GOODBYE TO A GYPSY SONGMAN

JERRY JEFF WALKER. Gypsy Songman

by Norman Warwick

I don´t think I´d heard of Jerry Jeff before hearing Pete Benbow sing his songs but Jerry Jeff Walker became one of the first artists of his kind I saw perform in the UK. In fact I´m pretty sure I travelled across the country to see him for the first time.

Jerry Jeff has held his place high on my most played list for decades now, though in truth he has perhaps the least number of song entries amongst his peers.

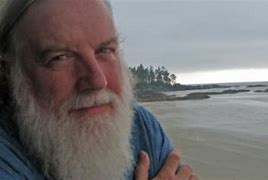

Much as I loved several of songs, Jerry Jeff Walker, (right) who lost his multi-year battle with throat cancer recently at the age of 78, always slightly puzzled me. He wrote one of the most enduring songs of the nineteen sixties in “Mr. Bojangles,” but he wrote plenty of what I snottily condemned as good time bar room songs, although now at the age of sixty eight myself, and having lived through this covid crazy year I am prepared to acknowledge that thios songs serve a real purpose these days ! In fact, Jerry Jeff arguably had a bigger impact by singing other people’s songs. he was a crucial catalyst in launching what became known as the Texas Cosmic Cowboy movement.

Geoffrey Himes, of course, that honest and much trusted writer for Paste magazine on line, has written a comprehensive summary of Jerry Jeff and his career.

Born and raised in upstate New York he was hardly an authentic Texas Cosmic Cowboy, and in fact his name of Jerry Jeff Walker was name he came up with to promote the image of the cowboy life-style.

His real name of Ronald Clyde Crosby (born on March 16, 1942, in Oneonta, N.Y) just wouldn´t have cut it.

His name was undergoing some change even when he joined the National Guard and went absent without leave under the name of Jerry Ferris, thanks to the borrowed ID of a fellow guardsman. in absentia the man who would become Jerry Jeff Walker hitchhiked around the country and wound up in Louisiana.

Singer writer and guitarist Chris Smither, (right) who has just released More From The Levee, a follow up to his earlier fifty-year career retrospective is a man who has seen the careers of many great fellow recording artists in that time.

´The folk music boom of the Fifties and Sixties barely touched New Orleans,´ Chris Smither told Geoffrey Himes in 2014. ´The Quorum Club on Esplanade had folk acts, and I used to go down there to hang out. This guy Jerry Ferris played there and I thought he was pretty good. Many years later I opened for him when he was calling himself Jerry Jeff Walker. But (that music) was a fringe thing in New Orleans; it has always been a horn and keyboard town.´

Back in Greenwich Village, Ferris renamed himself Jerry Walker, apparently after Harlem jazz pianist Kirby Walker. At that time Jerry Jeff was just one of a thousand guitar-strumming, singer-songwriter awakened by Bob Dylan. So he joined a psychedelic-rock band called Circus Maximus for two albums, before drifting back to the folk scene in the Village. David Bromberg, Emmylou Harris, John Hartford, Bryan Bowers, Peter Tork, (later of The Monkees) Carly Simon, James Taylor, and Robin & Linda Williams et al frequently delivered short gigs at the basket houses, where artists played half-hour sets for the tips the basket was passed around.

With a new album of wonderful music and musicianship recently released in 2020, David Bromberg emerged at round about that time.

´We were dreadful poor,´ Bromberg told Geoffrey Himes in 2006, ´because you don’t make much money passing a basket around…. But the poorer people are, the more they share. At four in the morning after the bars had closed, we’d go to the Hip Bagel to eat or to someone’s apartment to share a bottle and our newest songs. You’d play, and if someone liked the way you played, they’d say, ‘Let’s get together later….’ The first night I met Jerry Jeff at a party at Donnie Brooks’ apartment. He played Mr. Bojangles. How can you beat that?´

Legend has it that Bromberg called up Bob Fass, who had a midnight-to-dawn show on WBAI-FM, and told him he’d found this great songwriter and wanted to bring him to the studio. Bromberg had to drag the reluctant Walker to the radio station, but once the singer was there, he recorded several different versions of Mr. Bojangles for Fass, who played all the versions every night on his show. Before long, every folk fan in New York wanted to buy a copy of the song and every record company wanted to release it.

Actually, just to correct that Vanguard was perhaps the one label not keen to release the song, which was unfortunate because they held Walker’s contract. By the time he had gained his temporary release from Vanguard, had signed with Atco, and had flown down to Muscle Shoals, Ala., to cut a new version of the song with Bromberg and producer Tom Dowd, a rival version of the song by New Jersey piano player Bobby Cole had emerged. The two versions battled it out, and the result was two small hits rather than the big hit Walker deserved. The song wouldn’t receive its due until the The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band released theiur cover in 1971. At that time neither Walker´s song, nor their own sweet version of it, was typical of their playlist but I do recall that it not only became a top ten hit for them in the States but was also the version that led me to look and listen more closely to this Gypsy Songman guy.

Mr. Bojangles became the title track of Walker’s first solo album in 1968. it has been described as ´very much a Dylanesque folk album´, as was the follow-up, Vanguard’s Driftin’ Way Of Life in 1969. But Walker was unable to expand the New York buzz around his breakthrough song. He was suffering the same problem as his fellow New York folkies. Everyone was struggling with the fact that folk music’s commercial heart had stopped beating as soon as Dylan plugged in.

Folk music became its own enemy, competing against the memory of the brilliant acoustic stuff Dylan and co. had made in the early sixties and the sound of the future, (a rapidly approaching future at that) of the sonically powerful folk-rock suddenly being made. Psychedelica simply overwhelmed strummed acoustic guitar and a conversational story. James Taylor would solve this problem by marrying his folk music to the Brill Building pop of his new friend Carole King. Emmylou Harris would solve it by joining forces with country-rock pioneer Gram Parsons in L.A. Jerry Walker would solve it by moving to Austin and adding a middle name.

That city was the only oasis for bohemia between New Orleans and Santa Fe. Austin housed The University of Texas and the State Government. There were enough teachers, students, bureaucrats and white-collar workers to support the bookstores, coffeehouses, bars and non-profit groups that are the breeding ground for bohemia. Austin circa 1972 wasa region of hippie culture, a drug-lubricated willingness to try the shock of the new, whether that be music, film, literature, fashion, relationships or even politics. But in the sun-baked environs of Texas, those experiments assumed very different shapes than they did in L.A., Nashville or New York.

Around the sleepy Southern capital, the surrounding hills were still full of cattle and rednecks. In town, zoning barely existed; rents were cheap, and the delicious Mexican and barbecue meals were even cheaper. However, when the Texas legislature had changed the state’s ´blue´ laws to allow alcohol to be sold by the drink, rather than only by the bottle, the college bars along Sixth Street began booking live music, and so did many of the restaurants and halls along the Colorado River.

The gigs didn’t pay much, but musicians could play and develop their sound as they found an audience. Before long, not just singer-songwriters from New York but also country crooners from Nashville, blues guitarists from Dallas, folkies from Houston, rockabilly singers from Lubbock, and Tex-Mex bands from San Antonio were all flocking to Austin. Moreover, they were playing with one another and trading influences back and forth.

According to Mr. Himes, it was in Austin that Walker made the same discovery that would change the careers of dozens of musicians. If you took Dylanesque folk songs and played them with a honky-tonk band, they changed in crucial ways. The two-step rhythms and twangy solos shifted the emphasis from intellectual rigor to working-class pleasures. You could still have literary lyrics, but your subject matter was less likely to address social injustice and personal alienation and more likely to concern drinking, romance, and home.

This didn’t make the songs better or worse, but it sure made them different. For Dylan himself, the venture into country-rock proved a brief detour, for his art was better suited for the confrontational qualities of folk-rock. But for artists such as Walker and Emmylou, whose art was more visceral rather than analytical, country-rock, (now often classified as American) became a career path.

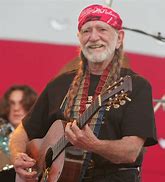

´Our little joke among ourselves,´ Walker told Country Music Magazine in 1994, ´was to say we played country music; we just didn’t know which country it was. But the fact is, I think it’s country music because the subject matter of what you’re talking about is rural. Willie [Nelson] (right) didn’t have a fiddle; Willie didn’t have a steel. But nobody would say Willie wasn’t country.´

The transformation was especially dramatic in Walker’s case, for he went from writing plaintive narrative songs such as Mr. Bojangles and Drifting Kind of Life to such advertisements for Texas hedonism as Hill Country Rain and Hairy Ass Hillbillies. His music developed a swagger, aided rather than hindered by the rough edges left in the arrangements.

The vocals hinted that the world was best viewed as a giant joke, and the instruments played as if they were still learning the song. Other artists mining the same seam in search of a diamond in the coal included Billy Joe Shaver, who passed away recently only a couple of days after Jerry Jeff, Michael Martin Murphey, Willis Alan Ramsey, and Ray Wylie Hubbard. The “Texas Cosmic Cowboy” movement seemed to comprised of only three-name artists !

´I wanted musicians who listened to jazz and blues, some rock and roll, some country, guys with the background to follow me wherever my impulses led,´ Walkers said in his autobiography, Gypsy Songman.

´I was leaning toward a freewheeling, open approach, the sounds born at some late-night party where everybody’s playing and trying new things, and carrying it over to the next day’s rehearsal. This happened constantly in Austin. You’d play all night with different people, trying out new stuff, listening to other people’s new stuff, new ideas begetting more new ideas. You’d greet the dawn with a guitar in your hand and some new songs or licks in your head.´

Within a few months of landing in Austin country-flavored music scene, Walker had enough new songs for an album. He went into a studio that didn’t even have a mixing board with a bunch of local musicians who had never recorded before and cut directly to tape as if it were just one more picking party near the U.T. campus. Though he later had to clean up the tapes in New York, he had nevertheless captured a ´loose as a goose´ spontaneity in his mix of folkie lyrics, blues-rock rhythms and country vocals and solos.

Walker wrote 10 of the dozen songs on the eponymous Jerry Jeff Walker, but the other two came from Guy Clark: That Old Time Feeling and a tune Clark had titled Pack Up All The Dishes. Whilst Walker was mixing the track, though, all the musicians and engineers kept referring to it as that L.A. Freeway song. Finally the singer called the composer and asked if he could re-title it.

the journalist´s summation of the final recorded version of that song is informative.

He suggest that ´If the verses had the conversational tone of Walker’s folkie past—though his acoustic guitar picking is bolstered by organ and drums—the chorus is the kind of rousing sing-along more suited for a sawdust saloon than a campfire or picket line. As the pedal-steel guitar comes swooping in along with a cranked up electric guitar and haphazard harmony vocals, Walker belts out, “If I can just get off of this L.A. Freeway without getting killed or caught, I’ll be down the road in a cloud of smoke.” And on the instrumental coda, the female gospel singers, wailing harmonica and soloing guitar suggest what that trip down the highway might feel like.´

L.A. Freeway was the first single off Walker’s first Decca/MCA album and though it didn’t chart, it stirred up quite a bit of interest on underground FM stations of the day. It was a milestone track, for it alerted country-rock fans around the nation that Texas had come up with an original twist on the country-rock model. It transformed Cosmic Cowboy Music from a local scene into a national phenomenon. It established Walker as a cult figure and made his more devoted fans intrigued about this previously unrecorded songwriter named Guy Clark.( a man I was fortunate enough to interview several times on his UK tour and who has featured many times on our pages here at Sidetracks & Detours: check out our archives):

photo by Alan Messer

And soon Walker was doing the same for other Texas songwriters who became favourites of this magazine, such as Rodney Crowell, The Flatlanders’ Butch Hancock, Ray Wylie Hubbard, Billy Joe Shaver, Gary P. Nunn, and Lee Clayton. Walker, who had set out to become the next Bob Dylan, was now more akin to Emmylou Harris. He was a similarly interpretive singer to her and shared her ability to spot obscure song-writing gems and bring them to a broader public with his charismatic vocals. If Harris did that with songbird purity, Walker did it with well-lubricated party spirit. But each in their own way sparked a major branch of alternative country music. (that is now so often placed under the umbrella of American !)

It might be true that Walker never had a hit-single record under his own name, but between 1975 and 1978 he did put four albums in the top-25 of Billboard’s country charts. That’s pretty damn impressive. By 1980, however, Walker had lost his mojo. The partying-cowboy schtick had grown thin; his own song-writing had grown repetitive, and the songwriters he’d relied on had careers of their own to take care of.

Walker is sometimes called the ´Jimmy Buffett of Texas,´ even though Walker released his first Texas album, Jerry Jeff Walker, in 1972, a year before Buffett released his first Florida album, A White Sport Coat and a Pink Crustacean. The two men had been friends in New Orleans, and had even wrote the song Railroad Lady together.

Mr. Himes concludes his piece by suggesting that both Jerry Jeff and Jimmy built large followings in the seventies with a beguiling mix of the sensitive and the rowdy. But once the sensitivity became maudlin and the rowdiness self-indulgent, the charm wore off for both of them.

That final sentence seems slightly damning, and sounds harsh to me of artists who dealt us songs like Mr. Bojangles and Son of A Sailor that have endured to this day and will do to one hundred years from this day.

Matt Schudell, writing in the The Washington Post to commemorate Jerry Jeff´s death and to celebrate his life, recalls the story of how Jerry Jeff Walker met the subject of his most famous song whilst in jail. This was merely one of several sleep-it-off-and-pay-your-fine experiences in those days for Jerry Jeff but on this occasion he woke to hear his cell mate telling him his life-story. His fellow prisoner was an an old man who was, by then a homeless street dancer, who had once performed at ´minstrel shows and country fairs throughout the South.

photo 14 Jerry Jeff Walker was singing in New Orleans coffeehouses and on street corners in 1965, when he was thrown in jail for public intoxication. It wasn’t the first time he had been drunk, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last, but as he sobered up, he heard his cellmate tell him a story that would change his life.

He was an old man with years of sorrow behind him, a homeless street performer who had once been a dancer ´at minstrel shows and county fairs throughout the South.´

Like Jerry Jeff, he didn’t use his real name, but instead called himself Bojangles, after Bill Bojangles Robinson, a renowned vaudeville and film dancer who died in 1949.

Mr. Walker used the encounter as the basis for his song “Mr. Bojangles”:

However, it was only after The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band recorded a version of Mr. Bojangles that reached No. 9 on the Billboard pop chart in 1971, that the song became recognized as a standard and was subsequently recorded by artists as varied as Nina Simone, Harry Belafonte, Dolly Parton, Bob Dylan, Whitney Houston and George Burns.

It would have been around this time that I, and probably all readers of this articles, saw incredible tv footgage of Sammy Davis Junior not only singing the song in a hearetfelt fashion but also performing a street dance whilst doing so, complete with injected mis-steps. It was a pice of film that matched Singing In The Rain or Puttin´On The Ritz, even, such was the sense of gravitas about is.

He had complications from throat cancer and other ailments, said his wife, Susan Walker.

In 1973, he and his band released the album Viva Terlingua, which has influenced generations of country and roots musicians, from Lyle Lovett and Steve Earle to Lucinda Williams and Robert Earl Keen. Recorded in the virtual ghost town of Luckenbach, Tex., Viva Terlingua practically defined the new Texas sound, combining elements of country, rock and folk music with a touch of sagebrush poetry.

Mr. Walker contributed five songs to the album, including “Wheel,” a heartfelt ballad about the death of his grandfather. The best-known songs, though, were by other writers, including Guy Clark’s cinematic Desperados Waiting for a Train, Ray Wylie Hubbard’s honky-tonk anthem, Up Against The Wall Redneck Mother and Gary P. Nunn’s London Homesick Blues, about a Texan stranded in England who longs “to go home with the armadillo, good country music from Amarillo and Abilene.”

By end of that decade, though,, Mr. Walker’s life of constant excess was catching up to him. He owed hundreds of thousands of dollars in unpaid taxes, and his second marriage was about to fall apart. He cut back on the drugs and drinking and took up exercise, often bicycling with his children. Instead of traveling with an entourage on a private jet, he gave solo performances in small, intimate settings.

´I did set out to be a little notorious,´ he told the Houston Chronicle in 2005. ´I always thought that people would be interested in my music if I appeared to be an interesting person.´

Jerry Jeff Walker, who performed at the 1993 inauguration of President Bill Clinton, released more than 30 albums, the most recent of which was It’s About Time in 2018.

One of his proteges, singer-songwriter Todd Snider, recalls a night when he and Jerry Jeff were the last customers at a bar in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

After it closed, they were walking down a street at 2 a.m. when they heard someone play the opening chords to Mr. Bojangles on a banjo.

´This was a bedraggled guy, not a kid,´ Snider wrote in his book, wonderfully entitled I Never Met a Story I Didn’t Like. ´(He was) a homeless guy, kind of crazy looking, with a harmonica around his neck, his hat on the ground in front of him, and nothing in the hat . . .

The guy looked up at us. He didn’t know Jerry Jeff Walker was standing there. He may never have even heard of Jerry Jeff Walker´

They listened as the man sang Walker’s masterpiece about a down-and-out street performer, ´and I could feel us both getting choked up,´ Snider wrote.

He wondered if he should say something: ´but no, I figured if Jerry Jeff wanted to let the guy know who he was, he’d tell him.´

The only thing Jerry Jeff Walker Walker said was: ´That sounded great.´

He took all the money out of his pockets, put it in the street singer’s hat, then walked away.

He never told him his name.´

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!