THE SONGS OF NANCI GRIFFITH

THE SONGS OF NANCI GRIFFITH

will be, forever, far more than a whisper

says Norman Warwick

Nanci Griffith (left) was a Texas singer-songwriter, the bulk of whose work is immediately identified with contemporary folk music. She has been recognized for her work as a songwriter as well as an interpreter of the works of of others.Throughout her career, Griffith flirted with popularity; but her fans seem to remain steadfast to this day, regardless of critical opinion.

At a time when popular music is, as Detroit News music critic Susan Whitall observed, “bankrupt of inspiration,” Griffith offers songs of love, stories of broken dreams, observations of people living lives that are neither heroic nor pathetic.

“The people residing within the lines of her songs,” Connoisseur reviewer Jared Lawrence Burden stated plainly, “are the salt of the American earth.” According to Stephen Holden of the New York Times, Griffith “sings lyrics redolent of the American landscape.”

Southern literature and folk music inform Griffith’s vision of this landscape. Born in Seguin, Texas, in 1954, Griffith described her family as “basically really dysfunctional,” to Texas Monthly. “I had very, very irresponsible parents.” Her father was a graphic artist and printer who sang barbershop quartet music. Her mother was a real estate agent who enjoyed jazz and tried her hand at acting. They divorced in 1960, soon after the family, (including two older siblings), had relocated to Austin.

Early Inspiration

Griffith grew up reading various writers and listening to jazz, folk, and country. When she was 8-years-old, Griffith says she learned to play guitar from an instructional program on public television.

She says it was, the voice of folk singer Carolyn Hester (right) , and the songs of country singer Loretta Lynn (below left) that imbued her with a passion for struggling human relationships, dreams, and a sense of place that she told Rolling Stone, instilled in her a desire to tell “incredibly vivid stories that hit their subjects right on the nail’s head.”

Nanci also added the name of the fiction-writer of Eudora Welty.(right) an American short story writer, novelist and photographer who wrote about the American South. Her novel The Optimist’s Daughter won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973. Welty received numerous awards, including the Presidential Medal Of Freedom and the Order Of The South

The combination of these influences gave rise to a unique Griffith style, which she termed “folkbilly,” and which the New York Times defined as a “songwriting style steeped in the rich mixture of Southern literary tradition, folk music, and country.”

l In Sing Out!, singer/songwriter Tom Russell (left) remembered his first encounter with Nanci Griffith at a folk festival in 1976. One evening around a campfire, with people spread out on a grassy hill into the darkness, guitars and wine being passed around, a gruff voice yelled from the darkness, “Let her play one.” From the edge of the campfire light came a waif-like young girl. She began to play and sing in a voice Russell said possessed “a wild, fragile beauty.” When she finished and the echo of the applause drifted away, the voice spoke again: “That was Nanci Griffith. She writes songs.”

When she began performing in the 1970s, it was at a variety of Austin nights spots–the Hole in the Wall and Alamo Lounge among them. In that period, Griffith was primarily singing the songs of others while working on her craft. She also began touring the coffeehouse and college circuit and promoting herself. Her earliest recordings were the independently released There’s A Light Beyond These Woods and Poet In My Window. Her break came in 1985, after appearing on the acclaimed television program Austin City Limits.

Also in 1985, Griffith moved to Nashville and soon was signed to a recording contract by MCA. Her first hit single was a version of Julie Gold’s “From a Distance.” (right) It was the number one song in Ireland. Artists including Suzy Bogguss and Kathy Mattea discovered Griffith’s music, which they would transform into hit songs. As Griffith continued in the music business, she chased success, opting to embrace a more pop sound with Storms and Late Night Grande Hotel.

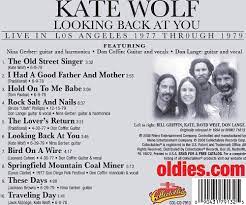

Griffith changed labels in the early 1990s, moving to Elektra subsidiary Nonesuch Records. Her first recording was 1993’s Other Voices, Other Rooms, a collection of other people’s songs that she had begun shortly after parting ways with MCA. She often said the inspiration for the project came while recording Late Night Grande Hotel. The songwriters whose work Griffith chose to perform on the project included many who informed her song-writing, including Bob Dylan, Townes Van Zandt, Woody Guthrie, Tom Paxton, and the late Kate Wolf.(left)

“All of these songs have a real special place in my heart. They speak of something dear to me in my musical and personal growth,” she told Billboard in a 1993 interview.

“Beauty and Dignity” in Her Songs

Griffith had a strong reputation for her song-writing. In Stereo Review Alanna Nash pointed out how Griffith crafts songs “focusing more on character development than outside events.” Burden offered a panorama of the focus in her songs: “There is a black middle-class woman living in Houston, caught at a moment of pride and wonder about her marriage. There is a couple arguing at the airport about their lost love. In one of her strongest and best-known songs, ‘Love at the Five and Dime,’ two lovers’ romance is rekindled by memories of the days when they were courting. The aim of these songs is not self-aggrandizement. In the best literary tradition, Griffith gives a voice to the inarticulate, the uninspired, the unheard.”

She told Paul Mather of Melody Maker, “I want to celebrate the South again. … There’s a dignity and beauty there that’s not often pointed out.”

Her celebration of life is not confined only to songs. When Griffith is not on the road, she writes stories and novels. So far she has completed one manuscript, Two of a Kind Heart, about three generations of a Texas family, and is working on a second, Love Wore a Halo Before the War. There is no division between the focus of Griffith’s songs and her prose. Often she turns a story into a song. “Love at the Five and Dime” was originally a short story while “Love Wore a Halo (Back Before the War),” which appears on Little Love Affairs, is drawn from the corresponding novel.

In concert, Griffith combines both mediums. She tells stories both through and between her songs. “Her stories,” Mather said, “are sometimes ordinary, sometimes magical, invariably enchanting.” He went on to add that “despite the often upbeat seduction, the lasting memory is of a beautiful sadness.” A reviewer for Variety was left with the impression of “an unusual talent, a winsome, almost strangely pure-voiced singer whose style and sound bear little taint of commercialization or contrivance, marked instead by a quirky, honest individuality and soulfulness that connect in gentle, often bewitching ways.”

Some critics, however, do indeed consider Griffith’s individuality to be contrived. According to Nash, there are some who deem her material “overly sentimental and precious, as affected as the white cotton anklets she wears with the old-fashioned dresses she makes from prints bought on sale from Woolworth’s.”

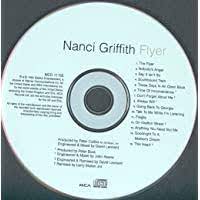

Flyer Utilized New Voices

Perhaps her most popular recording to date, 1994’s Flyer (left) featured a mix of rock and folk. She enlisted Peter Buck (R.E.M), Larry Mullen Jr. and Adam Clayton (both of U2), The Indigo Girls and others.

“I had always felt like maybe I didn’t have enough of an idea of who I was to write really personal songs, maybe because I was always on the road and never had a chance to sit back and get some perspective,” she told Billboard of her writing on the album. “Now I think I’ve gained a greater perspective, and this is probably the most personal set of songs I’ve written.”

Critics responded favourably to Flyer. “It’s a record that blends the quintessential folk style of Griffith’s … Other Voices, Other Rooms with the rock approach she explored on her last two albums for MCA,” wrote Billboard‘s Jon Cummings. “[I]t was as if working in the crucible of her influences had fired her muse,” wrote Hall in Texas Monthly. “The record had some of her best writing in years … plus smart arrangements.”

In 1996 and 1999, Griffith was diagnosed with cancer. First, with breast cancer, then thyroid cancer. And still, Griffith continued to be active as a touring and recording performer. She has also lent her celebrity to various charitable organizations including Campaign for a Landmine-Free World. Apart from these few insights, Griffith seems to be fiercely guarded about her personal life.

It would be several years before Griffith would record again. With such a long wait post-Flyer, expectations were high for Blue Roses from the Moons when it was released in 1997. It failed to connect with critics. Lyndon Stambler, writing in People said it “rarely reaches the heavens despite its fanciful title,” and found Griffith’s voice “lackluster and strained, disappearing at times behind the lush arrangements. In fact, no recording since the one-two punch of Other Voices and Flyer seems to have attracted positive attention from both critics and fans. She tried to recapture some of the magic of those with Other Voices, Too (A Trip Back to Bountiful), but it was deemed a poor imitation of the first covers collection. “[W]here the original was inspired, the sequel sounded, like its title, forced,” Texas Monthly‘s Hall. “Griffith–usually such a sure singer–sounded lost. She bent words unnaturally, self-consciously hammering them as if the eccentricity of interpretation would help deliver the meaning.”

Responded Vehemently to Reviews

In 1998, fed up with what she called “Years of Brutal Abusive Reviews,” Griffith wrote a puzzling, vehement letter to writers and editors at several major Texas newspapers–including the Houston Chronicle and the Austin Chronicle, which printed the letter in full–taking them to task for years of slights and abuses, without divulging any specifics. As Texas Monthly‘s Michael Hall wrote, the letter was “less a reply to brutality and abuse than an excuse to rant.” Even so, to those detractors she is seen as “a greeting-card folkie whose songs are full of sentimental caricatures and sweetness and light. Some go beyond her work and actually attack her personally. They see a faux na

The ´rant´ I received from Nanci was fully deserved and I apologised unreservedly when she telephoned me to complain about my review of a gig she gave in Manchester. The irony of this was that I was, and am, a huge fan of Nanci´s work, but on this occasion she suffered because I felt pretty disillusioned with music at the time.

I quite liked it when Nanci was singing those folkabiully songs to me and a growing, but still small number of friends. That night in Manchester was far removed from the previous Nanci shows I had seen in cosier and more intimate surroundings, convivial to her heart-spun songs. Here we were in, I´m not sure, but it might have been The Palace Theatre, at a sell out concert, in the kind of setting I had always hoped we might see Nanci and other folk-country writers. However, it felt to me, given my overall mood for that year or so, that this was a step too far. I criticised her for eschewing the five and dime and dipping into more important themes with songs like Hard Life.

What a bloody, unfeeling idiot I was to criticise an artist for being creative and exploring new paths. And Nanci told me that, but not so politely !!

Nanci Griffith´s career began with playing bars in Austin, TX, at age 14; After teaching kindergarten and first grade in Austin school system briefly during mid-1970s she first recorded for small Texas-based label, B.F. Deal, Her msical musical collaboration with her band Blue Moon Orchestra on he third album, Once In A Very Blue Moon, She subsequently won a Grammy Award, Best Contemporary Folk Album, for Other Voices, Other Rooms, ikn 1993.

My favourites among the twenty or so albums of hers I have on my playlists are

There’s A Light Beyond These Woods Philo/Rounder, 1978.

Poet In My Window Philo/Rounder, 1982.

Once In A Very Blue Moon Philo/Rounder, 1985.

Last Of The True Believers Philo/Rounder, 1986.

Little Love Affairs MCA, 1988.(featured John Stewart)

One Fair Summer Evening MCA, 1988.

Other Voices, Other Rooms Elektra, 1993.

Flyer MCA, 1994.

Other Voices, Too (A Trip Back to Bountiful) Elektra, 1998.

Clock Without Hands Elektra, 2001. (covered 3 John Stewart tracks)

Acknowledgement

The primary sources for this piece was written for the print and on line media by Rob Nagle and Linda Dailey Paulson. at

https://musicianguide.com/biographies/1608004219/Nanci-Griffith.html

Other contributing Authors and Titles have been attributed in our text wherever possible

Images employed have been taken from on line sites only where categorised as images free to use.

For a more comprehensive detail of our attribution policy see our for reference only post on 7th April 2023 entitled Aspirations And Attributions.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!