SEA FEVER, INDEED

SEA FEVER, INDEED

The first of an occasional series What A Poem Means To Me

by Norman Warwick

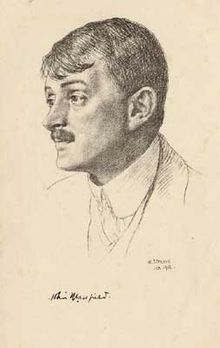

John Masefield (left) was a British novelist, playwright, and poet born on the 1st June 1878 in Herefordshire, England. Both his parents died before he turned six and he grew up under the care of his aunt, a woman who did not approve of his addiction to reading, which he developed at a young age. In 1891 he began a life at sea and spent several years aboard the HMS Conway, where he spent a lot of time reading and writing. In 1895, after a brief illness, he boarded a boat destined for New York, however, his passion for writing led him to abandon ship upon its arrival in the US and he spent several years living the life of a drifter. He returned to England in 1897 where he married, had children, and embarked upon what would later be a successful career as a writer. ‘Sea Fever’ appears in his first book of collected works, Salt-Water Ballads, published in 1902. In 1912 he was awarded the annual Edmond de Polignac Prize and was Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom from 1930 until his death in 1967, the second-longest period of office ever held, after Tennyson. Masefield promoted poetry throughout his life and organized competitions, prizes, and annual recitals.

John Masefield’s poem Sea Fever (right) is one of half a dozen poems I can never recite in public because the lump it brings to my throat makes me incapable of uttering a sound. It is perhaps his most well-known work and describes the poet’s longing to go to sea. Despite its first-person poetic voice, the principal theme of wanderlust is one that transcends the speaker and can be identified with by many, including this poetry teacher with a lump in his throat trying to tell his students how wonderful this work is.

Perhaps because Masefield spent time as a sailor aboard different ships he was able to effortlessly demonstrate his love for and affinity with this lifestyle. Sea Fever is brief and simple, yet its lyrical composition, repeated refrain, and poetic devices render it a perfect poem to be either read aloud or reflected upon in solitude.

Sea Fever seems to flow like music, yet in a way that we might think reflects the uneven rhythms of the sea.

That might explain why the poem remains so well-loved and such a firm part of the literary curriculum in English Literature in the UK. It is curiously satisfying to this pensioner that there are young students who are still, surely, falling in love with this poem in just the same way as I did, and my dad did, and who will carry it with them throughout their lives just as he and I did.

It has to be said that today´s student body seem to grasp essence of the poem despite the fact that sea travel, whether carrying cargoes or cruise lovers, has changed so much since Masefield´s descriptions. That is certainly true of this essay, taken from scores available on line, which looks for the meaning and methodology behind each stanza.

´John Masefield’s Sea Fever is perhaps his most well-known work and describes the poet’s longing to go to sea. Despite its first-person poetic voice, the principal theme of wanderlust is one that transcends the speaker and can be identified with by many. Masefield spent time as a sailor aboard different ships and therefore can effortlessly demonstrate his love for and affinity with this lifestyle. ‘Sea Fever’ is brief and simple, yet its lyrical composition, repeated refrain, and poetic devices render it a perfect poem to be both read aloud or reflected upon in solitude.

‘Sea Fever’ is formed of three quatrains; the first and second lines always rhyming to form one couplet, and the third and fourth rhyming to form a second couplet. The meter is heptameter but the types of feet are varied throughout the work and so the stresses on each syllable can change from line to line. However, despite its varying feet, it nonetheless seems to flow like music, and we may regard the irregular stresses as an attempt to mirror the uneven rhythms of the sea. Interestingly, although in the original version of the poem – published in 1902 – the first line of each stanza is “I must down to the seas again”, in later versions Masefield inserted the word “go”, altering both the verb and the meter of the refrain.

First Stanza

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

(…)

And a grey mist on the sea’s face, and a grey dawn breaking.

The first stanza begins with the refrain “I must down to the seas again”, which is repeated at the beginning of each stanza and gives immediate sense to the title. Although we may identify the poem’s theme as the desire to go to sea, it also deals with the very human yearning to connect with one of the most powerful natural forces on earth. A hugely common theme in poetry, the sea has always been a fascinating source of inspiration for many. Masefield demonstrates an obvious adoration for this wild and beautiful entity, and seems to almost compare it to a person, referring to it as “her” and describing her “face”.

The desire to connect with the sea is shown through the pursuit of a sailor’s life as he asks for a ship to sail. He does not describe the sea in the most classically beautiful terms, here she is “grey” and “lonely”, giving more mysterious and melancholic connotations, yet enchanting nonetheless.

The use of alliteration in the first stanza contributes to the musical tone with expressions like “a tall ship and a star to steer her by” and “the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking”. This also serves to render ‘Sea Fever’ more appealing to the ear, and we can imagine it like a sea-chanty, being sung by lonely sailors.

Second Stanza

I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

(…)

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

The second stanza appeals to all five senses. Masefield’s descriptions allow the reader to feel like we are standing on the shore; listening to the “sea-gulls crying”, watching the “white clouds flying”, feeling the coldness of the “windy day”, and the saltiness of the “flung spray and the blown spume” on our tongue and nose. Again, the poet emphasizes the irresistible pull of the sea as he repeats the word “call”. With the second repeated refrain “And all I ask”, he seems to be underlining the simplicity of the sea, perhaps in contrast to the complications of everyday life; as if the sea’s wild nature is something comfortingly consistent and familiar. Indeed, the poem’s meter, although not strictly constant does imply a certain steadiness, contributing to its lyrical, musical feel.

Third Stanza

I must go down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life,

(…)

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick’s over.

The third stanza of Sea Fever brings the theme of wanderlust to the forefront. Masefield speaks of the “vagrant gypsy life” and expresses a desire for a “laughing fellow-rover”. This final quatrain is full of positive imagery like “merry yarn” and “sweet dream”. However, the poet refrains from painting an idyllic picture of a life at sea with the use of the expression “the wind’s like a whetted knife”: a powerful image which stands out by way of its alliteration and the sudden introduction of this sharp, violent object. In addition, Masefield mentions the wind in all three of the poem’s stanzas, perhaps to draw attention to the way in which ships are influenced both by man and by two of the most powerful natural forces: the sea and the wind. Here, we can sum up the central message of the poem: life at sea is full of contrasts – cruel winds and wild waves in perfect harmony together with the sweet and endless freedom it allows.

The last line of Sea Fever broadens the scope of the theme, as it is slightly ambiguous in nature. The word “trick” in sailing terms refers to a watch at sea: four hours watching and eight hours rest. We may take it at face value and assume Masefield is again drawing attention to the simplicity of a life at sea, emphasized by the wonderful balance between work and rest. However, if we step back and take into account the universal nature of the two principal themes – the draw of the sea and the desire to travel – we may see the “long trick” as a reference to life in general, and “quiet sleep” as a peaceful death, allowing for a “sweet dream”, which is knowing we may rest in the afterlife in the knowledge that we worked well and lived truly. In that sense, the whole poem may be seen as a metaphor for life; with the sea representing a modest and humble way to live, more in touch with nature, and therefore better equipped to deal with any storms that may come our way.

However, ‘Sea Fever’ is undeniably a demonstration of the poet’s love for the sea and the life of a sailor. It is the poem’s modest simplicity and the relatable nature of these themes that allow us to draw certain conclusions from it with regards to our individual lives, a fact that makes the poem truly a work of art.

SEA FEVER by John Masefield

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by;

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face, and a grey dawn breaking,

I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

I must go down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life,

To the gull’s way and the whale’s way where the wind’s like a whetted knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover,

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick’s over.

For me, it remains a poem I reflect on now every day of my life, Where I live here on Lanzarote I have only a short walk to the sea front of Playa Blanca, a former fishing village and now a tourist resort and sea-faring harbour, newly built to accommodate mid-size cruise liners, ferries around the local islands and of course, team and one man fishing boats.

I ´down to the sea´ every day and though day breaks here usually in a burst of sunlight, there is the occasional grey dawn breaking as if nature is creating the scenery to guide my thoughts. The sea, that can be viewed from anywhere on the island, sometimes in a 360 degree vista, is, as I think Masefield acknowledges, much more than just a part of the scenery. Its tides carry this island´s history, or the history of the UK in the ebb and flow of battles won and lost. The sea, here, is an indicator of the island´s economy, and generator and detractor of riches.

Our local press here ran an interesting article recently.

´The mayor of Yaiza, Óscar Noda, (left) was clear and resounding in the meeting with supra-municipal administrations when claiming the docking of medium-sized cruise ships in the 300-meter-long mixed-use dock of the new Playa Blanca port, warning “that Yaiza, and we have already said it, it does not intend to compete with Arrecife.

Our port is a complementary facility that does not allow large cruise ships to dock, but the fact that medium-sized cruise ships come to the south of the Island benefits Yaiza, and of course, the island as a whole, in such a way that we cannot be dismissed as unsupportive, and the most logical thing is to make the most of an investment of 40 million euros “.

In defence of the interests of his municipality, the mayor explained Yaiza’s feelings to the Minister of Public Works of the Government of the Canary Islands, Sebastián Franquis, and the president of the Cabildo of Lanzarote, María Dolores Corujo, during the visit to the port on the occasion of the partial reception of the works that already reach 90 percent of execution, with the forecast that the installation will be operational and with all its services at the beginning of 2022.´

The redevelopment a few years ago of the port of Arrecife (right) to accommodate the massive cruise liners is viewed as a great success and has been massive income-generator to the city via an increased footfall of passengers disembarking to spend money in the high end shops around the marina and on the fancy multi national cuisine of the many fine restaurants. It is, perhaps, understandable that, having seen that income source dry up during the two years of covid, the city of Arrecife might be fearful that the new port in Playa Blanca might dilute some of Arrecife´s future income, but it seems to me that surely the two ports could complement each other in such a way that there is income for both and increased prosperity for the island as a whole..

There are complaints from tourist visitors that the harbour wall reduces the view of the sun dropping diamonds down the coast and island of Fuertaventura some twenty miles across that star crossed sea. Local shop-keepers and restaurant owners are hoping the small cruise ships will bring passengers in search of ´I´ve been to Lanzarote´ t-shirts or looking for fantastic food at affordable prices, whilst hotel owners are worried the liners might steal passengers who would have otherwise arrived in a plane and stayed at their premises. Towns along the coast between Playa Blanca and Arrecife, some thirty miles away, feel discouraged that those two locations might attract more than their fair share of tourists,…and tourist income ! Some on the west coast of the island, which is only about twenty miles across at its widest point, might even feel resentful of the east coast´´ and its income,…..although its all Lanzarote income,…… isn´t it ?

Sea fever indeed.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!