SKIP TO MY LOU my darling.

Jacob Uitti explains the meaning of

SKIP TO MY LOU my darling.

and Norman Warwick learns a lot.

When the esteemed magazine that is American Songwriter promises to deliver the hidden meaning behind a song, one assumes they are going to discuss a song of great importance and significance and that is very often the case. When doing so, though, they heed Wordsworth´s admonishment that we ´murder to dissect´ and avoid that trap of killing our enjoyment of the song by submitting us to factual overload. They also make us re-examine the notion that only ´ímportant´ songs have hidden meanings, and will occasionally look at what we might consider to be nursery rhymes. For today, though, come follow your art down sidetracks and detours,….and be ready to dance.

Jacob Uitti, writing for American Songwriter says that

For anyone who has gone square-dancing (left), the sights and sounds, melodies, and rhythms quickly become apparent. The activity is odd and fun, joyous and a bit hokey.

But most of all, the practice requires a specific type of soundtrack. Enter: “Skip Tto My Lou.”

In order to understand the fundamentals of square dancing, it’s important to understand the fundamentals and meaning of the songs that produce its score. So, let’s do just that.

Let’s go behind the meaning of the song, shall we?

The origins of “Skip to My Lou” and its meaning go all the way back to the 1840s. It’s what’s known in square dancing circles as a “partner-stealing” song and dance.

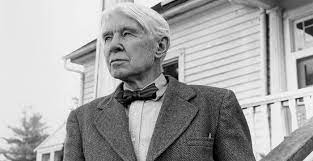

According to the poet and Abraham Lincoln biographer, Carl Sandburg, (right) “Skip to My Lou” was a song popular at parties in southern Indiana. While there are many verses that have been associated with the song, some common refrains include, “I’ll get her back in spite of you,” “Gone again, what shall I do” and “I’ll get another girl sweeter than you.”

In a time when partnership was prized and also aided by a little harmless flirting, the partner-stealing ode was a welcome bit of fun.

The dance associated with the song begins with a number of couples. They match up, touching hands and skipping around a ring. Traditionally, a lone young man stands in the center of the moving partner circles and sings the song, beginning, “Lost my partner, what’ll I do?”

Then things get a little more interesting.

The fella in the center begins to decide which girl he’d like to dance with, continuing his singing, “I’ll get another one just like you!” When he reaches out for the hand of his chosen lass, the girl’s partner moves to the center of the ring, taking the first’s place.

All of a sudden, young men are becoming acquainted with other young ladies and vice-versa. That is the meaning and the importance of the song and dance. It puts smiles on all who choose to enjoy the action.

Writer S. Frederick Starr has suggested that the song “Skip to My Lou” originally came from the Creole folksong, “Lolotte Pov’piti Lolotte.” The two songs bear a strong resemblance. And the word “lou” in the title and the song’s refrain comes from the Scottish word for “love.”

The term Creole music (French: musique créole) is used to describe both the early folk or roots music traditions of rural Creoles of Louisiana.

In 1803, the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory, including New Orleans, from France. In 1809 and 1810, more than 10,000 refugees from the West Indies arrived in New Orleans, most originally from French-speaking Haiti. Of these, about 3,000 were freed slaves.[8]

Creole folk songs originated on the plantations of the French and Spanish colonists of Louisiana. The music characteristics embody African-derived syncopated rhythms, the habanera accent of Spain, and the quadrille of France.

Central to Creole musical activities was Place Congo (in English: Congo Square). The much quoted 1886 article by George Washington Cable offers this description:

The booming of African drums and blast of huge wooden horns called to the gathering … The drums were very long, hollowed, often from a single piece of wood, open at one end and having a sheep or goat skin stretched across the other … The smaller drum was often made from a joint or two of very large bamboo … and this is said to be the origin of its name; for it was called the Bamboula.

Cable then describes a variety of instruments used at Congo Square, including gourds, triangles, jaw harps, jawbones, and “the grand instrument at last”, the four-stringed banjo. The bamboula, or “bamboo-drum”, accompanied the bamboula dance and bamboula songs. Chase writes, “For Cable, the bamboula represented ‘a frightful triumph of body over the mind,’ and ‘Only the music deserved to survive, and does survive … ‘”

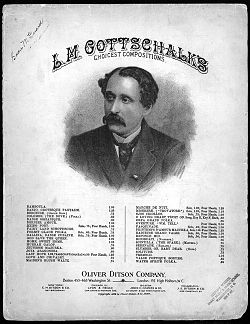

At the time of Louis Moreau Gottschalk‘s birth in 1829, ‘Caribbean’ was perhaps the best word to describe the musical atmosphere of New Orleans. Although the inspiration for Gottschalk’s compositions, such as “Bamboula” and “The Banjo”, has often been attributed to childhood visits to Congo Square, no documentation exists for any such visits, and it is more likely that he learned the Creole melodies and rhythms that inform these pieces from Sally, his family’s enslaved nurse from Saint-Domingue, who Gottschalk referred to as “La Négresse Congo”. Whether Gottschalk actually attended the Congo Square dances, his music is certainly emblematic of the crossroads that formed there.

Born in New Orleans and reared in the culture of Saint-Domingue, he toured throughout the Caribbean and was particularly acclaimed in Cuba. Gottschalk was closely associated with the Cuban pianist and composer, Manuel Saumell Robredo, a master of the contradanza, widely popular dance compositions based on the African-derived habanera rhythm. It is likely that contradanzas composed by both Gottschalk and Saumell were an antecedent to the ragtime compositions of Scott Joplin and Jelly Roll Morton.

Perone’s bio-bibliography lists hundreds of Gottschalk’s compositions. Among them are three solo piano works based on Creole melodies:

Bamboula, danse des nègres, based on “Musieu Bainjo” and “Tan Patate-là Tcuite” (“Quan’ patate la cuite”).

La Savane, ballad crèole, based on “Lolotte”, also known as “Pov’piti Lolotte”.

Le Bananier, chanson nègre, based on “En avan’, Grenadie'”, which like other Creole folk melodies, was also a popular French song.

In America’s Music (revised third edition, page 290),[12] Chase writes:

Le Bananier was one of the three pieces based on Creole tunes that had a tremendous success in Europe and that I have called the “Louisiana Trilogy”. [The other two are Bamboula and La Savane.] All three were composed between 1844 and 1846, when Gottschalk was still a teenager … The piece that created the greatest sensation was Bamboula.

Chase apparently overlooked a fourth Creole melody used by Gottschalk on his Op. 11 (Three other melodies had already been identified for this piece). In her 1902 compilation, Gottschalk’s sister, Clara Gottschalk Peterson, arranged “Po’ Pitie Mamzé Zizi”, and included a footnote: “L. M. Gottschalk used this melody for his piece entitled Le Mancenillier, sérénade, Op. 11.

“Regarding “Misieu Bainjo”, used in Gottschalk’s Bamboula, the editors of Slave Songs write “… the attempt of some enterprising negro to write a French song; he is certainly to be congratulated on his success.” The song has been published in more than a dozen collections prior to 1963, listed by the Archive of Folk Culture, Library of Congress.

Songs numbered 130-136 in Slave Songs of the United States, according to a note on page 113, were obtained from a lady who heard them sung, before the war, on the “Good Hope” plantation, St. Charles Parish, Louisiana … Four of these songs, Nos. 130, 131, 132, and 133, were sung to a simple dance, a sort of minuet, called the Coonjai; the name and the dance are probably both of African origin. When the Coonjai is danced, the music is furnished by an orchestra of singers, the leader of whom—a man selected both for the quality of his voice and for his skill in improvising—sustains the solo part, while the others afford him an opportunity, as they shout in chorus, for inventing some neat verse to compliment some lovely danseuse, or celebrate the deeds of some plantation hero. The dancers themselves never sing … and the usual musical accompaniment, besides that of the singers, is that furnished by a skilful performer on the barrel-head-drum, the jaw-bone and key, or some other rude instrument. … It will be noticed that all these songs are “seculars” [not spirituals]; and that while the words of most of them are of very little account, the music is as peculiar, as interesting, and, in the case of two or three of them, as difficult to write down, or to sing correctly, as any [of the 129 songs] that have preceded them.

The words “obtained from a lady who heard them sung” suggest that the songs were written down by someone, perhaps the lady herself, but certainly someone adept at music notation who was able to understand and write down the patois. It seems likely that she or he was a guest or a member of the La Branche family, who resided at the plantation until 1859, shortly after which the plantation was devastated by flood. This family included United States chargé d’affaires to Texas and a Speaker of the Louisiana House of Representatives, Alcée Louis la Branche.

We may never know the identity of the person who wrote down the seven Creole folk songs as sung at Good Hope Plantation, but it is noteworthy that Good Hope (town), Good Hope Floodwall, Good Hope Oil and Gas Field, Bayou La Branche, and, especially, La Branche Wetlands are today well known names in St. Charles Parish, where the seven songs were once sung.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Camille Nickerson performed Creole folk music professionally as “The Louisiana Lady”. During an interview with Doris E. McGinty, Professor Nickerson told of her first performance at a parish in New Iberia. “I was dressed in Creole costume and sang for about an hour and a half, and was very well received. Now this was a white audience; such a thing was unheard of in Louisiana, especially in the rural section such as this was. The enthusiasm of the audience showed me what an impact the Creole song could have.”

So, we seem to have dug deep down into the roots of Skip To My Lou, and have perhaps identified some of the routes the song had to follow to become the one my generation recognises today.

That is in no small measure due to a music score attributed to Dan Coates that seems to have attracted artists like Judy Garland, Burl Ives and Nat King Cole.

Mr Uitti´s article brought to mind memories of the 1970´s when in the UK the song was adopted by at least one professional football club and its fans in the UK. Celebrating goals by their impish little inside forward Manchester United would sing the tune to celebrate ´goals from Lou Macari´!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The primary source for this piece was written for the print and on line media by Jacob Uitti for American Songwriter. Authors and Titles have been attributed in our text wherever possible. You can find details on line on how to subscribe to the excellent American Songwriter

Images employed have been taken from on line sites only where categorised as images free to use.

For a more comprehensive detail of our attribution policy see our for reference only post on 7th April 2023 entitled Aspirations And Attributions.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!