MIME, MIMICRY AND MUSIC by Michael Higgins

MIME, MIMICRY AND MUSIC

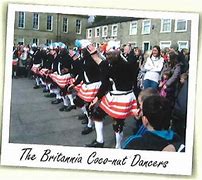

the very colourful Britannia Coconut Dancers

by Michael Higgins

Earlier this year the Morris Ring, founded in 1934 as an umbrella organisation for the then rejuvenated Morris dancing teams of England, informed one English folk dancing troop, The Britannia Coconut Dancers, to stop blacking their faces or forfeit their membership benefits, including group public liability insurance. The Ring’s own membership, heirs of research on the dance by musicologists, composers and folklorists at the turn of the 20th century, has since the Thirties grown substantially. The phrase ‘folk dancing’ and ‘folk music’ had been coined by them for such rustic dances – a borrowing from the German ‘Volkstanzen’ and ’Volksmuzik´, which literally mean ‘race’ dance or music, a term meant to excite the growing German desire for racial and linguistic unity. It was meant to convey a ‘folkiness’ or ‘peasantry’ connotation in English.

This romantic endeavour to preserve an almost lost male art form seemingly dead or dying out in the English country villages, was carried out in the early 1900s by the likes of Ralph Vaughn Williams, George Butterworth, Cecil Sharp and others, resulting in an informal education programme which had by the 1970s led to scores of dancing teams performing dances as published or taught by other overarching groups such as the English Folk Dance And Song Society. Morris dances were still traditionally performed by men, and the dances were mainly from the popular Cotswold area of England with handkerchiefs in hand and bells on knee. And all the faces were white. Well, … almost.

It was in the heady mid-seventies, after a spell abroad, that I started researching folklore and Morris dancing myself. I spent a spell as a trainee in a Morris Ring affiliated team, led by a school teacher, where a quaint semi-romantic nomenclature existed – the leader being known as a ‘squire’ and a treasurer as a ‘bagman’. Along with the name ‘Morris’ (and the almost Tolkien name ‘Ring’) came a whole heritage of customs and behaviour attributed to the vanished past, a heritage I and my fellow dancers were expected to carry on to the best of our ability. Indeed the Morris Ring vowed ‘to encourage the morris, to maintain its traditions and to preserve its history…’, adding, ‘The purpose is not to replace or supersede the existing organisations, but to subserve them.’

The 1970s decade was the heyday of modern folk and pseudo folk music, breeding the likes of Steeleye Span, Lindisfarne, Jake Thackray and Mike Harding, And it was the age of feminist interpretation in dance too, arguing that this ‘man’s dance’ should not be for men. Indeed, in the north west of England and to the south of Rochdale, where I live, young girls had indeed for a while adopted male Morris dancing attire and performed an altered version of the dance in judged carnival competitions in the 1920s and 30s whereupon it had become by my day unrecognisable as a folk dance.

Here the traditional man’s dance had been simplified and feminised. I recall seeing The Royton Traditional Morris Dancers (all men and boys) when I was a boy and expressing surprise to my mother that men could do such things.

The Royton men used the traditional swinging be-ribboned cotton rope ‘slings’ in their hands, wore ribbons, neck beads and knee breeches and danced in bell covered clogs, accompanied by a concertina band. And the only ‘squire’ they would admit to were two dancers who shared this as a forename. This was the famous team revived by Cecil Sharp’s assistant Maud Karpeles in 1929 after fifteen years of decline but at least forty years of existence. I never dreamed at the time that I would one day dance in this team as leader and conductor and retrace its history back to the 1870s, and to its own forebears in the area back to the late 18th century. In the records all faces were white but as far back as 1800 there had been a romantic desire for the young men to outdo ‘Indian princes’ in their splendorous dress.

Yet even as a young man dancing in the late twentieth century, no English traditional dancing team had the same Romantic clout, or visible presence, as the black-faced, skirt wearing, clog dancing ‘Coco Nut Dancers’ of Bacup in Lancashire just to the north of Rochdale. They, and the Stacksteads Silver Brass Band, danced the town boundaries every Holy Saturday (the day before Easter), on the streets, in public houses and at some points splitting up to dance in private houses. Allegedly formed in 1857 by Abraham Spencer (1842-1918) as the Tunstead Nutters, then being only one of at least five teams in the area, they were eventually reformed in 1903 at the local district of Britannia by a quarryman named James Mawdsley, giving them their modern name. And, as in Royton, Maude Karpeles had also interviewed them while she was in Lancashire ninety years ago.

Their knee breeches, covered by short skirts, and the rosette bedecked bonnets or turbans they wear, are one thing but the black faces are another, and in recent years there have been calls for them to stop blacking up. In my dancing days the black faces were the wonder of the region and many theories were advanced to account for this.

Some thought the blackened faces represented the swarthy or sooty Cornish miners brought in to serve local collieries. Others reckoned blackening faces was to acknowledge the true descendants of the original medieval Morris dancers, the North African dark skinned Moriscos or ‘Moors’ from whom the Morisco or prototype Morris Dance was named. Faces may, though, have been blackened first when imitating the danse des Cocos of France; the general Coco dances of Spain, Portugal, and by descent, South America.

Today there is a whole research genre around the word Coco, derived from the coconut fruit and its by-meaning of ‘skull’. Research is being carried out into the emergence of the hollowed out coconut, or much easier to hollow out pumpkins, used as candle lanterns during Hallowtide and All Souls (Oct 31-Nov2) in the Iberian Peninsula.

This was discussed by Norman Warwick in his article Those Who Come Calling At Halloween post on Sidetracks & Detours and still available in our archives

Some wonder if the blackened faces were intended to evoke the frightening Coco spirit with his shadowy visage and ghastly appearance. The fact that the Britannia Coconut Dancers perform at Eastertide (and not Hallowtide) only adds to folkloric mystery as it was formerly supposed they danced for the regeneration of earth and souls in concert with the Easter Message. Until 1752 New Years’ Day fell on March 25th (Lady Day) and this ushered in the spring. As the moveable feast of Easter falls near this date what could be more springing than dancing in the new year and adding a pagan ‘lucky black imp’ castanet dance to the resurrection story of the Gospels? But when did they start dancing at Easter and not at the usual Summer Wakes?

And they wear them as castanets on the hands, and as clapping pads on thigh and waist. All the more suggestive of the pads used for crawling along mine tunnels some argue- although the skirts and turban bonnets are a mining mystery. They also have miming sessions in the dance, cupping hands to ears as if listening for danger and pointing to one another in turn. Just like the grime faced ladies in the weaving sheds, lip reading and miming amid the noise of clattering looms? Are the dance team, then, representing the dark spirits of a dusty fibre-blown world let loose when the end o’th’ day whistle sounds, repeating the clacking of those looms?

The Morris team also have a Whipper-in with appropriate whip too. Does this call to mind some devilish masters of the hunt searching an unknown prey? Who knows? But they do dance along the street in double files to the main tune of the Tip Top Polka melody, in step with the music of their founding time. Ironically their forebears had the presence of mind to copyright their music before Folk Dance buffs could get their hands on it. Again very modern.

They blacken their faces which some, mainly white people, object to as not being in step with these times. And again those exotic stage show skirts and turbans are said by some to mock South Sea Islanders or African tribesmen. But who are they really mocking?

All this may simply be following an old tradition of mere disguising once done with hearth soot. on the other hand, some people point out that face-blackening is similar to the cross-dressing ‘Sooty Betty’ of old festivals with sooty face and hearth sweeping broom. It is all seen by others as simply a Victorian joke. One TV programme in the 1970s amusingly portrayed the Nutters as a greeting party for African delegates on a tour of the North.

‘Ah they’ve blacked their faces in our honour…’ went the dialogue. No one at the time suggested they were dancing black-and-white minstrels or any such lampooning of dark skinned people. They were, well….just the Nutters.

And during my researches I found a reference hinting that the black faces may date back to even earlier than the eighteen fifties..

Lancashire novelist, Margaret Rebecca Lahee, wrote in the mid nineteenth century of black faced Morris Dancers beating time with castanets in their hands at the time of Lord Byron’s visit to Rochdale earlier in the century. This was a work of fiction based on the August Rushbearing holiday, Byron’s two visits in 1803 and 1811, and local hearsay of course, but intriguing none the less. In the novel these dancers however did not wear skirts and turban bonnets.

But all the modern coconut dancers’ ancient ‘dancing luck’ changed in the first decade of the 21st century, with calls for them to cease blacking up on the grounds that it was a racist gesture and insulting to ‘people of colour’- itself a clumsy term for those who used to be disparagingly called ‘coloured’.

After the George Floyd murder in the USA and the Black Lives Matter furore this year, the call was heeded by the Morris Ring who issued a decree in 2020 that all dancing teams which blacked up should cease immediately or lose their group insurance and other support. As this applied only to a minority of teams, such as the Nutters and the ‘Welsh Border Morris’ tradition, this felt to some like ‘constructive dismissal,’ a decree all the more devastating for local tradition itself.

After much debate the ‘coconut men’ decided to keep their traditional black faces and leave the Morris Ring, a decision which has poised the rather artificial Ring, ostensibly formed to preserve Morris Dancing tradition and custom, against one of the oldest and powerfully visible traditional teams of England in asking it to ditch its tradition on merely political grounds.

I am sure Cecil Sharp and the pioneers of the English Folk Dance and Song Society never envisaged this.

One can admire the Nutters´ pluck but going alone against the powers that be means finding money for public liability insurance and relying on a non-political public to support them. Currently they have plenty of support from their local community and the far flung international lovers of odd local traditions.

Just as the Lewes bonfire night committees in England keep alive the custom of burning various pseudo Catholic ‘Guys,’ and even the Pope on November 5th, and the Netherlands people still cling to their Sinterklaas (St Nicholas) and his dubious Moorish Swarte Piets (blacked up assistants) who traditionally accompany him from southern Spain for St Nicholas’ Eve on 5th December, oddities such as the Nutters will keep hovering in our backgrounds. But is this to let us know that the real folk, the people, the lower orders etc., will always be at war with the seemingly holier than thou higher orders who try to control them? Like the Nutters, Swarte Piet (Black Peter) is now under threat too.

Supporters argue that by standing up to the elitists they are portraying true black-faced courage, and to give in to the critics would be lily white surrender and a betrayal of everything they dance for: tradition and local pageantry, a magical world where working men can transform themselves into symbols of fairytale, phantasm and an other-worldly spectacle.

We will have to see how the future dancing pans out. Can the recognition that Black Lives Matter survive this parallel era of clumsy virtue signalling anger and see reason and proportion prevail?. If it does not then it is not just black faces that may be lost, but turbans, skirts, clogs, or anything else that may be imagined as offensive. Even coconuts and the mysterious men who make them speak.

Is unreasoned disapproval what the Nutters are listening for when they cup their ears in the dance? Or is it another, happier sound altogether?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!