Julien Baker STARTING OUT SMALL; GETTING BIGGER.

Julien Baker

STARTING OUT SMALL; GETTING BIGGER. Norman Warwick learns about her from a trusted source.

It is some while ago now that I had an e mail exchange with Sidetracks And Detours reader, and fount of all knowledge Americana, Peter Pearson about what I felt was a dirth of female singer writers on the scene. Where is the next generation who will take on the baton from the likes of Katy Moffatt, Nanci Griffith and Gretchen Peters I asked Peter in near-desperation. The list he sent me of new writers he was excited about was long enough to make me realise there were too many people I had overlooked or, in some cases, even been aware oof whom I had never been aware, and I realised I was goping to need more storage space for my playlists.

In covering such a breadth of music here at Sidetracks And Detoruurs, as well as all the other arts forms and events we try to keep reader informed of, we sometimes find an artist has slipped through our net. However diligent readers like Peter Pearson, and excellent writers at the professionally resourced sites like Geoffrey Himes at Paste on-line bang sign-posts into the ground pointing to any sidetracks & detours we haven´t taken.

Geoffrey Himes opened a recent piece of his in Paste On Line with an acute observation.

´When songwriters come up with new material´, he said, ´we’re used to experiencing the songs twice: first as studio recordings (audio and/or video) and then as live performances. But in addition to everything else, the pandemic disrupted this pattern and often left us hanging, waiting for the second shoe to drop.

So it was that Julien Baker could release one of the year’s best albums, Little Oblivions, in February and not do a proper tour for more than six months. That tour finally begins this weekend, September 3-5, with shows in Alabama and Georgia (though the Bonnaroo Festival, where she’d been set to perform Sunday, was canceled due to flooding this week). Baker did do a handful of pop-up shows in her current hometown of Nashville last spring, and she did appear at the Newport Folk Festival on July 28.

Sidetracks And detours disseminated some reports a couple of weeks ago of what sounded like a very successful festival, and readers wanting an overview can still find our posts of Newport Folk-On Festival, and Newport Where Dylan Plugged In filed in our music archives.

Mr. Himes claimed that the Newport set by Julien Baker was revelatory, ´for it allowed the singer to present her songs in an unplugged format where every lyric subtlety and every melodic nuance could be clearly heard. And it allowed Baker, sitting in a plastic folding chair, her dark red hair parted in the middle and flowing over her gray T-shirt, to banter informally with the audience.

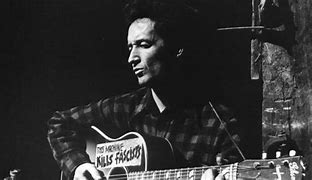

Woody Guthrie famously had a bumper sticker on his acoustic guitar that read, “This Machine Kills Fascists.” On hers, Baker had little white stickers that spelled out, “Queer Joy.” At Newport, she explained the motto as she introduced the song “Rejoice”: “I put ‘Queer Joy’ on both my instruments, because people kept saying my songs were sad. But I’m really joyful and happy about a future where queerness is just a part of life.”

She then played that song from her 2015 debut album, Sprained Ankle, with strong but patient chords, and a voice that started in the trembling whisper of a confided secret and climaxed in a bellowed declaration. The lyrics began with a bleak description of homeless teenagers sleeping on a bench or in a plastic bag near the train tracks, wondering what’s worse: the daze of addiction or the shakes of withdrawal. But as her vocal gained power, the song’s attitude shifted, and soon she was addressing a deity directly, arguing that her complaints are a kind of prayer, that knowing those prayers are heard is reason to “rejoice.”

Geoffrey now recognises this as a familiar tactic by Baker:

´She often moves back and forth between private thoughts and public testifying, between a depressing present and a better future, between despair and hope, between quiet music and loud.

“That’s a trope I recognize in my music,” she says over the phone from her home in East Nashville. “I start out small and then get big and then turn small again. Maybe I have to have moments of being introspective and withdrawn to justify a noisy song like ‘Hardline.’ That’s the kind of song I grew up with, but there’s a part of me that wants balance. I usually performed solo during the first two records, so I had limited instrumentation. But on the crescendo parts, sometimes people would sing with me, and that felt sort of like camaraderie.”

Himes reminds readers that, at Newport, Baker presented four songs by herself, then brought out Mariah Schneider, the other vocalist and guitarist on Little Oblivions, for five songs before finishing up by herself. Baker even played banjo on three tunes.

“I’m a hobby banjo player,” she told the crowd. “I’m trying to reconnect to my Appalachian roots, so I thought I’d bring it to the Newport Folk Festival. But I forgot there’d be some really good banjo players here.”

The Paste reported noted this as the kind of self-deprecating humour that lightened the darkness of so many of the songs and restored the balance she’s been seeking. ´There was humour in the way she conflated drugs and religion on Faith Healer, another new song she sang at Newport. When she conversationally sang, “I miss the high, how it dulled the terror and the beauty,” it wasn’t clear if the intoxication came from whiskey or the Bible—or if it even mattered. After all, is the faith healer all that different from the snake oil dealer?´

“The intention of Faith Healer,’ she confirms, ´was to write about intoxicants from the point of view of a sober person who’s started to use again and recognizing the similarities with religious experience. Substances are neurological and psychological, and religion can become a psychological impediment, which can become neurological. Both can be fun and provide you with a lot of comfort, but if they’re not used wisely they can quickly become destructive. I don’t know how to balance that, but I’m trying.”

The twin themes of drinking and religion are identified by Himes as the thread that runs through Little Oblivions, and give the album its title.

´The record opens with churchy organ, followed by Baker’s admission that she “blacked out on a weekday—is there something I’m trying to avoid?” When the organ is replaced by brittle, indie-rock guitar, she sings louder: “I’ll split the difference between medicine and poison, take what I can get away with.”

She didn’t perform Hardline at Newport, but she did sing the album’s next and scariest song, Heatwave, which imagines what it would be like to put “Orion’s belt around my neck and kick the chair out.” The temptation to suicide is made all the more alluring by a spooky, electric-guitar figure on the record; onstage, it was normalized by the back-and-forth between Baker’s banjo and Schneider’s acoustic guitar.

They also skipped Relative Fiction, which continues the new album’s suicide theme with the couplet, “You could see me dangling, glow like a cherry.” And yet this song uses its loping rhythm and lazy, catchy guitar figure to reach some hope at the end. “I don’t need a savior,” she declares. “I need you to take me home.” Whether the savior is Jesus or a would-be, white-knight lover, the narrator has an epiphany: She can no longer live up to impossible standards of salvation and damnation. She’s “finished being good”; now she can just be OK.

´Relative Fiction is very bleak´, Baker admits, ´but it’s very bouncy and uplifting musically. There’s a sadness when you discover your life’s not going to be what you thought it was going to be, but there’s something healthy about that. I don’t want to say that hope is foolish, but it can be naïve. I was reading this thing about how nihilism and romanticism can both paralyze you from action. Reasonable hope is believing that human beings are resilient and we’re capable of overcoming challenges´.

Ever the questioner, Geoffrey asked her for an example of reasonable hope.

´You can think´, she replies, ‘I’m not going to vote because it’s already decided.’ Or you can think, ‘I’m not going to vote because it’s all going to work out in the end.’ Both thoughts stop you from acting. Do I think there’s going to be a president who will eliminate poverty in a single four-year term? No, but voting, praying, recycling are all things I still do, even if people say they don’t matter. Because you have to practice hope to make it real´.

´The path she takes from despair to hope in Relative Fiction is travelled by her savvy use of juxtapositions and dynamics in her arrangements. The drum loop is harsh and industrial, but the guitar parts are relaxed and friendly. When the loop disappears, she can sing quietly and intimately. When the loop returns with a swooshing synth in tow, she raises her voice to make sure she’s heard over “the drunks at the bar [who] talk over the band.”

´On this record,” she argues, ´when a song reaches a musical climax, I feel like there’s some anger in it, like shouting out of desperation, allowing myself to get loud. That is how I try to write songs, with an audience in mind, to insinuate some positive moral to the suffering described in the song. On this record, it felt better to just document the suffering without feeling beholden to the audience to turn it into an anthem of recovery. The blessing and the curse at the same time sounds trite, but it allowed me to step back from the audience and just speak for myself´.

´But at the core of Little Oblivions´, her interviewer suggests, ´is her inventive use of words, which describe not only the walls closing in on her, but also create the door to get out. It’s as if she wrote her way out of a very dark place. As she sings in Relative Fiction, “I try to express / I can’t understand / I beat at the keys / I bloody my hands / till you hear me.” She had felt lost when exhaustion and then the pandemic pulled her off the treadmill of touring, but writing about it helped´.

´I was doing 250 shows a year for four years´, Baker explains, ´and I didn’t know who I was when the wheels slowed down. I’m a musician who writes songs, and suddenly it became my profession. My friends and the people I work with encouraged me to take some time off and take care of myself. I didn’t know how to take care of myself. I was in an unstable place; I wasn’t healthy enough to continue to keep touring.

I thought I wasn’t sure I’d want to keep touring and maybe I’d need a degree for another job. So I went back to school I was being asked in interviews at age 20 to talk about queerness and God, two enormous topics. It was nice to just learn and inform myself. Being a student and not a performer helped me reconnect to why I became a performer in the first place. When it wasn’t my job and I was just writing songs, I was making songs because it was fun; it made my soul feel good. It was a safe place to put my feelings´.

´Once she decided to unblinkingly examine her fall from sobriety´, Mr. Himes tells us, ´and her doubts about religion and her career, she began to find strength in metaphors and the economical phrases that have always been her trademark. On Cry Wolf, she condenses a whole season of inebriation as one particularly disastrous New Year’s Eve party. On the first morning of January, she awakes feeling as if someone has shoved a charcoal briquet down her throat, as if everything she was sure of has floated out the window like last night’s cigarette smoke.

On Highlight Reel, she describes herself as “passed out in the back of the cab,” unsure if the cab has driven off a bridge into the river or if it just seems that way. On Favour, the narrator’s sitting on the hood of a car, drunk and bored in a parking lot, when her friend saves a moth caught in the grill of a truck. The narrator asks why it’s easier to be tender “with anything less than human.” The sentences are elliptical; the rhymes are more suggestive than perfect; the scraps of dialogue and description dare the listener to fill in the gaps.´

´I’ve always liked words´, Baker confesses. “I never enjoyed math and science. I like writing and reading, learning how to use language in a way that’s beautiful. Poetry allows you to step outside the boundaries of academic language or everyday language. That was always attractive to me. Doing close readings of poems in college made me a more intentional songwriter and listener. I consider listening to music all the time as part of my job. I always ask questions: ‘Why did they use this language? Why did they use this chord?´

The journalist believes that one of the best songs on the new album is named after its anchoring chord: Song in E.

´In the studio, it was a piano ballad with a classic Tin Pan Alley melody to match, even as the lyrics describe the bottommost depths of her depression. At Newport, she sang it with just her acoustic guitar, but the tune was just as captivating and her claim that she’s not fishing for pity just as insistent. Maybe she’s addressing a girlfriend; maybe she’s addressing a Supreme Being, but her message is the same: “Give me no sympathy / It’s the mercy I can’t take.”

Another widely respected music journalist, Mark Hogan, writing at the on-line site, Pitchfork, suggests Julien Baker turns being way too hard on yourself into its own genre. The Tennessee singer-songwriter and producer’s debut album, 2015’s Sprained Ankle, delivered gut-wrenching tales of injury and substance abuse while setting Baker’s prayerful voice over little more than twinkling acoustic guitar and a smattering of piano, with a title track that echoed Baker’s real-life experience of running herself ragged. Her follow-up (and Matador debut), 2017’s Turn Out the Lights, added woodwinds, strings, and other flourishes, but at its emotional core was a lone character convincing herself just “not to miss any more appointments.”

With Baker’s third album, Little Oblivions, her self-lacerating storytelling gets a more expansive canvas. Maybe the blockbuster success of Olivia Rodrigo’s “drivers license” has turned the emotionally specific introspection of young women into pop’s latest zeitgeist, but Baker has been doing this all along. The 25-year-old has become a de facto generational spokesperson who grew up gay, Christian, and hardcore in the American South and survived teenage addiction. Her profile has enjoyed an extra boost lately thanks to the triumph of 2018’s self-titled EP by boygenius, her supergroup with Lucy Dacus and Phoebe Bridgers. Over the past several months, in a grueling gauntlet of fascinating interviews, Baker has talked openly about the relapse and heartbreak that inform her new record, where she hones her craft during a notoriously difficult time.

´On this new record´, Baker says, ´there’s a lot of self-indictment. When I’m singing that way, it could sound like I’m seeking approbation, but I’m not. It’s more exhausting to try to deceive myself or to manipulate others into thinking what’s not true than to admit I have flaws. This is true in my personal relationships too. Sometimes I listen to my older songs, and I say, ‘Listen to you, 18-year-old Julien, poor you. You have problems with your parents or someone you like doesn’t like you, like you’re the first one that ever happened to.’ I laugh sometimes, because that makes it bearable´.

Although Baker still plays nearly every instrument herself, the biggest change on Little Oblivions is a full-band sound. The shift is most jarring on opener “Hardline,” where organ-like whorls are upended by newfound rumbling, but it’s restrained in a way that softens the sting of a song that begins with Baker’s narrator “blacked out on a weekday” and ends with her asking, “What if it’s all black, baby, all the time?” The jaunty banjo that opens the next track, “Heatwave,” is a much-needed breather before Baker darkly vows, “I’ll wrap Orion’s belt around my neck and kick the chair out.” Particularly given all the mannered singer-songwriters springing out of Indieville in recent years, the jolt of distorted guitar on “Ringside” feels as welcome as the central image is unsettling: “Beat myself till I’m bloody, and I’ll give you a ringside seat.”

A more significant and nuanced development is Baker’s growth as a songwriter and vocalist, particularly noticeable on the piano ballads. Where her melodies once seemed more like vehicles for her words, fine-tuned for emo singalong refrains, on “Crying Wolf” she soars with a dignified aplomb fit for an Oscar contender’s closing credits—never mind that it starts out with another unnerving line: “Day-one chip on your dresser, get loaded at your house.” The album’s musical peak and emotional nadir is another slow, keyboard-based track, “Song in E,” which throws in a fancy chord or two as Baker’s narrator fesses up to having only herself to blame for her drinking, then twists the dagger into herself even further: “It’s the mercy I can’t take.” Over and over again on Little Oblivions, the paradox is that Baker’s craft is most realized when her lyrics are most disturbing.

As skilled as Baker is at this tasteful bleakness, it’s still not easy listening. Reunited with boygenius bandmates Dacus and Bridgers, who lend swooning vocal harmonies to “Favor,” she implores, “What right had you not to let me die?” There’s a huge, thrumming chorus on “Relative Fiction,” but it’s not the feel-good sort (“I don’t need a savior/I need you to take me home,” she insists). Baker’s trauma may not be yours, but if you can recognize a piece of yourself in her soul-searching and despair, Little Oblivions can be surreptitiously devastating.

Since Sprained Ankle, when a 19-year-old Baker sang, “Wish I could write songs about anything other than death,” her work has had an interesting meta quality. Here that’s manifested on “Faith Healer,” a bristling radio-rock anthem that I hear as commenting on the seductiveness of not only drugs, religion, and sex (little oblivions, indeed!), but also the Total Entertainment Forever that is today’s opiate of the masses. Artists are unfairly held up as saviors, especially in an always-on social media world fixated on portrayals of authenticity. Turn Out the Lights ended with Baker proclaiming no difference between demons and saints. Little Oblivions closes, on the trudging “Ziptie,” with an even more bracing dose of iconoclasm: “Good God, when’re you gonna call it off/Climb down off the cross and change your mind?” Her “All right, then, I’ll go to hell” becomes her “I don’t believe in Beatles.”

Baker excels at turning self-mortification into art, but it’s her prerogative as an artist not to have to keep doing it in perpetuity. I’m reminded of someone like Perfume Genius, whose early lo-fi flagellations morphed into glossy art-pop fantasias. As tempting as it is to imagine Baker fully unleashing in one direction or another, the studiously crafted messiness captured here still feels like a compelling next step. Although Little Oblivions describes mainly unhealthy forms of escape, it sounds like something Baker might be embarrassed to admit: true faith in herself..

So, thanks again to my tyrusted adviser, Peter Pearson and to excellent writers like Geoffrey Himes and Mark Hogan for serving as our road map as we follow our art down sidetracks & detours.

The prime sources for this article were found in a work by Geoffrey Himes at Paste on-line and by martk Hogan at Pitchfork, another excellent on-line site. Check out these on-line magazines for scores of similar thought-provoking work.

In our occasional re-postings Sidetracks And Detours are confident that we are not only sharing with our readers excellent articles written by experts but that we are also pointing to informed and informative sites readers will re-visit time and again. Of course, we feel sure our readers will also return to our daily not-for-profit blog knowing that we seek to provide core original material whilst sometimes spotlighting the best pieces from elsewhere, as we engage with new genres and practitioners along all the sidetracks & detours we take.

This article was collated by Norman Warwick, (right) a weekly columnist with Lanzarote Information and owner and editor of this daily blog at Sidetracks And Detours.

Norman has also been a long serving broadcaster, co-presenting the weekly all across the arts programme on Crescent Community Radio for many years with Steve Bewick, and his own show on Sherwood Community Radio. He has been a regular guest on BBC Radio Manchester, BBC Radio Lancashire, BBC Radio Merseyside and BBC Radio Four.

As a published author and poet Norman was a founder member of Lendanear Music, with Colin Lever and Just Poets with Pam McKee, Touchstones Creative Writing Group (for which he was creative writing facilitator for a number of years) with Val Chadwick and all across the arts with Robin Parker.

From Monday to Friday, you will find a daily post here at Sidetracks And Detours and, should you be looking for good reading, over the weekend you can visit our massive but easy to navigate archives of over 500 articles.

e mail logo The purpose of this daily not-for-profit blog is to deliver news, previews, interviews and reviews from all across the arts to die-hard fans and non- traditional audiences around the world. We are therefore always delighted to receive your own articles here at Sidetracks And Detours. So if you have a favourite artist, event, or venue that you would like to tell us more about just drop a Word document attachment to me at normanwarwick55@gmail.com with a couple of appropriate photographs in a zip folder if you wish. Being a not-for-profit organisation we unfortunately cannot pay you but we will always fully attribute any pieces we publish. You therefore might also. like to include a brief autobiography and photograph of yourself in your submission.

We look forward to hearing from you.

Sidetracks And Detours is seeking to join the synergy of organisations that support the arts of whatever genre. We are therefore grateful to all those share information to reach as wide and diverse an audience as possible.

correspondents Michael Higgins

Steve Bewick

Gary Heywood Everett

Steve Cooke

Susana Fondon

Graham Marshall

Peter Pearson

Catherine Smith

Aj The Dj Hendry

Hot Biscuits Jazz Radio www.fc-radio.co.uk

AllMusic https://www.allmusic.com

feedspot https://www.feedspot.com/?_src=folder

Jazz In Reading https://www.jazzinreading.com

Jazziz https://www.jazziz.com

Ribble Valley Jazz & Blues https://rvjazzandblues.co.uk

Rob Adams Music That´s Going Places

Lanzarote Information https://lanzaroteinformation.co.uk

all across the arts www.allacrossthearts.co.uk

Rochdale Music Society rochdalemusicsociety.org

Lendanear www.lendanearmusic

Agenda Cultura Lanzarote

Larry Yaskiel – writer

The Lanzarote Art Gallery https://lanzaroteartgallery.com

Goodreads https://www.goodreads.

groundup music HOME | GroundUP Music

Maverick https://maverick-country.com

Joni Mitchell newsletter

passenger newsletter

paste mail ins

sheku kanneh mason newsletter

songfacts en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SongFacts

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!