CHANGING NATURE OF PROTEST IN JAZZ

CHANGING NATURE OF PROTEST IN JAZZ

by Norman Warwick

Melvin Gibbs is a jazz man through and through; a bass player, composer and producer with a proud forty year career to show for it. He recently stood at the site of the George Floyd Memorial in Minneapolis, (where he took the photograph that covers this piece) and began to ponder on how the role of jazz music and the wider jazz community has evolved in the fight against racial injustice.

The area is becoming something more than a place of remembrance, perhaps. it is becoming a location of hope. Douglas Ewart regularly plays live music at the site and has been joined by a fluid ´band´ line-up over the months.

´We went to offer a positive notion,´ he told Melvin Gibbs, ´a positive offering, a positive spirit. Some of the music, of course, expresses both joy and pain. You know, you can´t stand at that site and divorce yourself from that and not have that part of the painful aspect in your consciousness.

We can´t just stand there, with that pain, though. We have to be getting up. Getting up because we know that there was the fight and the survival. That fight has been endemic to our people. What has always made us strong is that, no matter what has happened, our people always find a way to move forward.´

Mankwe Ndosi It was on Saturday 30th May, only a few days after George Floyd´s death that hundreds of people gathered in Powdethorn Park, not far from where the infamous incident had taken place. Reportedly, they were all socially distancing as they paid respect to Floyd. Amongst them were Douglas Ewart, who is a multi-instrumentalist, and social worker and vocalist composer Mankwe Ndosi, and the two played music to the crowd, as a duo.

Ndosi has since said that what they did couldn´t really be called a performance. He considered what they did was to become hunter-gatherers and energise people before the hunt, before they had to rise to address a challenge.

´The nature of the atrocity was that a man had been killed by those who we, as citizens of Minneapolis pay to protect us,´ he states. ´This atrocity was another example, albeit an extreme one of the abuse that black people, poor people, go through on a regular basis. Because of the reaction the police were gone one way or another. I can´t say why. That was the weekend when white people realized, and leaned into the idea, that the police don´t protect you.´

Ewart is a President Emeritis of the Association For the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) nd so is well aware of the long and fruitful connection between social protest and the musical genre we call jazz. He is aware of how that partnership, and jazz alone, can express itself.

´The protest, or the demand,´ as he prefers to say, ´comes out of the content of what´s done, you know, the things we sing about, our approach to playing, the fact that we defined what it is we felt, was an experience.´

His preference for the word demand rather than protest makes sense, he says, given that from the stage at Carnegie Hall in 1912 to the streets of Minneapolis in 2020 jazz has always ´demanded.´

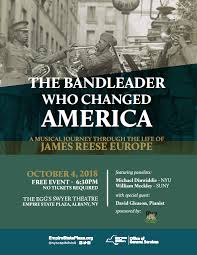

Jazz does not, however, always protest in the same way. When James Reese Europe and his 125 piece Clef Clu Orchestra made its debut at Carnegie Hall, billed as the first syncopated ´music ´group to play there the band leader did not really voice his demands. His music was neither delivered, nor received, as overt ´protest´ music.´ Nevertheless, the very fact of its existence made a demand in the context of the times and the zeitgeist of its presentation. It seems highly likely that the musicians would have been very aware of the impact their delivery would have on those cultures that opposed it. It is probably safe to assume that James Reece Europe would agree if he heard Ewart saying today that ´we´ve always had to be ingenius about how we set the terms of engagement.´

For the jazz musicians who came of age in the time of ´The Red Summer´ and ´The Tulsa Massacre´ those terms had to be very different. The kind of open public demonstrations against racism and violence that we´ve seen over the past few months in Powderhorn Park and around the world were not, then, a reality. ´

Wikipeadea reminds us that the term Red Summer was coined by civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson, who had been employed as a field secretary by the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) since 1916. In 1919, he organized peaceful protests against the racial violence which had occurred that summer. In most instances, attacks consisted of white-on-black violence. However, numerous African Americans also fought back, notably in the Chicago and Washington, D.C. race riots, which resulted in 38 and 15 deaths, respectively, along with even more injuries, and extensive property damage in Chicago.

Still, the highest number of fatalities occurred in the rural area around Elaine, Arkansas, where an estimated 100–240 black people and five white people were killed—an event now known as the Elaine massacre.

The anti-black riots developed from a variety of post-World War I social tensions, generally related to the demobilization of both black and white members of the United States Armed Forces following World War I; an economic slump; and increased competition in the job and housing markets between ethnic European Americans and African Americans. The time would also be marked by labour unrest, for which certain industrialists used black people as strike-breakers, further garnering the resentment of white workers.

The riots and killings were extensively documented by the press, which, along with the federal government, feared socialist and communist influence on the black civil rights movement of the time following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. They also feared foreign anarchists, who had bombed the homes and businesses of prominent figures and government leaders.

The same source tells us that The Tulsa Massacre, also referenced by Ewart, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1921, when mobs of white residents, many of them deputized and given weapons by city officials, attacked black residents and businesses of the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It has been called ´the single worst incident of racial violence in American history.´ The attack, carried out on the ground and from private aircraft, destroyed more than 35 square blocks of the district—at that time the wealthiest black community in the United States, known as ´Black Wall Street.´

It was Duke Ellington who probably best encapsulated the artistic spirit of his time when he wrote in in 1931 that ´what we could not express openly, we expressed in music.´

´Taking The Knee´ a gesture of solidarity in sport has been a restrained and dignified yet defiant posture since Floyd´s death but even that has suffered from the thought the Black Lives Matter movement have been commodified and misappropriated by bodies with different agendas. So Ewart´s ´jazz protest´ sessions might be the strongest of reminders, as if any were needed, about the apparent callousness of the killing of George Floyd

As a footnote to this story there is press speculation that the trial of the policeman accused of killing George Floyd, might be shown ´live´ on tv here in the UK. What effect that might have on fairness and lawfulness and protest and demand, though, is surely a matter of conjecture.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!