CUP FINALS EVERY NIGHT

First Team To Ten ¨d Bring Álf Time

when Norman Warwick and Colin Lever played

Not only do I remember Going To The Match, but I also remember going to the cup final,….every night. In fact, I remember playing in the cup final,….every night. I remember it like it was just the other night,

when school bell rang at four o´clock,

it were off wi´ the tie, and down wi ´yer socks

and skip yer ´omework ´n leave yer tea´

and go out ´n play for Wanderer´s FC

we were good for nothing boys, a group of ragamuffin boys

and our lamp-posts was like Wembley´s brightest floodlights.

We were stars wi´ twinling feet,

playing at Wembley on a cobbledy street.

Playing our cup finals every night.

I remember how

two big lads ´d pick two teams

(and I was always last one picked, it seemed,)

even though there p´raps be fifteen lads each side,

and first team to ten ´d bring half time,

then just as match were tensely poised

out came owd Granny Éap, ¨what´s all this noise?

and wei´the score at nineteen all,

she´d beggar off back in and tek the ball !

Cup Finals Every Night recorded by Lendanear

© Lever / Warwick Lever 1979

www.lendanearmusic

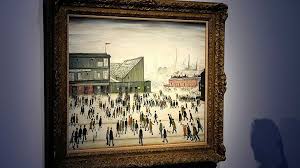

I remember Going To The Match when I was a kid with my dad to watch United, and I remember going to The Lowry, when I was young married man, to see Going To The Match (left) , which has been on display in the theatre and art museum in Salford since 2000, before being sold to raise money for the new body.

A spokesperson for the Players Foundation said: “We are very proud that we have been able to make sure the British public have had the opportunity to enjoy such a wonderful piece of footballing memorabilia and art.

“The Players Foundation no longer has any income guaranteed, so we have had to completely reposition the charity. The trustees recognise the current financial crisis means we need all the income we can obtain, and all our assets have to work for us to ensure our ongoing work.

“We want to continue to provide, amongst other things, benevolent grants to those in real financial need, and assist people with dementia. This has led us to the inevitable decision that the Lowry has to be sold in the interests of our beneficiaries.”

The current record price for a Lowry is held jointly by another football painting, The Football Match, which sold for £5.6m in May 2011, and a painting of Piccadilly Circus, which also sold for £5.6m six months later.

They stream towards the turnstiles, stick-like figures instantly familiar to anyone who has looked at a painting by LS Lowry.

In the foreground, their coats and hats are distinct. In the background, beneath the tall chimneys of a long-gone heavy industry, the people are a blur. But all of them have a common purpose: going to the match.

At the time of writing this article the painting by one of Britain’s best known and best loved painters, is set to smash records when it is put up for sale to raise money for a charity that helps professional football players.

Going to the Match, painted by Lowry in 1953, is expected to fetch up to £8m. It was last sold in 1999, when the Professional Footballers Association (PFA), the union for current and former players, paid £1.9m.

Lowry only took up painting full-time after retiring from his job as a rent collector in 1952. Before that, he generally painted late at night after his mother, with whom he lived, had gone to bed. A modest and reserved man, he turned down five separate state honours during his lifetime, including a knighthood in 1968.

The artist, famous for his industrial scenes in the north-west of England in the mid-20th century, produced a number of football paintings, of which Going to the Match is the best known.

“What they’re really about is humanity,” said Nick Orchard, head of modern British and Irish art at Christie’s, which is auctioning the painting in London next month.

“Going to the Match is about emotion, excitement, the crowd gathering, the group experience. In the industrial north-west, most workers in the mills would probably do a five-and-a-half-day week, clock off lunchtime on Saturday, off to the match Saturday afternoon, and that was the beginning of their break from working life.

“Lowry was a great observer of people, particularly within the industrial landscape, and these football matches really captured the essence of what Lowry was trying to get to in his paintings.”

The stadium in the painting was Burnden Park, the home of Bolton Wanderers, close to Lowry’s home in Pendlebury. (The artist was a lifelong supporter of Manchester City.) Thirty-three fans were crushed to death at Burnden Park in 1946 in one of the worst stadium disasters of the last century. It was demolished in 1999, and the site is now a retail park.

I actually worked at Burnden Park in the police control room for fifteen years as a match day cctv operator, and indeed worked with Bolton for a further twelve years in the same post after their move to the initially named Reebok Stadium (in Horwich) and which has since been called just about any other name you could think of.

The ´new¨ stadium has its statue of Nat Lofthouse (right) at the front entrance and we fans are hopeful the venue will yet create a history to match that of Burnden !

The work b y LS Lowry (left) shows the old stadium in all its glory. as well as the crowds flocking to the turnstiles, the painting shows crowded terraces inside the ground, and surrounding terraced homes as well as the factories in the background. “He’s packed it all in,” said Orchard.

When the PFA paid £1.9m, more than four times the estimate, for Going to the Match in 1999, Gordon Taylor, then chief executive, said it was “quite simply the finest football painting ever.” It would be the PFA’s “prized possession”, he added.

The PFA’s charitable arm recently became a separate body, the Players Foundation, under a reorganisation prompted by a warning from the Charity Commission. It helps players and former players with matters including education, pensions, health and legal issues.

The advice and decision to sell the painting proved such a complete success, that Bolton fans echoed Skinner and Baddiel´s hit-turned-terrace-hant that, It´s Coming Home when the details of the auction were released.

Jacob Whitehead reported that ´The clock hits 6.30pm, the auctioneer hits the gavel, and the most famous football painting in history is up for sale.

Christie’s west London headquarters is filled with collectors, critics and journalists, the majority waiting for the ninth lot of the evening — LS Lowry’s Going to the Match.

Telephone bidders flank the room. A giant screen showing prices in eight currencies casts a ghostly light. Lowry’s painting, hung to the right of the rostrum, is under a spotlight.

The painting was bought by the Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA) in 1999, then given to the Players Foundation, formerly the PFA’s charitable arm and now a separate organisation. The controversy is over where it goes next.

The PFA put the painting up for sale this year due to the rising pressures of the financial crisis. With the placement of Going to the Match in the Lowry Art Gallery’s collection at risk, the mayor of Salford, Paul Dennett insisted it should remain “free to access”.

Dennett started a public campaign to keep the painting in the public’s hands.

“LS Lowry, Salford’s greatest and most iconic artist, made his name depicting working-class life – as such we emphatically believed Going to the Match should remain on public view free to access where everyone can see it,” he said.

The gallery was able to make the astronomical bid – £6.6m with a buyer’s premium of £1.2m – thanks to a donation from the Law Family Charitable Foundation.

Estimates for the sale ranged from £5m to £8m.

For now, the Lowry will stay at The Lowry.

cover

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!