop´ sharply reminds of how decisive cancer can be but also looks ahead to when we might put a full stop to cancer´s tyranny. Finishing It seems self-referential in describing itself as ´the sugared pill of a poem´ and yet, clear in its words, and indeed, its title, is the fact that the poet is, indeed ´optimistic about the potential of medicine and of poetry´ to discover a way to manage the disease.

Perhaps we are being fanciful in suggesting it seems to have been etched, rather than written, with precision and exactitude, but it certainly feels as if every word has been rolled on the tongue in an attempt to match diction and definition and to test and balance every interpretation. Even the title of Finishing It invites us to consider what is the ´ít´ being referred to. Like the lettering on a silver trophy, or tiny tablet this poem is the work of a skilled craftsman. (see below).

Finishing it by Simon Armitage

I can’t configure

a tablet

chiselled by God’s finger

or forge

a scrawled prescription,

but here’s an inscription, formed

on the small white dot

of its own

full stop,

the sugared pill

of a poem, one sentence

that speaks ill

of illness itself, bullet

with cancer’s name

carved brazenly on it.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!