RHYTHM AND THE BLUES

RHYTHM AND THE BLUES:

Norman Warwick reads the autobiography of Jerry Wexler

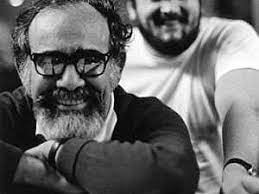

(left) Jerry Wexler’s dedication to his job as one of three guiding hands of Atlantic Records led to his recognition as one of the most aware and fully informed record executives in the record industry today. His affection and respect for artists and their music was mirrored by his special rapport with them and the high esteem in which he was held by these artists.

Jerry is so highly respected as a record producer (Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett (right), Ray Charles, etc.), that the Bill Gavin Poll of disc jockeys across the country have voted him “Record Man of The Year” for two consecutive years: 1967 and 1968. His affability is augmented by his keen business sense and the invaluable, yet indescribable ability to “feel” when a record has that “certain something,” plus a fantastic sense of “timing” (the best example of which is Aretha Franklin’s success on Atlantic).

Atlantic’s artists who were produced by Jerry and often later sought out his opinion on their recordings knowing that he would speak frankly.

“I would always let them have it, exactly what I thought.” This even applies to some artists who are not signed to Atlantic for whom Jerry’s opinion was invaluable. Otis Redding (right) was reportedly seeking to find a way via the Atlantic-Stax/Volt tie-in to have Jerry produce his next sessions at the time of his death last December.

“Above all I dig the Stax operation. I have tried to utilize a lot of their techniques. Our methods here which go back a dozen or 15 years, served us in good stead until the Stax thing came along, and showed us that we were sort of super-annuated. We had the good fortune to form the symbiotic relationship where we could feed on each other. I just think they are fantastic. The reason I picked Stax as my first choice, is because they are the best at the kind of music that I like the most.

Jerry’s most spectacular and consistent recent successes as a producer was perhaps with Aretha Franklin. It was Jerry who selected “I Never Loved A Man” for Aretha to record at Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals, Ala.

Jerry always denied having had any special foresight for Aretha.

“I had heard her sing on records, and I just thought she was fabulous, and I thought it would be nice if I would have the opportunity to record her some day. I had no intimation that she was going to have a string of Number One million-sellers, and she would upset the world. The ballads and blues she sang at Columbia were a little manicured. We just went in and started doing our soul so-called style of recording her.”

Aretha (right) herself credited Jerry’s “timing,” but also credits her success to the fact she and Jerry worked well together. “Aretha and I select all the songs together, spending a lot of time together. I get a song-bag together and she gets a song-bag together, and we sit down and exchange ideas and we just eliminate until we get what we need.”

Jerry joined Atlantic in 1953. He had had some previous music business experience at BMI and Billboard Magazine (“I got a job there reviewing records”), and the offer came to him from Atlantic President Ahmet Ertegun, a friend from the old days of jazz record collecting — “collectors used to run in packs” — packs which also included Ahmet’s brother, Nesuhi (now an Atlantic Vice-President), and Ralph J. Gleason, the noted jazz critic once with Downbeat, who has since helped and written for nearly all the new musical publications since then (currently Rolling Stone).

“We were as many as six partners at one time,” recalled Jerry about the people who were in on the early progress of the small R&B label at various times, “but now we’re down to three. It’s a very happy relationship.”

Jerry credits Ahmet Ertegun (left) in helping him to get his feet wet producing Ray Charles’ first sessions. Ray’s contract was purchased from a small California company, Swingtime, for “the princely sum of $2,000.” Jerry disclaims any influence on Ray’s recordings, stating: “Recording Ray Charles is like putting a meter on fresh air — ain’t nothin’ to it — just open up the pots. It was very instructive.” However, the real key to Ray’s success in Jerry’s eyes was “when he formulated his own permanent band.” When this happened, Ray called Atlantic one day from Atlanta, Ga., suggesting that they come down and record him.

“So we went to a place called the Royal Peacock Club. It was all there: complete, born — mop! There it was — playing ‘I Got A Woman,’ the whole new Ray Charles thing. He had the band sitting there, we walked in, and he said, ‘Okay, count off, 1, 2, 3’ and they started to play all these songs … the full-blown Ray Charles style that we know. There were just barely intimations of this until this point.

“The amazing thing was that we went into a radio studio to make the records; there were no recording studios in Atlanta then. It was real old equipment; a radio engineer; and we had to stop every half hour or so while they gave the news because the control room was where they were broadcasting the news! I remember, it was three hours and we couldn’t get a balance. We didn’t record note one. But we got ‘I Got A Woman,’ ‘Come Back Baby’ and ‘Greenbacks’ on that first session.”

At first glance Jerry looked like a record executive stereotype, with slightly greying black hair, mustache and goatee, and black-rimmed glasses (which he was constantly exchanging, and peering over the top of), but a closer look at his “mod” dress (turtleneck sweater/shirts with his jackets) and his distinct New York accent (Washington Heights) laced with musicians’ slang, and there was no mistaking that the man you were talking to was the head of Atlantic’s A&R.

Jerry’s always busy schedule was never quite so busy that he couldn´t find time to observe, comment on and sometimes bitch about various music industry sidelines. One was the “Rhythm and Blues” category of the NARAS (National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences) Grammy Awards. He felt that they were simply misguided about selections to be voted on:

“The Grammy tastemakers — they voted certain artists in, who happen to be black artists, who have nothing to do with Rhythm and Blues; I don’t want to mention any names, but there’s been some tragic miscarriages of justice. I’m not pleading my case: I think it would be very fair if James Brown would win the award quite often, as well as a Wilson Pickett, a Joe Tex or an Otis Redding.”

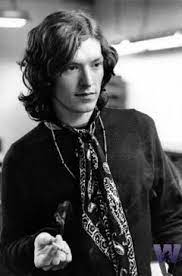

Having worked so closely with black artists, Jerry had very pronounced opinions on the relation of soul music and rock, and the controversy about whether any white musician can sing real blues:

“It’s a very simple controversy: Stevie Winwood — period. The only person who seems to exhibit that quality for real is Stevie Winwood. I think the problem is the critics, the young rock critics of today who rather exemplify the taste of the young teeny — boppers for whom they’re writing, and who are more concerned with the cultural trappings and the attitudinizing of these people than with the music. There was an article in The New Republic with the headline ‘Eyes of Blue, Ears of Tin.’

“Somehow there has been a body of alleged reviewing in which a lot of youngsters become intoxicated with the sound of their own prose. And in which there is very little to do with the music. In the same way that Jimi Hendrix has no need to poke the neck of his guitar through an amplifier, these people — ’cause Jimi Hendrix has something very real to offer musically — these people, are seduced, their eye is taken off the ball. They’re led away from the nitty gritty, and they never do get tuned into the music. Therefore I would like to know by what right these “eyes of blue, ears of tin” have the right to criticize or cannonize, or fault or praise anybody from Mike Bloomfield to Eric Clapton on to Albert King? Some of them admitted to me they can’t even hear the music. They haven’t heard it. They haven’t been prepared for it, either in life exposure or musical exposure, and the whole thing becomes a big, bloody fraud.

“One of my pet peeves is this noxious hippy use of this word ‘Spade.’ It’s just disgusting to me the way they cavalierly throw it around in print in EVO, in the Village Voice, and there’s some, there are a lot of people who are guilty who should know better. I don’t think that this word is sanctified, accepted or condoned by any Negro people, I think that our friends are working under some sort of misconception here, and I think a strong effort should be made to get it at least out of the prints, to get it out of the mouths of the critics and writers for the ‘underground newspapers,’ and it’s a noxious term, as bad as that other bad word, as far as I’m concerned. The thing that angers me, is the certitude and the self-righteousness with which the hippies use it, as though they’re privy to some esoteric knowledge of which the square world doesn’t know about. Well, it’s square as could be, which is the case with so many of the things about the hippies. It’s a manifestation of their crashing squareness.”

Although Jerry led a super-hectic life at the office — phone constantly ringing; conference with artists as well as with his partners; auditions, and all the other chores of a music executive — his attention to what might be considered the smallest detail paid off in countless ways. His family willingly came to accept the fact that his day didn’t necessarily end at the office since his home telephone number is listed in the phone book in case any artists, disc jockeys or music business associates might not have been able to catch up with him at the office.

He somehow, though, found time to write an autobiography, published in 1993

When Larry Yaskiel (left) gave me a gift of that biography only this year, I accepted it eagerly, never having read it, but I was pretty familiar with the story. Music journalist and promoter, mingles with the stars and forms record label and produces huge hits. What I couldn´t have guessed at was the pace, the energy and the eloquence of the street language Wexler twists into echoes of Milton and Marley and Wordsworth and Stevie Wonder.

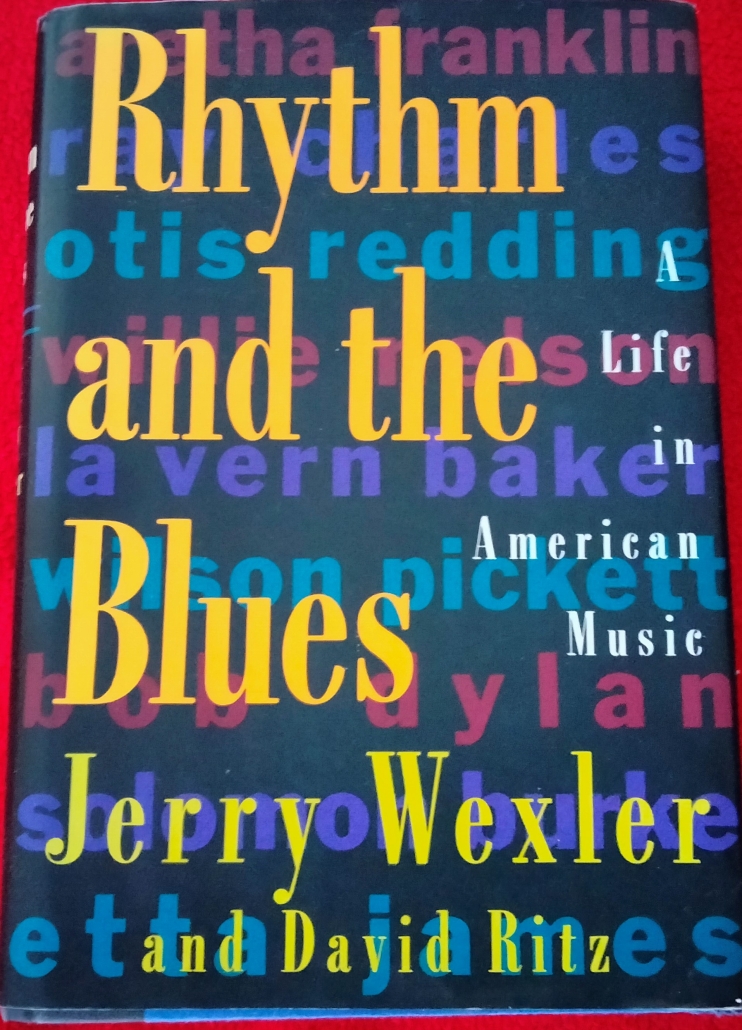

The biography Rhythm And The Blues, a life in American music tells all the details of the above but, obviously in Jerry´s own words,…. and what words they are; dancing across his pages, they jive and they strut and they stroll with eloquent nonchalance as he makes his points. Its sub-title of A Life In American Music might have us contemplate whether it is referring to the genre of rhythm and blues (a term first coined by Jerry Wexler) or to Wexler´s own ´life in American music.´

The book, still in print and available through sources like Amazon was first published in 1993 and David Ritz is credited as co-author, but the phraseology that makes it such a joy would seem to be all Wexler´s.

His account of how he talked his way into co-ownership of Atlantic Records and went on to produce some of the century’s great pop music all makes for some of the juiciest music history one could hope to find. As an insider’s account of the golden age of rhythm and blues, this memoir may be matched only by Atlantic founder Ahmet Ertegun’s—if he chooses to write one.

By turns regretful and boastful, Wexler offers a story that is above all a superlative read, with the sections describing his 1920’s-30’s Manhattan childhood as interesting as the more musically oriented later chapters. With help from Ritz (who’s written bios of Smokey Robinson and Marvin Gaye), Wexler describes his years at Billboard magazine, his move to Atlantic, and his relationships with the Chess brothers, Alan Freed, Phil Spector, and many others.

Colourfully colloquial and unflaggingly enthusiastic, Wexler made important connections between various styles and artists—noting the influence of the blues, for example, on country balladeers—and showings what a complex cultural phenomenon the best pop has always been. Accounts of how he managed recording sessions with everyone from Ray Charles to Aretha Franklin to Bob Dylan reveal much about both music history and making. Although testimony from ex-wives, friends, and (surprisingly) enemies isn’t always well integrated, and though some readers will be less sympathetic to the author’s temper and excesses, Wexler’s contribution to the music is unquestionable, and there’s plenty of material here that only he could provide. Many anecdotes—including an amazing account of a recording date with Guitar Slim (right) —may pass into legend.

For scholars and R&B/pop aficianodos, a terrific read—in spite of and because of its idiosyncracies—and great fun for others as well. (Seventy-five photographs—not seen). The book was first serialised in Rolling Stone which might or might, perhaps not surprisingly, reflect a mutual admiration between Wexler, and his preferred genre of music, and the magazine which still serves all genres with reverence.

At least one reviewer of the autobiography felt it was rather a pity that no accompanying cd was recorded to slip inside the front cover to showcase many of the names referenced in the book.

There was a similar move when Dylan released his book of lyrics, but there still remains too little synergy shared beteen print and audio publishers.

Let´s see if we can rectify that. Here at Sidetracks and Detours we are always happy to suggest a track listing to accompany an article on our pages. I think we have included a dozen or so over the last three years., but we leave it to our readers to accumulate the tracks for themslevesd and make their own recording. However we are exploring how we create a sustainable part of our operation that might be able to produce Sidetracks & Detours cds.

For now, though, here is our recommended playlist.

Sidetracks & Detours

RHYTHM AND THE BLUES

in memory of Jerry Wexler

I Never Loved A Man

Aretha Franklin

Wait Till The Midnight Hour

Wilson Picket

I Can´t Stop Loving You

Ray Charles

Sir Duke

Stevie Wonder

I Got A Woman

Ray Charles

I Feel Good

James Brown

Ain´t Gonna Bump No More

Joe Tex

The Tears Of a Clown

Smokey Robinson

Slow Train Comin´

Bob Dylan

Sitting On The Dock Of The Bay

Otis Redding

Guitar Slim

Sitting On The Dock Of The Bay

Otis Redding

Higher Love

Steview Winwood

Along About Midnight

Guitar Slim

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!