JAZZ MUSICIANS PLAYING VIOLINS and UK jazz news

JAZZ MUSICIANS PLAYING VIOLINS

and UK jazz news

by Norman Warwick

Before we introduce you to jazz musicians playing violin may we at Sidetracks And Detours just take the opportunity to share some good news from our friends at Jazz In Reading of forthcoming events in July?

Following hard on the heels of the successful release of the Back To Blue Note album in January of this year, Stuart Henderson will be bringing his celebration of the classic Blue Note record label to two live events in July.

Organised by our good friend from Guildford Jazz, Marianne Windham, Wood Street Jazz Festival, will take place on Sunday 18th July. Stuart and his Quintet will be joining an all-star line-up, comprising Dennis Rollins and his Velocity Trio, vocalist Louise Clare Marshall and the Somethin’ Else Big Band.

It’s a fun family event that takes place between 12.30pm and 5.30pm on Wood Street Village Green, Guildford, so you’ll need to bring your picnic rugs and chairs, sunscreen and umbrellas, for a wonderful afternoon of fantastic live jazz in support of Challengers, a charity dedicated to providing inclusive, exciting and fun play and leisure for disabled children and young people across the South East.

Delicious Indian cusine will be available to order from the Shaeen Tandoori Restaurant and there will also be wood-fired pizzas, ice creams and a real ale bar.

Tickets booked in advance are £20 each or £36 for a household of two (under 18s free) are available from

www.disability-challengers.org/jazz-fest or call 01483 230060

On Friday 23 July, The Flowing Spring, Playhatch will be playing host to Stuart’s Back to Blue Note Quintet. The gates will open at 6pm and the band will play at 9pm. Tickets available @ £12.00 here

Stuart Henderson tells us that ´The two words´, Blue Note, immediately evoke the unique sounds and visual images of this classic jazz record label. Founded by German emigres, Alfred Lyon and Francis Wolf, in 1939, the label enjoyed its greatest days in the 1950s and 1960s with a stunning catalogue of innovative records. One hit record followed hard on the heels of another by the brightest stars in the jazz firmament – Art Blakey, Clifford Brown, John Coltrane, Herbie Hancock, Hank Mobley, Lee Morgan, Horace Silver and Jimmy Smith amongst a host of others.

It is my great privilege to play some of these fabulous charts today in the company of a brilliant band comprising Ollie Weston tenor saxophone, Tom Berge piano & organ, Raph Mizraki bass & percussion, and Simon Price on drums´.

Back To Blue Note was well reviewed on The Jazzmann blog

The album is available as a digital download here

but please check the Jazz In Reading web site if you have any difficulties.

Meanwhile, we at Sidetracks And Detours would like to steer you towards the JAZZed publication created for jazz educators and providing practical, hands-on information to help school and independent music educators teach jazz to high-school and college students. And after learning soemthiong of their good work, perhaps you might care to visit their digital on line edition site which enables those who love jazz to click a button to support the publication and the great projects it promotes.

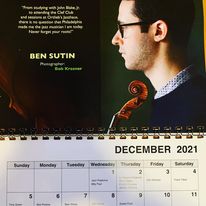

Benjamin Sutin, (right) who contributes to the publication and its on line digital editions is an eclectic, diverse and sought-after New York City based jazz violinist, violist, pianist, composer, and educator. He began his career in Philadelphia where he studied with legendary jazz violinist John Blake Jr.. Sutin has since performed in such venues as Carnegie Hall, NJPAC, Lincoln Centre, The Apollo Theater, Birdland Jazz Club, and The Kennedy Centre. He has worked with the likes of David Amram, The Big Apple Circus, Banda Magda, Vince Giordano, Larry Harlow, Elio Villafranca, and Bobby Sanabria. Sutin appears on Sanabria’s 2018 Grammy-nominated album, West Side Story Reimagined. On November 18, 2020 Sutin released his third album as leader, Hard Bop Hanukkah (MEII Enterprises), recorded live at Rockwood Music Hall in New York City. Grammy-award winning jazz violinist Regina Carter calls Sutin’s arrangements and performance “Exceptional!” World-renownrf klezmer and classical clarinetist David Krakauer lauds the album as “. . . a great listening experience!”

Not being as deep rooted in the genre as my fellow joined up jazz journalists (I come from ´country´fields) I didn´t know any of this until I researched Ben Sutin after reading his wonderful article in recent edition of JazzEd.

His piece in JAZZed magazine basing it on a quote from an earlier interview with Wayne Shorter, (left) an American jazz saxophonist and composer. Shorter came to wide prominence in the late 1950s as a member of, and eventually primary composer for, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. In the sixties, he went on to join Miles Davis’s Second Great Quintet, and from there he co-founded the jazz fusion band Weather Report. He has recorded over 20 albums as a bandleader and I think it safe to say Shorter has established his credentials !

Shorter, apparently, described his band line-up to Ben as being of ´jazz musicians who play violin, not of violinists who play jazz !

It is a moot point worth exploring, and in his article, which borrowed its title from that quote, Sutin did just that, and very thoroughly.

The article contends that there are not many instruments better fit for jazz than the violin. Jazz has grown and transformed and progressed rapidly over the past few years. Nevertheless, the very roots of jazz come from the melding of African slave rhythms, soul, and melody with Western, European harmony in New Orleans. Since then, says Mr Sutin, without fail, jazz has continued to change with the times, about once a decade, constantly adapting to and fusing with the new popular music and cultural nuances of the day. It is a vivid beauty of jazz that it constantly embraces new influences which further inform and the music and lead it towards new horizons, while retaining its unique jazz identity.

The JAZZed contributor suggests, more specifically, that jazz has witnessed perhaps its most pivotal transformations and contributions from a handful of individual artists who went well beyond using the popular music of the day as inspiration.

´Instead,´ he says, ´they infused their own personal backgrounds, stories, cultures and unique voices into this universal musical language of groove and improvisation we call jazz. The chorus of all these unique voices is what makes jazz so special and forever changing, like a never-ending choral.

He further argues that the violin is an instrument that lends itself perfectly to this aim. The mass public perhaps most instantly recognises the violin for its place in Western classical over the last hundreds of years, the instrument in fact has a rich and extensive history of prominence in a myriad of folk music traditions from around the world, including the United States to where mass immigration carried sounds from all over the world. Combined with an ever changing gig economy, the age of globalization and the Internet, it is highly likely anyone learning to play violin today will be inspired by, or eventually play, a multitude of genres. The advantage violinists have over most other instruments in jazz is that their very experience as professional musicians gives them more opportunity to explore these different paths and traditions (from classical music to world music and beyond) in a much more streamlined and accessible way than a saxophonist or trumpeter would, for instance.

Mr Sutin reminds us that ´this is, of course, all in addition to the often ignored and overlooked but nonetheless remarkably extensive history of violin in jazz itself.

He then gives a potted history.

´It all started on September 16, 1903 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the alleged birthplace of Italian-American violinist, Joe Venuti. Classically trained from an early age with a steep knowledge of music theory (which he learned from his grandfather), Venuti would soon begin experimenting with jazz along with a friend whom he met in the violin section of his public school orchestra. This friend was Salvatore Massaro ,who later changed his name to Eddie Lang and switched instruments from violin to guitar. Little did Venuti know he would become the pioneer of jazz violin. By the mid ‘20s, Venuti was on the road, already making a name for himself, his distinct sense of humour, and for his instrument. Just a few short years later in 1928, French-Italian violinist Stephane Grappelli (b. 1908) would hear Venuti playing jazz in Paul Whiteman’s Orchestra. The rest, as they say, was history.

French jazz violinist Stephane Grappelli as part of the David Grisman Quintet for a filming ofKQED’s “Over Easy” television show in San Francisco , 1979.

(Photo by Jon Sievert/Getty Images)

Grappelli’s upbringing wasn’t easy. His mother died at five. At 10 his father was drafted into the army at which point he lived in an orphanage until his father returned. He started studying violin at age twelve and moved to Paris to study at the Conservatoire de Paris. By fifteen he was busking on the streets to support himself, opting to live on his own out of dislike of his new stepmother. Although he was receiving formal training, Stephane much preferred watching and learning from the fellow street performers in Paris at the time; a clear homage to his roots of self-independence and driving curiosity. After a brief stint of switching gears to focus on piano where he sharpened his harmonic ears,

Grappelli was convinced to pick the violin back-up. Shortly thereafter, in 1931, he met French gypsy jazz guitarist, Django Reinhardt. However, it wasn’t until 1934 that the two would begin their dynamic career together in what we now know as the Quintet Du Hot Club De France.

This said, violin made its first appearances in jazz long before these legends Venuti and Grappelli put the instrument in the spotlight. As early as 1900, the violin was a frequently used lead instrument in ragtime and territory bands. In fact, it was in Alphonso Trent’s Territory Band in the 1920s that Stuff Smith first made his mark. He would later begin experimenting with playing violin amplified (the first to do so), hoisting the instrument to new possibilities. Through the 1930s and ‘40s we see Claude Williams playing violin in the Count Basie Orchestra, Edgar Sampson with the Fletcher Henderson Big Band, and Eddie South with Jimmy Wade. Even Artie Shaw, Tommy Dorsey, and Earl Hines featured strings in their bands, and soon enough we would see Ray Nance doubling on violin in Duke Ellington’s orchestra as part of the ensemble, as well as a frequent soloist. Meanwhile, Ginger Smock out of L.A. (who was extremely influenced by Stuff Smith) was making an impressive name for herself locally. In fact, her career is quite impressive when thinking about the fight she endured as an African-American woman who played jazz violin.´

Ben Sutin does not forget to mention the man who invented the long tradition of singing during his solos, and submits the name of Ray Perry (who frequently performed with the likes of Lionel Hampton and Ethel Waters) as the first known jazz musician to do this, later inspiring Slam Stewart to carry forward a tradition still avidly practiced to this day.

It is well documented that the be-bop years saw a slight decline in jazz violin prominence because of a lack of proper violin amplification and recording techniques to effectively compete with the horn players leading the bands of the time. That has been alluded to by several of the musicians reported on by our joined up jazz journalists here at Sidetracks & Detours. They have reported how in the years ´with record labels controlling everything´ jazz violin as a result, would slowly peak off.

Radio-play had a direct impact on what was booked at the clubs and if violin couldn’t be recorded then it would be unlikely to hear it in the clubs. There were of course a few exceptions. As mentioned earlier, Stuff Smith learned to amplify his violin early on and was able to stay relevant, performing with the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Coleman Hawkins, and Oscar Peterson. But unfortunately, few others ever got the real opportunity to break their way into the be-bop scene.

As jazz marched through the nineteen sixties and seventies, Mr Sutin explains, ´a whole new generation of jazz violinists begin to make their mark with the advent of the electric violin and new emerging eras of jazz, including jazz fusion and avant-garde jazz. A few of these noteworthy pioneers within the jazz fusion idiom include Jean Luc Ponty (who began playing straight ahead jazz on the local Paris scene in the ‘60s), Didier Lockwood, Zbigniew Seifert, and Michael Urbaniak, among countless others. Then we see violinists such as Leroy Jenkins and Billy Bang (who played with Sun Ra) in the late seventies, both highly influenced by the blues, the church and the civil rights movement.

´During this same period in Philadelphia, John Blake Jr. was getting his career under way, performing with the likes of Grover Washington Jr, McCoy Tyner, Kenny Barron, Dr. Billy Taylor, and others. Blake was classically trained and steeped in bebop vocabulary and was also highly influenced by the church, gospel music and negro spirituals. He even studied Carnatic Indian fiddling as well. His awareness and receptivity of such sounds gave him not only his distinctive and effortless control and mastery of the instrument, but also a deep understanding of the global jazz ´esperanto´, combined with a voice of soul on his instrument, creating a sound completely uncharted before on the violin.

Most importantly, Blake is seen by many as having been solely responsible for where jazz violin is today thanks to his incredible career as an educator. His students include Christian Howes (today’s most sought after jazz violin educator, spreading jazz violin to thousands of people all over the world), Regina Carter , Sara Caswell, Jeremy Kittle, and David Sutin himself, among others.

Other prominent jazz violinists of today include Zach Brock (of Snarky Puppy), Jenny Scheinman (who beautifully blends American folk music with jazz, frequently performing with the likes of Bill Frisell), and Mark Feldman (John Abercrombie, John Zorn), and plenty more beside them

Each one of these jazz violinists mentioned above contributed (and continue to contribute) a great deal to not only violin as an instrument, but also to jazz as a whole. They all transformed how we conceived violin and each was ground-breaking in showing the world what was possible on the instrument, challenging the notion of it being singularly classical. These artists paved the path forward for more to follow in their footsteps. Beyond that, however, each of them contributed something beautiful to the world of jazz.

´Not one of these jazz violinists sounds like another,´ Sutin opines. ¨They are all true jazz musicians in that they are each their own, expressing a chorus of unique musical voices, all crafted from their own individual experiences, cultural backgrounds and musical tendencies and desires, most of which are a direct result of the abundance of possibilities only available to the violin, and many of which would have never otherwise made its way into the already enormous vocabulary of jazz.´

There is no doubt that Sutin has followed the example of his many heroes listed above, and that they were instrumental, if you will pardon the pun, in the way he has dedicated his career as a band leader and composer to implementing the music of his heritage into his life as a jazz musician.

´It is unabashedly genuine to who I am as an artist and a jazz musician,´ he admits. ´It is my unique voice and allows me to express my deepest of emotions through my music, just as Leroy Jenkins and John Blake were inspired by the church. Absorbing the traditions of klezmer fiddling, Latin jazz, rock, Middle Eastern music, and classical music has all been unbelievably fruitful to changing the way I approach my instrument, improvising, writing, and playing jazz as a whole. It’s opened up a brand new doors for me that I would never have otherwise experienced, at the same time offering something novel, fresh, and exciting to the world of jazz and jazz violin as we know it.´

He encourages any student of jazz violin to begin the journey of finding their own voice on an instrument that provides us with so much. Serious soul searching will be rewarded in the end for player, for violin and for jazz at large.

Mr. Sutin concludes that ´jazz violin is so much more than what most people tend to know and recognize, saying Gypsy jazz was not the end, but merely the beginning. Jazz has no end, nor does the violin. Therefore, neither does jazz violin!´

The musician and writer for JAZZed is not alone in this thinking. Remember Wayne Shorter says that ´Jazz means “I dare you,” but I’ll go one step further: jazz violin means, “I dare you.” Just remember, we are jazz musicians who play violin, not violinists who play jazz.´

That is an attitude I had previously heard expressed slightoly differently over in the ´country-fields of Americana , by the Texan singer-writer Guy Clark, in the song Picasso´s Mandolin off his Boats To Build album.

Anyone familiar with the painting (draft shown left, final version on cover and at top of this article) that gave the song its title will be aware the mandolin created by the Spanish artist is so unconventional in shape and colour as to almost unrecognisable as a mandolin.. It seems to be more an extravagant representation of some imagine musical tool.it looks as if he had learned what a mandolin looked like and had re-drawn it in almost stream of consciousness fashion.

Guy´s song lyrics encourage musicians to play in a similar fahion, and in doing so he creates an extraordinary song. The message from from messrs. Sutin, Shorter and Clark seems to echo an acronym I learned, I think, in my days as a Trustee of the revenue-funded SpiralDance (now Can´t Dance Can) that did so much wonderful community work by precisely (but not too precisely !)following that message.

CIP

Copy. Innovate, Practice

I took that as advice to learn from the best of the past, add to that learning your own current state of heart and mind to create art to reach into the future.

sidetracks & detours

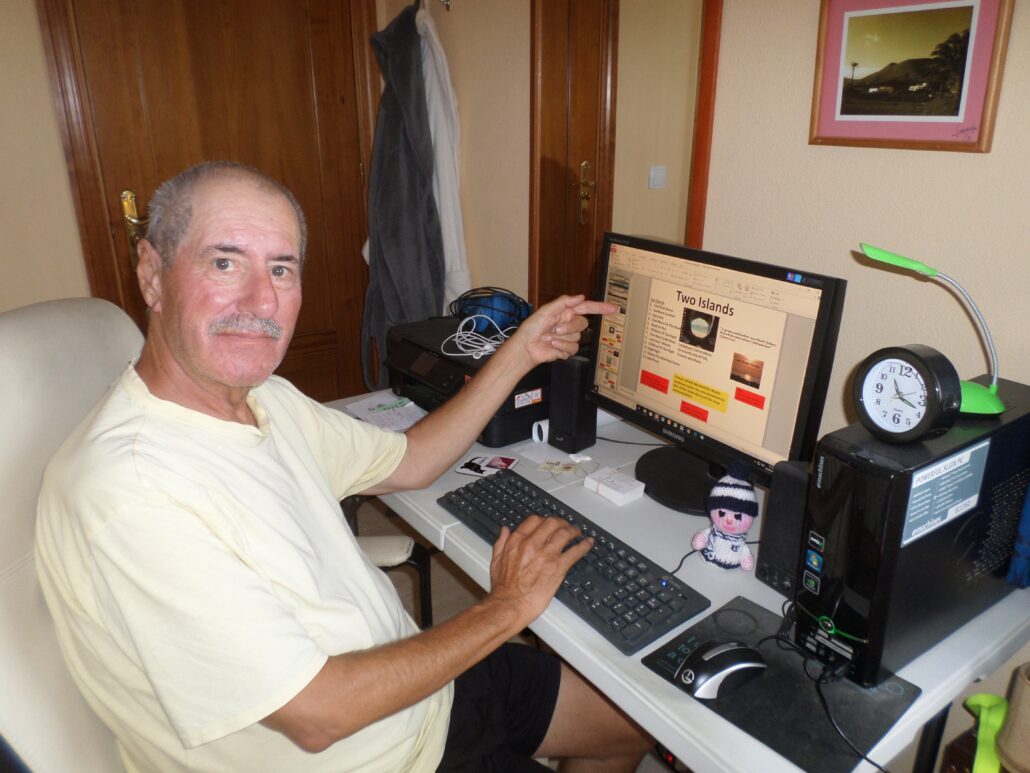

This article was collated by Norman Warwick, owner and editor of Sidetracks And Detours. Norman, who also writes a weekly arts column for Lanzarote Information is a writer and broadcaster, poet and songwriter and is one of four founding members of Joined Up Jazz Journalists, JUJJ, formed in 2020. JUJJ members will share their own enthusiasm for jazz to grow their own knowledge of the genre to better serve readers and listeners and to become part of a synergy of media already serving the jazz scene. The other members of JUJJ include Susan Fondon, Norman´s colleague from Lanzarote Information who writes and conducts interviews on the island´s live jazz events. Jazz historian, researcher ad writer Gary Heywood-Everett is also a member, along with writer and broadcaster of Hot Biscuits jazz programme on www.radio-fc.co.uk , Steve Bewick, a former co-presenter with Norman for five years of the of the all across the arts radio show. JUJJ has already borne fruit by hosting the inaugural annual Joined Up Jazz Festival earlier this year, enjoying support from the likes of Ribble Valley Jazz And Blues Festival. Steve Bewick took JUJJ one step further when working with Hoàng Minh Châu, writer of the Hanoi Jazz Lovers blog, to create The Birth Of A New Cool published on Sidetracks And Detours on 28th May 2021, thus introducing us more than 7,000 potential new readers. Today´s pages were created with reference to Jazz In Reading, Guildford Jazz and Jazzed magazine as primary sources.

We are always delighted to receive submissions from readers so if you have any news, reviews, interviews or reviews of favourtie art forms or practitioners please feel free to submit them as a Word document e mail attachment to

normanwarwick55@gmail.com

Because any work subsequently published will be fully attributed you should also feel free to include a short biography of yourself and a jpeg of yourself for inclusion. If you wish to include photographs to complement your article that would be welcome but don´t worry if not, as we do have extensive photo archives of our own.

We thank you for your interest and your time.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!