OH, COME ON EILEEN

Norman Warwick introduced her with AN

OH, COME ON EILEEN (EARNSHAW)

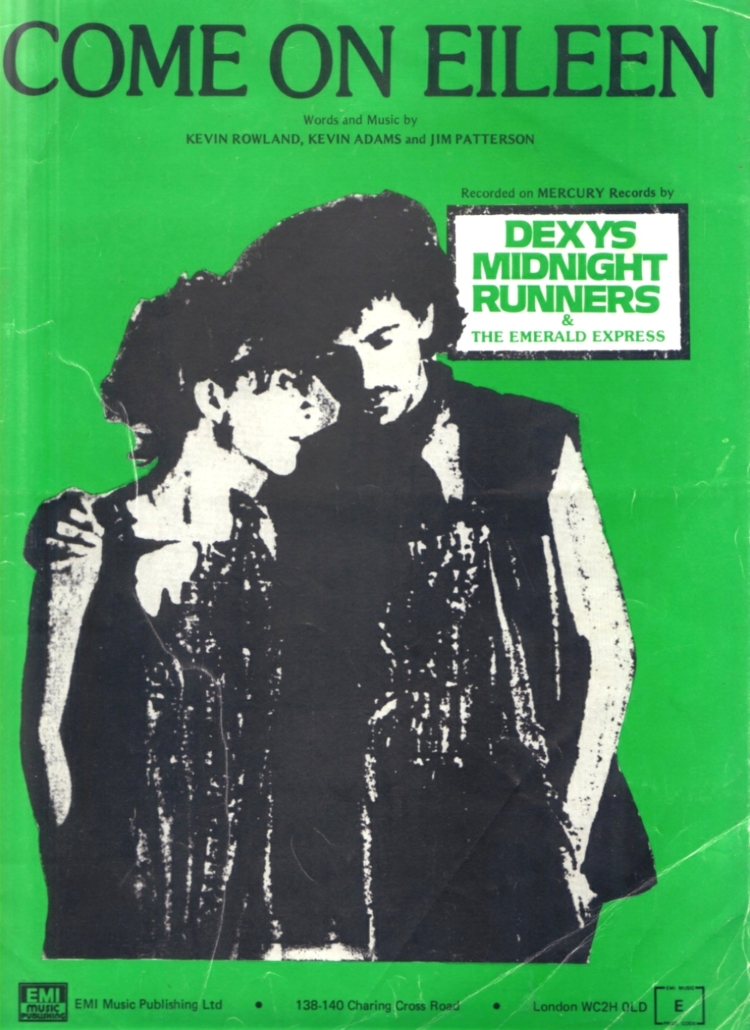

Inspired by Dexy´s Midnight Runners

Picture yourself standing in the unemployment office. Times in the nineties had become tougher than my baby boomer generation might have expected and even the stars of very recent op charts were queuing in the unemployment offices around the UK.

There’s a line, because of course there is. And as you stand there, waiting and waiting, you see some random guy looking at you. You don’t know him, but he knows you.

And then, retrieving a tune less than a decade old from his memory bank, he starts singing, expecting you to join in, “Come on, Eileen. Oh, I swear…”

You are Kevin Rowland and in the early ’90s, this is your actual life.

“Come On Eileen” was indeed inescapable for a time on its way to numerous “Hey! Remember the ’80s?” compilations and homemade mixtapes. It topped the U.S. charts in late April 1983, spending one week at the top in between Michael Jackson’s hits “Billie Jean” and “Beat It.” It was the No. 1 single for all of 1982 in the UK, where it spent four weeks at the top.

The album that spawned it — Too-Rye-Ay — has just turned forty, There’s more to it musically than just that one hit. There’s also more behind the scenes drama to it, not as widely known at the time.

I remember the song for several reasons. At the time of its release as a single it seemed to defy the timbre of the UK pop charts of the era. There was a wonderful folk/country feel to the top of the pops performances delivered by the band with their violins, hand claps and soaring chorus. It was a feel good record and the band´s vocalist and leader was one of the most charismatic performers of his time.

I also remember the song because some time in the final decade of the twentieth century. I made friends with a fellow poet in my area and we would often bump into each other at slams or readings, or in the library which, like a dozen or so of Rochdale´s literati, we considered to be our office and, often, our stage.

Eileen Earnshaw (right) was a mentor to many of us and was not only a great writer of some profound poetry but also worked tirelessly to perpetuate the legacy of Rochdale´s role in creating the co-operative movement. She still has a way of making arcane history interesting and relevant and still runs Riverside Writers, facilitating a creative writing group in Rochdale.

I don´t know if Eileen actually knew of Jack Lee who with his wife and daughter was the resident musical host at The Fisherman´s Inn beside Hollingworth Lake, but Eileen and Jack shared certain traits in their performance. Jack´s family band was known, by name and performance, as Haphazard. Jack would forget the name of a song as he introduced it, stumble over words and invent a new chorus half way through a song he´d been singing for forty years, could take forever tuning up and deliver rambling introductions that were longer than the song they introduced. He had an aw, shucks, grandpappy attitude that matched his silver haired, silver bearded appearance, but my God, the Haphazard performances of My Dixie Darlings was demanded by the audience at every gig, and has stayed with me forever.

It was twenty years later that I met Eileen and fell in love with her poetry, that like Jack Lee´s music was presented in a somewhat shambolic manner. Carrying her poetry to the microphone she would invariably drop some of the loose leaf pages she was carrying, bend down and collect them up only to find they were now in the wrong order and that her first poem was tucked away somewhere in the middle of twenty odd pages, (only three of which she intended reading !)

Her introductions were of the ´this is a poem I wrote, oh I can´t remember when, and to honest I´m not sure what it´s about or why I wrote it, but see what you think,…oh hell, where´s it gone?´

We loved her for this because we were prepared to forgive her anything for the wisdom of her words, the perfection of her poetry and for always leaving thoughts in our heads and hearts that would stay with us forever.

There was a period of a few years when Robin Parker, another Rochdale poet, and I were hosting the Bard From The Baum Sunday night poetry readings. Eileen, along with other local poets like Michael Higgins, Catherine Coward, Val Chapman and Seamus Kelly lent an elevated air to our events. However, as hosts, Robin and I knew we had to run the events to time. After an even lengthier preamble than usual I chivvied her up with a ´come on, Eileen´ and Robin immediately followed with an oh come on Eileen in the style of the Dexy´s hit of twenty years previously. Suddenly the whole room burst into the Too Rye Ay chant and the hand-clapped chorus of increasing urgency.

The legend was lite. From that night forward Eileen was always given that accompaniment as she walked slowly to the stage and gathered her thoughts.

In writing that precursor to the song we are about to discuss, it has suddenly dawned on me how clever Jack Lee and Eileen Earnshaw were being. They were like Les Dawson, playing the piano very badly but absolutely brilliantly. Or they were emulating Tommy Cooper putting the rabbit down the wrong hole but brilliantly always pulling it out of the right hat.

However, we have now reached the beginning of this article, so let’s start with this corrective. Dexy´s Midnight Runners were not a one-hit wonder, at least not in the UK. Their debut album — 1980’s Searching for the Young Soul Rebels — reached No. 6 in the charts there with lead single “Geno” reaching No. 1 and follow-up “There, There, My Dear” also reaching the top ten. Both hits were co-written by lead singer Kevin Rowland (lyrics) and guitarist Kevin Archer (music).

Things should have been fine for the second album, right?

Nope. Rowland had a tendency towards lording over every detail. Smarting from some criticism by music journalists of the debut, he imposed a press embargo. According to Archer, he needed to be called “Al” because somehow Rowland didn’t want two Kevins in the band anymore.

Rowland’s manner of dealing with things chased off most of the band. He told the Guardian in 2014, “I take responsibility. I was far too controlling and aggressive. One day, five band members announced they wanted to go their own way, as Dexys, and get a different singer. At first I was relieved. All that stress just went. Then after a couple of days I thought: ‘F*** that! It’s my band name!’ and started to get another band together around myself, Jim, and Kevin Archer. Then Kevin left, too, because he was disillusioned.”

The Dexys of 1980 was effectively now three bands, with Rowland and trombonist Big Jim Paterson remaining in the original band. Five members — bassist Pete Williams, saxophonists Geoff Blythe and Steve Spooner, drummer Andy “Stoker” Growcott and keyboardist Mick Talbot – formed the Bureau. Then there were the Blue Ox Babes, led by Archer and also including former Dexy´s keyboardist Andy Leek

The latter began working on demos, expanding on the sound of Searching. “I liked T.Rex but was also listening to a lot of western swing, and North American black music, spiritual and uplifting,” Archer told Record Collector in 2009.

“We listened to The Chieftains and Van Morrison and I got some Arabic music, where the violin sounded weird. We found some gypsy Romany music and Archer started listening to cajun. He used instruments such as the Jew’s harp, melodica, mouth organs and, of course, the fiddle,” Yasmin Saleh, who was a Blue Ox Babes member and Archer’s girlfriend .

Rowland and remaining band member Jim Paterson started writing new songs, releasing three singles in 1981.

The demo process for Blue Ox Babes, meanwhile, was going well. There was some confidence, but Archer sought the opinion of his former band-mate Rowland. “I’d had a great time recording the songs. It was a breeze,” he told Record Collector. Everybody said, ‘They’re good.’ But I needed to get another opinion. Rowland was my old song-writing partner so no harm, eh? I took a Walkman over to his house. And he said, ‘I can’t hear it that well, can I borrow the tape?’ Then I never heard from him for about a year and, one day, I was in my flat with the group. I happened to switch on the radio and ‘Come On Eileen ‘was on. I thought, ‘We’ve had it now.’ I felt gutted. They’d adopted a similar style to us.“

It was a body blow to Archer’s confidence that not even an offered record deal from Stiff could fix. The Blue Ox Babes would finally release a trio of singles in 1988, but the planned album was shelved, where it would stay until 2009 when Cherry Red released Apples & Oranges, which collected the singles and unreleased material.

The Bureau, meanwhile, released a self-titled album (called Only In Sheep in Australia) and were disbanded by the time Too-Rye-Ay was released. Talbot would go on to have success as a founding member of The Style Council. Blythe would join the TKO Horns, which included Paterson, who’d left Dexys during the recording of Too-Rye-Ay. The horn section would play with the likes of Elvis Costello, among others.

The history of Dexys, its line-ups and the other projects its members have taken part in (and the artists they’ve played with) could, if plotted out, start to resemble the Pepe Silvia meme from It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia.

Rowland’s views of what happened have shifted. He said in 1993, “After Searching For The Young Soul Rebels, when (Archer) left, we were both experimenting with strings. I wasn’t getting what I wanted: he found it and I stole it. As a result, he disbanded his group. Dexys had taken his sound and succeeded with it.”

Years later, he told the Guardian, “Around 19 years ago I gave an interview about how I’d stolen ‘Come On Eileen’ from Kevin Archer. Some of it was true. Most of it was me punishing myself. I was in a dark place and thought it had all been him and I had no talent. What actually happened was … he played me his demos and he was using a combination of a Tamla-style beat with violins, which I thought sounded better than what we were doing. So I nicked that style, and the idea of speeding up and slowing down. I didn’t steal one note, one chord, one melody.”

Rowland, starting in the ’90s, did sign over half the royalties for Too-Rye-Ay to Archer, a percentage substantially reduced some years later.

The other addition from the Blue Ox Babes demos was one of the players, as violinist Helen Bevington (soon to be rechristened as Helen O’Hara to sound more Irish — Rowland’s idea) stood out to him. He’d originally wanted to have the horn players play strings as well before deciding to add strings separately.

The horn players, who would be brought back to finish the sessions as hired hands, left due to a combination of reasons, including artistic ego, perhaps a bit of booze and, in Paterson’s case, a desire to spend time with his new girlfriend Sandra. The latter reason more than paid off as they’re still together, having married a few years later.

The album came out and everything appeared set, but then the first single, jaunty album opener “The Celtic Soul Brothers (More, Please, Thank You)” failed to crack the UK Top 40. “Come on Eileen ” appeared destined to meet the same fate, if not for one BBC Radio 1 DJ — David “Kid” Jensen who’d kept playing the song. It finally gained momentum which, boosted by a Top of the Pops appearance, vaulted the song up the charts. Buoyed by its video getting all over MTV, similar success followed here.

While Dexys would be one-hit wonders here, they kept going a bit longer on their home turf when the third single, a bouncy cover of Van Morrison’s “Jackie Wilson Said (I’m In Heaven When You Smile)”, a classic from the years before Morrison became the living embodiment of The Simpsons’ “Old Man Yells at Cloud” gag.

As it turned out, Dexys had created a solid album, rather than a few singles surrounded by filler. Rowland might have found inspiration in what the Blue Ox Babes were working on, but it’s clear in retrospect that Too-Rye-Ay wasn’t exactly a 180-degree turn from Searching for the Young Soul Rebels.

Rowland’s loose, yowling yelping voice was the same. The old soul influence was still there. The Celtic folk influence, complete with the addition of the strings, was the change that pushed them over.

And it should be noted that Rowand’s desire to add strings predated anyone else’s demos, a desire that led to some of the departures.

Too-Rye-Ay isn’t all uptempo party. The empathetic waltz of “Old” contrasts with the bitter anger of ballad “Liars A to E”. Meanwhile, the bittersweet “All and All (This One Last Wild Waltz)” slows things down further with a relationship with an authority figure winding down.

“The Celtic Soul Brothers”, lyrically by Rowland about himself and Paterson (as well as the band as a whole) might have enjoyed a better fate had it not been the leadoff single. Someone else thought so, as it got a re-release in the spring of 1983 and reached No. 20.

“Let’s Make This Precious”, with its bright horns and break with handclaps, carries over some of Searching’s vibes, albeit with violins. The bounciness of “I’ll Show You” belies its lyrics about how the line of emotionally abusive adult behavior towards children connects to problems in adulthood.

The team Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley, fresh off working on albums from Madness and The Teardrop Explodes and soon to produce Elvis Costello and the Attractions, produced the album with Rowland. The duo took the lead (more on that in a bit) and put together a polished, but not slick, catching the vibe of a soulful band on a good night.

Take “Plan B”, a reworked version of a 1981 single, adding a quiet intro before bursting into brightness with a fuller-sounding version than the original.

It’s clear Rowland is a fan of his influences, even if he doesn’t quite sing like them. His voice is an acquired taste at times,with the falsettos and various overwrought mannerisms threatening to go over-the-top at times. Still, he has an undeniable charisma and the band itself is a good support structure, tight enough to keep him tethered and loose enough to let him play.

Even with all that it can be said about the rest of the album, “Come On Eileen” is Too-Rye-Ay’s highlight, with its deft key changes and utterly undeniable chorus that will stick in the brain whether you want it to or not.

The song was originally about some of Rowland’s favourite singers — the chorus of “James, Stan and Me” with Stan being an inside joke name for Van Morrison. “We’d been outside the Birmingham Odeon in ’78 and it said ‘Van Morrison’ in lights and some girl said: ‘Oo is he? Never ’eard of him.’ We went: ‘Oh it’s Stan Morrison. He’s a comedian, they spelt it wrong,’” Rowland told the Guardian.

Even with Morrison’s correct name, the song wouldn’t last long in that incarnation, as Rowland reworked the lyrics to turn it into a tale of repressed Catholic teenage wooing, with Eileen being a composite of girls he knew in his younger years.

For a song about teen sex, there’s an innocence to it (he says “please”), a sort of Celtic “Go All the Way”, or perhaps a less creepy “Only the Good Die Young”.

And it all comes in a package where not only the chorus sticks, but there’s also the part three-quarters of the way through designed for audience singalongs (“Come on, Eileen, ta-loo-rye-aye”). If the new wavy synths of the period were more influential, the folk-inflected soul of it is still pure ’80s pop joy.

Even though Too-Rye-Ay would be the biggest hit in Dexys career, Rowland had his misgivings with its production, something he didn’t feel he had the way to express while recording. Even though he appreciates the Langer/Winstanley team, he felt the finished product was too poppy.

“I knew it was great to have the success that album had. At the same time, I felt it was a shame,” he told Classic Pop earlier this year. “I felt a bit fraudulent promoting Too-Rye-Ay, because I knew straight away it wasn’t right. The best you can hope for when you finish an album is that it sounds as good as you can possibly get it at that moment. You feel right when you leave the studio, because you can’t get it any better.”

Rowland’s response to Too-Rye-Ay’s success was to not even attempt repeating it. At one point, the legendary Tom Dowd (whose credits included the likes of Aretha, Ray Charles, Coltrane, Rod Stewart, the Allman Brothers) was the producer, but those results were shelved.

Gone was the Celtic vagabond image, as the band, winnowed down to a quartet, appeared in yuppified businesswear on the cover of 1985’s Don’t Stand Me Down. Rowland, after a lengthy, over budget recording process was not only refusing to do press again, he was refusing to let the label release a single.

Don’t Stand Me Down flopped. While time has definitely been kinder to Rowland’s artistic ambitions, its commercial failure led to the band’s breakup.

“I’d been too confident, too arrogant. I thought everyone would hear our new music and go: ‘Wow,’” Rowland said.

He’d increasingly turn to drugs (particularly cocaine), eventually going to rehab, as well as needing public assistance for a time when the money ran out.

Rowland’s loose, yowling yelping voice was the same. The old soul influence was still there. The Celtic folk influence, complete with the addition of the strings, was the change that pushed them over.

And it should be noted that Rowland’s desire to add strings predated anyone else’s demos, a desire that led to some of the departures.

And Rowland (second left in picture right), now long sober, even found a way to enjoy his most successful creation, which has been a mainstay for DJs at events like wedding receptions. Many years after that low point in the unemployment line, he was in better surroundings in Brighton. As he told Classic Pop, “I’d just started dating a woman who worked at American Express, who were having their works do at a hotel on the seafront. Nobody knew I was there and… I didn’t really dance, but I watched everyone else dance to it and that was good.”

Four decades later, the album that spawned it still is.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!