GUY CLARK: craftsman of character

GUY CLARK: craftsman od character

by Norman Warwick

Guy Clark was born in Monahans, Texas in November 1941 and became a highly acclaimed singer writer with a special talent for narrative songs that capture an America of an integrity of character that today is rapidly fading. No great vocalist, Guy nevertheless communicated with his audiences, and I count myself fortunate to have seen him perform in the UK several times in the last few years.

He died, at the age of 74, described by Rolling Stone in their eulogy as ´the Texas troubadour who blended high wit with pure poetry and turned it into timeless, vibrantly visual songs like Desperados Waiting for a Train and L.A Freeway.´

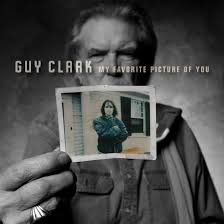

In the final few years of his life, Clark, (shown in our top picture with wife Sussana and Townes and a guitar) had been battling failing health, but still remained prolific: his most recent LP, 2013’s My Favorite Picture of You (right), won a Grammy Award for Best Folk Album. In it, he told of a particular photograph of his beloved wife, Susanna, who passed away the year prior from lung cancer:

´my favorite picture of you is the one where your wings are showing,” he sang in his warm, ragged cool tone. As always, he could see what both was and wasn’t there with the clearest of vision.

Clark recalled a youth where an emphasis was placed on inspiration and intellect — his father, who fought in World War II and went on to obtain a law degree, would lead the family through dinnertime poetry readings, making sure his son learned to use what would become his most vital gift: his imagination. There were no television sets at home — Clark turned to literature instead and eventually sports, playing on multiple teams in high school while he learned the ropes of the guitar, an instrument which he would eventually not only master playing but als even learn to build in the basement of his home in Nashville. He studied not just traditional strumming but was enchanted by Mexican folk and flamenco, sounds that could still be heard on his most recent songs, like El Coyote.

In 1963, Clark joined the Peace Corps, and, after realizing that he’d rather play music and delve much deeper into the folk tradition than attending college could ever offer him, he moved to Houston. He made a living repairing guitars and playing gigs around town at venues like Oak Water, Liberty Hall, the Jester Lounge and Sand Mountain — it was there he met fellow songwriters like Townes Van Zandt, who went on to carve an equally legendary career until his death in in 1997. Guy and Townes became friends, colleagues and admirers of each other’s work throughout their lifetime together, often known as the two most ardent poets of the Texas folk-country tradition: Lyle Lovett once described Clark as the prose-master to Van Zandt’s poet. In Houston, Clark also met Susanna Talley, whom he would later marry.

Later, Clark moved to Los Angeles for a brief stint: one immortalized in the song L.A Freeway, (a song that first introduced me to Guy´s work when I heard Pete Benbow play it in a folk club I ran in Heywood, Lancashire in the nineteen seventies,) He continued to build instruments and write songs, flirting in the publishing and professional song-writing world: but Los Angeles wasn’t for him, as anyone listening to that very song could detect in its chorus line as he mused ´if I could just get off of that L.A freeway without getting killed or caught,´. By then his friends from Houston — an expanding circle including Van Zandt, Jerry Jeff Walker, Steve Earle, Billy Joe Shaver and Rodney Crowell — were all gravitating toward Nashville.

By the time I was working as a freelance music journalist in the eighties and nineties I was interviewing artists like these whenever they toured the UK, and I was never in doubt of the mutual respect between them all. It was noticeable though how it was the friendship of Clark and van Zandt and their bodies of work that had acquired almost legendary status among songwriters of the Americana genre.

He moved there in the Seventies, where he would continue to sculpt the songs that would become his first album, Old No. 1. Featuring him on the cover in his classic denim-on-denim in a painting by his wife, it contained songs — like Desperados Waiting For A Train, Rita Ballou and That Old Time Feeling — that would go on to define his catalogue. It was recorded at RCA Studios on Music Row.

Clark, while establishing an artistic hub at the centre of the pulsing Seventies song-writing scene at his East Nashville home with Susanna (a life depicted in detail in the documentary film Heartworn Highways), went on to be extremely prolific through the years. While his first recordings were for RCA, he had deals with Warner, Sugar Hill and lastly Dualtone, not only writing for himself (and having his songs covered by everyone from Willie Nelson to Vince Gill), but also collaborating with his many friends and admirers.

Later in life, he would embrace co-writes more frequently, enjoying collaborations with younger artists like Shawn Camp. Many of Clark’s songs went to Number One, though not when sung by Clark himself: the breakthrough was when Ricky Skaggs took Heartbroke to the top of the charts. Many other covers, including a legendary take on Desperados Waiting On A Train by The Highwaymen, helped him become one of the most admired songwriters in a world where commercial was increasingly being favoured over craft. Nevertheless Clark, whether shaping a lyric or the body of a guitar, was the ultimate craftsman. However, he never quite climbed the charts himself — a modest showing for 1983’s Homegrown Tomatoes was his best demonstration of commercial success.

Clark was nominated for numerous Grammy awards, though he would joke that he always lost to Bob Dylan. His luck changed when My Favorite Picture Of You, which turned out to be his last album, took home the award in 2014. By then, a past struggle with cancer had ravaged his system as had the toll of hard living — equally so the death of his wife in 2012. His touring life, though once strong and vital, had slowed down, and he had taken to walking with a cane, but he still frequently invited friends and collaborators down into his basement studio to write, smoke cigarettes and play guitar, even though he was no longer able to stand long enough to craft the instruments himself. On the wall, hung the photo of Susana that inspired those last songs: her arms crossed, her eyes blazing. Though no one else could, Clark could see those wings — and now, through his immeasurable contributions through the art of the song — his are clearly spread, too.

In his infancy Guy was brought up by his grandmother, (his mother being out at work and his father away at war) who ran a small, decrepit hotel, peopled with characters with life stories that later would be vividly re-told in song, by a man with an eye for minute detail. During those childhood times Guy would devour and digest a varied musical diet of blues, country and western, cajun and even Mexican mariachi Indeed, Mexican music was what he first learned to play on guitar before moving on to what he described as Traditional Folk. After the war, the family move to Rockport, a tiny fishing village near Corpus Christie, and living on the coast would also inspire his later song writing in evocative compositions such as South East Of Texas.

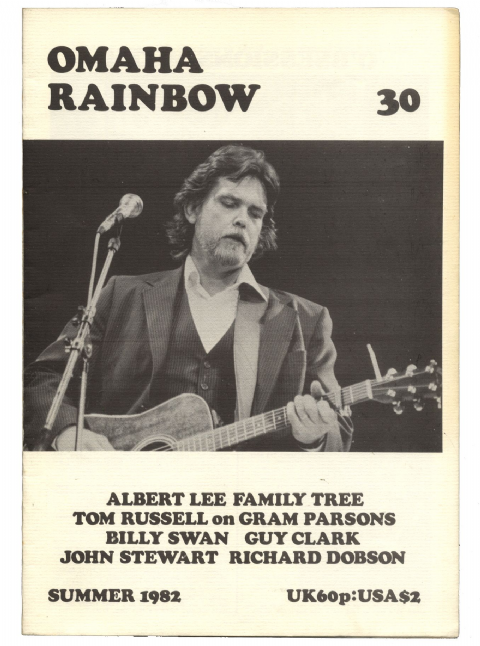

When talking to Peter O´Brien (editor of Omaha Rainbow, the best singer-writer magazine I´ve ever seen) in the Spring of 1982, Guy described the village fishermen as ´an international breed, and all the languages are spoken´ and said that growing up in Rockport had given him a line in that song about living on the edge of the waters of the world.In the course of an excellent interview Guy recalled days when he would tear along ´oyster shell roads in the car of my youth.´ a ´49 Packard.

But the time came to move on, and after graduation from high school, Guy moved to Houston where he worked as an art director at a TV Station. Whilst in Houston he shared a flat with Gary White, writer of Long, Long Time which was later recorded by Linda Rondstadt, and began performing on the local folk club circuit. This brought him into contact with other aspiring acts such as Mickey Newbury (later to write San Francisco Mable Joy and collate an American Trilogy, Jerry Jeff Walker who would write Mr. Bojangles, and Townes Van Zandt who became regarded as the songwriters´ songwriter (all of whom have appeared frequently down our Sidetracks & Detours)) and, after ten years of playing guitar, Guy fell so much under the influence of these singer writers that he, too, began writing his own material.

During this period Guy met and married Susanna, with Townes serving as his best man.

To further Guy´s musical career the newlyweds moved to Los Angeles where the songwriter found employment in the famous Dobro making factory owned by The Dopyera Brothers and again images from the period would surface in later recordings of songs such as The Carpenter, on which he pays respects to those who create with their hands. He signed with Sunbury Music Publishers and joined a local bluegrass band of which an already established member, ´Skinny Denis´ Sanchez, would become legendary after Guy name-checked him in his song L.A. Freeway.

This song was written during the time Guy and Susanna decided they had to escape the smoggy and claustrophobic ´City of The Angels´ and head for Nashville, where they have now lived from 1971. Such a creative couple (Susanna, too, was a successful song-writer, and both she and Guy painted interesting works) naturally became a catalyst of artistic talents in the area.

When I was fortunate enough to meet and interview Guy in the nineteen eighties and nineties, he talked to me of great jam sessions involving the likes of Richard Dobson, Rodney Crowell and Townes, and also urged me to listen out for an emerging writer, Buddy Mondlock.

I listened and later noted that Buddy had co-written, with Joan Baez, the title track of her album, Play Me Backwards.

Guy Clark made his own recording debut in 1975 with an RCA release of the album Old Number One, although this was only after he had scrapped an entire album ´already in the can´ due to his personal dissatisfaction. However, most fans and critics still consider Old Number One to be Guy´s finest album. All the songs were self- penned, many being familiar. L.A. Freeway, with what my mate Pete Benbow called its ´pink guitar intro and world weary but defiant lyrics, had already been picked up by bands all over Britain, my own included, as it had been already recorded by Jerry Jeff Walker. Lines from the track loudly proclaim the Clarks´ reasons for leaving L.A. such as ´Here´s to you old Skinny Denis, the only one I think I will miss´ and the classic ´say goodbye to the landlord for me, the son of a bitch has always bored me.´

Whilst there was no love lost for the landlord then, although Guy often seemed to sing that line live with what have might have been an affectionate little chuckle, the album was nevertheless a home for characters for whom listeners would develop an abiding love.

There was barrel-riding Rita Ballou and there were Desperadoes Waiting For A Train ( in reality a young and imaginative Guy Clark and an old character from that childhood hotel) and the dying wino in Let Him Roll who all his adult life had loved a ´whore in Dallas.´ In fact Let Him Roll became a staple diet of my own poetry-slam performances in the UK along with Texas 1947and I always took the opportunity when performing to new audiences to diorect any not already familiar with Guy´s work to go and stand outside teir local record shops until they opened in the morning !

Whilst not my personal choice as his best album, this record also houses Instant Coffee Blues, that I do consider to be my favourite song of Guy´s.

This song examines the coldness and ultimate embarrassment of waking in bed next to a stranger after a one night pick up, and achingly captures the emptiness and loneliness of the characters as they shower and dress privately and grab breakfast separately and silently until comes the blessed time when ´she just has to go to work, and he just has to go.´

These partners are cleverly left un-named in the song, as if to emphasise that they don´t know each other´s names either, and the cold anonymity of their liaison.

The entire album featured some excellent fiddle from Johny Gimble and another interesting and soon to emerge name listed in Rock Record as having played on the album, that of Steve Earle !

The following year, 1976, saw RCA serve up some more Texas Cookin from master chef Guy Clark on his second album.

As on its predecessor we were introduced to fascinating and believable characters like The Last Gunfighter. This old man had lived through the days of guns and horses but had died in the, to him, unfathomable age of horns and automobiles. There was searing fiddle again in evidence on Virginia´s Reel and there was a beautiful, acoustic ballad of Broken Hearted People.

Guy and Susanna had collaborated on Black Haired Boy but it seems they arrived at their finished product by a circuitous route, as Guy explained to me in an interview – ´when Susanna wrote it, she was writing about me but I was writing about Townes and we didn´t become aware of that until we had finished the song.´

Not the most prolific of writers, Guy enjoyed the discipline of collaborating and explained to me that ´sitting and writing in a room by yourself all the time you kind of hit a brick wall after so long and sometimes writing with other people just keeps the juices flowing if you are having a dry spell yourself.´

A good number of Guy´s friends performed on this set including Hoyt Axton, Rodney Crowell and David Briggs of Bread, as well as Susanna who lent vocal support.

Despite the excellence of these first two releases Guy and RCA parted company, although he was allowed to buy the master of what was to have been the third release. At least four tracks from that purchase subsequently found their way on to the Warner Brothers´1978 eponymous release.

Initially, Guy was disappointed even with this first release on his second label, telling Pete O´Brien, ´for some reason it got overdone. We worked on it and worked on it and kind of lost sight of the natural energy of the music. It just got so overlaid until there was no spark left. To me, the songs are fine, its just the way we did ´em.´

Well, your critic here confesses that his listening is always lyric led and sometimes he doesn´t even notice the faults in arrangements, but I have to tell you that this album sounds fine to me. Lyrically there is less vivid description and less narrative than on the RCA releases, but most of the songs work as pure poetry. Without doubt this is my favourite album by the Texan songwriter, with Fools For Each Other and Comfort And Crazy precisely capturing my idea of a ´fine romance´, and a smooth version of Crowell´s Voila, An American Dream (also recorded by The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band). However, to O´Brien, Guy further suggested that Shade Of All Greens ´doesn´t even get close´ but, to me, the song works perfectly, recalling another of my favourites, Hoagie Carmichael´s Lazy Bones.

Maybe Guy´s own attitude to this album mellowed in time because, years later when I suggested to him that Shade Of All Greens was a very relaxed track, and that in fact I felt the whole album had a feeling of JJ Cale meeting Jimmy Buffett, he said ´yeh, that was good. I agree with that, there was some good stuff on that.´

Guy struck me as a hard task master not given to lightly suffering fools, though he seemed demanding, too, even in self- appraisal. It was to be three years until we distanced UK fans re-discovered Guy on record, down in the South East Of Texas. This album secured release only following a few traumas. Having finished the album, under the production of Craig Leon in Austin, and with the label already having had printed 25,000 album sleeves, the artist called a halt.

He described the recording as ´too slam bang´´saying there was not enough care taken with it. His friend, Rodney Crowell, took a listen and concurred, suggesting they head to L.A., recruit some musicians of empathy and recut the whole thing as quickly, and cheaply, but professionally, as possible. Two weeks later the album was ready !

Perhaps the highlight was New Cut Road, a tale of a son of early pioneers who tells his parents that even if they wish to continue travelling on, he doesn´t, and would rather settle down, plant roots and establish a township, — a parable which Guy compares with the offspring of twentieth century ´hippy´ parents growing up ´straight´!

The album also includes Heartbroke, recorded as a single, very successfully, by Ricky Scaggs as well as a collaboration with Rodney on The Partner That Nobody Chose and the quite brilliant Lone Star Hotel.

After this it took some while before the perfectionist that was Guy Clark to painstakingly gather ´ten good songs´ for what would be his third Warner Brothers collection and the fifth solo album of his career. This was optimistically entitled Better Days, and that title track was one of Guy´s strongest songs, a tender ´tomorrow is the first day of the rest of my life´ realisation by the tale´s female central character. There was also The Carpenter, an homage to skilled craftsmen from one of their number and The Randall Knife, a song so personal, about an implement that once belonged to his late father, that Guy thought he might never be able to bring himself to sing it on stage, although, fortunately for us, the song has become a concert favourite. Nevertheless, despite the excellence of the album, like previous Guy Clark recordings it was not a big seller, especially here in the UK, and was to be his last with a major label.

He was widely admired, but Guy´s cult following in the UK never quite opened out into the mainstream that carries commercial success and the logistics and economics of touring with a band in the UK were hopeless. In the states he played top line clubs and major events like the annual Kerrville Folk Festival, but although he regularly toured the UK as a solo performer it was almost invariably to smallish, if fervent, followings in tiny pubs and clubs.

I first saw him play at Buddies, a club in the North East with fellow American singer writer Jerry Jeff Walker, and to be honest I was so taken by the energy and brashness of Walker´s work that I almost overlooked Guy´s genius. ´

The next gig I caught, some years later, was that I mentioned at the top of this article when his beautiful picking, gentle humour and laconic wit held us all entranced. Two years on, I saw him play at The Winning Post in York where I was lucky enough to secure an interview with him. I found Guy to be thoughtful, but somewhat intimidating, and not very forthcoming, although I was later told he thought the interview had ´gone very well.´

It was to be another five years before the respected specialist Sugar Hill label issued Guy´s next album. What a revelation the 1988 issue of Old Friends proved to be. In a published review I observed that it ´finally realises the potential of the artist and lifts acoustic music to heights previously heard only in dream.´ The title track was a collaboration between Guy and Susanna and legendary Texan songwriter Richard Dobson and Throwing Good Love After Bad saw Clark co-writing with Vernon Thompson and Joe Henry, (formerly of The Jayhawks) who, along with Susanna, is name checked in a Jerry Jeff Walker song, Blue Mood, in which the writer reflects on friends who, one way or another, have all been ´screwed´ by the music industry!

I described Good Love After Bad as a ´potential pop hit´ and Come From The Heart as ´a code to live by´ (not then aware that it was actually pretty much Mark Twain´s code to live by !) and genuinely felt this album would open new frontiers for Guy, and that the session work from the likes of Sam Bush, Emmylou Harris, Vince Gill, Rodney Crowell and Roseanne Cash would surely earn the record some commercial success to accompany the critical acclaim always afforded to a Guy Clark album.

A couple of years later, after the album had caused barely a ripple on the ocean, Guy toured the UK again, this time sharing a bill with Peter Rowan, my hero John Stewart and Guy´s old mate Townes Van Zandt. The gig I caught by what should have been a dream package was a great disappointment, largely due to what I saw as an over enthusiastic spotlight-hugging performance from Guy, which surprised me as I had only ever heard fellow artists speak of his generosity of spirit. Nevertheless, he thrashed his guitar where once he had picked and swore and slurred through introductions that once had been witty and wry and seemed to have forgotten that, in the words of Come from The Heart, ´there´s such a thing as trying too hard!´

Then, another two years on, we had another new album from Guy, again on Sugar Hill. I played my review copy, and maybe jaundiced by memory of that performance on what I dubbed ´the fragile ego tour,´ gave it only one play, listened subjectively rather than objectively and dismissed Boats To Build as a collection of lightweight songs. WHAT??

I felt there were too many songs, such as Watermelon Dreams and Doctor Doctor, the likes of which had been used sparingly to lighten the tones of previous albums. Individually, such songs can be effective but to my mind there were just too many to support this album. Then, Wally Whyton played a track on his BBC Radio 2 country programme. He somewhat berated me on national radio for a review of mine that had just been published and opined that whatever I had said about it, that this may just be Guy Clark´s best ever album.

Well, Wally was no wally so I listened again. Whilst I still don´t think he was quite right, I fully accept that the broadcaster´s first reaction was far more accurate than mine had been. There´s a loose almost jam-session feel about the set, which features again Emmylou and Sam Bush with Jerry Douglas on dobro.

Baton Rouge is an excellent opener written with J.C. Crowley and the title track, by Guy and Vernon Thompson, is exquisite. There´s a touching memory of something Ramblin´ Jack Elliott Said written by Guy with Richard Leigh, best known for Don´t It Make My Brown Eyes Blue, but it is another offering from these same collaborators that is the stand-out track on an album that runs for only thirty five minutes. I Don´t Love You Much Do I carries gorgeous female backing vocals and would highlight any album in this genre.

Many Guy Clark songs have spawned successful cover versions, of course, including, somewhat disconcertingly, Bobby Bare´s version of New Cut Road which he took to number one in the USA country charts after Guy had ignored his own label´s advice that he himself should release the track as a single.

Other cover versions include Jerry Jeff Walker´s interpretation of Desperadoes Waiting For A Train, which David Alan Coe also recorded. Johnny Cash recorded an offering of The Last Gunfighter, and of course there were several I mentioned earlier in this article. Kathy Mattea placed Come From The Heart on one of her albums and Richard Dobson recorded So Have I, his writing collaboration with Guy, as an album title track.

This enigmatic Guy is perhaps not sufficiently prolific to be termed a great songwriter, but he is indisputably a writer of great songs! When asked by Pete O´Brien (for The Omaha Rainbow) how he would respond if a gunman threatened to fire at him unless Guy named his favourite of his own compositions the song-writer said he would actually simply reply ´shoot.´

Given that this journalistic has developed cowardice into an art form I would immediately name Instant Coffee Blues, oh no, Texas 1947, wait, wait, Shade Of All Greens or, no,.. Come From The Heart, hang on, maybe Boats To Build, no I´ve got it, I´ll say……BANG !!!

This article was compiled from reference to Detour issue 2 / Omaha Rainbow issue 30 / Music Master Country Catalogue / Rock record by Terry Hounsome (published Blandford Press) / The Illustrated Encyclopeadia Of Popular Music (Penguin) / Personal interviews with Guy Clark by the author.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!