When Canadian musicians started a revolution SOUTH OF THE BORDER

When Canadian musicians started a revolution

SOUTH OF THE BORDER

by Norman Warwick

I look back to when I was one and twenty, as A E Housman would have had it, and feel sure I was in my salad days. I had fallen in love with a generation of songwriters and was enjoying the folksy, pastoral music that was a gentler sibling of rock. We had a stereophonic recording player that was like a piece of furniture and it had a sliding door over the turntable and I often tried to squeeze my head into the cabinet so that I could hear, even better, the fierce emotions wrapped in such laid back and softly sung arrangements. When I married and had a home of our own I was enjoying listening to how this generation of Canadian songwriters began to influence the writers who would forge what we now call Americana.

I was living in tranquil times and, until Paste magazine, in the shape of the old curmudgeon Geoffrey Himes reminded me, and all his readers, that whilst I thought I was living in quiet, peaceful era, I was in fact living through, and maybe was even a part of, a not always peaceful revolution. Himes hasn´t quite convinced me that it was a revolution but it was certainly a musical era of galloping evolution.

Nevertheless Geoffrey´s recent article in Paste on line reminded me that when English acts such as the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Kinks and The Who revitalized rock ‘n’ roll in the early ‘60s, and took their music racing up the American Billboard charts they earned the name of the British Invasion.

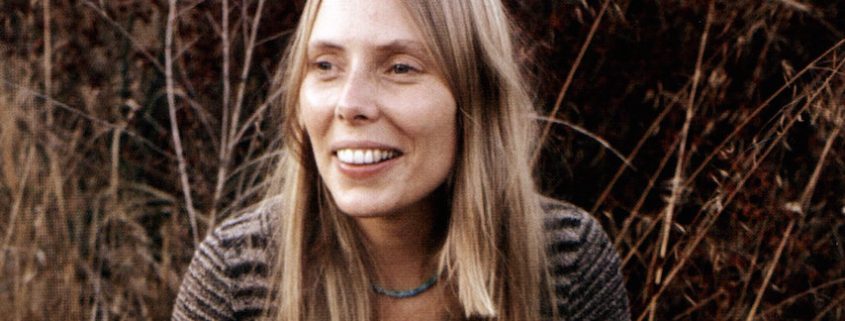

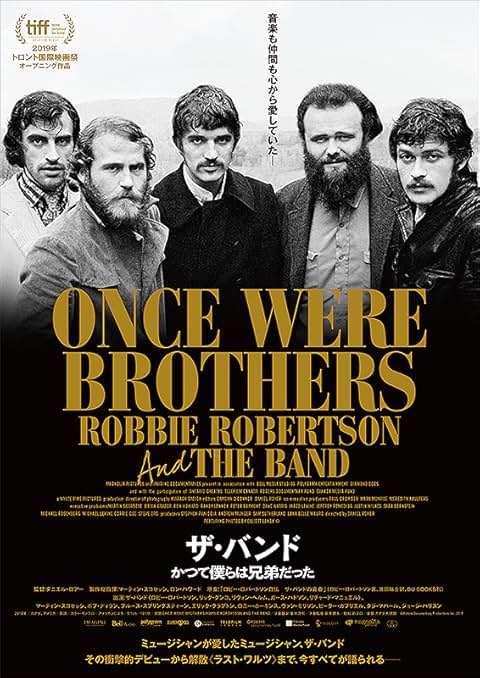

So why didn’t north-of-the-border acts such as Neil Young, Joni Mitchell (left) and the Band, who did something similar in the early ‘70s, earn the name of the Canadian Invasion? I was intrigued by Mr. Himes question, especially as I knew it would prove rhetorical and that the answer would soon be revealed.

Some rock historians portray the pre-punk portion of this decade as a rock ‘n’ roll wasteland—a view that Himes believes is only possible if you ignore the work of these Canadians.

He submits in evidence the crucial contributions as this immigrant influx continues to pour out of the vaults. Released in 2020, the 10-CD box set, Neil Young Archives Volume II: 1972–1976, documented Young’s twin impacts on the early ‘70s as both a solo-acoustic singer-songwriter and as the leader of the rock ‘n’ roll band Crazy Horse. Released this fall, the 17-CD, five-Blu-Ray box set, Neil Young Archives Volume III: 1976–1987, continues the story into the next decade.

In similar fashion, 2023’s six-CD box set, Joni Mitchell Archives – Vol. 3: The Asylum Years (1972–1975), expanded on her most popular and influential music with outtakes and live performances. This fall, she followed that up with Joni Mitchell Archives – Vol. 4: The Asylum Years (1976-1980), which does the same with her most ambitious and experimental music. It begins with seven songs from her brief tenure with Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue in 1975 and ends with 23 songs from her 1979 tour with an all-star jazz band including Herbie Hancock, Pat Metheny and Jaco Pastorius.

The Band is represented by the 27-CD box set, Bob Dylan: The 1974 Live Recordings. The Band’s own sets during that tour are not included, unfortunately, but they are the backing band on all the Dylan performances except for the solo-acoustic mini-set he did each night. Of the 431 tracks, 417 are previously unreleased. Robbie Robertson, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson, Rick Danko and the Canadian band’s only American, Levon Helm, were the best backing musicians Dylan ever had, something that’s obvious in the muscular, lyrical, ever-shifting arrangements of these songs.

Both of these invasions benefitted from loving American music at a distance. Because they didn’t actually live in the U.S. as teenagers, John Lennon, Joni Mitchell and the others heard the records imported from the States as pure music, not as signifiers in the nation’s racial and class divisions. They could hear the soulfulness in both Muddy Waters and Bill Monroe without worrying about which camp each artist was representing.

Furthermore, when these English and Canadian youngsters tried to play these songs themselves, there was no one around to insist that they do it the right way. As a result, they were able to play American songs wrong enough to come up with something original. And it was the creativity of that wrongness that enthralled American audiences when they heard their own music played back to them.

Young, the son of a Toronto sportswriter, was entranced by both the electric guitar of Chuck Berry and the acoustic guitar of Johnny Cash. Try as he might, however, he couldn’t quite sound like either of them, thanks to his adenoidal tenor and his slow but melodic way around the guitar. He formed a rock’n’roll band called the Squires and then went solo as a folk singer-songwriter. He brought both interests with him when he moved to Los Angeles in 1966 and co-founded the Buffalo Springfield with Stephen Stills and Richie Furay.

10 years later, when this new box set begins, Young is a star who still alternated between amplified-band dates and solo-acoustic gigs. You can hear him juxtapose the two on the first disc, a previously unreleased March 11, 1976, concert in Tokyo, which begins with seven singer-songwriter folk songs and finishes with seven songs with the world’s greatest garage-rock band, Crazy Horse. What carries over from one set to the next is the tunefulness of the guitars and the yearning of the vocals.

Among the box set’s more interesting segments is an unreleased 1977 home recording with Young playing new songs for Linda Ronstadt and Nicolette Larson. By the end of each song, they’re singing along, in a tentative but charming way. There’s an unreleased live show with Young backed by Devo, the rehearsals with Nashville string players for the Comes a Time album and a set of 1987 solo-acoustic song demos. The box set contains 28 hours of music; the press release boasts that you could listen to it as you drove from New York to Denver and still not hear it all. Of the 198 tracks, 121 are previously unreleased live versions, alternate takes or remixes. Fifteen songs have never been released before in any version.

Most of these are so slight that they were left unreleased for good reason. Exceptions include “Cryin’ Eyes,” a simple but irresistible rocker performed with Young’s Santa Cruz band the Ducks; “My Boy,” the plaintive plea of a father to his son performed live, backed only by Young’s banjo and harmonica; “Time Off for Good Behaviour,” a country two-step about the survivor’s guilt one feels when a friend’s in prison; and “Road of Plenty,” a seven-and-a-half-minute fable about encounters on a highway, played live with Crazy Horse.

A couple of years later Joni Mitchell invited members of two successful pop-jazz bands, the Crusaders and Tom Scott & the L.A. Express, to back her in the studio.

Her songs hadn’t changed much, even as her arrangements had acquired jazz ambitions. On 1975’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns, she began to address that discrepancy, stretching out the length of her lines and her verses to accommodate her modernist, stream-of-consciousness prose poems, even as her choruses were shrinking to mere refrains. There was a trade-off here. She gained a verbal and musical elasticity, flexible enough to handle a variable number of syllables and notes. But she sacrificed her gift for melodic hooks and aphorisms that made her earlier songs so arresting.

The initial changes were documented in Mitchell’s Archives—Volume 3: The Asylum Years (1972-1975), and Volume 4 picks up the story as she dives deeper into jazz, altering her song-writing as well as her arrangements. After the Rolling Thunder songs, the set’s first two discs present 25 songs from her February 1976 tour with Scott’s L.A. Express, with an emphasis on songs not included on Miles of Aisles, that fall’s live album from the tour. The band adds a welcome virtuosity and complexity on the hook-anchored early songs but struggle to sustain interest in the newest songs, especially the tunes she’s road-testing for her next two albums: Hejira and Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter.

At a Boston show, Mitchell sings a medley of “Coyote” and what she describes as its sequel, “Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter.” Both were unreleased at the time, and they do share a musical DNA. But while “Coyote” boasts a catchy, two-line refrain to focus its lively tale of a road-trip adventure, “Don Juan” is all verse and no real chorus, as flat as the Canadian prairie, an opera recitative without an aria for contrast.

Unlike the Young box, which mixes released and unreleased tracks, Mitchell’s is all unreleased or very rare: live tracks, demos and studio outtakes. Some of this is fascinating—a version of “Black Crow” with T-Bone Burnett’s Rolling Thunder Review band and a 12-minute piano improvisation in search of the music that would become “Paprika Plains”— but much of it is not.

Things changed when Mitchell later received an invitation herself, this one from jazz legend Charles Mingus to write lyrics for his music. The composer’s compact architecture and sturdy melodies help her sharpen her lyrics. The collaboration gives Mitchell an entrée to a higher tier of jazz musicians: pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Jaco Pastorius, guitarists John McLaughlin and Pat Metheny and saxophonists Wayne Shorter, Gerry Mulligan, Michael Brecker and Phil Woods. These players never play a song the same way twice, and that makes these live and alternate versions mesmerizing.

The Band backed Bob Dylan on two momentous tours: a 1966 trek across North America, Europe and Australia and a 1974 sequel across North America. The former was a contentious affair with audiences split between those booing the singer’s shift from folk music to rock and those celebrating it. The tension yielded Live 1966, my favorite rock ‘n’ roll album of all time, documenting the notorious shout of “Judas” from an aggrieved audience member in Manchester, England, a cry that triggered Dylan’s command to his musicians, “Play fucking loud.” They responded with a savage version of “Like a Rolling Stone” for the ages.

The 1974 tour was the victory parade. Dylan’s rock ‘n’ roll persona had long been embraced, and his backing group, the Hawks, had renamed themselves the Band and had made some of the finest music of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. They played to huge, enthusiastically unified crowds that initiated the custom of raising burning cigarette lighters overhead before the encore. The triumph may have reduced the drama, but it didn’t reduce the high standards of the music.

As it did for the 1966 tour, Columbia/Legacy Records has collected all the acceptable tapes from the 1974 tour into a 431-track, 26-disc box set. It includes all of Dylan’s solo-acoustic and amplified-band sets from those shows, but, sadly, not the Band’s sets on its own. Moreover, like the 1966 tour, the 1974 set-lists didn’t change much from night to night, leaving us to listen for subtle differences. They’re there, but it’s not clear the rewards justify the hunt for any but the most devoted Dylanophiles.

All these box sets require a lot of time and money, of course, but there are shorter, cheaper alternatives. Young has released Takes, a two-LP sampler of one track apiece from 16 of the 17 discs, including three unreleased songs and 12 unreleased versions. Mitchell has released a four-LP, 40-track vinyl set, Volume 4 Highlights, which contains her favorite moments from the 6-CD, 98-track version. Bob Dylan and the Band have released Highlights, a three-LP set that includes all the songs played on the 1974 tour that weren’t included in that year’s live album from the tour, Before the Flood. All these reissues provide a deeper dive into the 1970s, a decade when so many British and American acts from the ‘60s had exhausted their initial burst of inspiration, a decade that would have been so much duller if not for the Canadian Invasion.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!