REVEREND RICHARD COLES has books to write

REVEREND RICHARD COLES has books to write

by Norman Warwick

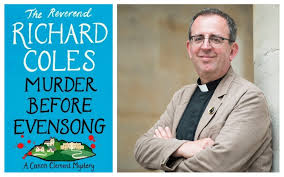

People of younger generations than mine have cause to remember the pop-hit career of a singer we now refer to as Reverend Richard Keith Robert Coles FRSA FKC (born 26 March 1962)[1] is an English writer, radio presenter and Church of England priest who was the vicar of Finedon in Northamptonshire from 2011 to 2022. He first came to prominence as the multi-instrumentalist who partnered Jimmy Somerville in the 1980s band the Communards. They achieved three top ten hits, including the No. 1 record and best-selling single of 1986, a dance version of “Don’t Leave Me This Way“. he is a man who follows his heart, so let´s follow our art down sidetracks & detours and maybe we can step into a church, we find along the way, get down on our knees and begin to pray and to begin California Dreaming,….

Reverend Richard Coles frequently appears on radio and television as well as in newspapers and, in March 2011, became the host of BBC Radio 4‘s Saturday Live programme. He is a regular contributor to QI, Would I Lie to You? and Have I Got News for You. He is an author, Chancellor of the University of Northampton, Honorary Chaplain to the Worshipful Company of Leathersellers, and a patron of social housing project Greatwell Homes in Wellingborough.

Coles learned to play the saxophone, clarinet and keyboards and moved to London in 1980, where he played in theatre. In 1983, he appeared with Jimmy Somerville in the Lesbian and Gay Youth Video Project film Framed Youth: The Revenge of the Teenage Perverts, which won the Grierson Award. Coles joined Bronski Beat (initially on saxophone) in 1983

Somerville left Bronski Beat and in 1985 he and Coles formed the Communards,who were together for just over three years and had three UK top 10 hits, including the biggest-selling single of 1986, a version of “Don’t Leave Me This Way“, which was at number one for four weeks. The band split in 1988 and Somerville went solo.

Perhaps, as I did, many others of my generation of seventy year olds, who ran away scared of punk the seventies suddenly ound the music of the Communards and Bronski Beat quite palatable, and many of us now think of Reverend Richard as that nice young man off the telly, you know the one,…religious bloke but doesn´t throw it in your face, nice sense of humour, tells some good stories,… you know the one in all the light entertainment shows.

And now all of he is attracting a new audience as a writer of novels. He is all over this month´s edition of my Writing Magazine to which I have subscribed for over fifty years now. It is a magazine that provides information, workshops, exercises and competitions for aspirant writers, and contacts and interviews and articles with established authors,…just to further remind we hacks still sitting at our tripe-writers how far we still have to go.

However, it was in another literary magazine, Writing, that I first heard of Charlotte Eyre (right). She is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children’s books previewer. She has programmed the annual The Bookseller Children’s Conference and launched The YA Book Prize in 2014, and is a regular guest on radio programmes such as “Open Book” on BBC Radio 4.

The Bookseller published an article by her, on the afore-mentioned Reverend Coles, in March of earlier this year. She introduced the article by saying that

with the release of his 1980s-set murder mystery novel on the horizon, Reverend Richard Coles talks crime, compassion and his plans for the series.

There is an “enormous” appetite right now for crime fiction, says the Reverend Richard Coles from his parish in Northamptonshire, where he is speaking via Zoom about the first book in his new series (and his first fiction publication), Murder Before Evensong (Orion).

“It offers some kind of reassurance,´ he muses. “It gives you familiarity in a world that grows unpredictably strange, and resolutions. We most often find out what happens in the end.”

Murder Before Evensong, (left) Charlotte tell us, is about Canon Daniel Clement, Rector of Champton, who lives at the Rectory with his widowed mother and two dachshunds. The year is 1989, and the novel starts with Daniel telling his congregation that he wants to install a loo in the church, which doesn’t go down well with everyone. And when one of his flock is found dead at the back of the church, stabbed in the neck with a pair of secateurs, Daniel suddenly has more to solve than arguments about lavatory arrangements.

All of the characters any readers could want to see in an English pastoral novel are here: the local landowner, his archivist cousin, the county councillor, the head teacher of the primary school… and of course the choir singers, flower arrangers, organist and PCC (parochial church council) members who keep the church running. In terms of influences, Coles mentions G K Chesterton and Marjorie Allingham. I saw something of Barbara Pym in there too.

He stresses that he is not Daniel, despite also being a vicar who owns dachshunds.

“He’s much steadier than me, and he’s more heroic. He’s quietly heroic and I’m not even that. He’s also much fussier than I am.”

People who know Coles, however, might see one or two resemblances between his mother and Audrey, Daniel’s clever and opinionated mother, he says, but mostly the inspiration for his characters came from watching the community around him.

A line in the press release says: “NB: No parishioners were harmed in the writing of this novel.”

“If you are a vicar, you get used to being part of the community, and reading the community in a particular way, which is why I think vicars make good detectives,” Coles says. “We are nosy people by nature and our job is to kind of look at things, and look at people, and try to match what appears on the surface with what happens underneath.”

Vicars meet and speak to people from all parts of society (“you can spend the morning in a prison and the evening with a duke”, he quips) and are witness to problems and arguments that come with that.

“One of the interesting things you see in church life all the time, especially in rural church life, is all sorts of tensions play out. At the moment, what we are seeing in rural churches are Brexit tensions playing out. We are a diverse community and we have very different views. That fascinates me. On a good day, we model how you might live together in disagreement. On a bad day, we model how you don’t live together with disagreement.”

Coles is equally good at the big stuff as well as the daily life of being part of a church community, and the squabbles the latter provokes. He is—unsurprisingly—excellent at portraying a certain kind of English churchgoer. The ladies who do the flowers are described as having become “flowery to the exclusion of everything else”, wearing “related—if not quite matching—floral-print Sunday dresses, bought at cost from Mrs Harper’s shop.”

His portrayal is affectionate, but not without satire, and it feels like there is a lot of compassion from Daniel and his creator for these people. The reader is left with the understanding that Daniel, like Coles, is leaving condemnation and judgement to the Lord. We see and understand why people act the way they do, and I felt almost sorry for the murderer when the denouement is revealed, because of what happened in their past.

Coles says: “I’ve worked with prisoners who were coming to the end of sentences for terrible crimes. The kind of crimes for which there is no forgiveness, I think, but when you get to know people and you walk alongside people with that kind of history, you don’t have to go far back to see they were victims too before they were aggressors. Once you get that sort of picture of people it’s hard not to feel compassion… We must judge as we would wish to be judged, and that is with compassion.” Crime novels also express a reality—that life is all light and shade,

Charlotte asked why set the book in the late 1980s?

It was a “hinge” moment in British history, he says. There were a lot of people at that time who had been through the Second World War and were traumatised by their experience of it, and at the same time things we take for granted today, such as LGBTQ+ rights, were just beginning to happen. And in terms of the church, that period was when the old model of having one vicar in the parish as a settled and steady presence was also starting to fall away, and at the end of the book Daniel is told he needs to take on additional parishes as well as his own. That does, of course, set up book two nicely, but it also shows a system that had been in place for centuries was starting to be dismantled.

Murder Before Evensong will be published in June, just after Coles retires from his parish. His husband David died two years ago (as detailed in his 2021 memoir The Madness of Grief (W&N)) and Coles realised then that he would need to move away and start a new kind of life.

He is moving to the South Coast, to a village, that he told Charlotte is “rich in potential for murder mystery”, where he will continue writing the Canon Clement Mystery series. He jokes that he might write 40 books but has so far signed up to do three, a “nice Trinitarian number”.

The second novel is already written, and tells how Daniel has to oversee new parishes up the road and deal with a new arrival who comes from a different church tradition. And book three´s murder might be set on a film set, with the big house being used as a backdrop.

Charlotte describes Daniel as currently an Agatha Christie-type detective who doesn’t seem to have any interest in forming romantic attachments. Whe she asked if that might change Reverend Richard Coles took a vow of silence !

Charlotte could her tell Bookseller readers, however, that in writing these books he is having a wonderful time.

´It’s been a real a real challenge to try and do it myself, but I have really enjoyed itI find that between 5,000 and 10,000 words it starts to write itself… It has an energy and dynamic of its own. It’s an extraordinary feat of organisation, writing fiction. I’ve got friends who are fiction writers and I marvel at their capacity to keep the architecture and the detail together in their heads.

acknowledgements

The primary source for this piece was written for the print and on line media magazine Bookseller by Charlotte Eyre, and in Writing magazine. Authors and Titles have been attributed in our text wherever possible

Images employed have been taken from on line sites only where categorised as images free to use.

For a more comprehensive detail of our attribution policy see our for reference only post on 7th April 2023 entitled Aspirations And Attributions.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!