JAZZ OPERA OF EXTRAORDINARY VITALITY by Steve Bewick

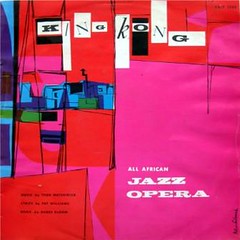

KING KONG A GIANT OF A JAZZ OPERA

by Steve Bewick

One of the most famous movies ever made, involving a big ape being transported to New York from an obscure island, was called King Kong and carried indelible images of the havoc wrought by the fictional creature. However, I recently came across a work that has replaced those images I had in my mind.

The audience settled, ´the orchestra strikes up the opening chords of, Sad Times, Bad Times. The curtain rises on a whole, pale orange sky, low backdrop and shanties, chimneys, electric standards with drooping wires. The township has a bare, forlorn, exhausted look. The houses are shabby and lean on each other, as if precariously holding each other up in their arms.´

So the stage setting is prescribed for the opening of Act 1 of King Kong, a seemingly long-forgotten African Jazz Opera first performed in 1956 and acknowledged as the first all African Jazz Opera.

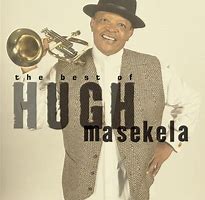

King Kong starred artists who subsequently became international stars, including The Manhattan Brothers with Kippie Moeketsi and Hugh Masekela. The lead female role was performed for some time by Miriam Makeba, who played Joyce, a ´shebeen Queen´ in charge of the Back O´ The Moon drinking den. The cast list extended beyond sixty and performances were accompanied by an orchestra made up of fourteen of the leading jazz players of the time. One of these, reed player Kippie Moeketsi, even drew comparisons with Charlie Parker for his contributions to modern jazz.

The production ran for two years and more in South Africa, drawing some impressive reviews with one newspaper, the Star, aimed at white readership, calling it ´the greatest thrill in twenty years of theatre-going.´ On the back of such reviews the show then transferred for a short, but successful, run in London in 1961.

I came across an old battered Fontana copy, (1962) of this story whilst exploring the book shops of Tel Aviv. It is a story by Harry Bloom, lyrics by Pat Williams with music (and assorted patois) by Todd Matshikiza and was produced for the stage by Leon Gluckman.

Harry Bloom, the author, was from a Jewish South African family. He lived in London during the war and changed his name to avoid anti-semitism and then returned to South Africa to employ his writing skills to challenge the racial attitudes prevalent there at the time.

Lyricist Pat Williams was a actually journalist of wide international experience. Having joined The Cape Times at the age of eighteen she subsequently wrote specialised articles on a wide range of subjects for The Sunday Times and served for some while as the newspaper´s film and theatre critic.

Todd Matshikiza was a ´musician of exceptional talents´ was one of a family of ten, all of whom were either singers or musicians. In 1956 he wrote Uxola, a choral work for 200 voices and orchestra that was performed later that year at the Johannesberg Festival.

The cover notes of the little book I picked up promised …… “a violent yet moving story of a coloured boxer in a South African shanty town, of his girl Joyce who deserts him when he begins to lose, and of his enemy Lucky, the gangster.”

My research has since revealed glowing reviews at the time from no less than The Sunday Times, stating, “Extraordinary vitality, colour and geity….it ends on a note so sad, so eloquent that we are lost in pity and admiration”

Time magazine said of King Kong that it, “Triumphs….by its bursting, smoking, glowing life.”

I was not to be disappointed. This was not an ordinary novel I had discovered, but the script, stage notes and lyrics of one of the most compelling operas to have been created in South Africa, yet barely heard of today, We know West Side Story, of course and Street Scenes, yes. We consider Carman even, but not King Kong.

The background to the story was life in South Africa for the blacks and coloured population under the apartheid regime. Gluckman no doubt wanted to see improvement in South Africa. King Kong provided the perfect medium for these ambitions. The world was to be given the opportunity to see life in the Townships as it really was.

The story is set in 1957 soon after the death of one Ezekiel Dhlamini. Ezekiel called himself King Kong, but not out of admiration of the jungle monster of Edgar Wallace. He simply liked the name. He was also known as `Marshal`, `Smasher` and `Big`. All ego building names for a hero of the boxing ring.. In the world of non-white boxing he became a famous champion. The crowds loved him. They flocked to his fights. He would often entertain his fans with a post-match pavement exhibition of how he had smashed his opponent.

Yet his real life persona was one of a bully, a braggart and a brawler who would often thrash a man on the street for giving the wrong look, or smiling at the wrong moment. He constantly demanded praise and attention. His popularity was based on a desire for glamour, excitement and adventure within South Africa that many craved as a way out of poverty.

However, Ezekiel was denied access to the white boxing community and its fame, women and money. He lapsed in his training. He became over confident of his powers in the ring. On one occasion, whilst losing a fight to a middle weight opponent, he was knocked out of the ring. King Kong became a joke.

For a while no one heard of him until he appeared in court for killing a gang member in a brawl, although he was acquitted on the grounds of self-defence. It was not long before he was up in court again.

This time he was charged with the murder of his girlfriend in a fit of jealousy when she arrived at a dance hall with rival gangsters. He urged the judge to find him guilty and to sentence him to death. He was gripped with remorse. The judge instead sentenced him to 15 years hard labour, stating that his girlfriend had provoked him in his act.

His life’s ordeal was to come to an end soon after the start of his imprisonment when his remorse drove him to suicide by drowning himself in a nearby dam where he was working. His death was to reinstate him as a popular hero. He died at the age of just thirty two.

The story works at several levels and echoes in these modern times, a foray into historical nonfiction, life under apartheid, poverty and alienation. Ezekiel personifies sexism in his actions and the actions of the establishment in not wishing to make an example of his misdemeanours and treatment of women. The book looks at alienation from society and tells of how the boxer sought to address this through by acquiring stardom, fame and money in a mirror image of Joe Louis in America. Dis-affected and dis-enfranchised youth today might seek a similar way out through football to fortune and fame. Hip hop and gangsterism seem today to have become other favourite routes of escape.

That there has been no contemporary revival of this play is not least, perhaps, because South Africa, post-Apartheid, would prefer the worlds image of the nation state as being modern, corruption free and offering new opportunities to its youth. The story is out-dated in its ´yesterday context and would need a modern backdrop. Its pace remains racy and relevant to a modern story´however, pulling in readers at each turn of events. The soul of Ezekiel goes through many phases as the hero and anti-hero rising once more as a spirit of hope on his death.

In some ways the story is a victim of time. Yet Ezekiel is the character many youth might aspire to as he found a way out of a poverty that still exists for them today. Escape routes today perhaps follow sidetracks and detours through different genres.

Of course, theatre itself might not only illustrate the plight of the dis-enfranchised through the stories it tells, but might also offer an escape route from such circumstances through the work the industry provides. The country´s theatre emerged from the rich and ancient traditions of indigenous South Africans and their love of folk tales told around the ´camp-fires´ for which the audiences consisted of young and old together. Modern history traces a development of an eclectic performance culture centred around the vibrant Sophiatown area of Johannesberg. This drew on cultural traditions from America and Africa and England, that included comedy, song and dance and jazz.

So, this rare gem that I found in twenty first century Israel not only reminded me of a cultural history from another continent, but of a jazz era that produced some important players.

Zenzile Miriam Makeba, (left) who played Joyce, was a South African singer, songwriter and actress, who went on to work as United Nations goodwill ambassador, and civil rights activist. Associated with musical genres including Afropop, jazz, and world music, she was an advocate against apartheid and white-minority government in South Africa and came to be known as Mama Africa.

Hugh Ramapolo Masekela, who also took part in stage performances of King Kong, was a South African trumpeter, flugelhorn player, cornetist, singer and composer who has been described as ´the father of South African jazz´. Known for his jazz compositions and for writing well-known anti-apartheid songs such as Soweto Blues and Bring Him Back Home, Masekela also had a number-one US pop hit in 1968 with his version of Grazing In The Grass.

I was reminded of all this by a little book I bought in a bookstore in Tel Aviv that invited me to follow my art and led me down all sorts of intriguing sidetracks and detours.

Steve Bewick Jazz Broadcaster

Facebook/stevebewick

- Some background information supplied by Norman Warwick

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!