ALBUMS BY SINGER SONGWRITERS

Norman Warwick is reminded by Paste

ALBUMS BY SINGER SONGWRITERS

The singer-songwriter genre contains dozens of artists doing wonderful work—often with little recognition in a world grown ever louder and ever more aggressive.

In its most literal meaning, the phrase “singer-songwriter” can apply to any artists who sing their own compositions—be it Trent Razor or Bootsy Collins. But that’s not the way the term is used in everyday conversation. Most people use the expression to describe a more specific group of musicians: those who emphasize their original lyrics by pushing the vocal and acoustic guitar (or piano) to the front of the mix in songs that draw heavily from the Celtic-Appalachian and rural-blues traditions.

Narrowing the meaning in this way makes the term more useful, for it gives us a shorthand to distinguish one group of artists from another. That’s why we have genres; they give us fans a vocabulary for talking about different sounds and styles. It’s easy to make fun of singer-songwriters, for coffeehouses and festivals are full of performers whose earnestness is all out of proportion with the mediocrity of their work. That’s true of every genre, of course, but it’s more obvious when the poor singers have nothing but wooden boxes to hide behind. So I’d like to shine a light on some of the year’s most interesting albums from acoustic songwriters.

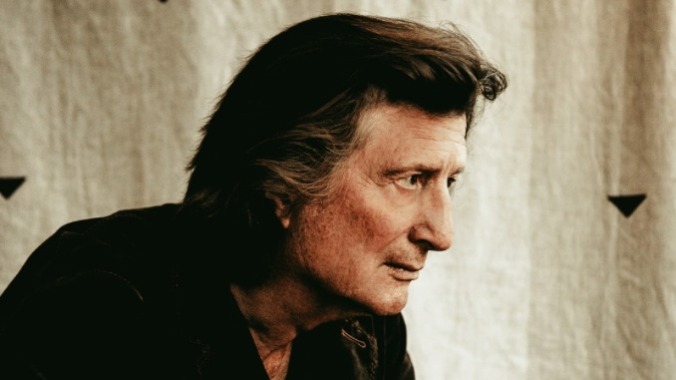

Chris Smither (left) was part of the second wave of singer-songwriters that followed Bob Dylan’s generation in the early ‘70s. Smither, now 79, became semi-famous when Bonnie Raitt covered his debut album’s lubricious uptempo blues, “Love Me Like a Man,” a song also recorded by Diana Krall. It’s still what Smither is best known for, but he has continued to develop as both a writer and performer, and his new album, All About the Bones, is merely the latest in a long string of impressive, under-the-radar recordings. Unlike most of his singer-songwriter colleagues, Smither is a terrific guitarist. When he takes a guitar solo, its slinky blues melody is an enhancement of the lyrics, not a lull between verses. And the lyrics are full of surprises themselves.

The new disc’s title track, for example, compares the function of rhythm in a song to the function of the skeleton in the body. The vocal is full of witty puns and riffs on bones, but it follows the song’s propulsive pulse to a meditation on death. The gravestone “says, ‘Here lies the body,’” Smither sings, “but body there be none. Used to be something, now it’s nothing but the bones.” This is a recurring tactic for Smither, who sings casually over his slippery acoustic-guitar licks as if just making conversation—and then, before you know it, the talk has gone deep. “Digging the Hole” begins as a joke at the expense of a fool digging his own grave, but before you know it, the singer is standing six-feet deep and the listener is right there with him. Reinforcing the downward pull of the story’s gravity is the baritone saxophone of jazz veteran Chris Cheek.

The devil makes appearances as God’s poker partner and as a Cajun fiddle maker; the narrator is waiting out his few remaining years in purgatory during the calm between storms. Harmony singer Betty Soo counterbalances Smither’s deep baritone as he hopes to make the most of the time he has left. You can say, “Carpe Diem,” but if the carp ain’t biting, he implies, you’ll go hungry.

Steve Forbert is another veteran of the ‘70s, when he had a fluke hit single with “Romeo’s Tune.” He has had an up-and-down career since then, and his new album, Daylight Savings Time, reminds us of his gift for coming up with hummable tunes and whimsical lyrics. But it also reveals his reluctance to dig deeper than whimsy and earworms. On this outing, his light, chipper tenor riffs on the boring colors of modern cars, the benefits of procrastination and walking in the woods. He’s the Jerry Seinfeld of singer-songwriters.

Ani DiFranco, a hero of the ‘90s folk-punk movement, has always been a vocal-and-acoustic-guitar singer-songwriter at heart. Sometimes it’s hard to hear that folkie core on her new album, Unprecedented Shit, but it’s there. After producing almost all her recordings herself, DiFranco invited Bon Iver producer BJ Burton to collaborate with her on this new album, and together they messed with the songwriter’s voice and guitar to create electronic textures both harsh and spacey as the songs required. The album title is an obvious reference to the pandemic and the right-wing resurgence that accompanied it. In the distortion-drenched “Virus,” DiFranco leaves a phone message for a spiky coronavirus: “I call you, Virus, but you don’t call me back, so I keep listening to my own voice.” That’s typical of her ability to tackle social dysfunction not with boring slogans but with weird angles that reveal something new.

On “Baby Roe,” the album’s first single, DiFranco addresses the child of the plaintiff in Roe vs. Wade, the daughter who was adopted when her mother was denied a legal abortion and who nonetheless grew up to be pro-choice. “Even you,” DiFranco sings, “maintain timing is everything when you’re stepping off a curb.” The electronica overlay may disorient some old fans, but the core of her art—the smart language and the punchy guitar riff—are still there.

Like DiFranco, Sam Baker is a folk singer-songwriter with a brilliant track record who has adopted techno rhythm tracks to give a new sound to his usual acoustic-guitar songs. But Baker has gone even further than Di Franco on the new album Win Win, stripping his vocals down to spoken-word monologues. This is not as radical a change as one might suppose, for the backing tracks—created by Baker and his producer Rodney Crowell—are as minimalist as Baker’s old guitar accompaniment and the monologues are not so different from his deadpan, reportorial singing on earlier records.

Moreover, the opening track “Shady Grove and the Buddha” begins with two monumental singer-guitarists: Doc Watson and Lightnin’ Hopkins. Baker’s beguiling stream-of-consciousness soliloquy eventually leads to Siddhartha Gautama, who might have become a singer-songwriter himself if he’d been born in West North Carolina or East Texas. Something similar happens when he starts talking about coyotes, rabbits, drought or jet planes, allowing his imagination to take him where it will. And sometimes, a vestigial acoustic guitar floats to the surface of the sea of looped tracks and reveals the source of it all.

When Kyshona performed at Merlefest in April, the tall, statuesque woman draped an acoustic guitar over a red-and-gold film-print wrap. The two women flanking her, singers without instruments, added strong gospel harmonies. But the South Carolina lead vocalist was functioning as a singer-songwriter: pushing her original lyrics forward with supportive but unobtrusive guitar and backing vocals. On her new album, Legacy, the arrangements are more fleshed out, but the emphasis is still on the words.

Unlike some singers coming out of the gospel tradition, Kyshona avoids the temptation to sing full-throttle most of the time. Even when she keeps her big soprano in a conversational mode, it’s impressive, and when she lets it go on a climax, the shift provides the drama that mere volume can never match. It helps that her lyrics are driven by metaphors rather than sermons. When she sings about nature, she evokes the slow, swaying majesty of “Elephants.” On “Whispers in the Wall,” she describes a home where every wall, window and floor are haunted.

Also at Merlefest this year was Adeem the Artist, who performed alone with an acoustic guitar, camo cap, red mustache and black shorts. The banter was self-indulgently meandering, but the songs were tightly constructed—and not just the witty lyrics but the hooky choruses as well. Many of the songs came from Adeem’s new album, Anniversary, recorded in Nashville with a roots-rock band and power-pop producer Butch Walker. But the songs are all built to work with just a voice and guitar.

Adeem is especially good at turning our first fumblings with sex into vivid story songs. The songwriter’s good not only with details (“her nails into my skin,” “his palm atop the small of my back,” “rub your feet and up your lеgs”) but also with keeping false sentiment out of the narrative. The singer describes being discarded after a “One Night Stand” but also doing the discarding on “Wounded Astronaut.” “Nightmare” imagines a world where fundamentalist churches are banned and gay community centers are jammed—Adeem wouldn’t approve, but it makes you think, doesn’t it? All this goes down more easily because most of the choruses invite singing along.

What are the chances that two second graders who met on a school bus in rural Maine would both grow up to be successful singer-songwriters? It happened to Slaid Cleaves and Rod Picott. The two have often co-written songs, but they have pursued solo careers—Cleaves in Austin and Picott in Nashville. Both play acoustic guitars and employ sleepy, laidback voices to sneak up on you as the lyrics’ meticulous details click into place. Cleaves released the splendid Together Through the Dark last year, and Picott has released the just-as-good Starlight Tour this year.

The first words Picott sings on the album are, “Two old dogs sleeping on a Goodwill sofa. One wears plaid on plaid; you couldn’t wake him with a Louisville Slugger.” Few songs snap into focus as immediately as that. Like that dog, the song’s narrator is tired by “that long parade of years.” On “A Puncher’s Chance,” the narrator is a veteran boxer who admits, “I’ve been caught with life’s hard left; it rattled my cage, but strength is the last thing you lose with age.” Nashville producer Neilson Hubbard adds just enough drums and steel to nudge things along. What emerges is a portrait gallery of Americans at the margins, where sheer cussedness keeps them betting against the long odds of this world: a Viet vet walking the Florida beach alone, a broke-ass Alabama farmer with a gambling habit, a Georgia oxy dealer, and a homecoming queen nursing her memories with a “Jack and Coke.” Picott doesn’t give them fake happy endings, but he gives them the dignity of three dimensions, and that’s enough.

A female counterpart to Picott’s record is Heather Little’s By Now. The first single is “Hands like Mine,” a story about a first husband who “promised me the moon, but all he had was the dark where it belonged.” In a soprano as weary as the wheezing accordion behind it, she doesn’t really blame him, “’cause they haven’t made a ring for hands like mine.” It’s one of two songs with harmonies by Patty Griffin, but Little more than holds her own with her more famous vocal partner. Little is best known for co-writing “Gunpowder & Lead” with Miranda Lambert, who turned it into a top-10 country single. On this album, Little returns the song to its voice-and-acoustic-guitar roots, proving that the lyrics are explosive enough without drums and amps. These stories take place in old wooden houses down South, where the roofs leak and the windows rattle with memories that she refuses to turn into regrets. Like Smither, Little uses “Bones” as a metaphor for a past that can’t be buried until one has danced with it.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!