KRISTOFFERSON

Geoffrey Himes on KRISTOFFERSON

He Helped Us Make It Through the Night

read by Norman Warwick

Maybe Kristofferson didn’t enjoy a long, productive musical career like Willie Nelson and Bob Dylan, but he wrote a handful of songs that will endure forever.

In the UK, we divide our top Premier League Goalscorers into two categories; those who are great (prolific) goalscorers and those who are scorers of great goals. If I were picking tracks for my music playlists Kristofferson would definitely be in that category of being a scorer of great goals. I am not sure I could find twenty songs to make a Kristofferson playlist but his top five songs would always be in the top ten of any self penned tracks of any recordings ever made, and on any given day Me And Bobby McGee, Sunday Morning Coming Down and Help Me Make It Through The Night could easily be my top three.

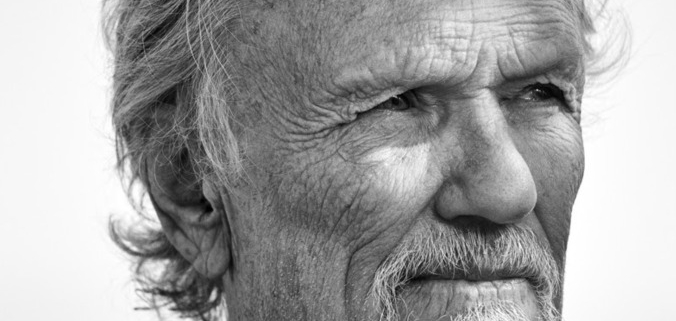

Kris Kristofferson, who died Saturday at age 88 in Maui, Hawaii, had not one but two successful careers: the first as a country-music songwriter and the second as a movie actor.

But, says Mr Himes, he probably wouldn’t have had either if he’d made a different decision in the late summer of 1965.

He had just turned 29, and he seemed to be settling into the family pattern of working for the U.S. Army. His father was well on his way to becoming a general, and the son had been commissioned as a second lieutenant and trained as a helicopter pilot. Because he had a B.A. and an M.A. in literature (the latter from England’s Oxford University), he was offered a position teaching literature at West Point. He was set for life.

He threw it all away to become a songwriter. His wife complained and his parents disowned him, but he was determined to see it through. He moved to Nashville and got a job as a janitor at Columbia Studios, where he eavesdropped on Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde sessions in 1966. If Dylan could bring literary ambition and techniques to rock’n’roll, Kristofferson asked himself, why couldn’t he do it in country music?

That’s just what he did—though it took a while for anyone to notice. When they did, it changed country music forever, opening the door for such talented writers as Townes Van Zandt, (right) Guy Clark, Steve Earle and Rodney Crowell to do the same—all Texans like Kristofferson. He showed them how to tackle formerly taboo topics with such understated realism that the songs could not be denied.

In 1966, to make some money, Kristofferson returned to helicopters. In one famous incident, he landed a copter in Johnny Cash’s backyard to hand him a song demo. The furious Cash (left) threw the cassette into a lake and chased the trespasser off his property. Four years later, Cash would have a #1 country hit with Kristofferson’s “Sunday Mornin’ Coming Down.”

Kristofferson spent much of 1966 flying copters to oil rigs off Louisiana. In his off-time, he wrote “Help Me Make It Through the Night” and “Me and Bobby McGee.” When he returned to Nashville, he had the ammo to conquer the town. The walls keeping out poetic upstarts began to crumble in 1969. Roger Miller had a #12 country hit with “Me and Bobby McGee,” and Faron Young had a #4 country hit with “Your Time’s Coming.” Johnny Cash was no longer chasing him off the lawn but was introducing him at the Newport Folk Festival.

The dam finally burst in 1970. Three different Kristofferson compositions became #1 country hits: “For the Good Times” for Ray Price, “Sunday Mornin’ Coming Down” for Cash, and “Help Me Make It Through the Night” for Sammi Smith. Jerry Lee Lewis, Waylon Jennings and Bobby Bare all had Top 10 hits with Kristofferson songs. The songwriter also released a Top 10 album himself, Kristofferson. He had the hottest pen in town.

Even more impressive than this commercial triumph was the artistic breakthrough it represented. “Sunday Mornin’ Coming Down” was not just another drinking song; it’s a song about the hangover that follows and the spiritual emptiness that compels the cycle of drunkenness and recovery. The writing is full of telling details: the narrator stills his throbbing head with “a beer for breakfast” and wears his “cleanest dirty shirt.” But the physical pain is nothing compared to the mental anguish. Stumbling down the deserted sidewalk, the tolling church bell echoes “through the canyons like the disappearing dreams of yesterday.”

The narrator of “Help Me Make It Through the Night”—a male in Kristofferson’s version, female in Smith’s—is trying to avoid such desolate loneliness by finding a stranger to sleep with. The song begins with exquisite detail: the woman pulls a ribbon from her hair, letting the tresses loose, much as she’s letting her inhibitions and scruples loose. There’s no thought of a long-term relationship—“Let the devil take tomorrow,” Smith sings—all that matters is some consolation in the present.

When the Country Music Hall of Fame published Heartaches by the Number: Country Music’s 500 Greatest Singles by David Cantwell and Bill Friskics-Warren in 2003, Smith’s version of “Help Me Make It Through the Night” was #1. It was a plausible choice, for it combined historical importance with artistic excellence. Nashville has always been skittish about unmarried sex, but here was a song that treated the topic with such naturalism and irony that it could not be resisted. Smith’s vocal was so unapologetic and yet so unboastful that it was difficult to object.

Within three years, Kristofferson released four albums: Kristofferson (reissued as Me and Bobby McGee ), The Silver Tongued Devil and I, Border Lord and Jesus Was a Capricorn. Those 42 songs included almost every song that he’s remembered for today. It was an astonishing burst of creativity, but it was a short burst. Kristofferson released seven singles from the four albums, but only two of them made the country charts: “Josie” at #70 and “Why Me” at #1. The latter was a twisted gospel song that has the narrator asking God why he has received so many blessings when he’s so undeserving. It’s a question many listeners had asked without ever hearing it embodied in a song. Even though it was Kristofferson’s greatest success as a singer, the song truly blossomed in the throats of Elvis Presley and Willie Nelson.

For as great a songwriter Kristofferson was early in his career, he was never much of a singer. He’s the obvious rebuttal to the “Dylan Fallacy,” the notion that because Bob Dylan had a mediocre voice, a good songwriter needn’t be a good singer. Dylan may have had a limited instrument, but he was a brilliant singer, a riveting dramatist with his vocals. Kristofferson also had a limited instrument, but he never developed much skill as a singer either, and that made all the difference.

Kristofferson, though, had a skill that Dylan lacked: the movie camera loved the man who wrote “Me and Bobby McGee.” The two men both appeared in Sam Peckinpah’s 1973 film, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, but Kristofferson lit up the screen in a way that Dylan didn’t. Part of it was Kristofferson’s innate good looks, but part of it too was the way his sly smile and relaxed delivery implied something seductive and dangerous. That led to roles in such box-office smashes as 1976’s A Star Is Born (alongside Barbra Streisand) and 1977’s Semi-Tough (alongside Burt Reynolds) as well as art-film favorites such as Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore in 1974 and John Sayles’ Lone Star in 1996.

Kristofferson took pains to deny that his film career undermined his efforts and results when it came to songwriting, but the evidence is pretty hard to ignore. As his acting career heated up, the literary details and subtlety in his songs were replaced by catchphrases. He did score commercial success as a duo with his second wife Rita Coolidge: three Top 25 country albums, including the #1 Full Moon in 1973, the year they were married. He had an even bigger success as a duo with Barbra Streisand on the soundtrack from A Star Is Born, a #1 pop album. But Kristofferson wrote none of the songs and was overshadowed by Streisand’s vocal abilities.

In 1980, as his marriage to Coolidge was falling apart, Kristofferson wrote and recorded his final solo album for Monument Records, his label since 1970. To the Bone was released in January of 1981, a month after the divorce was finalized, but this sometimes bitter, sometimes sad album was lacking in the imagery that made his early work so compelling, There were no ribbons shaking loose from a woman’s hair, no church bells echoing down Sunday streets.

Kristofferson wouldn’t make another solo album till 1986’s Repossessed and 1990’s Third World Warrior. Both albums reflected his newfound left-wing politics. While the sentiments were admirable, the lyrics were as unsubtle as on his divorce album.

Most of Kris Kristofferson’s late-career musical successes were connected to Willie Nelson, who had devoted an entire album, 1979’s Willie Nelson Sings Kristofferson, to his friend’s compositions, reminding how good those songs sounded when sung by a great singer. With the songwriter on backing vocals, the album went Platinum. Kristofferson and Nelson then joined Dolly Parton and Brenda Lee on 1982’s The Winning Hand, an album that featured each of the four performers singing a duet with each of the other three. It was a #4 country hit.

Nelson and Kristofferson also teamed up for Alan Rudolph’s 1984 movie Songwriter, the best of Nelson’s films. It yielded a terrific soundtrack album, Music from Songwriter, which offered two duets, five solo Nelson songs and four solo Kristofferson songs. The two pals joined Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings in a supergroup called the Highwaymen. This quartet released three charting albums between 1985 and 1995, all of them enjoyable without breaking any new ground.

“Me and Bobby McGee” remains Kristofferson’s most enduring achievement. He later admitted that Janis Joplin, his lover for a brief period, was an inspiration for the song’s heroine, the narrator’s hitchhiking buddy who was game for anything. Joplin sang the definitive version, and it became a #1 pop hit after her untimely death. Its opening lines, “Busted flat in Baton Rouge, heading for the trains, feeling nearly faded as my jeans, Bobby thumbed a diesel down just before it rained,” are a miracle of alliteration, description and mood setting.

The song begins as an ode to freedom, singing every tune they know to the rhythm of the windshield wipers. But the chorus makes the song far richer than that. It acknowledges that “freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose.” And when the narrator loses Bobby too, he realizes what a steep price that is. Maybe Kris Kristofferson didn’t enjoy a long, productive musical career like Nelson and Dylan, but he wrote a handful of songs that will endure forever. And that’s a kind of freedom that justifies giving up a comfortable career at West Point.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!