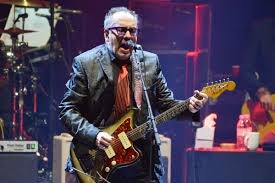

ELVIS COSTELLO: seeing himself as a songwriter

ELVIS COSTELLO: seeing himself as a songwriter.

Norman Warwick reads his freakonomics interview

So explain what you mean when you say you had reached the point in your career when were almost sure you were a songwriter. Do you mean a song-writer for other people?

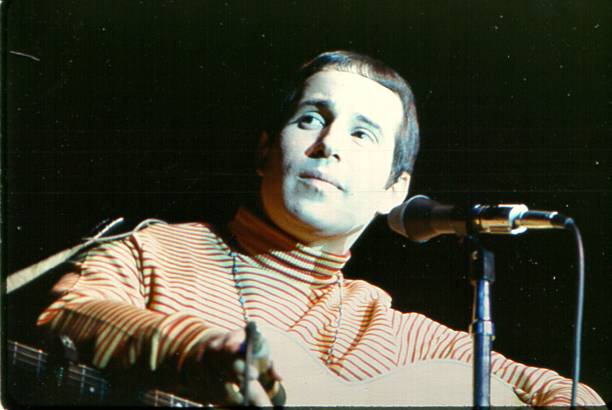

Well, by then, I’d got possessed of the idea. I’d watched too many Hollywood movies where somebody burst into a room to go, “I’ve got a song for you” and make them listen to it. And I did do that for a few years when I returned to London in 1973. I was playing my songs still around, wherever they let me play, which were the remnants of the English folk club scene where Bob Dylan and Paul Simon (left) had made the first steps in the early 60’s. It was only 10 years, 12 years later that it was quite changed, the scene. We’d had all of the late 60’s psychedelia. The music that was in the pop charts wasn’t really yet quite disco, but it was like dance music and glitter.

And the acoustic music, which I really loved was mostly played by Californians, or people that came out of California: James Taylor; Joni Mitchell, although she was Canadian was seen as Californian; Crosby, Stills and Nash; and that kind of music. It seemed quite remote, somehow glamorous. And you never thought you would see those people. And there were lots of really good musicians playing around you could see and I’d run across them. But we didn’t hold them in the same regard as the American musicians.

And that’s always been the way the English think. Whether it would be jazz, or rock and roll, or even acoustic music. So I would go to publishing houses and try and get them to listen to my songs and I think of them now they were not at all suited to other people.

I would go with a reel-to-reel tape, I’d made in the bedroom and and I´d take my guitar, and I’d make them listen to the songs, which they would take calls in the middle of the songs, and it was pretty not good for the confidence — or maybe very good for the confidence, because I got a little tougher. And I got a few paying gigs playing my own songs. I abbreviated my name to my initials. My dad always called me D.P. so I adopted that. Then, I adopted my Irish great-grandmother’s name Costello; but everybody said it like an Italian name. I let them think that I was Italian. Not that anybody really cared, but it looked better on a bill? And then I became the resident singer in a club where quite good people came and played.

The ´Elvis´ didn´t come in Not until I took a tape to my first record company Stiff, which was a little company that started with like a thousand bucks, maybe not even that, borrowed money, and started putting out singles in 1976. My producer, one of my favorite singers, Nick Lowe, was their first artist, and I was the first person to knock on the door with a demo tape. And at first, they they had me record a couple of songs, but very much with the view of somebody else singing them. They were still seen as demos, they weren’t seen as releases.

. Stiff weren’t sure that I wasn’t a writer for somebody else. That was really the objective. My managers were managing Nick Lowe and Dave Edmunds‘ band, Rockpile (right) ; and Dave didn’t write. So, they tried to sell Dave on a couple of my songs and they tried to give them to other people

And people found them too quirky, so that, in the end, they suggested first putting half a record out with another songwriter, like Chuck Meets Bo. There’s a jazz record with one side of Chuck Berry, one side of Bo Diddley on it. And thankfully, I just ended up writing so many songs that there were 12 and they put that out. I was still working in an office till the week before my record came out.

This was at Elizabeth Arden?

Yeah, I was a computer operator. I’d sit in a little air-conditioned cubicle and pretend I knew what was happening with the computer and write my songs in a book. And sometimes if I had to work at night, an evening shift, it was just one operator — it was only an I.B.M. 360, it wasn’t a complex computer. It was probably not as powerful as your phone, and I just wrote my songs in the evenings, and I was still working there. I had singles out, and I was still working there.

Let me ask you an existentially depressing question, which is for every one of you, Elvis Costello, or Declan MacManus, working that job and writing songs, for every hundred thousand of you, there’s one who actually gets to do what you did. And there are questions of talent versus hard work and opportunity and luck and so on. What do you say to all those people out there who have some kind of dream of being a creative? And many people are realistic, they don’t expect to reach huge success, or even do it as their livelihood even partially. But, do you discourage those people from hanging onto that?

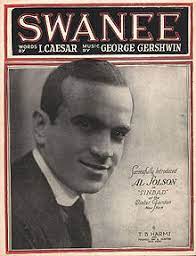

Right now, it would seem to be tougher to start, because I am beginning to think there was a narrow window of opportunity which I caught the last few years of, where it was possible to make a reasonable amount of money from making records and having a musical career, other than to just fund the next go around on the machine. Obviously, before that, people bought the rights to songs; they sometimes put the names of the publisher or the singer on to the song. That’s how you come to see songs that are credited to Al Jolson (left) or Elvis Presley or Frank Sinatra, who to my knowledge never wrote anything.

And of course latterly — and when I say I latterly, it’s almost 25 years now — there’s been a shift to the ownership of all of the medium through which music and most other entertainments appear. And it’s transformed the sense of ownership. On the one hand, the delivery of those things has become a commodity owned usually by super-corporations who are not in the same business as I’m in. In other words, say, Universal Records, who hold the rights, for the time being, to my catalog, are owned in turn by a French utilities company. They run trains, sewage works. They’re not really in the music business, are they? They’re not in the art business, for sure. So, they are the people to whom, the bosses who are above the people who hire me to work, make records. That’s who they are. Now independent companies, like the one I’m recording for now, still have relationships because you have to get the physical records out somewhere. And those people control the distribution networks.

But of course, as it’s become a matter of instantaneous access, we’re moving to a model now where nobody really has any physical records anymore, or at least, as generations of people who have no knowledge of that, they have no expectation of owning a physical copy of a record, unless it’s a fetish object like a vinyl record that they bought in a hipster store. They can access something much more readily on the Internet, whether through YouTube or Spotify or such a system. So why would they want to clutter up the house with a bunch of records? There are people that will contradict that. But that is a big model now for it.

So why can’t you have all of those systems, rather than sitting around whining about it. Why not just say, “Well, that’s happened.” You can say there are some things that are unfair or possibly even dishonest about it, but so it’s always been the way that people will say, “Yeah, you can make that record for me, I’ll give you a Cadillac,” and then they would go make millions off that title and the guy would just be driving around until the wheels fell off the Cadillac.

The artists have always had a difficult, hard time getting — In their more egotistical moments, some of the megalomaniac moments they probably believe that they’ve been cheated in some way of a fate, but maybe they just didn’t work hard enough. One thing that really affects some people is that they’re too hip towork. I know a lot of people that that think of themselves as very groovy, that disdain major popular music.

You know who I like? I like Bing Crosby (right) . He was a huge-selling artist. I don’t dislike pop music and actually what music I don’t care for is boring rock music that’s so pompous. I like rock-and-roll a lot, but I don’t hear the thrill in this square music. And each type of music gets infected by that kind of squareness or self-satisfaction or self-fulfilling prophecy that happens in every form of music. And somebody else will tell you that happened to me because they they judge it that way.

Where did your tremolo come from ? Is that what it’s called? Tremolo, vibrato in your voice, when you sing. Did you always do that? Was it a conscious thing?

It’s about three different factors. One is that I was aware of that way of singing. My dad definitely listened to Billy Eckstine. My dad, on some records that he made — he doesn’t have a lot of records under his own name — but the few where he sings in his true voice, oddly enough, you can hear elements of Eckstine in his vocal delivery. And he’s one of my mother’s favourite singers, along with Tony Bennett. And ballad singers tended to use vibrato. The vibrato that might have been inherent in my voice, I think wasn’t so obvious because there were so many words in my songs, there were not many long held notes in the early songs, they mostly very quick fire. And when I slowed the pace down to sing ballads, then it became more apparent — and also simultaneously to that, I have to credit Chrissie Hynde with reintroducing the warm vibrato idea into pop, popular music of the then time. I’m talking about ’80 to ’83, that period after she made her appearance about ’79, ’80, and it reminded me of the sounds that I loved about Dusty Springfield — who was probably my favorite singer, at that time. I think beyond that there’s a certain amount of vibrato as a product of maybe a physiology.

Yeah, and I think also that part of it is physiological. I guess it’s a flaw, in my breathing that the whole engine works like that, and it’s like, if you live with something like a heart murmur it can be like that.

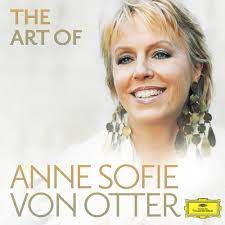

I hear, really, beauty in a lot of the opera singers. I mean, there’s times when you go and it isn’t good. But I know the physical dedication that goes into that. And if you listen to Chaliapin, or Hans Hotter, or Fischer-Dieskau, or any of the great recorded singers — and then there’s the people I’ve seen, my friend Anne Sofie von Otter (left) . I was a fan of hers from the, from just going to the concert hall to always hear her sing, and then we became friends and we made a record together. And she wanted to make a record where she let go of some of the training of her voice, but she’s incapable of signing an ugly note. And of course some of the things that are proposed in the singing of a popular song are sounds that are an anathema to a trained singer. So, it’s quite difficult for them to unlearn some of their training and to be unbuttoned enough to do it.

Do you still have the scream? Do you still scream, ever?

I’m not going to try it now, but I mean, yeah, it’s not something I was conscious of doing. It’s not really a thing, “I’d better put a scream in there.” It’s just something you do. It’s a harmonic. I’m thinking particularly in terms of the beginning of “Man Out of Time,” that sounds like an alto saxophone playing harmonics. It’s not. It’s actually more than one note. And I like that. When it came out, it all went squirrely and I love those things.

I mean, there’s different singers whose techniques I’m fascinated by. I used to love Bobby “Blue” Bland. He used to sound like he was clearing his throat. And Al Green has a — and these are singers that have so much voice, compared with me. I like singers who are kind of tryers, like Rick Danko, who sounded like there’s was a kind of nervous thing to the way he sang that I really loved, and it felt very human. There’s something very beautiful about that, and that’s probably why we’re able to respond to music in other languages without understanding what’s being sung.

We’re maybe fascinated by where the emphasis lies in the kind of music that uses either a different rhythm or a different scale. So it’s always surprising us and the timbre of the voice, as — you cantell, there’s a yearning in it, or a sense of joy, or a sense of lament. I can listen to religious music in the same way without necessarily believing the same thing that the singer is. I can listen to gospel music or cantors, or whatever recordings. It’s just what the singer believes in.

photo 6 Joe Loss (right) was Jewish, I assume. There was a line in your book about how he wanted your dad to have been Jewish.

He was absolutely convinced that my dad was, but I honestly don´t know. I actually don’t know because — I think it’s a bit unlikely, but of course — because of the background of the family. Who knows? I mean, we can’t get back very far with records with Irish people. My great grandfather was what would be called now an economic migrant. He left in the generation after the famine, and unlike a lot of people, he didn’t go to America; he just went to Merseyside. And so I have no idea. If he hadn’t have died in a relatively avoidable industrial accident, I might not even be sitting here talking to you, because maybe I’d be digging a ditch, or loading coal onto a ship, because that’s what he did. And the only reason that the occupation of musician appears in my family is because my grandfather was placed in an orphanage and from there became, joined the British Army when he was 12 as a boy soldier, as a bandsman. And that chance event seems to have derailed our family into a line of work in music. I’ve no way of knowing whether it would have been any different.

I never, oddly enough, it sounds really strange, but I didn’t have any other ambition than just to do this. Including, I didn’t imagine any of the things that happened to me because they were all, from the making of the first record to right now, just the thing that happened next.

Of course, I feel enormously grateful for that.. Even though, in many ways I could have had much more conventional form of success, but I’ve watched friends of mine who are much better known become confined by their success and to the expectationsof an audience, and not being able to outdistance their own shadow, and things like that. So, it seems like a life you’d want. The grass is always greener. I have managed to kind of stay ahead of the wolf by basically working most of the days since I was 17.

And most people would regard me as very, very fortunate, but I’m sure a lot of people that imagine I’m wealthy beyond all dreams. I’m really not. I work to maintain, to look after the people that I want to look out for, for as long as I can do that, and to do the next thing. Quite often the money that comes in to make a record funds that project, like being an independent filmmaker. It’s not about, it’s not about hitting some imaginary number or moving yourself to some other echelon. I’ve never ever thought that, I mean — I think five minutes in the late 70s, we had dreams of breaking America, or cracking America. That was the thing. But when you get there, you sense the vastness of it.

It is crazy, but here’s my question for you, really. The creative part, I want to know: do you feel that your work is an exercise in creativity, and you carve out time and place and mood in which to be creative, or is it work for you?

I don’t really think in terms of definition like a name tag, but if you actually asked me the difference, I say I was a worker of a kind. I work at what I do. And then there might be moments of inspiration that visit you unexpectedly.

Any song arriving is a mysterious sort of thing. I mean it can range from carrying around a phrase in a notebook for four years before it joins up with some other thoughts, or a line of melody that seems to bring it to life and allows you to kind of to represent something that you want to share with people. Or a song can just appear, the whole thing, the words and music. Time stops and —perhaps that doesn´t happen quite as frequently when working on collaboarations. Then, obviously, you’re making a statement and waiting for somebody else’s reply. So it’s like writing away for something.

The instrumentation, that’s a different thing. The instrumentation and the orchestration of the songs was more like, were very complete to me, when the songs were finished. The minute I decided that we were going to do them as a band, then I also started to think.

And I was hearing everything, the vocal and the background voices, the vocal arrangements, the string arrangements, the horn arrangements, they were all to my mind almost extensions of the composition. So as we arranged the parts, I wanted the — I wanted — the whole point of the exercise was to trust in my cohorts. We had gone out last year and looked at the songs from the album “Imperial Bedroom” which, the original band we played it, The Attractions — two of whom played in The Imposters — we truthfully never had the patience to play many of those songs well.

The ones that survived into our live repertoire were songs that were easily adapted to the way we more commonly played, which was more frenetic, and the other songs which were quite detailed in the studio, we didn’t have the patience for the little details and nuances — nor do we have the voices. Nobody could sing in that band except me. So, we never had any vocal harmony onstage for the last 15 years or whatever it is. Davy Faragher has been in the band, his bass playing, a singer, a singing bass player. So we’ve had two-part harmony, but we’ve also started to incorporate two other singers in our live, so Kitten Kuroi and Briana Lee in this case, and on some songs, Davey’s elder brother Tommy.

Davey being a very good vocal arranger in his own right, although I sketched out all the parts in my demos, we would, Davey and I, would then discuss what combination of voice is best used, just the same way as I didn’t arrange every song for the same configuration of instruments. There’s a bassoon on one song, there’s a woodwind quintet where you might have expected to hear a string quartet, you could imagine them playing the sameparts on paper, but I wanted the sense of something breathing, which the wind instruments brought.

I was hearing all of that in my head and then it’s just something that I’ve learnt over the years which is — whereas I used to, whenever I had something outside of the regular instruments of the band, I had to trust somebody to write it down. Sometimes, it would get a little changed, or something would get lost in the translation, and in the early nineties, I learned how to write music down.

I mean I grew up knowing what music was, and reading it but I never had any need to write it down, because the songs I started out with. in some ways they would have been attenuated by writing them down. You had to feel them. But these songs — it was all the process of pairing down the arrangements to the essentials and the rhythm section. And Steve Nieve, who’s been my cohort for nearly 40 years, I mean, he’s a remarkable musician. I mean, he was a 19-year-old Royal College of Music student. So his education was obviously not complete there, but what he brought to the band, and then what he’s developed in all of the music, not just playing with me, but his own compositions. I mean, he wrote an opera. I mean he’s explored things, and piano records, where he’s followed his own instincts about music. He’s the kind of person who can give you lots of invention to any theme you gave him, but also you have to have some discretion about which part of what he’s playing is really magical and which complements the song and which —

I think we worked — I think there are some times when I’ve just been inclined to let Steve go, and when I think about it later maybe I could have been more discerning, but it was so thrilling to hear him play I didn’t do that. So I’m not going to retrospectively re-edit the records. Nearly all of the credit for the production should go to Sebastian Krys. He recorded it. He was the one that made sure the order was kept to things. He got the beauty of the sound. He mixed it. My contribution to the production was really in the editorial of the music, in that I had to be the discerning voice of anything there; I’d say to Pete, “Play a simpler fill,” or “give me something different there if you can.” “Steve, leave this hole because there’s going to be strings there and then you’ll play together the next time,” I mean, he couldn’t know that, because I hadn’t told him.

Well, in some cases we would get in and he’d start to play, and I’d say, “We maybe need to leave more of a hole there,” or “Don’t do that variation because it’s not agreeing with what else is coming.” Because we did do everything separately. Most records I’ve done in the past, 90 percent of them are being arranged from the voice outwards. So, I would sing on a live take and often that would be the take. So, that was a lot of pressure for the band, in that if I got something I liked, they would have to live sometimes with a flawed performance, if you couldn’t fix it in some way. In this case, I didn’t want to do that. I wanted everything to be — that we would agree what we were going to play and we would draw on everybody’s strengths independently.

What was that experience like for you then, as a singer?

That’s really like getting my dream to be Dusty Springfield (left) of going in. If you see those old pictures of where they had the band in the studio and the vocalist in the booth, that’s what it felt like. Because usually, when you’re singing in the studio, you’re imagining, “I’m going to add some stuff to this.” And sometimes when you re-sing a song, it’s because the weight of the original performance wasn’t quite right. There’s nothing the matter with the singing, but maybe it was too aggressive, or not aggressive enough, or not forceful enough, and then when you add those other instruments, the vocal sounds muted. In this case, I had everything to support me. It was like being on stage with an orchestra or an ensemble behind you.

I mean, I don’t mean to be a shrink here. But to some degree, was it — your father died a while back?

No, the people said that when I worked with Burt Bacharach, because I wore a tuxedo, but they’d never seen my dad in a caftan. You know what I mean? It was never psychological. I’m not given to that kind of thing. I mean, I just enjoy doing it this way. But equally, when I invited Burt Bacharach to play with the band we had written about 25 songs over the last 12 years for two musical projects, one of which was based on our original album “Painted From Memory.”

It’s quite difficult to thread a story through a group of existing songs, unless it’s a biographical show about the songwriter or the artist, and therefore we ended up with another 10 or so songs written for “Painted From Memory,” but they were also very slow and melancholic like the original collection which, I guess, scared the producers that we were engaged with, and the show seemed to stall. And after a couple of years of no further movement, I asked Burt two years ago if he would consent to let me bring them out into the light, or the ones that I felt I could sing, because I just thought they were too good. I mean it was absolutely crazy, for good songs — in the case of the two that he leads, they were all his music and I’m only the lyricist.

photo 8 One of the most amazing things to me, and wonderful things, is that Burt entered into a different kind of collaboration 25 years ago than he’d ever had, and he continued to return to that style of collaboration with me. Actually, I think uniquely, I don’t think he’s co-written music with anybody else but maybe Neil Diamond (right) . So, that’s pretty good company to be in. Neil, who has written tremendous songs as well. But Burt was open to a different form of collaboration, a dialogue in music. Why would he need to do that? He’s Burt Bacharach. But that just shows the curiosity.

It has always been the beauty of this collaboration that on the one hand, you had somebody who was open to something different, despite all the experience, despite all of his achievements. And the second thing is, you can’t get anything past him because he hears everything.

What was the song you said you sent to him and he said, “Nope, it’s done.”

Stripping Paper. Because that was also written with a view to being in this musical production. But I’m pretty shrewd about these things, because I’ve read all my musical Broadway biographies, and I know how many great songs have been in and out of shows that’ve been cut.

The Gershwin song you wrote that was in three shows.

The Man I Love. Yeah, unbelievably, in three shows and I think lots of Rodgers and Hart songs went the same way. So, much better songs than I’ll ever write are being cut out of shows, so I make no apology for being tricky enough to make sure that the song stands up on its own, because I don’t really care for songs even in opera where they go, “I’m walking up the stairs, I’m walking down the stairs, it’s a lovely day today.” I don’t care about that stuff, I want to hear about the feelings, or something to do with the story that’s unique. And obviously, these songs that we ended up with quite a few of them are about how we decode the way people look at each other.

“Don’t Look Now,” the second song on the record, is a woman looking at a man saying, “I see you looking at me,” and trying to imagine what is contained within the gaze. She’s trying to see what’s contained within that man’s gaze: Is it admiration? Is it appreciation? Is it lust? Is it ill intent? Another song that Burt wrote the music for “Photographs Can Lie,” the story of a daughter realizing, upon discovering her father’s infidelity, he falls from a pedestal on which she’s placed him. That seemed to be the way these particular songs worked out. They weren’t the last 12 things that happened to me. Maybe that’s something to do with — Well, obviously, it’s something to do with the fact that originally they had a theatrical origin, but even contained within the two or three, four minutes of the song, I just didn’t have the feeling of wanting to be selfish and them being my direct experience, rather than the things that I knew to be true, and things I’d observed, the kind of reactions people had to a discovery.

The song, “Stripping Paper,” that I mentioned a moment ago, is the words of a woman who’s discovered her husband’s infidelity and absent-mindedly almost pulls a layer of wallpaper from the wall; and it’s just peeling off, and she peels it back and behind it is a simpler pattern that is a symbol of when they had less money, and beneath that another even simpler one that may have been on the wall when they first got that apartment, and where they had drawn a pencil mark for their daughter’s, to measure their daughter’s height. When you describe it, it sounds a little sentimental, but when you sing it, it doesn’t read as sentimental because the idea of somebody having almost, like, this book of their life and including, like, joyful erotic memories that she’s wrestling with. I don’t think that, that’s not something that anybody is going to have any problem understanding. It’s not opaque. And the lyrics are pretty to the point on this record, with the possible exception of the first song on the record, which is in itself a sequel.

Under Lime?

Yeah, I mean I took the character Jimmy, from my song “Jimmy Standing in the Rain” which I wrote — well, it was released on a record in 2010. And Jimmy was a portrait of a vaudeville singer, or musical singer in the north of England, who was traipsing round doing this kind of — trying to sell cowboy songs to. That would be the worst time in life to try to do that. And I pictured him kind of beaten down, alcoholic, could have TB; he’s got the full challenge. He finds some comfort in the arms of a woman who in the throes of passion calls out the name of another man. I mean, nothing about his life is encouraging, and he feels himself abandoned.

And then I just left him there at the end of the song and, I don’t know, started thinking about what if he were discovered and kind of disinterred and brought into the realm of light entertainment in England in the 50s? It’s only 20 years later. We think of these eras as totally independent, but of course they’re not. Now he’s on one of those shows where they used to blindfold people and make them guess people’s occupation or identity, and he’s put in the charge of a young woman who is the production assistant of the show, and they tell her, don’t tell him your name don’t let him, whatever you think, don’t let him drink, because he’sdisreputable and he might potentially be going to hit on her when they get alone.

And when they do get alone, he is charming and he starts to ask her all about herself and about her boyfriend and about her family. And then you see how he’s maybe making, a trap and she almost leans into it and she finds him — you can see he’s a ruin but people are fascinated by ruins sometimes, even when they know they shouldn’t be.

And then there’s the line, “I can’t believe this is happening to me.” What is that ?

Maybe she’s flattered momentarily by his attention, and in that little indecision is the risk. But I tried to make it so that I wasn’t judging her or judging him even. He’s obviously not right. In the last verse, it says he shuttered his eyes, that he made a very conscious effort not to look at her. And he thought of a drummer and considered a snare, because he’s laid this trap before, and he may have even taken advantage of that situation before.

Well, I’ll leave it to the listener to decide whether — He says, “you don’t get a record if you never get caught.” And it’s a scene. It’s a scene that isn’t exactly a new one. It’s not made up last week. And it’s been there, it’s been a scene I’ve seen, I’ve witnessed. I just thought that was where we’d leave him. I don’t know whether Jimmy’ll ever make another appearance now. Maybe, maybe in a stripe-y suit. I don’t know. Yeah, I mean that’s the terrible thing about it.

Plainly you read and listen to a lot of music and you have a family and so on.

That’s really enough, isn’t it? I like to see my friends. I keep in touch with people. Life is full and between the people that you care for and as people get older and more vulnerable in your family, you have to spend time with them because that time becomes more precious. I don’t feel that I’m oppressed by anything, really. I’m curious about things. I’ve never reallythought of myself as being cynical. I don’tlike when I see the word “cynical” attached to me, I think I’m very skeptical.

I think you’re right to be skeptical about institutions and the things you mentioned and systems of control, but whether they’re the small ones between two people or the larger ones that are governments or corporations, I just laugh at the idea that people tell you, people in my line of work shouldn’t make a comment, particularly when the comments are not unsubtle slogans. I try, even in, say it’s, “Under Lime,” it’s got three or four points of view within the song. It’s written so the music opens with a strong rhythm and then becomes, as it becomes, there’s more doubt in the motivation of what’s being said, the music changes, and then it explodes into a more celebratory type of music which I suppose has a meaning in that the show does go on despite all of this, and often the scene in the backstage is something we draw a veil over sometime, or we used to draw a veil over.

That’s the same with everything. I mean, problems thatI thought would have gone away a long time ago are still there. Everybody sang that song, and it didn’t change. So you’ve got to keep trying. Some people are in a lifelong service to a better way to live. And some people are just jesters. And I guess I’m one of them.

Well, I gather that doing this, sitting down and talking about yourself is not what you do for fun. But I very much appreciate it.

Your questions are not any pain to me to answer. I hope there’s been something of worth.

Thanks to Elvis Costello for taking the time to speak with us; thanks also to Mark Satlof for making it happen. If you haven’t already done so, check out our “How to Be Creative” series, episodes 354 and 355. It features other creative types like Ai Weiwei, Jennifer Egan, Wynton Marsalis, James Dyson, Rosanne Cash, and Maira Kalman.

Freakonomics Radio is produced by Stitcher and Dubner Productions. This episode was produced by Matt Frassica, with help from Alison Craiglow, Greg Rippin, and Rebecca Lee Douglas. Our staff also includes Alvin Melathe, Harry Huggins, and Zack Lapinski. The music you hear throughout the episode was composed by Luis Guerra. You can subscribe to Freakonomics Radio on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts.

The above interview offers such an insight into the mind (and the heart) of Elvis Costello that a response he made in the summer of 2021, when seemingly defending Olivia Rodrigo (right) who had been accused by plagiarising one of his songs.

CNN reported at the time at what was becoming a pretty chilly summer for Rodrigo. The teenage star came in for criticism from Courtney Love, the Grand Dame of grunge, who called her “rude” for imitating Hole’s album cover. Then social media users accused herof plagiarizing a song by the veteran British artist Elvis Costello.

Fortunately, however, Costello proved to be far more forgiving — and even encouraging — about the similarity between his music and the latest offering from Rodrigo.

After reading an article about Love’s angry accusation, a British teenager called Billy Edwards took to Twitter to remark: “First song on Rodrigo´s album is a pretty much direct lift from Elvis Costello.”

Costello suggested his own song had been influenced by Bob Dylan, who had himself been inspired by Chuck Berry. Edwards was comparing a guitar riff from Brutal, the first track on Rodrigo’s album Sour, with Costello’s 1978 hit Pump It Up.

Much to Edwards’ surprise, Costello himself replied, writing: “This is fine by me, Billy. It’s how rock and roll works. You take the broken pieces of another thrill and make a brand new toy. That’s what I did. #subterreaneanhomesickblues #toomuchmonkeybusiness”

The primary source for this article was an interview between Kark Satlof for an on line broadcast of Freakonomics and from reportage by CNN Entertainment in 2021.

In our occasional re-postings Sidetracks And Detours are confident that we are not only sharing with our readers excellent articles written by experts but are also pointing to informed and informative sites readers will re-visit time and again. Of course, we feel sure our readers will also return to our daily not-for-profit blog knowing that we seek to provide core original material whilst sometimes spotlighting the best pieces from elsewhere, as we engage with genres and practitioners along all the sidetracks & detours we take.

This article was collated by Norman Warwick, a weekly columnist with Lanzarote Information and owner and editor of this daily blog at Sidetracks And Detours.

Norman has also been a long serving broadcaster, co-presenting the weekly all across the arts programme on Crescent Community Radio for many years with Steve Bewick, and his own show on Sherwood Community Radio. He has been a regular guest on BBC Radio Manchester, BBC Radio Lancashire, BBC Radio Merseyside and BBC Radio Four.

As a published author and poet Norman was a founder member of Lendanear Music, with Colin Lever and Just Poets with Pam McKee, Touchstones Creative Writing Group (for which he was creative writing facilitator for a number of years) with Val Chadwick and all across the arts with Robin Parker.

From Monday to Friday, you will find a daily post here at Sidetracks And Detours and, should you be looking for good reading, over the weekend you can visit our massive but easy to navigate archives of over 500 articles.

The purpose of this daily not-for-profit blog is to deliver news, previews, interviews and reviews from all across the arts to die-hard fans and non- traditional audiences around the world. We are therefore always delighted to receive your own articles here at Sidetracks And Detours. So if you have a favourite artist, event, or venue that you would like to tell us more about just drop a Word document attachment to me at normanwarwick55@gmail.com with a couple of appropriate photographs in a zip folder if you wish. Beiung a not-for-profit organisation we unfortunately cannot pay you but we will always fully attribute any pieces we publish. You therefore might also. like to include a brief autobiography and photograph of yourself in your submission. We look forward to hearing from you.

Sidetracks And Detours is seeking to join the synergy of organisations that support the arts of whatever genre. We are therefore grateful to all those share information to reach as wide and diverse an audience as possible.

correspondents Michael Higgins

Steve Bewick

Gary Heywood Everett

Steve Cooke

Susana Fondon

Graham Marshall

Peter Pearson

Hot Biscuits Jazz Radio www.fc-radio.co.uk

AllMusic https://www.allmusic.com

feedspot https://www.feedspot.com/?_src=folder

Jazz In Reading https://www.jazzinreading.com

Jazziz https://www.jazziz.com

Ribble Valley Jazz & Blues https://rvjazzandblues.co.uk

Rob Adams Music That´s Going Places

Lanzarote Information https://lanzaroteinformation.co.uk

all across the arts www.allacrossthearts.co.uk

Rochdale Music Society rochdalemusicsociety.org

Lendanear www.lendanearmusic

Agenda Cultura Lanzarote

Larry Yaskiel – writer

The Lanzarote Art Gallery https://lanzaroteartgallery.com

Goodreads https://www.goodreads.

groundup music HOME | GroundUP Music

Maverick https://maverick-country.com

Joni Mitchell newsletter

passenger newsletter

paste mail ins

sheku kanneh mason newsletter

songfacts en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SongFacts

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!