BEWARE A GEEK BEARING GIFTS

BEWARE A GEEK BEARING GIFTS

By Norman Warwick

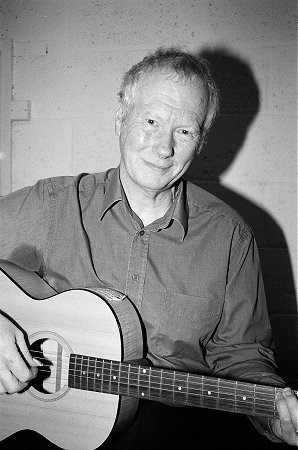

Over the last four decades or so I collected about fifty albums by two particular singer-writers, John Stewart and Townes Van Zandt. It has all been the fault of Pete Benbow, a singer guitarist who so impressd me when he introduced me to the arts through his own musical interpretations of their work. Because of him I started collecting (in a scholarly collector´s fashion, not in any geek-ish way) and subsequently interviewed John Stewart, an American artist formerly of The Kingston Trio, on half a dozen occasions. Over the same period I came to know Townes pretty well, too. He was a singer from Austin, Texas and I also interviewed him on several occasions. Thank goodness, though, I never became some stage-door Joe hanging around trying to catch a word from my heroes. No, no. Instead I became a reporter and music critic,….hanging around like a stage- door Joe trying to catch a word from my heroes.

I am now of the opinion that one of these artists, John, was a great songwriter, whilst Townes was a writer of great songs. It is a subtle, but important difference. Neither ever achieved any real commercial success in the UK although The Monkees had a massive hit with John´s Daydream Believer.

I used to love The Monkees TV show on Saturday evenings (despite the fact that when I watch re-runs these days I can make no sense of the ´plot´ I do still love the soundtracks). It was a week-end ritual for mum and dad to drive sixty miles from Rochdale to Tadcaster every Saturday afternoon to see my grandparents and we would invariably arrive just in time for me to dash from the car into Nan´s unused posh front room of their council house and turn on the telly to watch the antics of The Monkees. As a young teen I was beginning to shape my musical tastes and although The Monkees were much maligned amongst my schoolmates who were maturing with The Rolling Stones or The Beatles, I began to note the quality of the song-writing of the band´s woolly hatted member, Mike Nesmith, in amongst the great writers like Neil Diamond, who were supplying the group´s singles. Nesmith would go on to ´invent´ MTV and release a body of his own impressive songs for many years after The Monkees split up. He had a reverence for authentic country music that is evident throughout the dozen or so albums of his I eventually accumulated. Was it Geek-ish to be so chuffed that alphabetical proximity allowed the albums of The Monkees to be filed in a view in which they could always be seen in the same vista as Nesmith? No, just keeping the house in order.

There was a similar affinity, too between John Stewart, who also wrote for the Monkees, and The Kingston Trio of which Stewart was once a member. Judiciously filed, my collections of their thirty albums and his more than fifty titles also stood close together on my shelves.

The whole chronology of my early childhood awareness of The Kingston Trio, and subsequently then with John Stewart, is difficult to disentangle.

I first became aware of the Kingston Trio when I was about six or seven years old. Hang Down Your Head Tom Dooley is a song that I later came to learn is a traditional folk song recorded by scores of artists in many different styles, ranging from the sublime to the ridiculous.

My dad´s version, that he sang in the car all the time as he drove me to school every morning was at the sublime end of the scale, and the song was high in his repertoire, in an eclectic mix that included all of Sinatra (it seemed to me), Perry Como and Mel Tormé. He could also throw in some Sara Vaughan and bits of Bing Crosby. My dad was singing The Great American Songbooks, volumes 1 to 100, long before Rod Stewart had ever heard of America. Dad´s voice and song preferences were the soundtrack to my formative years, and he would occasionally even include contemporary pop of the era. I remember him singing Till There Was You in a Beatles-ish way and he was very keen on Peter Sarstedt´s Where Do You Go To My Lovely? Dad had a great voice and he and my Uncles Sid (my step-grandfather) would often be the lead voices of the drunken choir in spit and sawdust pubs from York to Manchester, before tumbling out on to The Street Where You Live.

How dad ever came to know all these songs I´ll never understand, and I´m ashamed to say I never asked him. Until well into my teens we didn´t have a record-player in the house, nor even an on-switch on the radio as I recall. I remember getting home from cubs at round about nine o clock on Wednesday night when The Perry Como Show was just flickering to life on our black and white TV.

So, The Kingston Trio´s Tom Dooley was an eccentric inclusion even on a song list as long as my dad´s, but it was probably one of the very first songs of which I learned the lyrics. I can´t even recall how I knew it was by The Kingston Trio, and I´m sure that dad had no idea. I realise now that the group had a hit with the song even in the UK at round about that time and that Lonnie Donegon, too, skiffled it up the pop charts but unless memory tells lies, my dad used to sing what I later came to identify as the Trio version.

Four or five years later I learned the name of John Stewart when The Monkees recorded Daydream Believer. We had, by then, acquired a family record player, or gramophone as it was then called, and we could get the Light and Home services on its radio. One (Sunday?) afternoon I was listening to Family Favourites while mum was doing the ironing. Dad staggered in from slurring his songs down at The Coach And Horses and asked mum whether his beef, Yorkshire pudding and roast potato dinner was ready. It was and had been, as it was habitually on Sunday lunch times, ready a couple of hours earlier, for the precise time he had promised to be home. As she bustled to the kitchen to ´plate it up´ for him, mum leaned across to switch off the radio just as that short instrumental burst opened a playing of Daydream Believer.

´No, schtop, let´ch áve a lishen. I like thith schong,´ said dad, of a release that had by then been in the charts for about six weeks. I loved the Monkees and loved that song and a recommendation from dad moved them even further into my own hall of fame.

Months, maybe years, later Noel Edmonds´ Sunday morning programme (left) had become my required listening on our posh teak-veneered, sliding door cabinet music system. Suddenly I heard Daydream Believer but in a totally different version from that of Davy, Mickey, Michael and Peter. The song had been attracting cover versions by the likes of Anne Murray, but this was a deep voiced invitation to Sleepy Jean to cheer up. As I listened to this new version I silently applauded Noel Edmonds for playing something different, for in my head, as a sign of my growing maturity, I secretly now felt that Davy´s shakers were a bit naff and the instrumentation of their Daydream Believer was somewhat overblown.

Edmonds had to forfeit the house-points I had given him though, when he prattled away at the end of the record about yes, he knew it was not great and hardly recognisable ´but this guy, John Stewart, can do what he wants with the song because he wrote it.´

That seemed to me to be damning John Stewart´s version of his own song with faint praise and I would later find out that the same had happened to him throughout his career in The Kingston Trio because he had replaced founder and fans´ favourite Dave Guard and suffered by prejudiced comparison,

I searched all over for this John Stewart version, even picking up his albums in search of it, but it would be another forty years before Stewart recorded Daydream Believer with Nanci Griffith. From those initial albums I bought, though, I did learn from the sleeve notes about Stewart´s time with The Kingston Trio and how often he took lead vocals on ´their´ song, (actually in the public domain), Tom Dooley. Main Roads for alphabetical and Sidetracks & Detours for circuitous coincidence, eh?

So now my full discography of John Stewart sits near Townes Van Zandt, ….¨Farther Along´ than The Byrds (with and without Gram)…. and of Gram, solo, with Emmylou and with The Flying Burrito Brothers,….and I have everything The Flatlanders ever recorded as well as all the solo albums of all the major individual members like Butch Hancock and Joe Ely and Jimmy Dale Gilmore, all courtesy of ´The Lawnmower Man.’

Insert photo 6 The Flatlanders This charming, smiling fount of all musical knowledge was so called by record collectors all over the UK because he sold rarities and collectable to visitors to a village council house in Wales. That those visitors might not have known they needed them, let alone wanted them was not an issue, and that he advertised himself, to the general public and to Her Majesty´s Inland Revenue Service as an occasional repair-man of gardening tools, mattered very little to such visitors. I would make a once a week round trip of more than 150 miles to his home, in which every downstairs room, including the kitchen, was lined from floor to ceiling with shelves of thousands of albums.

I stocked up as quickly as I could with John Stewart´s back-catalogue but was led down further sidetracks and detours and expense accounts into collections of Kingston Trio albums and releases by other artists who had recorded with John Stewart, like his wife, the wonderful Buffy Ford.

The Lawnmower Man also introduced me to the likes of the then present-day Loggins and Messina almost all the way back to where it all began with The Carter Family. The five or six years during which I used to visit North Wales were a prolific period in the growth of my album collection.

Following that I seemed to become a hunter and gatherer of quite a few Chip Taylor albums over the years, too.

It was a guy called Phil Gallagher from the Wirral, who introduced me to the music of Chip Taylor, another American artist. You might not have heard of him, either, but I now have more than thirty albums by this guy.

He not only wrote Angel Of The Morning, a global hit, but also wrote Wild Thing and With A Girl Like You recorded by The Troggs, as well as I Can´t Let Go, a massive top ten hit for The Hollies.

Phil lent me a third or fourth generation cassette recording of Chip´s album, Last Chance, and on that was a song called I Want The Real Thing in which Chip listed all the seminal moments of rock and some of the occasions when the spirit of rock had been diluted to non-alcoholic. That one song alone became responsible, at the last count, for more than 500 albums in my archives, by the likes of artists such as Hank Ballard, who might have much more claim to have invented the Twist than had Chubby Checker. Also his ubiquitous Annie, who had a baby and then started, euphemistically, ´working on the midnight shift´ was surely the same Annie who later sang her songs in Tom Paxton´s repertoire ! Over the years I´ve acquired albums by thirty or so other artists who know Annie too.

Chip Taylor´s Last Chance album and that song I Want The Real Thing, in particular, sent me out not only in search of albums, but also led to me writing a book (later published in serial form in a country music magazine) called Their Names Dropped Out In Conversation. This was an exploration of artists who, in their songs, referenced other songs and other artists. The list I ended up with, in the mid-nineties, was by no means exhaustive but was already running into the thousands, and a few years ago I noted that even Chip added further to it with a song called What Would Townes Say About That, which took me all the way back to my friend Townes Van Zandt and the period when my record-collecting was a manly hobby rather than the needy, nerdy geek-ishness that my wife and others say it has become. As I built the collection my then pre-teen son would often tell me that not only was my hobby a boring one, but that the music it collected was rubbish anyway.

He now lives in South Korea where, at forty, he has digitally re-collated virtually all my collection on to his technology and is currently ´researching´ dead musicians like Stan Rogers´ who played the banjo in a certain style. I fear that for my son, in his middle age, geek-ishness beckons.

I, myself, have perhaps only narrowly avoided such geek-ishness, and remain just on this side of the angels rather than on the side of the obsessive music bores I avoid at all costs.

We have recently published on these pages an article by Andrew Moorhouse, a publisher of a fine press poetry collection that includes poets like Armitage and Duffy. Andrew and I once had a minor altercation about Elvis Costello, about whom Andrew gave me an impassioned argument as to why I should listen more closely to Costello´s work,……… I did, and C is now one of the most bursting at the seams letters in the A-Z of artists collected by Norm. Furthermore, I was delighted to publish that article by Andrew, in the hope it might encourage others to follow Sidetracks & Detours to the Attractions Costello might offer.

Still, I have never seen myself as a geek or a nerd, and there was a time in my youth when simply by virtue of the fact that I preferred American bands when most of my peers were liking it with Gerry And The Pacemakers, bending it with Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Titch, and dreaming of a Boom Bang A Bang with Lulu I was buying singles like Pretty Boy Floyd by The Byrds. for six shillings and two pence at the local record store in Tadcaster where I would spend my school summer holidays with my Gran. I would then rush over the bridge over the River Wharf and up the path beside the A64 up Tad Hill and on to the Auster Bank estate to where my older cousin Diane lived, so that I could play it on her record player. She struck a hard bargain, and I always had to listen to half a dozen of her new British singles to hear what I wanted to hear.

That single by The Byrds is evidence that I was aware of even their non-chart music a few years before an incident I´ll never forget. I was by this time attending a college in Walkden. I was a long-haired poet by then, or at least that was my self-perception that didn´t take into account that the rest of the lads were in leather jackets while I was wearing my mum´s cable stitch knitted pullovers. Nor did my self-image include the fact that girls would yawn and walk away when I started talking about my record collection and would actually run away when I started reading them my poetry.

One morning break on ´campus´ I had been the centre of much derision as I waxed lyrical on a subject I knew nothing about, but suddenly the sniggering crowds around me parted, and through the gap I could see Colin Locker, the coolest, but hardest, guy in college striding over. I couldn´t think what I might have done to deserve it, as he and I had hardly ever spoken, but I was sure I was in for a thumping. The gleeful joy emanating from my detractors suggested they, too, thought (and even hoped) I was about to receive retribution for I knew not what. He came and confronted me, virtually nose to nose, and had he not been holding a large brown paper package, I would have been expecting him to thump me. Instead he tore off the wrapping to reveal what seemed to be a pile of maybe a dozen long playing albums, and put them into my arms.

´The Byrds´, he said. ´Listen and learn. Look after them.´

As he walked away I had no idea as to what had just happened, and I certainly had no thoughts that I had just passed through some kind of rite-of.passage in a moment that would change my life forever. Over the rest of my year at college, for some reason I was no longer the butt of every joke. Occasionally someone would even ask me for some musical information they thought I might know or ask me what I thought of particular groups or records.

I´m not sure that, other than the merest occasional nod across the courtyard, Locker and I would ever again acknowledge each other but if he one day wants his records back he´s going to have to fight me for them. Over the years they have seen me follow sidetracks and detours marked P for Parsons, M for McGuinn, D for Dylan and twenty two other destinations besides.

Why Colin Locker did that, I will never know.

Nor will I ever know why I have taken so many roads less travelled but as Steve Goodman had it , ´from the cradle to the crypt is a might short trip, so you´d better get it while you can.´

That was a line of his lyrics in a song about an old-time string band called Martin, Bogan and Armstrong that sent me out in search of their music and I learned that when this nominally three piece ensemble first burst onto the traditional acoustic music it actually had four members.

General retrospectives of them these days is that the group promised more than it ever delivered on record. The legacy and discography is pretty small and many feel it reveals the debut album to have been their ´best´ release. Subsequently, the Flying Fish record label turned the band over to Steve Goodman for genius production, but the results, although enjoyable, hardly have the impact of that first album.

The four members were father and son Howard and Tom Armstrong eventually honing the precision on the band’s name by altering it to Martin, Bogan & the Armstrongs. The senior members of this project were all veterans of the string band scene from the nineteen thirties and forties and that placed them in an elevated position beside young revival bands of the seventies. More importantly, this black string band, although a rarity, was one that seemed comfortable tossing in mountain music, country & western, or even a Hawaiian number. In the latter department, You’ll Never Find Another Kanaka Like Me remains one of this group’s favorite songs among its fans. Much of the repertoire also came from black music traditions, but it was a blend that one only heard from the most versatile artists: blues, swing jazz, and jive that bordered on rock & roll. The fiddle, mandolin, and guitar soloing is excellent throughout. Musically, This Old Gang Of Mine is the band’s most solidly enjoyable album, and adding to the perfection is the packaging, including a good historical essay as well as three delightful cartoons by the elder Armstrong. No information is given about the composers of the titles, however. A few are traditional, but many come from the Tin Pan Alley mill of publishers who were still out watching for every penny that was owed, so the oversight of attribution is surprising. In the nineteen nineties, the label created a CD re-release that combined most of this album with the Goodman-produced material, though Eugene Chadbourn, an excellent archivist in this field argues in his on line essay on Allmusic, that too much good material that might have been included was overlooked.

Nevertheless, a recommendation in those days from Steve Goodman was always one worth following. His song that talked about ´these wise old gents, grey and bent´ that he saw play a score of young pretenders under the table one night is perhaps a reminder that ´live´ was where it was at for this band. Goodman´s lyrics memorably noted that the Martin, Bogan and Armstrong(s) String Band ´was a little bit behind with their payments and a little bit ahead of their time.´

Goodman always had a clever way with a lyric,…I remember that line he,…yes, sorry,… right. I´ll shut up now. Of course I can talk about something else. Have you heard the new Dylan album, by the way?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!