Day Two of our Lendanear To Song in-print Festival: LENDANEAR to old songs in new settings.

Day two of our Lendanear To Song in-print Festival

LENDANEAR to old songs in new settings.

by Norman Warwick (with heavy lifting all done by Colin Lever).

Writers who, like my musical colleague Colin Lever, have enjoyed success with traditionally published and marketed books as well as on-line editions and those marketed through the likes of Amazon obviously should take due diligence in verifying the current state of serial fiction and writer Robert Barlow recommends that they follow his link http://topwebfiction.com/?days=10000 to the top user-ranked choices for web-serials over the last several years.

They won´t all be classics, as he says, but they will be typical of the form and will give authors thinking of testing the genre the chance to see how their own work might benefit from following that same route.

Colin´s most recent publication to date is Open Mic, a novel of seeking redemption on the one hand and giving up on dreams on the other.

According to the Amazon synopsis, Hapless Reg is as outdated as the corny motifs on his tee-shirts. Recently retired and at a loose end, he seeks sanctuary from his implacable wife. In the relative calm of the shed, Reg unearths his old guitar. The discovery sets him on a hilarious mission to relive past glories. But the hustle and bustle of OPEN-MIC nights is a far cry from the conservative folk evenings he remembers with such affection. Standing, dry-mouthed, behind a microphone for the first time, he experiences how unpredictable OPEN-MIC nights can be. Rescued by the unflappable Pisspot, the dawning of Anna raises more than just her spirits. Reg’s hopes rest on the prospect of getting his first gig. From pop-up pipers and a tyranny of TV’s to tortured testicles and menopausal magnets, Reg’s road trip is filled with music and mayhem in equal measure. Like a Rom-com in reverse, OPEN-MIC (right) uncovers the vagaries of the Open-Mic music scene. Whether you are a seasoned musician, a happy amateur or a watcher in the wings, Reg’s journey is sure to put a smile on your face´ ´

The late-aged couple at the heart of the novel (and it is, indeed, a novel with heart) seem to feed each other straight lines that the other is invited to finish with dismissive insult. It is, though a story of much more than their angsty squabbling and is, in some ways, about how an artist gets his product to the market place.

That is something Colin and I (performing left as Lendanear) have been trying to do for several decades now, each in our different ways, We spent ten years touring folk clubs writing and fighting and recording four albums. After our duo of Lendanear folded Colin joined up with Steve Roberts in The Renovators and I formed Just Poets with Pam McKee and began writing the all across the arts page in my local paper. It was during this period, of around another ten years, that I shared with Colin a Hugh Moffatt saying that songs are intended for light years of travel, and over time we each came to interpret that in our own way.

To me, at first, the phrase came to seem like an extension of the Roland Barthes theory I was simultaneously enjoying as a mature student at the University Of Leeds. The on-line site, Interesting Reading, seeks to explain the theory thuds:

The Death of the Author’ is an influential 1968 essay by the French literary theorist Roland Barthes. But what does Barthes mean by ‘the death of the author’? This important short essay was crucial in the development of poststructuralist literary theory in the 1970s and 1980s, as many English departments, especially in the United States, adopted Barthes’ ideas (along with those of other thinkers such as Jacques Derrida).

Let’s take a closer look at Barthes’ argument in this essay. You can read ‘The Death of the Author’ before proceeding to our summary and analysis of it.

‘The Death Of The Author’ is an influential 1968 essay by the French literary theorist Roland Barthes. But what does Barthes mean by ‘the death of the author’? This important short essay was crucial in the development of poststructuralist literary theory in the 1970s and 1980s, as many English departments, especially in the United States, adopted Barthes’ ideas (along with those of other thinkers such as Jacques Derrida).

Let’s take a closer look at Barthes’ argument in this essay. You can read ‘The Death of the Author’ here before proceeding to our summary and analysis of it.

Barthes (left) begins ‘The Death of the Author’ with an example, taken from the novel Sarrasine by the French novelist Honore de Balzac. Quoting a passage from the novel, Barthes asks us who ‘speaks’ those words: the hero of the novel, or Balzac himself? If it is Balzac, is he speaking personally or on behalf of all humanity?

Barthes’ point is that we cannot know. Writing, he boldly proclaims, is ‘the destruction of every voice’. Far from being a positive or creative force, writing is, in fact, a negative, a void, where we cannot know with any certainty who is speaking or writing.

Indeed, our obsession with ‘the author’ is a curiously modern phenomenon, which can be traced back to the Renaissance in particular, and the development of the idea of ‘the individual’. And much literary criticism, Barthes points out, is still hung up on this idea of the author as an individual who created a particular work, so we speak of how we can detect Baudelaire the man in the novels of Baudelaire the writer. But this search for a definitive origin or source of the literary text is a wild goose chase, as far as Barthes is concerned.

He points out that some writers, such as the nineteenth-century French poet Stéphane Mallarmé (right) , have sought to remind us, through their works, that it is language which speaks to us, rather than the author. The author should write with a certain impersonality: writing is done by suppressing the author’s personality in order to let the work be written.

Moving away from our traditional idea of ‘the Author’ (Barthes begins to capitalise the word as if to draw a parallel with a higher entity, like God) can help us to see the relationship between writer and text in new ways. In the traditional view, the author is like a parent, who conceives the text rather as a parent conceives a child. The author thus exists before the novel or poem or play, and then creates that literary work.

But in Barthes’ radical new way of viewing the relationship between the two, writer and text are born simultaneously, because whenever we read a literary work we are engaging with the writer here and now, rather than having to go back (to give our own example) four hundred years to consider Shakespeare the Renaissance ‘author’. ‘Shakespeare’, as writer, exists now, in the moment we read his works on the page in the twenty-first century.

Writing is a performative act which only exists at the moment we read the words on the page, because that is the only moment in which those words are actually given meaning – and they are given their meaning by us, who interpret them.

Instead, then, we should think of not ‘the Author’ but ‘the scriptor’ (Barthes used the French scripteur in his original essay, a rare French term which means, essentially, ‘copyist’). We shouldn’t view a work of literature as a kind of secular version of a sacred text, where the ‘Author’ is a God who has imbued the text with a single meaning. Instead, the literary text is a place where many previous works of literature ‘blend and clash’, a host of influences and allusions and quotations. Indeed, ‘none of them’, Barthes asserts, is ‘original’. Instead, the text is ‘a tissue of quotations’.

Barthes concludes ‘The Death of the Author’ by arguing that imposing an Author on a text actually limits that text, because we have to view the literary work in relation to the author who wrote it. Its meaning must be traced back to the person who produced it. But writing, for Barthes, doesn’t work like that: it’s a ‘tissue of signs’ which only have meaning when the reader engages with them. The meaning of a text lies ‘not in its origin but in its destination’, and that in order for the reader of the text to exist and have meaning as a term, we must do away with this idea that the author determines the meaning of the text.

‘The Death of the Author’ makes several bold but important claims about the relationship between author and literary text: that works of literature are not original; and that the meaning of a work of literature cannot be determined simply by looking to the author of that work. Instead, we as readers are constantly working to create the meaning of a text.

Writing is ‘the destruction of every voice’ – not the creation of a voice, which is how we tend to think of a creative art such as writing. The literary text is not original, either: indeed, every text is a ‘tissue of quotations’. This may strike us as Barthes overplaying his hand – surely works of literature contain original thoughts, phrases, and ideas, and aren’t literally just a string of quotations from existing works? – but Barthes is interested in language throughout ‘The Death of the Author’, and it’s true that in every work of literature the words the author uses, those raw materials through which meaning is created, are familiar words, and therefore not original: merely put together in a slightly new way.

(A notable exception is in the nonsense works of Lewis Carroll, whose ‘Jabberwocky’ does contain a whole host of original words; but part of the fun is that we recognise this poem as the exception, ather than the normal way works of literature generate their meaning.)

‘The Death of the Author’ was a bold and influential statement, but its argument had numerous precursors: his emphasis on impersonality, for instance, had already been made almost half a century earlier by T. S. Eliot (right), in his 1919 essay ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, although Eliot still believed in the poet as an important source of the written text. And in the mid-twentieth century, New Criticism, particularly in the United States, argued that the text had meaning in isolation, separate from the author who produced it, and that searching for authorial intention in the work of literature was something of a red herring.

‘The Death of the Author’ makes a compelling argument about the way a work of literature has meaning in relation to its readers rather than its author. We twenty-first-century readers of Dickens are not the same people as the Victorians who read his work when its author was alive, for instance. Words change their meanings over time and take on new resonance.

However, we might counter Barthes’ argument by making a couple of points. The first is perhaps an obvious one: that it needn’t be an ‘either/or’ and that the birth of the reader doesn’t necessarily have to be at the cost of the death of the author. We can read Keats’s poems and try to understand what the young Romantic poet meant by his words, what he was trying to say as the author of the work, while also acknowledging the fact that ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ has new resonances for us, two centuries after it was written.

The second point is that viewing a work of literature as a mere ‘tissue of signs’ threatens to put it on the same level as a bus timetable or a telephone directory. They, too, contain nothing but familiar words, names, and numbers, and are not original. Works of literature may (in the main) draw on familiar words and even familiar phrases, but great works of art put these words and ‘signs’ into new combinations – and there is a virtually infinite number of those – which can create new meanings for us.

So we might view the relationship between author, text, and reader as a tripartite partnership rather than bipartite one: all three elements are important in creating the text’s meaning. If I give a poem to my students and don’t tell them anything about its author, they can analyse the poem’s language and try to determine its meaning; but knowing something about the author and their context may help to reveal new meanings which are important in understanding the text. As soon as we know a poem is by Sylvia Plath, and we can bring the details of her life (and death) to our reading of the poem, its meaning changes.

So we do need to bear in mind who wrote a text and how that might be significant in creating its meaning, even if we also need to acknowledge (as Barthes does) that once a text is written and goes out into the world, it is no longer solely the property of the author who wrote it, but its meaning is also generated by those who read it.

The body of work Colin Lever and I produced in the nineteen seventies and eighties was of around a hundred songs including circa seventy completions, fifty odd recordings, and a collection of thirty or so regularly included in our club performances, that would regularly include (Just) The Way You Look Tonight.

The Way You Look To-night is a song from the film Swing Time that was performed by Fred Astaire and composed by Jerome Kern with lyrics written by Dorothy Fields (left). It won the Academy Award for Best Original Song in 1936. Fields remarked, “The first time Jerry played that melody for me I went out and started to cry. The release absolutely killed me. I couldn’t stop, it was so beautiful.”

In the movie, Astaire sang “The Way You Look To-night” to Ginger Rogers while she was washing her hair in an adjacent room. His recording reached the top of the charts for six weeks in 1936. Other versions that year were by Guy Lombardo and by Teddy Wilson with Billie Holiday.

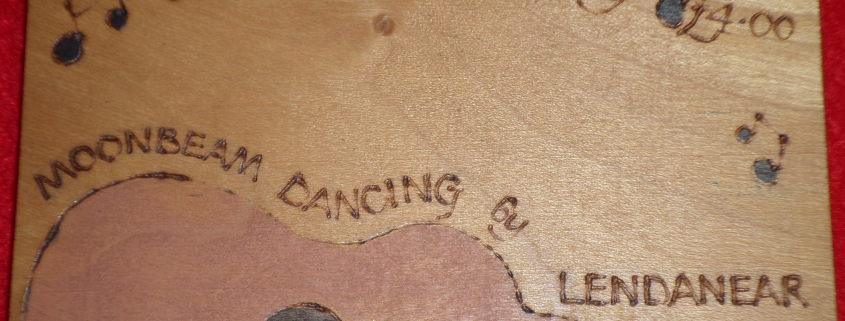

In the Lendanear stage show the song was appended to one of our own poems, Moonbeam Dancer. I ´performed´ the poem whilst dressed in an old fashioned coal mining attire. I addressed the poem in the voice of our fictional character Coal Öle Joe to an invisible Greta Garbo on an imaginary silver screen, with the conceit being that one day Joe reaches out to the screen and Greta steps off the screen to dance with him in the aisles of the cinema. At that stage of the narrative Colin would break in with the song from the dark at the back of the stage and I would reach out, to n unsuspecting lady in the audience (usually a pensioner). The two minute dance to Colin´s rendition would turn a song once sung to Ginger Rogers in a bath to being sung to an old lady in a cinema, which was actually a folk club.

Jerome Kern, who had of course suffered The Death Of The Author on writing the song, would have turned in his grave,

We were certainly not aware of how many times the song had been recorded, or how many miles it had already covered on its light years of travel. We subsequently learned it had been recorded by Billie Holiday, who became a major name in my record collection, as did Peggy Lee who also recorded the song. Frank Sinatra recorded it, too, and so did Bing Crosby with his wife Dixie Lee. The Lettermen enjoyed their first hit with the song, reaching number 13 in the Billboard charts.

There was blues interpretation of the song by Sonny Rollins and a jazz recital of it by Thelonious Monk. Tony Bennett not only recorded a solo classic of the song but also re-recorded The Way You Look Tonight with Faith Hill on his first duets album, and Gloria Estefan recorded it on an album of Standards. Naturally Ella Fitzgerald included it on the recording of The Jerome Kern Songbook.

I´m not actually sure where we first heard the song, but whatever version we first heard certainly didn´t include a coal-miner dancing with Greta Garbo, (left). It goes to show that if songs really do undertake light years of travel they might land anywhere to re-fuel, and we think we heard, or mis-remembered after recording the song that the name Greta Garbo translated in English to ´spirit that dances in moonbeams´.

Lendanear similarly adapted other songs such as Factory by Bruce Springsteen (off his 1978 album Darkness On The Edge Of Town). We turned the song into a short playlet and recorded it on Our Theatre Of The Mind live album, which also included a kidnapping of Digging This Hole a la Lendanear.

Our final album recording was called Songs For Sarah, on which we re-ordered nine of our songs, most of which had been previously recorded, into a chronological soundtrack that told of the real-life murder of a friend of mine, and closed with a dramatized version of Back Street Love by Curved Air.

This was something of a trick we had previously employed on our first album Moonbeam Dancing. The album was pretty much a recording of more or less the only fifteen songs we had recorded at the time, all of which we had written as separate and autonomous. When we decided we wanted the songs to follow the lives so far of we two members of Lendanear, we simply recycled them in a new chronological order. Colin had written Matthews Song for his first born and I had written And Time for my young baby, Andrew, but we put them together as a spoken word melody. We put each song into a linear narrative, without any real effort to honest. They simply fell into place.

Colin similarly re-visited and revised some Lendanear songs on-stage with Steve Roberts in The Renovators, and I managed to join Colin and Steve for a one-off re-union gig.(right)

Before and since that gig I have always treated our catalogue of songs as a never-ending story suitable for whatever narrative I might be working in at any given time, I thought that it should be fair game for me to ´lift´ Lendanear songs to suit my artists in schools duo of Just Poets, and the workshops we delivered. Again; I was just as happy to transpose the works of others and not only of my own. I´m not sure what Stanley Holloway might have made of The Lion And Albert becoming the basis of ´trials´ which saw us electing a jury from a classroom of primary school children to hear the evidence of the monologue and then decide whowas to blame and what should be done.

On other occasions Just Poets would take the Lendanear song Fishes And Coal and use it in a musical playlet that spanned three generations of miners and trawlermen in tracing the premature end of the coal mining industry and the similar plight of the fishing industry in Britain. We used Colin´s wonderful narrative of Fishes And Coal, surrounded it by Working In A Coal Mine (by the brilliant Allen Tousaint) and the afore-mentioned Moonbeam Dancing, featuring Coal ´Ole Joe, Coal Hole Cavalry by Teddy Edwards and closed with a sad, and decidedly sinister Black Kisses by a friend of mine, Kim Prince, who was a poet from Dorset. All this helped us enthuse primary school kids to give us their sensory perceptions of a coal mine and take part in discussions about work-safety, fossil-fuel, climate change, the film industry and fact and fiction and fibs.

I have also adapted my own lyric of Still Chasing That Rhyme into a novel about Guy and Susanna Clark and Townes Van Zandt (left) and scores of other Americana artists and developed it into a novel that also includes the fictional Rex Bob Lowenstein, as created by Mark Germano And The Sluggers. My (yet unpublished in full form) novel then became a selection of songs (self-penned and written by others) called Invisible Angels.

Although I am proud my name is attached to Fishes And Coal, the truth is that it is Colin´s song in its entirety. Nevertheless, he has never worried about where I might take it. I have created a Jeffrey Archer-esque novel around the song´s two central characters in the first half of a story that spans three hundred years and that has (I would say this, of course) ´best seller´ already stamped on the cover. That cover hasn´t been created yet, of course. I´m only half way through the text and so far it has taken me the best part of a decade.

So, it is true that songs are intended for light years of travel and the fact that Colin and I are in our seventies does not mean the songs, when it comes to the practical Death Of The Authors rather than any Barthesian theoretical time, will not just lay down and die.

Lendanear songs will live on long after Warwick & Lever have sung our version of Goodbyee, although that song is itself another example of how songs can be re-contextualised. Good-bye-ee! is a popular song which was written and composed by R. P. Weston and Bert Lee, Performed by music hall stars Florrie Forde, Daisy Wood, and Charles Whittle, it was a hit in 1917.

Weston and Lee got the idea for the song when they saw a group of factory girls calling out saying goodbye to soldiers marching to Victoria station. They were saying the word in the exaggerated way which had been popularised as a catchphrase by comedian Harry Tate.

The song, decades later, then lent its name to “Goodbyeee“, the final episode of the sitcom Blackadder Goes Forth. with its heart-breaking, over the top final scene.

In the past, Colin has written factual books about the educational system in the UK and novels set on his now home island of Jersey

Having recently turned our Lendanear back-catalogue into a web site, at www.lendanearmusic and then into a novel, Colin now tells me he has received funding to turn the novel into an episodic radio sit-com. He is currently at the casting stage.

He also has a bag-full of great songs written in his own name and I am hoping he might drop at least one of them, The Last Priest, because I would love to adapt it into a short story, or actuallñy, it might make a good novel which be perfectly adaptable to a film. It hasn´t actually taken off yet, although Colin has recently recorded it on You Tube and we´re just waiting for Mr. Spielberg to call.

Meanwhile the most recent song we have written together is Para Lara which is really a song about the notion of any poet´s muse, rather than about the girl who is this poet´s muse, Lara Hernandez, (right). It was written almost as a rap but Colin somehow wove it into a melody. He showed it to some classical and Spanish guitar players and they are apparently going to record it with a girl singer,…………………. another song on light years of travel.

So, as ever, a pebble dropped in a puddle of water seems to have sent ripples rolling high and strong enough for a surfer dude to hang a perfect ten.

Of course Perfect Ten was actually the title of a song by Beautiful South who also wrote and recorded Song For Whoever, not so much a song about a poet´s muse, but a song about the poet´s need for a muse.

I understand from Colin that he is thinking of employing a few of our Lendanear songs as incidental music to pass the narrative along from episode to episode. He even e mailed and asked my permission to use them.

I didn´t grant it because I don´t want to earn any money out of all his hard work in turning our songs into a book, into a radio series and eventual Hollywood blockbuster after the likes of Sunshine On Leith ! Like hell, I don´t,….so, permission granted.

Actually I think there are some of our songs that would sit easily in some of the scenes Colin is likely to expand on. No Way To Go On has a lyric about a diminishing law of returns in Lendanear at the time but would certainly describe the disintegration of a marriage and songs like Just Listen Don´t Talk would certainly suit the central female character of Colin´s work though it was written about a classroom environment and it will be exciting to learn which of our works Colin picks up and re-locates.

What I will be far more interested to see, though, is which of our songs might adopt an entirely new meaning to address a situation in the script. That will be truly fascinating.

As Hugh Moffaat told me, songs are intended for light years of travel I hear songs as Invisible Angels, moving from sad to glad to be there whenever we need them. And Colin and I have been surrounded by invisible angels throughout our careers……

Thank you for reading this revisionism on day two of our Lendanear To Song in-print Festival and we hope you will log in again tomorrow to read about why we think of our music as a that series of happy accidents that others call ´the alchemy of creativity´.

Meanwhile Jazz In Reading are pleased to announce that The Foyer Jazz Club at Leighton Park School is back following a hiatus during the pandemic. See poster below for details

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!