BILLIE HOLIDAY: A POET´S MUSE part 4 of the inaugural S & D Joined Up Jazz Festival in association with Hot Biscuits

BILLIE HOLIDAY: A POET´S MUSE

part 4 of the inaugural S & D Joined Up Jazz Festival

in association with Hot Biscuits

by Norman Warwick

Billie Holiday’s vocal delivery that made her performances recognizable throughout her career, many years after her death provided a muse for one of my favourite British poets, James Nash. A Sidetracks & Detours piece about his career remains in our poetry archives.

James Nash wrote A Bench For Billie Holiday as a sonnet and it became the title piece of a collection of some seventy odd of such pieces. the work spoke for all of us who somehow hear music in our heads whenever and wherever we sit and relax and is, itself, a quite beautiful work.

Billie´s improvisation compensated for lack of musical education. Holiday said that she always wanted her voice to sound like an instrument and some of her influences were Louis Armstrong and the singer Bessie Smith. Her last major recording, a 1958 album entitled Lady in Satin, features the backing of a 40-piece orchestra conducted and arranged by Ray Ellis, who said of the album in 1997:

photo billie with ray ´I would say that the most emotional moment was her listening to the playback of I’m a Fool To Want You. There were tears in her eyes … After we finished the album I went into the control room and listened to all the takes. I must admit I was unhappy with her performance, but I was just listening musically instead of emotionally. It wasn’t until I heard the final mix a few weeks later that I realized how great her performance really was.´

Frank Sinatra was influenced by her performances on 52nd Street as a young man. He told Ebony magazine in 1958 about her impact:

´With few exceptions, every major pop singer in the US during her generation has been touched in some way by her genius. It is Billie Holiday who was, and still remains, the greatest single musical influence on me. Lady Day is unquestionably the most important influence on American popular singing in the last twenty years.´

Eleanora Fagan (April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959), became professionally known as Billie Holiday, (right) an American jazz and swing music singer with a career spanning 26 years. Nicknamed Lady Dayby her friend and music partner Lester Young, Holiday had an innovative influence on jazz music and pop singing. Her vocal style, strongly inspired by jazz instrumentalists, pioneered a new way of manipulating phrasing and tempo and she became known for her vocal delivery and improvisational skills.

After a turbulent childhood, Holiday began singing in nightclubs in Harlem, where she was heard by producer John Hammond, who commended her voice. (see recent sidetracks & detours piece Bessie Smith: Empress Of The Blues) Billie Holiday signed a recording contract with Brunswick in 1935. Collaborations with Teddy Wilson yielded the hit What A Little Moonlight Can Do, which became a jazz standard. Throughout the nineteen thirties and forties, Holiday had mainstream success on labels such as Columbia and Decca. By the end of that latter decade, however, she was beset with legal troubles and drug abuse. After a short prison sentence, she performed at a sold-out concert at Carnegie Hall, but her reputation deteriorated because of her drug and alcohol problems.

She nevertheless remained a successful concert performer throughout the fifties with two further sold-out shows at Carnegie Hall. Because of personal struggles and an altered voice, however, her final recordings were met with mixed reaction but still achieved some commercial successes.

Her final album, Lady In Satin, was released in 1958 but Holiday died of cirrhosis on July 17, the following year. She won four Grammy Awards, all of them posthumously, for Best Historical Album. She was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1973.

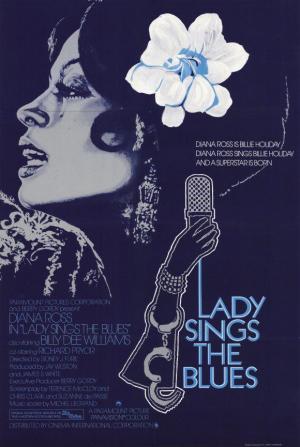

Lady Sings the Blues, a film about her life, starring Diana Ross, was released in 1972. Hers is the primary character in the film and the play entitled Lady Day At Emerson’s Bar And Grill in which Bessie´s character was originated by Reenie Upchurch in 1986 and was played by Audra McDonald on Broadway and in the film. In 2017, Holiday was inducted into the National Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame.

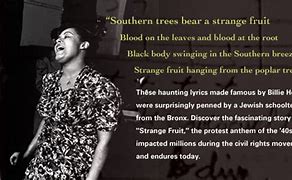

Holiday was recording for Columbia in the late 1930s when she was introduced to Strange Fruit, a song based on a poem about lynching written by Abel Meeropol, a Jewish schoolteacher from the Bronx. Meeropol used the pseudonym Lewis Allan for the poem, which was set to music and performed at teachers’ union meetings. It was eventually heard by Barney Josephson, the proprietor of Café Society, an integrated nightclub in Greenwich Village, who introduced it to Holiday.

She performed it at the club in 1939, with some trepidation, fearing possible retaliation. She later said that the imagery of the song reminded her of her father’s death and that this played a role in her resistance to performing it.

The lyric replicates a black and white photo, printed in the press, a window to a tragic and unforgivable event. Four black teens were arrested for the alleged rape of a young white woman, Mary Ball, and murder of a young white man, Claude Deeter. Their names were James Cameron, Abram Smith, Thomas Shipp, and Robert Sullivan. Sullivan was released after a brutal interrogation while the other three were forced to spend the night in jail.

In the middle of the night a mob arrived and broke into the cells. After they were beaten to the brink of death, Thomas Shipp was originally hung from the bars of the prison. Abram Smith was dragged to the nearest tree and hung. When he struggled to get free from the noose, he was taken down, stabbed, and both of his arms were broken before he was tied back into the tree. They moved Thomas’s body to string him up in the tree as well.

The last boy, James Cameron, was about to be hung when someone pretested that he was too young and had nothing to do with the murder or rape. The mob released him. James was relocated to another prison and, during trial, Mary Ball admitted that she had not been raped. Although it was proven that James had nothing to do with the events, he spent four years in prison. Later in his life, working as a black and lynching activist, he founded America’s Black Holocaust Museum. He died in 2006 at the age of 92.

The poem, Strange Fruit, was inspired by that picture of the lynching. Soon afterwards the poem gained popularity through Billie Holiday’s sung version, although other famous artists like Nina Simone have also covered the song. More recently, India Arie recorded it on her album Songversation and Kanye West sampled Nina Simone’s version on his tracks ´Blood on the Leaves” and it’s also referenced in his track ´New Slaves´.

Strange Fruit, I guess, is not a song we are meant to like and Billie Holiday sings it with no false note or tone whatsoever, as if to remind us that this is not a song meant to be liked. It’s supposed to be disturbing, just as the subject is disturbing. There is no beauty in bodies hanging from trees. Referring to them as fruit implies that this was a common sight and that to some parts of society was deemed acceptable.

We need to look back at our history and acknowledge the horror of it. This is a poem worthy of remembrance, and the song still further cements the memory in our hearts, as the new social movement seeks to disentangle itself from misappropriation and achieveç its aim of ensuring that, really Black Lives Matter.

For her performance of Strange Fruit at the Café Society, Billie had waiters silence the crowd when the song began. During the song’s long introduction, the lights dimmed and all movement had to cease. As Holiday began singing, only a small spotlight illuminated her face. On the final note, all lights went out, and when they came back on, Holiday was gone.

Holiday said her father, Clarence Holiday, was denied medical treatment for a fatal lung disorder because of racial prejudice, and that singing Strange Fruit reminded her of the incident.

´It reminds me of how Pop died,´ she later wrote in her autobiography, ´but I have to keep singing it, not only because people ask for it, but because twenty years after Pop died the things that killed him are still happening in the South.´

When Holiday’s producers at Columbia found the subject matter too sensitive, Milt Gabler agreed to record it for his Commodore Records label on April 20, 1939. Strange Fruit remained in her repertoire for 20 years. She recorded it again for Verve. The Commodore release did not get any airplay, but the controversial song sold well, though Gabler attributed that mostly to the record’s other side, Fine And Mellow, which was a jukebox hit.

´The version I recorded for Commodore,´ Holiday said of Strange Fruit, ´became my biggest-selling record.´

Strange Fruit was, indeed, the equivalent of a modern day top-twenty hit in the in the nineteen thirties and Holiday’s popularity increased after the record´s success. She received a mention in Time magazine.

´I opened Café Society as an unknown,´ Holiday wrote in her memoir. ´but I left two years later as a star. I needed the prestige and publicity all right, but you can’t pay rent with (that alone).´

She soon demanded a raise from her manager, Joe Glaser. Holiday returned to Commodore in 1944, recording songs she made with Teddy Wilson in the 1930s, including I Cover the Waterfront, I’ll Get By, and He’s Funny That Way. She also recorded new songs that were popular at the time, including, My Old Flame, How Am I to Know? I’m Yours, and I’ll Be Seeing You, a number one hit for Bing Crosby. She also recorded her version of Embraceable You, which was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2005.

In the nineteen fifties, though, Holiday’s drug abuse, drinking, and relationships with abusive men caused her health to deteriorate. She appeared on the ABC reality series The Comeback Story to discuss attempts to overcome her misfortunes but her later subsequent recordings showed the effects of declining health on her voice, as it grew coarse and no longer projected its former vibrancy. Callous though it may send there are some fans, and I include myself among their number who found this new vocal tone very affecting.

Holiday’s autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, was ghost-written by William Dufty and published in 1956. Dufty, a New York Post writer and editor then married to Holiday’s close friend Maely Dufty, wrote the book quickly from a series of conversations with the singer in the Duftys’ 93rd Street apartment. He also drew on the work of earlier interviewers and intended to let Holiday tell her story in her own way.

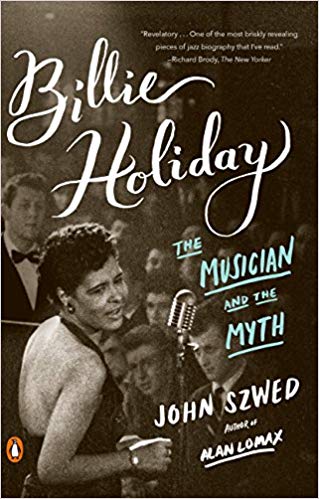

However, in his 2016 Jazz Book Of The Year, Billie Holiday: The Musician And The Myth, John Szwed argued that Lady Sings the Blues is a generally accurate account of her life, and that co-writer Dufty was forced, by the threat of legal action, to water down or suppress some of his material.

According to the reviewer Richard Brody, ´Szwed traces the stories of two important relationships that are missing from the book—with Charles Laughton, in the 1930s, and with Tallulah Bankhead, in the late 1940s—and of one relationship that’s sharply diminished in the book, her affair with Orson Welles around the time of Citizen Kane.´ To accompany her autobiography, Holiday released the LP Lady Sings The Blues in June 1956. The album featured four new tracks, Lady Sings the Blues, Too Marvellous for Words, Willow Weep For Me, and I Thought About You as well as eight new recordings of her biggest hits to date.

The re-recordings included Trav’lin’ Light, Strange Fruit and God Bless the Child. A review of the album was published by Billboard magazine on December 22, 1956, calling it a worthy musical complement to her autobiography.

´Holiday is in good voice now,´ wrote the reviewer, ´and these new readings will be much appreciated by her following.´

Strange Fruit and God Bless The Child were called classics, and Good Morning Heartache, another reissued track on the LP, was also noted favourably.

On March 28, 1957, Holiday married Louis McKay, a mob enforcer. McKay, like most of the men in her life, was abusive.[91] They were separated at the time of her death, but McKay had plans to start a chain of Billie Holiday vocal studios, on the model of the Arthur Murray dance schools. Holiday was childless, but she had two godchildren: singer Billie Lorraine Feather (the daughter of Leonard Feather) and Bevan Dufty (the son of William Dufty).

By early 1959, Holiday was diagnosed with cirrhosis. Although she had initially stopped drinking on her doctor’s orders, it was not long before she relapsed. By May 1959, she had lost 20 pounds (9 kg). Her manager Joe Glaser, jazz critic Leonard Feather, photojournalist Allan Morrison, and the singer’s own friends all tried in vain to persuade her to go to a hospital. On May 31, 1959, Holiday was taken to Metropolitan Hospital in New York for treatment of liver disease and heart disease. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics, under the order of Harry J. Anslinger, had been targeting Holiday since at least 1939. She was arrested and handcuffed for drug possession. As she lay dying, her hospital room was raided, and she was placed under police guard.] On July 15, she received the last rites of the Roman Catholic Church. She died at 3:10 a.m. on July 17, of pulmonary edema and heart failure caused by cirrhosis of the liver. She was 44.

In her final years, she had been progressively swindled out of her earnings, and she died with US$0.70 in the bank. Her funeral Mass was held on July 21, 1959, at the Church of St. Paul the Apostle in Manhattan. She was buried at Saint Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx.

When Holiday died, The New York Times published a short obituary on page 15 without a by-line. She left an estate of $1,000 and her best recordings from the ’30s were mostly out of print. Holiday’s public stature grew in the following years. In 1961, she was voted to the Down Beat Hall Of Fame, and soon after Columbia reissued nearly one hundred of her early records. Diana Ross’ 1972 portrayal of Holiday in Lady Sings The Blues was nominated for an Oscar and won a Golden Globe. Holiday was posthumously nominated for 23 Grammy awards.

As recently as June 25th 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Billie Holiday among hundreds of artists whose material was reportedly destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire. Today, though, a biographical drama film The United States vs. Billie Holiday starring singer Andra Day portraying Holiday is set for imminent release.

Though her musical career seems a success story, Holiday’s personal life was tumultuous. She was heavy into alcohol and heroin, which, along with her tempestuous love life, often got in the way of her career. Nevertheless her interpretations of blues and jazz standards remain the quintessential versions to this day, and her unique voice has inspired countless singers from Ray Charles to Amy Winehouse.

Paste on-line magazine some while ago posted a piece on Billie and commended what they thought were her top five songs, and we reproduce their list here below with their validations for the choices. We all have a few judges and critics we place our trust in and these days mine all seem to write for Paste. Why not check out their site one day time soon, over a cup of coffee, with these songs playing in the background?

We offer them to you in the ascending order beloved of tv game shows !

Lover Man: This track has the pained echoes of Billie Holiday’s troubled love life. In 1941, Holiday married James Monroe, a violent playboy who abused her and was said to have only married her to ride on her lucrative coat-tails. It was Monroe that introduced Holiday to opium. Later, after her marriage tanked, another no-good musician she was seeing, Joe Guy, got her hooked on heroin. Thus, this song seems to parallel her own struggle to find a true “lover man” who treats her right. Though she recorded the song several times over her career, it’s this live version from 1958, only a year before her death, that is particularly haunting.

Easy Livin’: This is an earlier recording of Holiday’s from 1937, when she was not the star out front, but part of the band. In fact, Holiday was tapped to sing vocals in front of Teddy Wilson and his Orchestra for this session, which included Buck Clayton on trumpet, Buster Bailey on clarinet, Lester Young on tenor sax, Freddie Green on guitar, Walter Page on bass, Jo Jones on drums, and Wilson himself piano. Wilson’s strident lines drive this track, along with the guitar playing of Green (who later became a permanent member of the Count Basie Orchestra). Holiday’s spacious vocals, however, float over the top of their playing, creating a mood straight out of a 1920s speakeasy.

Blue Moon: One of the most important tracks off Billie Holiday Sings is this 1952 version of Blue Moon. This song is usually associated with Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, but actually, the song was around decades before the film, being passed between vocalists of the day. Blue Moon is from the famous song-writing pair Rodgers and Hart, and Holiday does justice to the levity that seems pervasive in their musicals. She also takes some tasty liberties with the melody that work especially well when paired with her coquettish delivery.

Solitude: Holiday recorded this track several times over her career, for Columbia, Commodore, and Decca Records. Later it also appeared on a 1952 Clef Records reissue that was named after the song. A Duke Ellington original, Holiday’s version is recorded with heavy-weight jazzers—pianist Oscar Petersen and bassist Ray Brown, with an intro the great guitarist Barney Kessel. Many other singers have recorded this track, from Ella Fitzgerald to Etta James, but this song seems inextricably connected with Billie, whose minimalist phrasing and moody vocal timbre seemed to do it justice.

Strange Fruit: This track has to be at the top of the list; it’s that influential. One of the first racism protest songs to be recorded in popular music, 1939’s Strange Fruit is based off a poem written by Abel Meeropol. Holiday sang the song for the first time at Café Society in Greenwich Village, which was the first integrated nightclub in New York City. With the song’s blatant indictment of racism in the American South, it’s said that Holiday was afraid of retaliation every time she sang the song. Not to mention, no record label would touch it. Eventually, Milt Gabler put the track out on Commodore records after Holiday’s a cappella performance of it brought him to tears. Despite being aware of the danger of singing a song like this as a black woman, Holiday sings Strange Fruit with unwavering bravery and intention, her emotive voice bolstering its timeless meaning.

This article was written by Norman Warwick, owner and editor of Sidetracks & Detours, and a weekly columnist for Lanzarote Information

The Sidetracks & Detours inaugural Annual Joined Up Jazz Celebration in association with Hot Biscuits reaches the end of its first week tomorrow as we continue with our next daily post. Club Scene Seen is an article compiled by all four of our Joined Up Jazz Journalists, Norman Warwick, Steve Bewick, Gary Heywood-Everett and Susana Fondon and will take a world wide look at jazz venues and artists.

Don´t forget you can hear Gary and Steve Bewick presenting the Hot Biscuits jazz Programme on www.fc-radio.co.uk

You will also find regular interviews by Susana conducted with musicians of all genres in her articles on Lanzarote Information.

We are grateful to Jazz In Reading, Jazz North and Ribble Valley jazz And Blues for their kind support and look forward to bringing you further details in the weeks to come of the excellent work they all do for the jazz community.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!