HEAR THE VOICE OF THE BARD by Michael Higgins

HEAR THE VOICE OF THE BARD

by Michael Higgins

There is something unreal about life and living it. There is nothing more real than experiencing life’s joys and imaginings. But nothing is more unreal than its despair and misunderstandings. Language is both a guide and a deceiver.

At the age of eight I had a very real brush with the Welsh Language. Our next door neighbour was Welsh and her Welsh speaking nephew from North Wales used to stay with her during the holidays. We commingled Welsh and Northern English dialect during play. By coincidence my school teacher was also Welsh and she taught us to sing the English words to Ar Hyd y Nos (All through the Night) before we left school at the end of the day. That year the BBC briefly broadcast a Welsh language programme at tea- time and she recommended we all watch it.

The first Welsh word I picked up was ‘pwy?’ (who?) and my teacher taught us how to use it. So the who? as both question and answer was the start of grown up journey for me through that year’s holiday in north Wales, along with the kindness shown to me by my teacher, so worried about my struggles with school arithmetic that she came to our house to coach me. It went with our emigration to Toronto the following year, along with the book she gave me to read on the way.

Canada increased in me what the Welsh call hiraeth a yearning for something – often for home and family in England, often for that great other we call spiritual fulfilment. I followed a great romantic idea in our family that my great grandmother (a Griffith) was Welsh, and a haunting folk song from the 1945 film The Corn Is Green, starring Bette Davis (herself of Welsh descent) was important.

The song, Dacw’n Gariad i (Yonder Is My Love), which the homecoming miners sing after a long day underground, enticed me for years. It tells of a love-struck swain watching his true love as she gathers in the orchard, the farmhouse door remains open, and the harp sits waiting for someone to play it.

Toronto then held Canada’s largest Welsh settlement and Dewi Sant (St David’s) Welsh United church held Welsh language lessons and services open to all, including English- Canadian boys. And a visiting English uncle brought me a much treasured anthology of Welsh verse which I read throughout my dropout bohemian days in Toronto’s, and Canada’s largest Hippy Settlement, Yorkville. A bohemian life there spurred a pursuit of the hidden underworld of philosophy, verse and song, embracing medieval literature along with my hiraeth. I gained access to the Myvyrian Archaeology of Wales (published 1801-7) containing supposed ancient Cambrian poetry and gnomic verse, through my friend and fellow poet, Ian Young, who then worked at the University of Toronto Library.

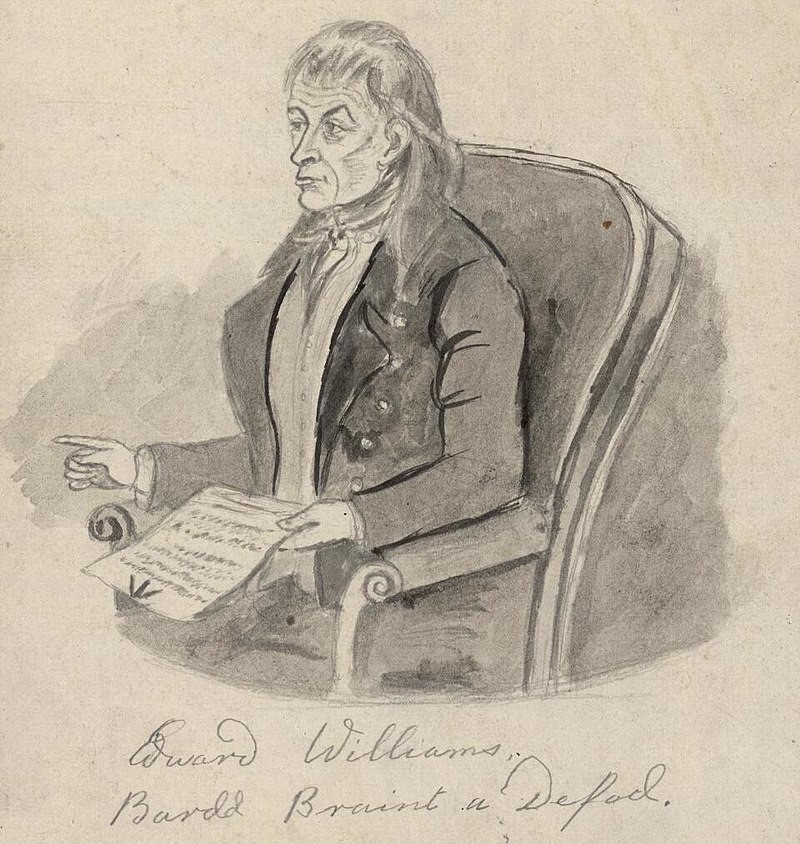

This brought me into contact with the writings of Iolo Morganwg (Iolo of Glamorganshire), one of its compilers. Through his own hiraeth for lost Welsh manuscripts and traditions, Iolo (1747-1826), whose given name was Edward Williams, has now gained the unfortunate reputation of being outed as literary forger, along with the English poet Chatterton, James Macpherson, and to a lesser degree Bishop Percy and his Reliques. Like Percy, Iolo is reckoned to have ‘improved’ many of the old manuscripts he claimed to have collected from old hall libraries all over Wales.

Iolo’s public persona is responsible for ‘reviving’ the Welsh Gorsedd (throning of bards) and Eisteddfod (poetry and music session sitting) with its pseudo- Druid ritual and dress in a ceremony attended by Welsh Exiles in London in 1792. He also revived, or invented as some would have it, the whole spirit of ancient Druidry as a folk belief, involving priestly bards, poetry, song, and that lonely Welsh harp that waited so long for a nationalist harpist to pluck its melodious strings. Hence the white robes, the Arch Druid, the Throning of the Bard and the whole theatrical heart of Wales pitched against English language hegemony and English all-invasive cultural thought. Modern Wales is now replete with annual Eisteddfodau, where poetry and music are celebrated and new bards honoured.

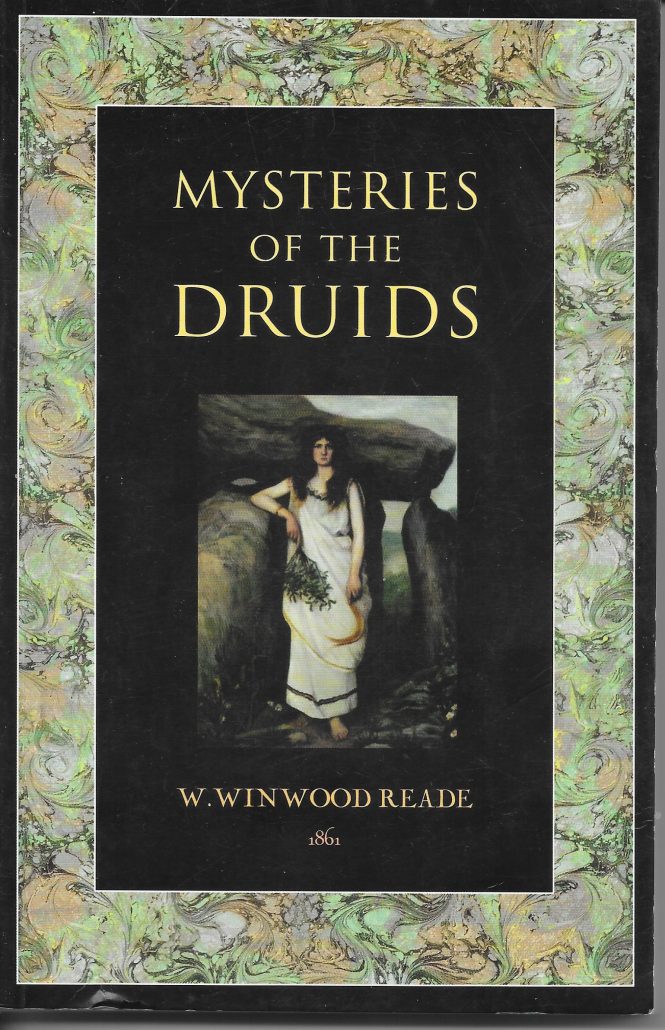

Photo William Winwood Reade But romanticism treads perhaps too light a step. William Winwood Reade, in his 1861 book The Veil of Isis or Mysteries of the Druids proposed a different tack, warning that Druidism was outwardly a pantheistic theocracy of philosopher-priests, hymnodic harp playing bards, and Ovate acolytes that have helped to distract not only Western thought but also the very rituals of the Roman Catholic Church and that other secret society, Freemasonry. And woe to betide, the burgeoning Oxford Movement of the day was threatening to distract the Church of England with Druidism as well. True Druidism worshipped the One God in the open air, and ostensibly only ‘honoured’ or at least tolerated lesser beings such as minor gods of the landscape. But their pureness was marred by human sacrifice and popular idolatry. The book is a good read for all aspiring churchgoers loving a good tale of all-pervasive heathen superstition in ritual and folklore but modern archaeology douses both Winwoode Reade’s and Iolo Morganwg’s belief that fallen Druid’s practised the dark arts at stone monuments such as Stonehenge and wore white robes whilst clutching mistletoe. I loved Winwood Reade’s book but then I loved Morganwg as well. Not so sure about the Archaeologists. Still wary about the Bards.

Having returned to northern England permanently just before my 24th birthday I brought the romantic notions of Flower Power Yorkville back with me along with my pseudo-Welshness in some form or other. And Iolo was part of it- as was my other yearning back to Lancashire dialect and my by then also pseudo-English memories. I was grown up, my relatives much older, and the hum-drum unreal life of making a living impinged on the reality of Iolo’s world and that of the equally romantic notions of a fading hippy age. I have since revisited both Canada and Wales many times with a more chastened romantic heart. Indeed Hippy Yorkville is now an upmarket boutique and art consumerama swept clear of all its ghostly corner poets and cafe philosophers.

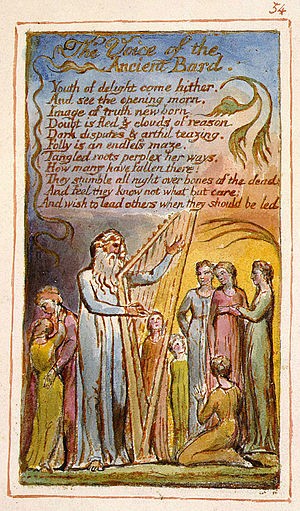

That is until a few weeks ago when Ian Young and his partner Wulf, sent me a link to a modern Druidry website entitled Barddas, the Welsh word for both poetry and all poetics, and the title of one of Iolo’s supposed theological manuscripts which infers a more priestly and prophetic calling. The idea of white robed and bearded bard declaiming prophecy from his harp was a popular one in 18th century literature and was much used by William Blake (1757-1827) in his ‘prophetic books’. But Blake also saw the bard of old as a sometime threatening figure and something to be feared. The author of the Barddas site (https:/barddas,org/about), strangely using the Russian pseudonym of Bogatyr, professes to be a practising Welsh speaking Druid in the spiritual sense, having progressed from Budhism and Daoism. He praises Iolo Morganwg for his imagination in using his own insights to give Wales a bulwark of high romanticism with which to fight English imperialism. The writer also spends much time admonishing modern English pagans who aspire to learn from Druid philosophy and wisdom.

He suggests they follow old English gods Woden and Thor and Anglo Saxon gods instead, and leave Welsh esotericism to the Welsh. So much for Christianity then, of which Iolo was an eccentric and flamboyant outrider. Indeed Iolo has been counter-charged with part- Christianising pagan Druidism for his own ends.

I remarked to Ian that this Bogatyr chap seems like the ‘Little Waleser’ who want his culture, language and spiritual sense to be kept secret and who bemoans outsiders (such as the dreaded English) even trying to speak the Welsh language. And I have encountered a few like him in my efforts to practise my extremely rusty, and antiquated, Canadian Welsh on the inhabitants of North Wales. Like so many new religious sects hierarchies and proprietorial jealousies abound. How different from my Welsh proselytisers, schoolteachers and clergymen only happy to spread Welshness in all its forms.

Historians point out that all Welsh mythology comes from medieval manuscripts and the medieval world view.

This has not stopped antiquarians probing the Welsh ‘fairy tales’ such as the Myfyrian Achaiology and the Mabinogion for evidence of old gods and old religions. And the power of the Druids, ostensibly stamped out in Roman times, was soon found to be alive and well in the form of Wales’s itinerant court musicians. Iolo Morganwg’s promotion of modern Druidism as a national expression of spirit has indeed promoted Druidism as a new religion and indeed new benevolent societies exemplified in the old Ancient Order of Druids so prevalent in the early 19th century. But he is no different than that other promoter of Welsh culture- Geoffrey of Monmouth, accused of inventing the entire King Arthur saga to counter English cultural claims to be ‘British’ in the 12th century. Before Geoffrey, Arthur was a sparsely mentioned semi- mythological chieftain character in ancient poetry called Triads. Henry II claimed Arthur for England by wondrously discovering his supposed grave at Glastonbury. But who was the winner here – Wales, England, or Britain? Some might argue it was the world and world literature. And Iolo Morganwg was later to be accused of forging some of these Triads too.

Photo And as for Druidism there is no greater entwining of ancient belief and Christianity than the subsequent myth that supposed Druidry was monotheistic and grounded in Hu Gadarn (Hu the Mighty spirit) and the schooling of a young boy Jesus of Nazareth in Druidic lore at Glastonbury and other places visited by his tin trading uncle Joseph of Arimathea. After Jesus’s crucifixion and burial in Joseph’s own tomb back in Judea, Joseph returns in this myth to Britain with the Holy Grail to rest at Weary-All- Hill to plant his staff as the Glastonbury thorn. Hence William Blake’s hymn:

‘And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountains green

And was the Holy Lamb of God

On England’s pleasant pastures seen…….’,

later set to music by Sir Hubert Parry and freshly titled by him ‘Jerusalem’. Blake does not answer the question he sets but does ask us to act as if the answer were yes.

Indeed the proclaimed motto of Bardism and Druidry is ‘Truth against the World’ (Gwir yn erbin y byd) and the bard (bardd), that Welsh word borrowed to clothe the greats from Shakespeare to Dylan Thomas et al, lives hopefully as an exponent. Mere versifiers do not ordinarily get to be called bards, but even that distinction escapes notice in the great desire to honour the art. The old English equivalent was scop (a shaper) which has become in Scottish English a maker. But the Welsh word has won out.

The gatherings at which I often recite and sing in the Baum public house, Rochdale, Lancashire, are called ‘Bards from the Baum’ and no doubt there are some aspiring greats gathered here among the not quite yet so greats. And I do occasionally sing Blake’s Jerusalem to my own melody which I composed all those years ago in Yorkville. Parry’s hymn version and tune were not so well known there and I was not aware of a sung version until it was too late. But then William Blake often composed tunes for his poems which he sang at gatherings. And would he have liked either Parry’s or my version? Indeed would I have liked his melodies had they not all been lost with his passing? My heart yearns that I would.

Like Iolo Morganwg, poets work in a cloud of haphazard inspiration or awen, where imagination is far more important than mundane fact. Bards create whole worlds of sung creation for us to believe or disbelieve but nonetheless get carried away on a tide of yearning.

For me that yearning for my great grandmother’s Welshness has got lost in my cousin Julie’s genealogical research that petered out in the Northern English county of Westmorland in the 19th century. This does not mean there is not a Welshness somewhere if we go back far enough, but as yet not enough proof rewards family imaginings. Yet despite the writer of the Barddas website perhaps there is still hope for Englishmen and all others who live a life of poetry and song.

And hope for the lapsed philistines too. Perhaps all poets and musicians can do is create a world that others recognise and yearn for.

As Blake exhorts:

Here the voice of the bard!

Who past, present and future sees;

Whose hears have heard

The Holy Word

That walked among the ancient trees,

Calling the lapsed Soul,

And weeping in the evening dew;

That might controll

The starry pole,

And fallen, fallen light renew!

And if that isn’t Druidry, what is? Pwy all ddilyn hynny? ( Who can follow that?) Pwy?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!