ARTS & SCIENCE & EDUCATION FOR ALL CAN SAVE THE WORLD

ARTS & SCIENCE & EDUCATION FOR ALL CAN SAVE THE WORLD

by Norman Warwick

Engaging with art is essential to the human experience. Almost as soon as motor skills are developed, children communicate through artistic expression. The arts challenge us with different points of view, compel us to empathize with ´others,´ and give us the opportunity to reflect on the human condition. Empirical evidence supports these claims: Among adults, arts participation is related to behaviours that contribute to the health of civil society, such as increased civic engagement and greater social tolerance. Yet, while we recognize how the arts benefit out mental well being and their restorative powers and ability to nurture the soul we so rarely think as an economic game-changer and in fact rarely even does education seem to think of them as a career path.

A 2019 paper published by Brian Kisida, Assistant Professor, Truman School Of Public Affairs at The University of Missouri and Daniel H. Bowen, Assistant Professor, College Od Education And Human Development at Texas A & M University confirmed art´s transformative capacities and questioned, why, therefore the arts have only such a tenuous hold in most sectors in the USA.

Dr. Kisida (left) is an Assistant Professor in the Truman School of Public Affairs at the University of Missouri. He has over a decade of experience in rigorous program evaluation and policy analysis. He has extensive experience conducting randomized controlled trials and has co-authored multiple experimental impact evaluation reports through the Institute of Education Sciences at the U.S. Department of Education.

The dominant theme of his research focuses on identifying effective educational options and experiences for at-risk students that can close the achievement gap, the experience gap, and the attainment gap. His research has examined the educational benefits of cultural institutions, school-community partnerships, art and music education, teacher diversity, urban charter schools, school integration, and the cognitive and non-cognitive effects of means-tested urban scholarship programs for at-risk students. Increasingly, his research agenda has evolved toward examining policy outcomes broader than student achievement on standardized tests, such as non-cognitive outcomes, cultural and social capital, student engagement, civic outcomes, and long-term educational attainment. His academic publications include articles in the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Sociology of Education, Educational Researcher, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, Economics of Education Review, Policy Studies Journal, School Effectiveness and School Improvement, and Education and Urban Society.His work has been cited in congressional testimony before the U.S. House and Senate, and it has appeared in numerous media outlets, including The New York Times, USA Today, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and CNN.

The Brown Center Chalkboard launched in January 2013 as a weekly series of new analyses of policy, research, and practice relevant to U.S. education.

In July 2015, the Chalkboard was re-launched as a Brookings blog in order to offer more frequent, timely, and diverse content. Contributors to both the original paper series and current blog are committed to bringing evidence to bear on the debates around education policy in America.

Check out https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/

A critical challenge for arts education, said Kisida and Bowen, has traditionally been a lack of empirical evidence that demonstrates its educational value. Though few would deny that the arts confer intrinsic benefits, advocating ´art for art’s sake´ has been insufficient for preserving the arts in schools—despite national surveys showing an overwhelming majority of the public agrees that the arts are a necessary part of a well-rounded education.

Over the last few decades, the proportion of students receiving arts education has shrunk drastically. This trend is primarily attributable to the expansion of standardized-test-based accountability, which has pressured schools to focus resources on tested subjects. As the saying goes, what gets measured gets done. These pressures have disproportionately affected access to the arts in a negative way for students from historically underserved communities. For example, a federal government report found that schools designated under No Child Left Behind as needing improvement and schools with higher percentages of minority students were more likely to experience decreases in time spent on arts education.

Browncenter Chalkboard conducted, and published in 2019, the first ever large-scale, randomized controlled trial study of a city’s collective efforts to restore arts education through community partnerships and investments. Building on their previous investigations of the impacts of enriching arts field trip experiences, this study examines the effects of a sustained reinvigoration of school-wide arts education. Specifically, the study focussed on the initial two years of Houston’s Arts Access Initiative and includes 42 elementary and middle schools with over 10,000 third- through eighth-grade students. All that was made possible by generous support from the Houston Endowment, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Spencer Foundation.

Due to the program’s gradual rollout and oversubscription, they implemented a lottery to randomly assign which schools initially participated. Half of these schools received substantial influxes of funding earmarked to provide students with a vast array of arts educational experiences throughout the school year. Participating schools were required to commit a monetary match to provide arts experiences. Including matched funds from the Houston Endowment, schools in the treatment group had an average of $14.67 annually per student to facilitate and enhance partnerships with arts organizations and institutions. In addition to arts education professional development for school leaders and teachers, students at the 21 treatment schools received, on average, 10 enriching arts educational experiences across dance, music, theatre, and visual arts disciplines. Schools partnered with cultural organizations and institutions that provided these arts learning opportunities through before- and after-school programs, field trips, in-school performances from professional artists, and teaching-artist residencies. Principals worked with the Arts Access Initiative director and staff to help guide arts program selections that aligned with their schools’ goals.

Browncenter Chalkboard´s research efforts were part of a multi-sector collaboration that united district administrators, cultural organizations and institutions, philanthropists, government officials, and researchers. Collective efforts similar to Houston’s Arts Access Initiative have become increasingly common means for supplementing arts education opportunities through school-community partnerships. Other examples include Boston’s Arts Expansion Initiative, Chicago’s Creative Schools Initiative, and Seattle’s Creative Advantage.

Messrs. Kisidi and Bowen reported that ´through our partnership with the Houston Education Research Consortium, we obtained access to student-level demographics, attendance and disciplinary records, and test score achievement, as well as the ability to collect original survey data from all 42 schools on students’ school engagement and social and emotional-related outcomes.

We find that a substantial increase in arts educational experiences has remarkable impacts on students’ academic, social, and emotional outcomes. Relative to students assigned to the control group, treatment school students experienced a 3.6 percentage point reduction in disciplinary infractions, an improvement of 13 percent of a standard deviation in standardized writing scores, and an increase of 8 percent of a standard deviation in their compassion for others. In terms of our measure of compassion for others, students who received more arts education experiences (were shown to be) more interested in how other people feel and were more likely to want to help people who are treated badly.

When we restrict our analysis to elementary schools, which comprised 86 percent of the sample and were the primary target of the program, we also find that increases in arts learning positively and significantly affect students’ school engagement, college aspirations, and their inclinations to draw upon works of art as a means for empathizing with others. In terms of school engagement, students in the treatment group were more likely to agree that school work is enjoyable, makes them think about things in new ways, and that their school offers programs, classes, and activities that keep them interested in school. We generally did not find evidence to suggest significant impacts on students’ math, reading, or science achievement, attendance, or our other survey outcomes, which we discuss in our full report.´

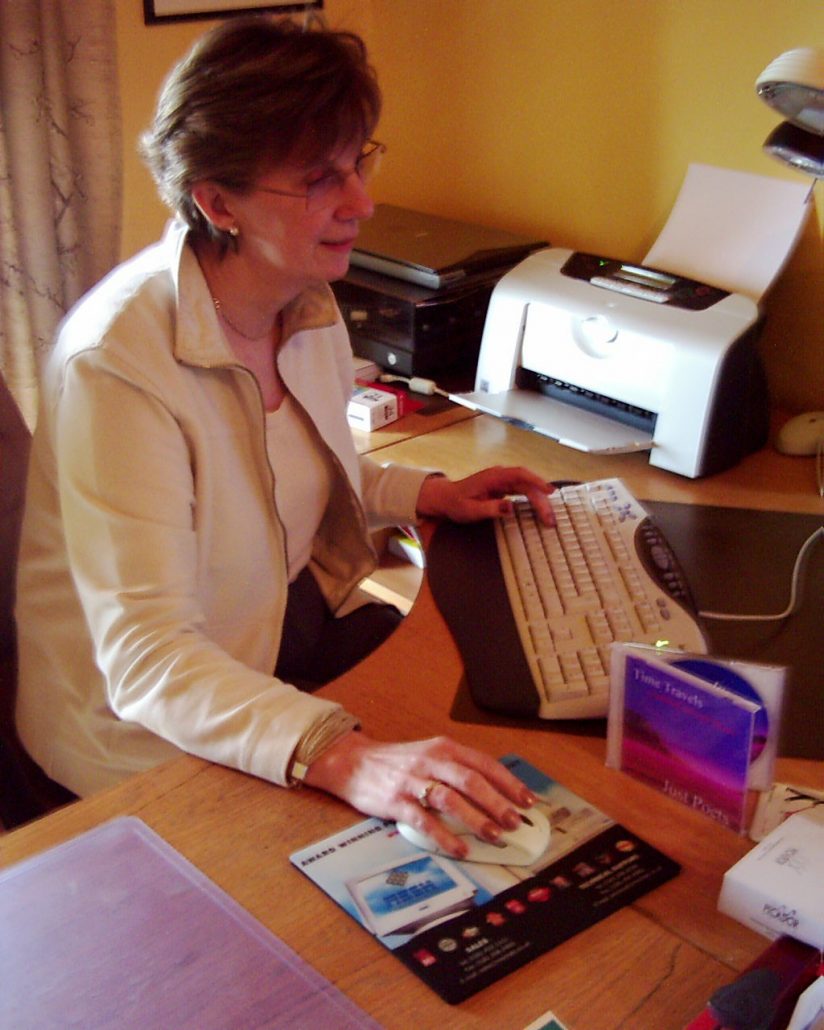

founder member of Just poets

with Norman Warwick

As education policymakers increasingly rely on empirical evidence to guide and justify decisions, advocates struggle to make the case for the preservation and restoration of arts education. To date, there is a remarkable lack of large-scale experimental studies that investigate the educational impacts of the arts. One problem is that U.S. school systems (and certainly UK schools at the time I and my Just Poets partner, Pam McKee, were peripatetic facilitators in schools in the UK a few years ago) rarely collect and report basic data that researchers could use to assess students’ access and participation in arts educational programs. Moreover, the most promising outcomes associated with arts education learning objectives extend beyond commonly reported outcomes such as math and reading test scores. There are strong reasons to suspect that engagement in arts education can improve school climate, empower students with a sense of purpose and ownership, and enhance mutual respect for their teachers and peers. Yet, even as educators and policymakers have come to recognize the importance of expanding the measures bodies such as Browncentre Chalkboard use to assess educational effectiveness, data measuring social and emotional benefits are still not widely collected. Future efforts should continue to expand on the types of measures used to assess educational program and policy effectiveness. This lack of empirical date that could build empirical evidence of positive impact is also required (quite rightly) by prospective funders and the lack of acquisition and provision of such evidence created difficulties in schools and community arts private funding.

Browncentre Chalkboard´s findings provide strong evidence that arts educational experiences can produce significant positive impacts on academic and social development. Because schools play a pivotal role in cultivating the next generation of citizens and leaders, it is imperative that we reflect on the fundamental purpose of a well-rounded education. This mission is critical in a time of heightened intolerance and pressing threats to our core democratic values. As policymakers begin to collect and value outcome measures beyond test scores, we are likely to further recognize the value of the arts in the fundamental mission of education.

Throughout the several years we worked together as the sing writer duo, Lendanear, Colin Lever was a secondary school science teacher. He was passionate about three aspects in particular, but not necessarily in this order: his subject matter, the benefits of a good education, the opportunities a good education provides. That his students have the same opportunities afforded to them as those at other schools was always important to Colin.

He retired from the chalk-face of the classroom a long time ago and now lives on Jersey as a journalist working as an independent educational commentator.

On his blog he says, ´Education is now principally about meeting targets. It is no longer about what the school can do for the child but what the child can do for the school. The system is divisive, with almost half (those who don’t get the required passes) disenfranchised and disaffected. Mental health issues have increased as a consequence. The most vulnerable in society are marginalised. Education does not put the needs of the child first and my mission is to not only expose this fact but also to show also that there is a way forward with education that is not exclusive but inclusive.´

I was interested, therefore, in the November 3rd edition of the Jersey Evening Post to read his reaction to a recently published report. I well remember that although Colin experimented in the science laboratory whilst I dabbled in the art room, we both wanted education to provide opportunity for all children.

The headline of the piece (far longer than those we employ here at Sidetracks & Detours) asked the pointed question, Will Our Leaders Have The Appetite To Take A Serious Look At How Education Is Funded In The Island (of Jersey)?

The headline framed Colin´s questioning of the recent publication of The Independent School Funding Review, a report that Colin claims has highlighted a huge gulf in society, — one which is magnified by the island´s education system.

The introduction to the article went on to say that low attainment is synonymous with poverty, but argues that doesn´t need to be the case.

Colin wrote that when reading the Independent School Funding Review report he had to search to find something positive about the management of Jersey’s education system. He noted that the report implied that education is under funded, governance is poor, special educational needs (SEN) provision lacking.

Examination results were pulled apart in the report, Colin suggested, despite the fact that attainment appears to have improved. Inequality in Jersey´s education system is highlighted, along with teaching prowess and underfunding of vocational education post-16. The report gives a fifteen point plan, and a ball-park figure of £11.6m to put things in order. Whilst the document is essentially about fiscal matters, what it recommends is a radical overhaul.

Colin points out, though, that in the middle of a pandemic that has already led to a borrowed £336m., this year, rumours abound that taxes will have to rise and that another period of austerity is likely.

´Whilst £3million per annum would not be seen as excessive under normal circumstances,´ he asks, ´in our present fiscal situation will the government match the request pound for pound?´

The document states that the average expenditure per child in fee-paying secondary schools (£69k p.a) is significantly higher than that in non-fee paying schools (£60k p.a). It suggests that parents of children that attend fee paying schools could be means tested.

´Call me cynical,´ says Colin (he is, and in this case so am I) ´but every time any government minister has tried to alter the status quo in respect of monies allocated to the private sector they have found themselves out of a job.´

It is political suicide, he suggests, to even attempt such a move, bearing in mind there is an election in 2022! Factor in the number of civil servants to whom these schools are their alma mater.

Colin writes that ´The document sets about trying to put our education system on a more equitable footing. In order to do so it proposes to apply increased financial resources to those most in need. The report points out that no extra allocation is given to schools on Jersey for pupils that have English as a second language or those with low attainment. State schools have to shoulder over 95% of the burden without any extra resources. The report recommends that formula funding be altered to account for these discrepancies. This would be on top of any allocation from Jersey Premium.´

Colin cites one educational arena on the island, that of Highlands College, ´that has been the Cinderella of post-16 education.´ The report states that each student at Highlands receives £1,100 less p.a. than those at Hautlieu. It suggests a merger between the two and to reduce 11-16 state schools to three. There will be significant parental/political opposition to any changes to the 14-16 system.

The ISFR also recommended a review of inclusion, which Colin calls ´yet another educational Cinderella that is conveniently swept under the carpet.´ To tackle this issue properly, he predicts, will be expensive and is not included in the £11.6million recommended.

There is now a push for free school meals for the most vulnerable.

´If successful,´ Colin wonders, ´how likely that this will come out of the education budget?´

In respect of professional support for pupils the report recommends;

“Strengthen the central education team so that all children have access to specialist help when they most need it.” It suggests increasing educational psychology provision by 33%. Under Onegov changes, three heads of service for Inclusion have recently resigned and the advert for a new Head of Inclusion led with the following statement: “We need to be clear from the outset. On the island of Jersey we haven’t done enough for vulnerable children over too many years.”

Colin says this is ´a shocking admission, albeit an accurate one.´

Colin summarises the report by saying

´What the ISFR has highlighted is the huge gulf in island society, one which is magnified by our education system. Low attainment is synonymous with poverty but it need not be if we build a ‘world class’ education system. The thread running through the ISFR is one of neglect, neglect of any pupil/student that does not fit the narrow criteria of attaining high grades in flagship examinations. The financial bias and by default, most resources, continue to be directed at the academic/fee paying sector. Those in charge will, no doubt, hide behind the excuse that they have been consistently underfunded and have had to prioritise. While there is some truth in this, their inertia cannot just be down to fiscal restraints. Propping up fee´-paying schools is a political decision, marginalising SEN is an ideological decision, ignoring post-16 vocational work is both and maintaining a dysfunctional funding formula is simply poor governance.

There are those in authority that suffer from ideological myopia, seeing the needy as either deserving or undeserving. The Education Minister assured us on social media that the report would be ‘acted on’. Expect the recommendations to be diluted until they are of as much use as a homeopathic remedy.

As long as I have known him Colin Lever has attacked, like a bulldog, any educational propositions that further privilege the elite whilst continuing to dislocate the already disillusioned and disenfranchised.

I cannot claim to know enough about the education system, particularly on Jersey, as I have only ever been part of UK education system as a peripatetic visitor delivering arts related workshops, but I can nevertheless see that Colin´s doubts expressed above are well argued, seemingly well founded and certainly well-intended.

Whether in the humanities or the sciences the world is going to need invention and creativity, and given that necessity is the mother of such invention then abandoning those in need would seem short sighted as well as cruel.

Not all scientific inventions and medical discoveries have been made by the children of those wealthy enough to pay for a private education and some of the world´s greatest works of art have been produced by the LS Lowry´s of this world. The world, in the generations ahead may need medicine more than ever and it may need music, too. It will need science and song, alchemy and art and firmness and fairness.

To help ensure that, the next generation must be fully educated. An education system delivering flagship subjects to a perceived elite core will not only fail a generation but also will ensure that generation in turn fails the world. We will need our draftsmen as well as our dreamers, artisans and artists and the next generation of students ALL need to be given an education that will offer them choices and opportunities as to how best they want to, and are able, to serve the world.

Engaging with art, we are told, is essential to the human experience. Almost as soon as motor skills are developed, children communicate through artistic expression.

The findings from BrownCentre Chalkboard in 2019 and the text (and sub-text) of the 2020 Independent School Funding Review from Jersey, the impassioned response of former educators like Colin Lever and the past experience of peripatetic artists in schools, such as my own Just Poets, provide strong evidence that arts educational experiences can produce significant positive impacts on academic and social development.

Schools have to play a pivotal role in cultivating the next generation of citizens and leaders, so it is imperative that, as we slowly overcome Covid and its mutations, we as a species reflect on the fundamental purpose of a well-rounded education. This mission is critical in a time of not only terrifying health threats but also heightened intolerance and pressing threats to our core democratic values. We must present our policymakers with empirical evidence from collected data of important outcome measures beyond test results to demonstrate that the arts have an important contribution to make.

When we then learn to properly evaluate, we are likely to further recognize the value of the arts in the fundamental mission of education, and together the sciences and the arts might just save the world !

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!