ON THE PATH OF JONI MITCHELL

Norman Warwick follows others

Travelling ON THE PATH OF JONI MITCHELL

Ann Powers may be the most obvious selection for an author to write a 400-page biography about Joni Mitchell. The NPR music critic has worked for decades telling the stories of female musicians, from PJ Harvey (left) to Beyoncé. Her work has been absolutely seminal, cementing women’s place in the worlds of rock and roll and popular music, and their place in the game of rock criticism.

Even still, Powers remains believably surprised that she ended up embarking on a journey through the 80-year-old singer and songwriter’s life. She reveals early on in Traveling: On The Path of Joni Mitchell that she was never quite able to connect with Joni Mitchell, something about her glacial beauty and honeyed soprano kept Powers at a distance for many years.

Sure, she was able to acknowledge the importance of Mitchell’s work, but never felt at home claiming it as her own. On the surface, Mitchell seemed too clean. Traveling, among other things, works to show the mess of Joni Mitchell—to dismantle the folk-princess myth that characterized Powers’s first encounters with Mitchell’s oeuvre.

Biography itself, according to Powers, “was invented to celebrate heroes—or really to organize such creatures into being.” Powers isn’t interested in creating a hero of Mitchell. Rather, she tries to get to the heart of how legends come into being, how stories are told, and who has the right to tell them. all while working through her own version of a Joni Mitchell legend. The story that follows is as much a practice as it is the narrative itself, as much Powers’ traveling through her own history as Powers troubles the easy narratives: that Polio was the impetus for Mitchell’s turning to art; that Blue is an album of sadness alone; that Joni was a sad girl, a girl of solitude; that she was a jazz musician; that she wasn’t a jazz musician; that she ever did or did not want to be a mother. It’s a careful balancing act and one that Powers executes well. Powers understands biography as a process of simultaneous reduction and expansion. She knows that even 400 pages cannot come close to coloring in the full life of any person, yet she makes it her aim to expand upon the original Joni Mitchell myth that she was first confronted with. She seeks the words of those who spent time around Mitchell, from David Crosby and Graham Nash to Brandi Carlile and once-husband Larry Klein, but not without the diligence of a good critic.

“It’s fairly impossible to gain new insight about Mitchell from a conversation with [Graham] Nash at this point,” she writes, but she opts to have the conversation anyway, integrating Nash’s enchanted words to interrogate the dominant narrative. The only conversation Powers forgoes is that with Mitchell herself, deemphasizing proximity as a means of reaching toward some personal objectivity.

The narrative that Powers creates functions as a travelogue on the open road; much like music, it has no choice but to unfold in time. Though its medium is chronological in nature, it is never a forced chronology. Powers moves as close in time with Joni as she can, as close as any of us can to telling a linear life story, especially one of an artist who was committed to constantly revisiting, rewriting, and re-reflecting on her pasts. As lives repeatedly connect and harken back to themselves, Powers plants the seeds of what is to come as she moves alongside Mitchell. She deftly anticipates the questions her readers and sceptics may pose at any given point along the journey, unafraid to tell us I know, but we aren’t there yet. Round and round in the circle Powers does get to everything eventually, even the thornier parts of Mitchell’s legacy, without shying away from the moments when the artist was firmly and unequivocally in the wrong. She dedicates a chapter to Mitchell’s appropriation of Black culture, culminating in the moments when Mitchell donned blackface on the cover of her 1977 Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, as well as at costume parties and gatherings around the time of the record’s release. She’s careful not to contextualize Joni’s self-proclaimed Black alter ego Art Noveau, but is also careful not to gloss over it.

“Her creation of Art Nouveau did involve violence,” Powers writes, “The theft part of appropriation always does.” She invites Black critic Miles Greer into Traveling’s conversation about Art, a move that feels less like a way of Powers assuaging her middle-class white guilt and more a way of offering access to one of the many perspectives she cannot possibly hold herself.

Alongside Joni’s motion through Travelling, Powers finds it impossible not to mention her own. When discussing Mitchell’s reconnection with Kilauren, the daughter she had put up for adoption decades earlier, Powers reflects on her journey as an adoptive mother; when taking her readers through Joni’s Laurel Canyon Boys Club, Powers remembers the ways that she once tried to charm the boys in her confidence through tarot cards and Nick Drake records. She brings us through Zoom therapy into her marriage to Eric Weisbard, all in a way that doesn’t ever feel forced. It feels inevitable.

Jazz is a centerpiece of Powers’ storytelling—it appears before 1979’s Mingus, before she details Joni’s complicated tug-of-war with the jazz fusion scene of the late ’70s. In a section entitled Her Kind of Blue, Powers attempts to find a fresh point of entry for talking about Mitchell’s 1971 masterpiece Blue, which she discovers in Miles Davis, his Kind of Blue enacting a similar emotive minimalism to her kind. It is in the chapter on Blue where we find some of Powers’s most utterly beautiful lyrical writing. She lingers in the floating waves of “River,” finding profundity in one of the record’s most simple lyrics: “I’m so hard to handle / I’m selfish and I’m sad.”

“Selfish and sad circle around each other,” Powers writes. “How, the song asks, can a woman survive the grief her life creates without it burying her? How can I be sad and a good person, a good woman too? Are these the same circles that Powers insists come to characterize Joni’s 1976 Hejira—those “loops within loops, within loops. Always moving, never landing”?

Powers understands the dance that a critic often feels she must do with her subject: to write about an idol is to seek their real or imagined approval. She introduces herself at the beginning as a critic, not a biographer, a role she reprises at the very end of the book to discuss Mitchell’s more subdued return to the public stage. “What is criticism but a balancing act between the head and the heart?” she writes. “Being a critic is like being an artist, to love in a way that is as careful as it is passionate.”

Powers meets the challenge that Mitchell issues at the end of her “California,” “Will you take me as I am? Will you?” She says, “I hope that I’ve transgressed—that’s what a self-made original like Mitchell would have wanted.” Powers does the dance, she twirls Mitchell in her very own loops within loops.

Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell is now available wherever books are sold.

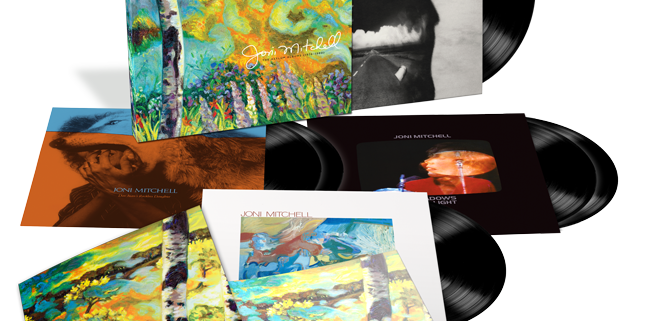

Meanwhile the latest official Joni Mitchell newsletter reminds us that we can still purchase all her Asylum albums (left) at her official web site

acknowledgements

The prime source for this piece was first published in Paste in June 2024 and was written by Madelyn Dawson, a music and culture writer based in New York. She currently goes to school in Connecticut. You can find her everywhere @madelyndwsn.

Paste on line does not need recommendation from the likes of us and we do not seek to exploit their excellence. Instead we hope our readers will remember to employ Soundtracks and Detours and PASS IT ON, our not-for-profit blogs as a launch pad to some of the best writers and the best sites out there covering the arts.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!