A KIND OF IMMORTALITY for Helen Reddy

A KIND OF IMMORTALITY?

Norman Warwick explores the career of Helen Reddy

Helen Maxine Reddy (25 October 1941 – 29 September 2020) was an Australian-American singer, songwriter, author, actress, and activist. Born in Melbourne, Victoria, to a show-business family, Reddy started her career as an entertainer at age four. She sang on radio and television and won a talent contest on the television program, Bandstand in 1966; her prize was a ticket to New York City and a record audition, which was unsuccessful. She pursued her international singing career by moving to Chicago, and subsequently, Los Angeles, where she made her debut singles One Way Ticket and I Believe in Music in 1968 and 1970, respectively. The B-side of the latter single, I Don’t Know How to Love Him, reached number eight on the pop chart of Canadian magazine RPM. She was signed to Capitol Records a year later

During the 1970s, Reddy enjoyed international success, especially in the United States, where she placed 15 singles on the top 40 of the Billboard Hot 100. Six made the top 10 and three reached number one, including her signature hit I Am Woman. She placed 25 songs on the Billboard Adult Contemporary chart; 15 made the top 10 and eight reached number one, six consecutively.

In 1974, at the inaugural American Music Awards, she won the award for Favourite Pop/Rock Female Artist.

On television, she was the first Australian to host a one-hour weekly primetime variety show on an American network, along with specials that were seen in more than 40 countries.

Between the 1980s and 1990s, as her single I Can’t Say Goodbye To You became her last to chart in the US, Reddy acted in musicals and recorded albums such as Center Stage before retiring from live performance in 2002. She returned to university in Australia, earned a degree, and practised as a clinical hypnotherapist and motivational speaker.

In 2011, after singing Breezin’ Along With The Breeze with her half-sister, Toni Lamond, for Lamond’s birthday, Reddy decided to return to live performing.

Reddy’s song I Am Woman played a significant role in popular culture, becoming an anthem for second-wave feminism. She came to be known as a feminist poster girl or a feminist icon. In 2011, Billboard named her the number-28 adult contemporary artist of all time (number-9 woman). In 2013, The Chicago Tribune dubbed her as ´The Queen Of Seventies Pop.´

Reddy’s stardom was really solidified, though, when her single I Am Woman reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 in December 1972. The song was co-written by Reddy with Ray Burton; the singer attributed the impetus for writing I Am Woman, and her early awareness of the women’s movement, to expatriate Australian rock critic and pioneer feminist Lillian Roxon. Reddy is quoted in Fred Bronson‘s The Billboard Book of Number One Hits as having said that she was looking for songs to record which reflected the positive self-image she had gained from joining the women’s movement, but could not find any, so ´I realised that the song I was looking for didn’t exist, and I was going to have to write it myself.´ I Am Woman was recorded and released in May 1972, but barely dented the charts in its initial release. However, female listeners soon adopted the song as an anthem and began requesting it in droves from their local radio stations, resulting in its September chart re-entry and eventual number-one peak.

I Am Woman earned Reddy a Grammy Award for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance.

At the awards ceremony, Reddy concluded her acceptance speech by famously thanking God ´because She makes everything possible´. The success of I Am Woman made Reddy the first Australian singer to top the U.S. charts.

Three decades after her Grammy, Reddy discussed the song’s iconic status:

´I think it came along at the right time. I’d gotten involved in the women’s movement, and there were a lot of songs on the radio about being weak and being dainty and all those sort of things. All the women in my family, they were strong women. They worked.

They lived through the Depression and a world war, and they were just strong women. I certainly didn’t see myself as being dainty,´ she said.

Over the next five years following her first success, Reddy had more than a dozen U.S. top-40 hits, including two more number-one hits. These tracks included Kenny Rankin‘s Peaceful (number 12), the Alex Harvey country ballad Delta Dawn (number one), Linda Laurie‘s Leave Me Alone (Ruby Red Dress) (number three), Austin Roberts‘ Keep on Singing (number 15), Paul Williams‘ You and Me Against The World” (featuring daughter Traci reciting the spoken bookends) (number 9).

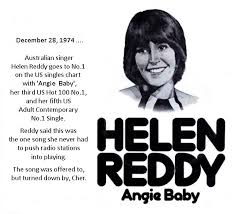

The song mentioned at the top of this article, Alan O’Day‘s Angie Baby, then reached number one, followed by Véronique Sanson and Patti Dahlstrom‘s Emotion (number 22), Harriet Schock‘s Ain’t No Way to Treat a Lady (number eight), and the Richard Kerr/Will Jennings-penned Somewhere In The Night (number 19) which, three years later, became a bigger hit for Barry Manilow.

On 23rd July 1974, Reddy received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for her work in the music industry, located at 1750 Vine Street.

At the height of her fame in the mid-1970s, Reddy was a headliner, with a full chorus of backup singers and dancers to standing-room-only crowds on the Las Vegas Strip. Among Reddy’s opening acts were Joan Rivers, David Letterman, Bill Cosby, and Barry Manilow. In 1976, Reddy recorded the Beatles‘ song The Fool on the Hill for the musical documentary All This And World War II.

Reddy was also instrumental in supporting the career of friend Olivia Newton-John, encouraging her to emigrate from England to the United States in the early 1970s, giving her professional opportunities that did not exist in the United Kingdom. At a party at Reddy’s house after a chance meeting with Allan Carr, a film producer, Newton-John won the starring role in the hit film version of the musical Grease, so Helen Reddy´s advice proved pretty well founded.

A bio-pic of Helen´s life was released earlier this year but met with some tepid reviews, such as the one at

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/oct/09/i-am-woman-review-helen-reddy

reproduced from The Guardian, as written by Peter Bradshaw,

´There´s a taste of turkey, or a can of own-brand mechanically reclaimed turkey-substitute, in this moderate TV-movie-style biopic of Helen Reddy,´ begins Mr. Bradshaw about the bio-pic of the Australian-born singer who came to the United States and had a string of hit singles in the 1970s, including the feminist anthem I Am Woman.

Reddy found her voice among the commercial shlock of the day (this film has at one moment a shot of Reddy’s place on the Billboard 100 list, one place behind Chuck Berry’s My Ding-a-Ling).

Tilda Cobham-Hervey gives a bland performance as Reddy; Evan Peters (Quicksilver from the X-Men movies) is hammy and over-the-top as the sweaty manager and husband, Jeff Wald, who snorts all Reddy’s earnings up his nose. Danielle Macdonald adds some zip with her performance as Helen’s friend, pioneering music journalist Lillian Roxon, whose personality is made more interesting here than that of the main character,

The sentiments expressed in the movie are laudable enough, but cardboard dialogue and clichéd storytelling make it a wearisome watch, and Cobham-Harvey’s performance is so opaque and uninflected it feels like a lost item of pop art. When the film shows Reddy performing Angie Baby during her Vegas residency – actually, a rather disturbing song – she just croons earnestly through the track pretty much in its entirety.

There is something so inert, uninterpreted and undramatic in this sequence that the film goes into a trance of pointlessness. Each scene needed a jolt of music or energy that just wasn’t there.´

I would agree with much of what Peter Bradshaw has to say, as it is certainly true that the project has emerged as being somewhat too reverential. Nevertheless the comments made by Director Unjoo Moon, who worked closely with Reddy on the film, reflected on their friendship and the condolences she offered to Reddy’s family were obviously very genuine.

Reddy’s inspiring life story in I Am Woman was directed by female filmmaker Moon and is from the producers behind The Sapphires, the 2012 movie starring Deborah Mailman, Jessica Mauboy and Chris O’Dowd.

When Moon met Reddy, at a ‘G’Day Australia’ event in Los Angeles in 2013, ahe was surprised to find that her personal story had never been told-

‘When I first met Helen Reddy she told me that I would be in her life for many years. What followed was an amazing seven-year friendship during which she entrusted me with telling her story in a film that celebrates her life, her talents and her amazing legacy,’ Moon said of working on Reddy’s only authorised biopic. ‘She will always be a part of me and I will miss her enormously.’

‘I will forever be grateful to Helen for teaching me so much about being an artist, a woman and a mother. She paved the way for so many and the lyrics that she wrote for I Am Woman changed my life forever, like they have done for so many other people and will continue to do for generations to come,’ she said.

´On behalf of all of us involved in making the film I Am Woman, producer Rosemary Blight and I extend our condolences to Helen’s family especially her children Traci and Jordan, her granddaughter Lily and her ex-husband Jeff,’ Moon concluded.

Helen had actually penned her own, perhaps too soon, memoirs which were published in book form as The Woman I Am. in 1973, and Sarah Ferrell wrote a comprehensively damning review of the work for The New York Times.

´Is Helen Reddy a person of unorthodox beliefs, or a crackpot?´ was the opening question which set the tone for the rest of Gerrell´s review, as she answered her own question with, Whichever, her memoir, The Woman I Am, belongs right up there with the collected works of Shirley MacLaine.´

Best remembered as co-writer and performer of the 1972 hit “I Am Woman” (hear me roar), Reddy grew up in a canonically dysfunctional family that put her on the Australian stage when she was a tyke. When not touring, the family was based in Melbourne, where, as an 11-year-old student at the Tintern Church of England Girls Grammar School, Reddy had what was perhaps her first out-of-body experience. She was thereby forever convinced of the immortality of the soul.

Unlucky in love, Reddy has had three husbands, to whom she refers by number rather than name: One was an alcoholic; Two, she says, was a substance abuser who acted as her business manager, stole her money and involved her in a vicious child-custody fight; and Three barely figures in the narrative.

It was on an Asian tour (with Three, as it happens) that Reddy realized she “had truly achieved my dream of an international career.” Alas, she was least successful in Australia, although, as she says, “it was hardly my fault if Australian radio chose not to play a lot of my hits.” Australian newspapers did pay attention: they picked on her for having a swelled head. They were really annoyed when, in the 1970’s, Reddy decided to become an American citizen.

Reddy, who had done considerable research into her own family background, was a founding member of the Tasmanian Genealogical Society and sufficiently expert in the field to have been a guest speaker at the Mormon Church’s 1991 International Genealogical Congress. Her other great and continuing interest was the study of matters metaphysical, particularly reincarnation and past-life regression, which she finds compatible with family history.

This has brought her to some pretty startling conclusions about other people’s family trees.

Reddy is a subscriber to the notion of group karma, which “involves several people — often family members but not necessarily in the same configuration — reincarnating together to resolve unfinished business, so spouses might reincarnate as siblings or vice versa.” She applies this to, among other things, the British royal family, in which she takes an almost unhealthy interest. (See her take on Princess Diana, saint and martyr.)In a not-to-be-missed chapter entitled Royalty And Reincarnation, Reddy, having dropped the bombshell that Wallis Warfield Simpson, Duchess of Windsor, was the reincarnation of Richard III, provides a chart of the dramatis personae surrounding the abdication of Edward VIII to demonstrate that it all goes back to the Wars Of The Roses. Wallis (or Richard), it seems, had a soul mission to atone for the murders of the little princes in the tower and to see that the crown was returned to its rightful heirs. Edward, Duke of Windsor, was once Richard’s personal servant (he is given no name) and can again doggedly devote himself to his monarch once Wallis has arrived on the scene. The little princes are, of course, Queen Elizabeth II and Princess Margaret. And, in the same chapter, Elvis was King Tut.

By 2001, the year she turned 60, Reddy had decided to look for a new career in the helping professions. Led by a more than usually complicated system of signs and portents, she took up training as a clinical hypnotherapist. And there she remained for life, happily, one hopes, curing others of their psychic ills.´

Nevertheless, An apparently ineffective, if well-intended bio-pic and a seemingly immature ´memoir,´ savaged by a sharp, articulate journalist, should not be enough to dilute a singing career that won popular and critical acclaim around the world, I never met Helen Reddy, and was not even fortunate enough to even see her in concert. Nevertheless, down the radio waves she somehow left a record, Angie Baby, on the jukebox of my mind that has stayed with me over forty years. Whether any other singer could have had that same impact with that song who knows?

What I do know is that because of, at least, one great song Helen Reddy is one of those stars who, even in death, will remain forever on my playlists.

Isn´t that a kind of immortality?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!