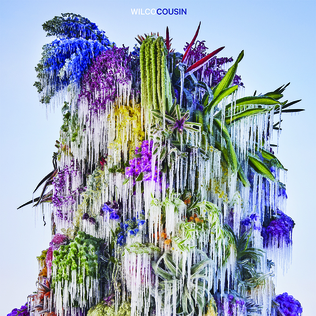

LONG LOST COUSIN WILCO

Norman Warwick hears of a

LONG LOST COUSIN WILCO

“Depending on how you look at it, the connection to The Bear was an unfortunate—or fortunate—coincidence,” singer-writer Jeff Tweedy (left) recently told Paste on line magazine, laughing, during a Zoom from Wilco’s Chicago studio, The Loft.

“It was certainly not conscious. I saw most of the first season and I hadn’t seen any of the second season. And then people started saying [we titled it after the show], once we announced the record. I don’t really remember it being that prominent in the first season, that ‘cousin’ thing.”

The title Cousin wasn’t even the first choice for the record. Initially, Wilco wanted to call it Infinite Surprise, after the opening track. But with a limitless action like “infinite,” you open yourself up to a lot of speculation and a lot of expectations, so the band pivoted to something simpler—something that couldn’t become oversaturated with destiny or assumptions. “[Cousin], I think, internally, it was a reaction to the working title—feeling over time like it was a little too heavily weighted,” Tweedy explains. “But it just felt like that was too leading to somebody’s anticipation of what the record might be. Are they going to think that they’re going to be surprised every 10 seconds? It’s just a more weighted, meaningful phrase than just the word ‘cousin.’”

“I’m cousin to the world,” Tweedy confessed upon the lead-up to the record’s release. While the intentionality behind the title isn’t tethered to The Bear, the meaning of it rings in similarly. In the show, characters refer to each other with such an affection, even if they aren’t blood-related. It’s a gesture of communion, of brotherhood, of understanding. “I’m here and you’re here. We’ll get through this one way or another.” That’s Cousin. That’s Wilco. “I think I was, primarily, looking for a word that could absorb anybody’s interpretation of the record,” Tweedy adds. “Sometimes you just want a word that’s hollowed out and neutral and just has a nice sound to it. That was what the appeal was, that Cousin could come to mean this record to somebody—the way a band name stops meaning the words, like the Rolling Stones. Over time, it just absorbs the impression that your work has made.”

Tweedy did see “Review,” the seventh episode of season one, where a 12-minute live rendition (from a 2005 show at the Vic Theater in Chicago, which would appear on the record Kicking Television) of “Spiders (Kidsmoke)” soundtracks almost the entire story—which is also a bottle episode, and maybe the most anxiety riddled attempt in recent memory. Tweedy calls the song cue an “inspired music programming choice,” noting that it’s rare to see such long sync licenses. But, like the rest of us, his reaction to the unraveling of the episode and the well-being of the show’s characters is one of communal frustration.

“I think I had the impression most people would want, that maybe things would settle down if you turn that off,” he says, laughing. “Maybe it’s not helping if that’s in the background. Usually, when I hear stuff in movies, or out in public, if it’s being played over the PA in a restaurant or something, it takes me a long time to realize that it’s me. [Watching The Bear], I was sitting there thinking ‘This is really familiar,’ because, especially something like that, that’s a live version that I’ve probably when the songs and sounds of Cousin started coming together around the time Wilco put out their 11th album, Ode to Joy, in 2019. An encounter with Cate Le Bon at the band’s perennial Solid Sound festival (at MASS MoCA in North Adams, Massachusetts) spurred the work in motion, too. Over time, the architectural skeleton of Cousin slowly began straightening out. But, in the four years in-between meeting Le Bon and releasing Cousin (right), Wilco would pivot from that work and churn out 21 songs for Cruel Country in 2022. This era of productivity for the sextet is greatly a product of Tweedy’s own output, given how prolific he is with his writing (three books, three Wilco albums and three solo albums in a five-year period solidify that truth alone). Making Cruel Country was a breath of fresh air for the band—not because making Cousin was an exhausting labor, but because these 10 tunes required extra care and extra attention. To let songs that are this conceptually and constructionally dense and rewarding become what we hear them as on the record, getting to that destination can be intense and, sometimes, you just gotta cut through that intensity with some lower-stakes noise hardly ever listened to—so it’s like, ‘This sounds like something I should know.’”

“I write a lot of songs, so I always feel a little anxious to get them out into the world—because I feel like there’s no way I’m ever going to be able to share all of them,” Tweedy says. “And I write them because I like sharing them. What Cruel Country did was buy a little time to give these songs [from Cousin]—that really seem to be crying out for this kind of treatment—a little bit more time for that to actually happen, a little bit more time to reach their potential. You can’t really rush that type of arranging or sonic shaping. It’s a more considered process. The song shapes on Cruel Country were really easy to grab a hold of, and everybody really responded to them quickly.”

A big part of Cruel Country was that it was a band-in-a-room record, the first one Wilco had made in at least a decade. And, even though there was overlap between that record and Cousin, the latter didn’t sport the same intimacy. A song like “Sunlight Ends”—which sports this real strange and cosmic instrumentation of bubbly, almost robotic guitars, Kotche’s rototom cues and ripples of electronica—is nearly impossible to lay down with six guys all chipping in at once. “It’s almost like you have to get the skeleton together and then bring in somebody to do the eyes,” Tweedy notes. “It’s more fragmented as a process than just getting together in a room and playing. It’s almost like you have to write the score and you have to show everybody a little bit of the shape, so that we can all see the same thing at the same time. Whereas, if you have a song that’s three chords and built on a country shape, everybody goes, ‘Oh, I know what to do with that.’ And then we all work within our personal preferences on how we bring ourselves to that and make it our own.”

Le Bon would stop by The Loft in late 2019 and record a cover of “Company in My Back” from A Ghost Is Born for Uncut and then, in 2022, she was invited to produce Cousin. The line between her work and Wilco’s is not blurred; her last solo LP, Pompeii, features a striking minimalism rife with complex intimacies and divine poetics that are not unlike the interpersonal and graceful portraits Tweedy lines his records with—and, especially on a record like Schmilco, where the band leaned into delicacy and soft spots with more intent than ever before. The best American band and the most underrated producer in music—it’s a collaboration that makes sense, and it lends a chromatic touch to Wilco. And, via Le Bon’s guidance, a big part of her presence on Cousin was using subtle, minor detail changes to completely reroute the destinies of songs like “Ten Dead” and “Soldier Child” and “Meant To Be.”

It’s exciting to be around Cate, it’s exciting to work with Cate,” Tweedy says. “We had just done Cruel Country, and that was such an easygoing and fun process. I think, initially, there was a little tension as to how this is going to work, because [Cousin] wasn’t going to be easy like that. It wasn’t going to just be an immediately rewarding scenario. It was going to take some time and some trial-and-error and some frustrations. But, Wilco is a band that, once we understand the parameters of what it is we’re searching for, everybody’s on board. I spent the bulk of the time working with [Cate] within the band, and it became very clear very early that this wasn’t going to be just be six guys in a room playing with Cate sitting in the room and directing everybody. It was gonna take more individual exploration.”

Wilco just isn’t a band that’s going to phone it in. As a longtime fan, you begin to see how divided their audience can get. There’s the old heads, the Being There through A Ghost is Born purists who don’t completely engage with the contemporary stuff; then there’s the new guard, the folks who devour the dBpm-era work. But there’s a reason why Yankee Hotel Foxtrot wasn’t even in the same stratosphere of attitude or sonics as A.M.: Wilco refuses to settle into one mode, instead pointing their aim at a lifetime of surprise. And, across 29 years together as a band, they’ve fully committed to the idea that the only type of music worth putting out is the music they haven’t made yet.

I’m afforded a great luxury of having some really great musicians trust me and believe in me enough to get uncomfortable,” Tweedy says. “It doesn’t seem like bands really want that over time, I think they work towards some way to make it easier or more comfortable. We’ve never made any of the records we’ve made the same way twice, and that’s a built-in kind of discomfort. And, a lot of people maybe don’t even hear it because, once you’re a band for a long time, you’re also competing with everything you’ve ever done. And there’s just a lot of baggage; you’re never going to be a band nobody’s ever heard of again. And we all understand that. The only way to combat that kind of familiarity being diminishing—being projected onto us—is to allow ourselves to be uncomfortable and accept it as being a challenge, to live up to our own idea of ourselves.”

In his memoir, Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back), Tweedy wrote that melody is king. On those Y2K Wilco records, like Yankee Hotel Foxtrot and A Ghost is Born, the orthodoxy of pop melodies were obliterated—and the band has done that again on Cousin—though Tweedy acknowledges the spectrum of music he cut his teeth on. In his new book World Within a Song, he lends space to everything from R.E.M.’s “Radio Free Europe” to Billie Eilish’s “i love you” to Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You” and cites them all as integral fixtures of his musical identity, down to a molecular level. There’s a moment on Cousin closer “Meant To Be” where Tweedy’s vocals go to pockets of pitch that are underscored in his oeuvre, and that experimentation comes from a desire to not see himself as just one thing or one kind of musician.

“I admire and wish—a lot of times—that I had been more disciplined in my aesthetics in my life and had been able to plow a very narrow path for myself. But, I’ve never had a coherent philosophy about music, so I’ve always wanted to be everything. I’ve always wanted to hear myself be able to do everything. And that allows a lot of things to grow based on ‘Well, I’ve never sounded like Echo & The Bunnymen before.’ I’ve never tried to write a song like Echo & The Bunnymen or The Cure. There’s a realization that that music is actually a part of my vocabulary as much as any country music—maybe even more. Maybe that’s not apparent to a lot of people, but I grew up in that and in the heyday of that kind of pop music. It’s, maybe, almost more like giving myself permission to explore that type of song. I don’t think it ends up sounding like New Order or anything like that. It sounds like Wilco.”

Tweedy’s songwriting is glacial and organic. When he was writing his memoir, he was also working on his solo records Warm, Warmer and Love Is King and, as a result, he began making songs that were much more direct and biographical—because his focus was so centered on memory and on prose. That period of a few years really gave him, and Wilco, time to remain in a pseudo-abstract energy. Tweedy’s aim on projects like Ode to Joy and Cousin is to make his language conjure the mysticism of negative spaces—to not say anything but still rein in imagery somehow, tapping into disciplines (like haiku writing) where the words aren’t necessarily related but can extract consciousness and perceptions through description. “It’s like writing the songs and then getting out an eraser and taking away some of the specifics,” Tweedy adds. “There’s a lot less lyrics on [Cousin]. There’s, I think, a real effort to try and stay in some economy of language and let the sonic textures of the record be more communicative.”

The first time I ever heard a Wilco (left) song was in late 2014, when I was 16 and getting my film buff hat sized for the first time. I was making it my mission to watch all of the critical darlings of the year: Whiplash, Birdman, Gone Girl, Inherent Vice. At some point, I got around to seeing Richard Linklater’s Boyhood. There’s a scene around the halfway point, where Ethan Hawke’s character is driving his Pontiac GTO and absolutely crooning to Wilco’s “Hate It Here.” I was entranced without a hitch and, immediately, went to my Beats Music app (before it was bought up by Apple Inc. and turned into Apple Music in 2015) and added every song from Sky Blue Sky into my library. I consumed Wilco’s catalog like it was my well-kept secret; no one around me was kicking it with Yankee Hotel Foxtrot like I was, though I certainly tried to get everyone hip. It wasn’t until about five years later, when I was visiting my dear friend in Los Angeles on college break, that I saw he had an Uncle Tupelo CD in his car. It’s the little things.

But this is just to say: When you spend enough of your life listening to one artist, they become such an integral piece of you. I remember the exact second I heard Wilco for the first time because it follows me on a molecular level. I see a lot of similarities between Sky Blue Sky and Cousin, if only because they both tap into a place of recovery, a present-tense circumstance of reconvening with loved ones and reshaping existing relationships after separation or distance. In between A Ghost is Born and Sky Blue Sky, Tweedy had entered a rehabilitation clinic program to receive treatment for his ongoing addiction to painkillers. He wrote in Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back) that, when Wilco was making Sky Blue Sky, he was making an effort to forego the myths that surround suffering and art. Cousin, I think, is rid of myth altogether—in that much of the struggle and survival across the album arrives as if from a place of plainspoken truth towards a reality that’s unavoidable.

Lyrics like “it never hurts to cry, the dead awake in waves” or “I’ve always been afraid to sing, somehow that’s all I do, strange as it seems, I’ve outlived my dreams” feel existential yet grounded, pulling at this fabric of disquiet. Yet, moments like “holding our hearts close together, keeping to ourselves an empty sea, so we can believe our love is meant to be” or “you dance like the dust in the light where the sun comes in, and I’m following” or “let you save me, save me again” employ nebulas of grace and affirmation. Despite the conceptual nature of a record like Cousin, there’s a real focus that lives beyond the pushes and pulls of reality and clutter of chaos. That attention lives in the dichotomy of love and distance. It’s a complex braid to untangle, but one that always, always, always reveals the stunning branches of empathy that ache beneath the surface of Wilco’s offerings.

“Being a person in recovery almost 20 years, one of the things that you think—when you’ve been through recovery, or you’ve been through treatment for mental health issues—is there’s a sense of gratitude that you’ve been given this hurdle, something to give your life some meaning, in a negative way or in a positive way. It’s something that not everybody has and, being forced to look at yourself honestly, being forced to introspect on a daily basis to keep yourself healthy, leads to a lot of matter-of-fact wisdom. It’s not really that fucking hard. On one level, it’s really very simple. On another level, I’m saying the stupidest shit in the world but it’s, for some reason, very complex and hard for humans to keep an eye on an authentic self. I would easily be compelled to do drugs again if I wasn’t centered and really focused on the things that matter and things that are my problems that I can distinguish from other peoples’ problems. It’s a good thing to have happened to you, in a weird way.”

Sky Blue Sky wasn’t given much of a fair shake upon its release in May 2007. “I think they’ve all been given an unfair shake,” Tweedy chimes in, cracking up. Folks wanted another Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, but even A Ghost is Born suggested that wading through the same water was never going to be on the band’s radar. Tweedy chalks the initial response to Sky Blue Sky coming out at “the height of gatekeeping” and points to Wilco not getting the benefit of the doubt that there was a conscious decision to make a straightforward record using some of the vocabulary of soft rock and multi-generational motifs and textures. “I was making the first record I’d made since I had been in the hospital, and I really didn’t want to make a lot of decisions,” he says. “I wanted everything to be us sitting together and making arrangements together. The thing that’s quite puzzling to me is that [Sky Blue Sky] is looked at as very simple. But it’s not, it’s actually very hard to play a lot of those songs. The arrangements were really highly considered.”

Every record Wilco makes is met with warmth from fans and admirers alike, even the projects that folks might not fully get until the next one comes out. I felt that way about Star Wars and Schmilco (two back-to-back releases that were originally intended to be one double album), in that I truly didn’t appreciate the former until I got heavily obsessed with the latter. And then, just when I expected Ode to Joy to be this continuation of diaristic, softened folk songs about childhood and history, Tweedy and the guys made a percussion-forward, troubadour joint about the world’s decline and the act of embracing our loved ones. To spend a part of your life with Wilco’s music is to give yourself the gift of holding stock in a band that’s unafraid of taking a left turn away from what’s expected of them. “I think that people have a lot to choose from in Wilco and, wherever they end up coming into the band, they might want more of that the next time around, because they made a connection with us through this certain thing,” Tweedy adds. “And the next thing is usually not that, so there’s a reaction to that—and, maybe, even a repulsion.”

On Cousin, the record begins with white noise—as if you’re listening to the noise pollution outside an apartment window. It’s as if Wilco have embedded the majesty of Chicago and of metropolitan wonder and the places the band has called home into the actual DNA of the band and the songs they make. And Chicago, it’s filled with monolithic shapes and beautiful, ornate architecture, and there’s so much sonic information. You aren’t just walking through silence, with every step you become an attachment to that busyness. “The beginning of ‘Infinite Surprise,’ to me, I like the record starting as if you were just being dropped into something that was already happening,” Tweedy explains. “Like, when you come out of a movie theater and the wash of street noise hits you for the first time—which is what happens every day when I leave the studio. I walk into the world as it’s already happening, and that’s an exciting moment. That’s an exciting feeling.”

Even though parts of Cousin were already being worked on before Cruel Country was written and recorded, they make sense in a sonic order of continuity—as if Tweedy is leaving a room with his band and exiting into this panorama of commotion. That cohesion anthologizes the Wilco canon like a short story, or an assembly of pointed, divorced vignettes embossed with a network of subtle throughlines. There’s an effort there, to—as every record or, even, every side of a record, ends—pick up the conversation where the band left off, but in a different room.

Cousin is the most industrial record Wilco has made since starting their own record label, dBpm, in 2011. What I mean by that is there’s a lot of computerized elements, heavy overdubs, samplers and pitched percussion on this thing—be it the startling, melancholic drum machine on “Sunlight Ends” or the jagged soundscape swell on “Pittsburgh.” Having gone from making a full-blown Americana, singer/songwriter statement like Cruel Country to fashioning a bold, diverse and complex palette on Cousin in just a year’s time, the traditions of “fan service” are fully out the window. Instead, Wilco put a lot of investment in giving their listeners something worth disentangling and being curious about—and much of the reason for these changes in speed and creative challenges across albums is a result of Tweedy wanting to be heard and wanting to reach people.

“I have a really sincere desire for there to be a connection and to communicate,” he says. “In my mind, one of the elements that you have to use in communication is surprise. It’s one of the elements of poetry, it’s one of the elements of art. If everything unfolds in the way that you expect it to unfold, you tune out. You become very bored. I become bored—as a listener, as a reader—if I’m not having the rug pulled out from me from time to time. I think it’s just better that way. I think art is better that way, to have to trust that you’re going to come to your audience in a way that treats them with respect—like they’re going to be willing to invest in it, you assume that there’s a desire. That’s a leap of faith. And, then, there’s a leap of faith in us that, when we pull the rug out, we’re not just doing it just to pull the rug out; we’re doing it so that you can see the song again. You have to fuck with the language, you have to fuck with the status of how people perceive things to be heard again, to be understood again. And it’s just the only way it works, to me.”

The song “Soldier Child” is the most Wilco-sounding part of Cousin. There’s an outro guitar part—which Tweedy played himself, and nailed on the first take—that reminds me of the pedal steel on the Cruel Country track “Tired of Taking It Out On You,” at least in the sense of what emotional response I pulled from it. I’m not a musician, but I hear these fragments in songs and they yank something from my soul. Wilco have made it a habit of continuing the stories in their songs through instrumentation, be it by constructing a lick or a piano sequence as if they’re characters in the songs. Tweedy calls it “a wordless feeling that continues the thought or the emotion. It’s something that you do for 30 or 40 years, you have a guitar in your hands so much in my life that, at some point, miraculously, you—if you want it—become more conversant with it,” he says. “That started happening for me around A Ghost is Born, when I was forced to play all of the electric guitar just by the situation of the environment and the band changes. I looked around and it was like, ‘Oh, if I want a lot of guitar on this record I guess it’s gonna be me.’ So, I really started thinking of the guitar as an instrument that does that. Everybody in the band, we can talk to each other with our instruments. It sounds really cosmic or like some sort of exalted state that I’m trying to front. It’s eternal, it’s a timeless thing that people have figured out [while] sitting on their porches in Appalachia, figured it out in the Sub-Saharan Desert.” but he doesn’t know how to explain to anybody what that really is.

There are a lot of motifs spread within the 10 tracks of Cousin, but the one that speaks the loudest is this idea of humanity and the binds that hold us all together, whether we recognize them or not. It makes me think about what Woody Guthrie was singing about 75 years ago. Tweedy says something in World Within a Song about “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five, that honest depictions of the world aren’t always sympathetically written about in popular music. As a writer, I’m always interested in using music and lyricism as a vehicle for better understanding the core connective tissue that we share with our neighbors and our loved ones and strangers, too. The way Tweedy puts it is “high-art journalism,” something that Cousin, in its most flourishing moments, taps into.

“There’s an authentic world that is very hard to see without art. I think that’s the main role of how books work, how records work, how paintings work—to snap people out of an illusion of the world, that they think they’re participating in, and open a window into something that’s more cosmic and real then we’re usually able to conjure on our own without it, without art,” he says. “Having a sincerely held belief that that is a worthwhile thing to contribute is pretty motivating. It’s pretty inspiring. I love being a part of that; I love that I, somehow, figured out how to keep reminding myself of that. And I like doing whatever small part I can to share it. The generosity of it, to me, is that people keep allowing me to do it. And that’s a responsibility, in a weird way. I don’t think people need Wilco records. They don’t need my songs. But, yes, they do at the same time. They need what it is they might be able to get from me. I don’t want to live with being one person that just stopped believing that.”

Every morning, Tweedy writes a song. It doesn’t matter if it’s good or bad; it’s the habit of getting something out of himself that didn’t exist before he woke up that’s become a sustaining, fulfilling practice. The byproduct of that is so wonderful and so rewarding that we might get to hear even a fraction of it. When Tweedy and I talk about his relationship to music with his sons, Spencer and Sammy, the way he describes what they’ve been able to achieve together—how the environment Tweedy and his wife Sue were able to foster, where making music wasn’t looked at as something Dad did for money, that it wasn’t just a job or something the next generation was expected to carry forward—it becomes clear that Cousin was an apt title for this new record after all.

“The end result is [Spencer, Sammy and I] get to have this ability to sit in a room and not talk, but have intimate trust in each other,” Tweedy says. “That’s what music is built on, an intimate trust in the people you’re playing with. We’re all going to the same place, and that’s beautiful. It’s profound, to get to share that with your children. For them, individually, they make music without me. And it’s just a beautiful thing, to watch them commune in a way that they grew up believing in.”

It’s a thesis statement for this chapter of Wilco, that the people we choose to make sense of the world with—be it our kin or our confidants—are what makes each day worth getting to, even if getting to that place isn’t immediately streamlined or easy. It sounds a lot like what happened when the band made Cruel Country at The Loft together in order to let the intricacies of Cousin continue to marinate beyond being just leaps of faith, and it sounds a lot like what happened when they reassembled to make Sky Blue Sky 16 years ago. It’s true, the world does need Wilco. The world needs these six people who put care and gentleness and curiosity and magic into their art and then have the guts to walk through the doors and back into the noise.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!