GO YOUR OWN WAY

GO YOUR OWN WAY

by Norman Warwick

Some musicians I have interviewed over the years have carried a very different persona to what I had perhaps anticipated. Guy Clark, partly because he was such a big man with a huge presence could, for one so softly spoken, be quite intimidating. I interviewed my great hero John Stewart a number of times. We often reached an impasse because I considered him to represent Americana through and through, having come round the folk circuit out on to the country roads, when in fact he saw himself, I think, as a rock musician. He did, after all, record hits with Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham (and with the latter he even exchanged ´tribute´ songs) and I learned something about that relationship in a couple of talks. From something I´ve recently read in Paste on-line magazine I reckon that if John Stewart was the most difficult challenge I faced as an interviewer, it was perhaps only because I never had the chance to interview Lindsey Buckingham. So come follow you art down sidetracks & detours to places where people ´tear down the sky´.

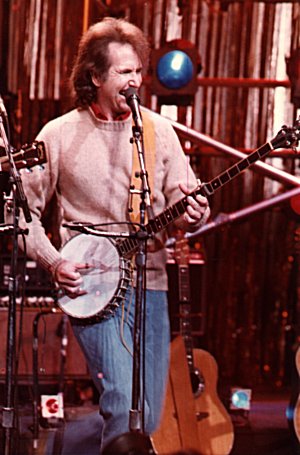

The apprentice learned from his master and created guitar magic. Or to put it more simply, Lindsey Buckingham taught himself to play guitar was listening, enthralled, to John Stewart´s banjo picking with The Kingston Trio (left). Years later the two men recorded together and Buckingham lent some brio to Stewart´s sound, although it has to be said that Stewart himself was a fine guitarist, and put together beautiful overlaid acoustic and electric runs that Buckingham, even on his brand new album, still frequently echoes. Buckingham and Stevie Nicks, who had been discovered as a musical duo in a recording studio and invited to join Fleetwood Mac helped Stewart deliver his first hit album and a couple of hot singles like Gold.

It was on one of his several home-made albums that we learned from John Stewart of advice he gave Buckingham as Rumours ran around suggesting the less-than-love lives of the Fleetwood Mac wearers and the naked ambition of each of the individuals was threatening to split the band.

In a song to ´Liddy Buck´, John Stewart wrote ´you´ve flow too high, you´ve run too far, you´re gonna tear down the sky for a star´.

The track Johnny Stew, which Buckingham offered in return on his debut solo album was certainly a dish better served cold. Bouncy and seemingly affectionate in nature it nevertheless somehow suggested John to be an angry, impatient man,….which was kind of what John had said, just as affectionately, about him !

Sidetracks And Detours recently posted an article that borrowed Stewart´s title of Tear Down The Sky, Liddy Buck, and are delighted to so quickly follow that up with a review of Buckingham´s new album, released just a few days later.

It can be tough to sympathize with Lindsey Buckingham. The ex-Fleetwood Mac guitarist hasn’t released much since his solid 2017 collaboration with Mac keyboardist Christine McVie, simply titled Lindsey Buckingham/Christine McVie, but he’s kept busy in the meantime. Along with delivering a soaring guitar solo on The Killers’ “Caution,” Buckingham has had a heart attack, damaged his vocal cords, gotten divorced and was fired from Fleetwood Mac, all since 2018. Now that he’s gearing up to release his solo first album in 10 years, he’s picked a public fight with Fleetwood Mac vocalist Stevie Nicks, former life partner and band-mate, perceived as having kicked him out of the band for kicking him out of the band. Being in a relationship and recording duo that recorded an album together (right), then together joined a band that they helped turn into the biggest in the world, documenting their disharmony on the band´s biggest album seems symptomatic of the drama and stubbornness that he’s always engaged with. The last few years have painted a picture of Buckingham as someone who doesn’t have much in the way of good luck or good instincts, but may still have a couple of good songs to share. With the eponymous Lindsey Buckingham, he keeps on keeping on, making an enjoyable album that can occasionally compete with his best.

On Buckingham’s previous solo venues, from his off-putting debut Law And Order to 1992’s underrated Out Of The Cradle, he’s stuck with the textures and sounds he’s most comfortable with. From programmed and often chunky drum-work to sterling, clean electric guitars, all of which is often laced with the goofiest synthesizers you could dream of, Buckingham (left) has created a distinct style for his solo material—one that often implies he needs his Fleetwood Mac bandmates to bounce ideas off. Even on Lindsey Buckingham, he’s still working within the confines he first laid out 40 years ago, but this collection shines brighter than most of his previous solo work. Buckingham’s vocals sound clearer and the guitars are now much kinder on the ears, but most importantly, he sounds far more invested in the relationship dynamics that he lays out on album highlight Santa Rosa than he ever did on Law and Order’s eccentric and exhausting Bwana or That’s How We Do It in L.A. ´

Buckingham’s investment in crafting comfortable-sounding, sometimes emotionally resonant songs here makes his head-scratching production habits more bearable. Take the album’s opener, “Scream,” which uses propulsive power chords to keep things moving, even if it has percussion that sounds like it’s being played with silverware. The song’s lyrics are a bit nonsensical, filled with Buckinghamisms like “Over and over, red, red rover,” or “Down in the valley, hearts dilly-dally,” but he self-corrects with a decently affecting chorus. When he reaches the hook’s final line, Buckingham’s voice jumps up into his upper register. “Nighttime’s the time I love so much / Lost in the language of your touch,” he sings, the most passionate he’s sounded in years.

Throughout the press cycle for Lindsey Buckingham, he’s made clear that this record was made in his home studio without anyone else playing on it. At times, this adds to the album’s tightness and limited scale, but it occasionally begs for more inventive playing. Sure, the nylon acoustic guitars of Blue Light and giant electric solos are excellent. With Buckingham, that’s just par for the course, but often the drumming is in need of more personality and the bass work rarely adds much to these songs. The average , Blind Love, acts as a perfect example, as it’s a song that has plenty of shining, layered harmonies and touches of auxiliary percussion, but the plodding drumwork feels like a pre.set GarageBand loop. It’s easy to feel the same way about the Pozo-Seco Singers cover, Time, which swaps the original’s doo-wop sentimentality for a far more watery arrangement.

Thankfully, there’s a single song on this album where the percussion absolutely makes the song. With Swan Song, Buckingham has programmed an relentlessly pushing, drum- and bass-tinged beat that only adds to the song’s paranoid, strained atmosphere. Using healthy doses of reverb, processed vocals, and harmonies, he turns the chorus of “Swan Song” into a monument for making the most tense Lindsey Buckingham song possible. “Is it right to keep me waiting? / Is it right to make me hold out so long?” he asks, right before we get a superb guitar solo that builds and modulates as if he’s searching for a place to land it.

Swan Song very well might be the best song on Lindsey Buckingham, but it’s got some healthy competition from On the Right Side. With a bouncy indie-pop groove underneath him, Buckingham seems to display a hint of self-awareness for the first time: “I’m out of pity, I’m out of time, another city, another crime,” he sings, like he’s lamenting the bridges he’s burnt and mistakes he’s made.

The chorus is classic Fleetwood Mac (right) , stacked to the heavens with vocals on vocals, but the entire thing feels more melancholic than what Buckingham is used to making. After a final hook, “On the Right Side” ends with another incredible guitar solo that fades out slowly with the rest of the song. It’s a fitting image to pair with this album, Buckingham now a virtuoso standing alone with his guitar playing, having alienated all of his band-mates. All that’s left for him is his instrument.

There are those who feel that the best single of the summer of 21 was On the Wrong Side, sounding like a long-lost gem from Fleetwood Mac’s heyday in the ’70s and ’80s. It has all the hallmarks of that period: confessions of ill ease while “living life in overload,” the lyrics counteracted by sumptuous three-part, male-and-female harmonies, and melodic guitar motifs, all over a no-nonsense propulsion at the bottom.

But not only does the song come from this year’s Lindsey Buckingham, the musician’s first solo album in 10 years, but he also recorded every vocal and instrument himself. He even did the female-vocal parts by raising the pitch of his voice with help from a variable speed oscillator. It’s proof positive that the chief architect of Fleetwood Mac’s four classic studio albums—Fleetwood Mac, Rumours, Tusk and Tango in the Night—can still summon that sound at will. He even admits that this new tune is the musical sibling of his earlier signature song, Go Your Own Way.

But Buckingham doesn’t always want to work in that vein. “I wanted to make a pop album,” he declares in the album’s press materials, “but I also wanted to make stops along the way with songs that resemble art more than pop.” And indeed, most of the album is devoted to more stripped-down arrangements with quirky blends of acoustic and electric instruments over simple drum loops and layers of breathy vocals. The melodies are always hooky and the harmonies always sumptuous, but the minimalism makes them sound more like chamber-rock than the arena-rock of his old multi-platinum band. And he’s fine with that.

“When I’m in the band mode,” Buckingham explains over the phone from his Los Angeles home, “recording an album is more like moviemaking. You bring in your song like it’s a script, and you have to verbalize to the actors and crew what you want done with it. And it becomes a cocktail of everyone’s contributions. The budgets are bigger, and everything is more political. When I’m in the solo mode, it’s more like painting. The song doesn’t have to be as fleshed out when I go into the studio. I can be alone and slop paint on the canvas. I can let the paint speak to me, as well as me speaking to it. The song can come to life while you’re working on it.

“I tried to introduce some of that process into Tusk,” he recalls. “It was a line I drew in the sand to protect us from commercial considerations. But when that album didn’t sell as well as the previous one, it became difficult to maintain that experimental approach. That’s why I started doing my solo projects, so I would have an outlet for that side of my music. It’s a trade-off: You gain some freedom, but you lose a lot of the audience.” At this point, he switches metaphors. “It’s like Jim Jarmusch, who makes movies with the freedom of experimentation, but he knows that they will never have an audience like Steven Spielberg’s films.”

“I Don’t Mind,” the first single off Buckingham’s solo album, resembles a Jarmuschian indie film more than a Spielbergian/Fleetwood Mac blockbuster. The opening blend of hushed voices and prodding guitar relies more on mesmerizing atmosphere than conventional exposition. The lyrics are a succession of tantalizing fragments, rather than a linear narrative or monologue. This small-scale song works because Buckingham doesn’t rely on a single hook, but creates two hooks for the lead vocal, two different hooks for the backing vocals and two more for the lead guitar, all locking together like puzzle pieces.

Buckingham insists he doesn’t want to limit himself to only making small, experimental records or only making big, commercial records. He likes doing both. If he had had his way, he would still be in Fleetwood Mac, joining their recordings and tours, and working on his solo projects in between. But when he had the album Lindsey Buckingham almost ready for release in 2018, he asked his bandmates to delay their tour for three months so he could do a solo tour behind the project. Instead, they fired him from the band.

Stevie Nicks, (left) who was Buckingham’s girlfriend from 1967 to 1976 and his band.mate from 1967 to 2018, claims she didn’t fire him, but rather fired herself, forcing the other band members—Mick Fleetwood, John McVie and Christine McVie—to choose between the feuding exes. Nicks possesses the greater commercial sway, and the band members went with her—which makes sense if you’re mounting a nostalgia tour of your biggest hits. Buckingham told the L.A. Times that Christine McVie later emailed him to say, “I’m really sorry that I didn’t stand up for you, but I just bought a house.”

When she was less worried about her mortgage and more worried about making a new album, she reached out to Buckingham to massage her song-writing into Spielbergian pop singles as he had so often in the past. Those sessions were released in 2017 as the delightful album Lindsey Buckingham/Christine McVie, (right) featuring five lead vocals by each of them. but there had been hopes that these songs might have become a new Fleetwood Mac album.

“Before Christine rejoined the band in 2014,” Buckingham says, “Mick, John and I had already gone into the studio in 2013 with producer Mitchell Froom to cut some songs of mine. We finished them except for leaving room for Stevie’s voice. But Stevie wasn’t interested; I think she didn’t have any new material and felt bad about it. So that album didn’t happen, but Stevie did pull out an old song, so we put out an EP with three of my songs and that one of Stevie’s, and we went out on tour as a four-piece.

“When Christine came back, we had these songs left over from the Mitchell Froom sessions, plus some new songs I’d written. Christine was sending me songs she had written, and I was working on them in my studio. I sent her some tracks with melodies that I was working on, and she put words to them. We were hoping that when Stevie heard what we were doing, it would draw her in, but she wasn’t interested. So we released it as a duo album.”

It was a period of renewed creativity for Buckingham, who began writing the songs for this year’s solo album even as he was working on the duo album. When he and McVie hit the road behind the duo release (backed by Buckingham’s band), the tour was “an eye-opener for Christine and Marty Hom,” the longtime Fleetwood Mac road manager.

“It was the first time they’d seen me without the politics and circus surrounding Fleetwood Mac,” Buckingham recalls. “They saw another part of me and how I approach music when I’m away from the band. We played much smaller places and put on a show that had a more artistic bent to it. Christine really enjoyed it.

“Christine’s a great songwriter with a great pop voice. She’s the middle ground between Stevie and me, because she’s grounded in her musicianship while Stevie’s more ethereal. If you take Christine out of the equation, you get a stylistic polarity between Stevie and me. When she’s there, she provides a middle that holds the band together.”

Fleetwood Mac began as a British blues band in 1967 when three-fourths of John Mayall & The Bluesbreakers—drummer Mick Fleetwood, bassist John “Mac” McVie and guitarist Peter Green, (left —went off on their own, with Jeremy Spencer as second guitarist. By 1970, however, Green’s mental instability overtook his instrumental brilliance, and the band was forced to carry on with guitarists Spencer and Danny Kirwan and keyboardist Christine McVie, who had just married the band’s bassist. Spencer walked away from the band mid-tour in 1971 to join a religious group, and Bob Welch took his place.

Without Green, however, the band was not thriving commercially or artistically. There was more turnover, and the band completely fell apart during a 1973 tour. But the drummer would not let the band die.

“It was a band that was led spiritually by Mick Fleetwood,” Buckingham observes, “who was not a writer but who was a vibe master. He was the one that kept the band together after Peter and Danny left. Mick has a great set of instincts. He believes in things coming together because he believes in himself. He believed not only that success was out there waiting for the band, but also that he needed to be seen and heard. He was also very open to new possibilities.”

Fleetwood was checking out the Sound City Studio in L.A. in 1974, when engineer Keith Olsen played him a track from the little-known album Buckingham Nicks, recorded at the studio, where Buckingham happened to be working on new demos. “I heard ‘Frozen Love’ playing and I walk into the control room,” Buckingham recalls. “I see this tall guy bopping to my guitar solo, and I said hello. On the basis of that conversation, he offered me a job. I said, ‘Only if you also take my girlfriend.’”

This was more than just another turnover in personnel; this was a total revamping of the band’s sound. The last vestiges of the group’s blues origins were swept away—immediately in the studio and gradually onstage—and replaced by California pop harmonies. Buckingham and Nicks were both Californians, and Christine McVie’s melodic instincts flourished with the switch. The rhythm section was as powerful and efficient as ever.

But this was not the unalloyed optimism of Dick Dale or Jan & Dean; this was the more complicated California music of the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson, whose hopes for love and popularity were always haunted by fears of rebuff. The hopefulness was usually in the foreground, but the wariness was always in the background, creating an irresistible musical tension. This tug-of-war dynamic would mark Buckingham’s songwriting, as well, for his entire career. He even co-wrote a song with Wilson, “He Couldn’t Get His Poor Old Body to Move,” which ended up as the B-side on Wilson’s 1988 single, “Love and Mercy.”

“Perhaps the greatest A and B sides of the same single in history are the Beach Boys’ ‘I Get Around’ and ‘Don’t Worry Baby,’” Buckingham argues. “One is about the joy of riding around town, and the other is the worry of what could go wrong while riding around town. And in both cases, the music is transcendent. Brian’s reaching for that happy ending, but that sadness that is always there, probably going back to his upbringing.”

You can hear that on Lindsey Buckingham. On “I Don’t Mind,” he sings, “Where there’s joy, there must be sorrow, never far apart,” and that push-and-pull is reflected in the contrast between the uneasy verses and the carefree chorus. “Still crying about joy, still laughing about pain,” he sings to the bouncy, happy-go-lucky melody of “Blue Light.” The most gorgeous song on the album, “Santa Rosa,” is also the most heart-breaking. Buckingham sings to a woman who is leaving the home they built together in L.A. to move to northern California, and his voice fluctuates between despair and stoic acceptance.

“I never took up surfing,” he confesses, “but I could definitely relate to the whole vision created by Brian Wilson´s songs (right) . It wasn’t about the subject matter; it was about Brian’s musical genius. Those songs were part of our community; it was where I lived. Of course, romantic angst is timeless and universal.”

Back in 1974, as the new line-up started work on the album that would become Fleetwood Mac, Buckingham realized he would have to take on a different role than he was used to. “I had to give up some things in my own performance, but that was OK,” he says. “I couldn’t play as much guitar as I was used to playing, I had to pare back to make room for John’s melodic and sometimes busy bass playing, and Christine’s keyboards.

“At the same time, it became apparent to me that one of my jobs was to be producer/musical director. You had these three different writers who were each very different in their styles. You had Christine and Stevie, whose songs needed some augmentation from me as a producer to reach their potential. John McVie was so versed in the blues that he was a bit ambivalent about this California thing. But somehow all these pieces jelled into one thing.”

There are those who feel that the best single of the summer of 2021 was On the Wrong Side, sounding like a long-lost gem from Fleetwood Mac’s heyday in the ’70s and ’80s. It has all the hallmarks of that period: confessions of ill ease while “living life in overload,” the lyrics counteracted by sumptuous three-part, male-and-female harmonies, and melodic guitar motifs, all over a no-nonsense propulsion at the bottom.

But not only does the song come from this year’s Lindsey Buckingham, the musician’s first solo album in 10 years, but he also recorded every vocal and instrument himself. He even did the female-vocal parts by raising the pitch of his voice with help from a variable speed oscillator. It’s proof positive that the chief architect of Fleetwood Mac’s four classic studio albums—Fleetwood Mac, Rumours, Tusk and Tango in the Night—can still summon that sound at will. He even admits that this new tune is the musical sibling of his earlier signature song, “Go Your Own Way.”

“It was the first time they’d seen me without the politics and circus surrounding Fleetwood Mac,” Buckingham recalls. “They saw another part of me and how I approach music when I’m away from the band. We played much smaller places and put on a show that had a more artistic bent to it. Christine really enjoyed it.

“Christine’s a great songwriter with a great pop voice. She’s the middle ground between Stevie and me, because she’s grounded in her musicianship while Stevie’s more ethereal. If you take Christine out of the equation, you get a stylistic polarity between Stevie and me. When she’s there, she provides a middle that holds the band together.”

Fleetwood Mac began as a British blues band in 1967 when three-fourths of John Mayall & The Bluesbreakers—drummer Mick Fleetwood, bassist John “Mac” McVie and guitarist Peter Green—went off on their own, with Jeremy Spencer as second guitarist. By 1970, however, Green’s mental instability overtook his instrumental brilliance, and the band was forced to carry on with guitarists Spencer and Danny Kirwan and keyboardist Christine McVie, who had just married the band’s bassist. Spencer walked away from the band mid-tour in 1971 to join a religious group, and Bob Welch took his place.

Without Green, however, the band was not thriving commercially or artistically. There was more turnover, and the band completely fell apart during a 1973 tour. But the drummer would not let the band die.

“It was a band that was led spiritually by Mick Fleetwood,” Buckingham observes, “who was not a writer but who was a vibe master. He was the one that kept the band together after Peter and Danny left. Mick has a great set of instincts. He believes in things coming together because he believes in himself. He believed not only that success was out there waiting for the band, but also that he needed to be seen and heard. He was also very open to new possibilities.”

Fleetwood was checking out the Sound City Studio in L.A. in 1974, when engineer Keith Olsen played him a track from the little-known album Buckingham Nicks, recorded at the studio, where Buckingham happened to be working on new demos. “I heard ‘Frozen Love’ playing and I walk into the control room,” Buckingham recalls. “I see this tall guy bopping to my guitar solo, and I said hello. On the basis of that conversation, he offered me a job. I said, ‘Only if you also take my girlfriend.’”

This was more than just another turnover in personnel; this was a total revamping of the band’s sound. The last vestiges of the group’s blues origins were swept away—immediately in the studio and gradually onstage—and replaced by California pop harmonies. Buckingham and Nicks were both Californians, and Christine McVie’s melodic instincts flourished with the switch. The rhythm section was as powerful and efficient as ever.

But this was not the unalloyed optimism of Dick Dale or Jan & Dean; this was the more complicated California music of the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson, whose hopes for love and popularity were always haunted by fears of rebuff. The hopefulness was usually in the foreground, but the wariness was always in the background, creating an irresistible musical tension. This tug-of-war dynamic would mark Buckingham’s songwriting, as well, for his entire career. He even co-wrote a song with Wilson, “He Couldn’t Get His Poor Old Body to Move,” which ended up as the B-side on Wilson’s 1988 single, “Love and Mercy.”

“Perhaps the greatest A and B sides of the same single in history are the Beach Boys’ ‘I Get Around’ and ‘Don’t Worry Baby,’” Buckingham argues. “One is about the joy of riding around town, and the other is the worry of what could go wrong while riding around town. And in both cases, the music is transcendent. Brian’s reaching for that happy ending, but that sadness that is always there, probably going back to his upbringing.”

The pieces fell into one thing on Buckingham´s first solo album since ´being sacked´ from Fleetwood Mac, and it so represents some of his finest work that there are rumours whispering in the grapevine that he might soon be invited back.

The prime source for this article was a piece written by Ethan Gordon, for Paste on-line magazine

Ethan Gordon is a writer living in Pittsburgh. His work can be found at No Ripcord, Vice, Mic and others.

In our occasional re-postings Sidetracks And Detours are confident that we are not only sharing with our readers excellent articles written by experts but are also pointing to informed and informative sites readers will re-visit time and again. Of course, we feel sure our readers will also return to our daily not-for-profit blog knowing that we seek to provide core original material whilst sometimes spotlighting the best pieces from elsewhere, as we engage with genres and practitioners along all the sidetracks & detours we take.

This article was collated by Norman Warwick, a weekly columnist with Lanzarote Information and owner and editor of this daily blog at Sidetracks And Detours.

Norman has also been a long serving broadcaster, co-presenting the weekly all across the arts programme on Crescent Community Radio for many years with Steve, and his own show on Sherwood Community Radio. He has been a regular guest on BBC Radio Manchester, BBC Radio Lancashire, BBC Radio Merseyside and BBC Radio 4.

As a published author and poet he was a founder member of Lendanear Music, with Colin Lever and Just Poets with Pam McKee, Touchstones Creative Writing Group (where he was creative writing facilitator for a number of years) with Val Chadwick and all across the arts with Robin Parker.

From Monday to Friday, you will find a daily post here at Sidetracks And Detours and, should you be looking for good reading, over the weekend you can visit our massive but easy to navigate archives of over 500 articles.

The purpose of this daily not-for-profit blog is to deliver news, previews, interviews and reviews from all across the arts to die-hard fans and non- traditional audiences around the world. We are therefore always delighted to receive your own articles here at Sidetracks And Detours. So if you have a favourite artist, event, or venue that you would like to tell us more about just drop a Word document attachment to me at normanwarwick55@gmail.com with a couple of appropriate photographs in a zip folder if you wish. Beiung a not-for-profit organisation we unfortunately cannot pay you but we will always fully attribute any pieces we publish. You therefore might also. like to include a brief autobiography and photograph of yourself in your submission. We look forward to hearing from you.

Sidetracks And Detours is seeking to join the synergy of organisations that support the arts of whatever genre. We are therefore grateful to all those share information to reach as wide and diverse an audience as possible.

correspondents Michael Higgins

Steve Bewick

Gary Heywood Everett

Steve Cooke

Susana Fondon

Graham Marshall

Peter Pearson

Hot Biscuits Jazz Radio www.fc-radio.co.uk

AllMusic https://www.allmusic.com

feedspot https://www.feedspot.com/?_src=folder

Jazz In Reading https://www.jazzinreading.com

Jazziz https://www.jazziz.com

Ribble Valley Jazz & Blues https://rvjazzandblues.co.uk

Rob Adams Music That´s Going Places

Lanzarote Information https://lanzaroteinformation.co.uk

all across the arts www.allacrossthearts.co.uk

Rochdale Music Society rochdalemusicsociety.org

Lendanear www.lendanearmusic

Agenda Cultura Lanzarote

Larry Yaskiel – writer

The Lanzarote Art Gallery https://lanzaroteartgallery.com

Goodreads https://www.goodreads.

groundup music HOME | GroundUP Music

Maverick https://maverick-country.com

Joni Mitchell newsletter

passenger newsletter

paste mail ins

sheku kanneh mason newsletter

songfacts en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SongFacts

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!