RUMOURS OF ACOUSTIC GUITAR REVIVAL

Norman Warwick hears

RUMOURS OF ACOUSTIC GUITAR REVIVAL

Geoffrey Himes has written recently at Paste on line about what sounds like a history of the acoustic guitar in his particular genre of American music. However, The Old Curmudgeon, as he self deprecatingly describes himself actually delivered an article which noted the reappearance of the instrument at recent major festivals and actually seemed to predict a brighter future for the instrument, and those of us who love its sound.

When Arthel Watson was growing up in Deep Gap, North Carolina, his chosen instrument, the acoustic guitar, was an afterthought in the string bands of Appalachia. It just wasn’t loud enough to be heard next to a fiddle or a banjo if there was no microphone on stage—or even only one. As a result, the guitar was rarely given a solo and mostly relegated to rhythm chords. But Watson (left), nicknamed Doc after Sherlock Holmes’ sidekick, wasn’t satisfied with a secondary role. He joined a band without a fiddler and learned to play fiddle tunes on an electric guitar as briskly and as crisply as any violinist. And when he got a microphone of his own, he could play the same licks on an acoustic guitar, giving them that hollow, wooden sound that somehow resonates better with mountain music.

It was a revolutionary moment that freed the acoustic guitar from background duty in string bands and moved it to the foreground. Soon steel-string guitarists such as Tony Rice, Clarence White, John Fahey, Leo Kottke, Chris Smither, Norman Blake, David Grier, David Bromberg (right) and Jorma Kaukonen were enjoying robust careers in the ‘60s and ‘70s. That boomlet petered out eventually, but now we’re witnessing a resurgence of younger acoustic-guitar soloists. Molly Tuttle, Bryan Sutton, Uwe Kruger, Dan Tyminski, Billy Strings, Yasmin Williams, Cody Kilby and Trey Hensley are not only technically dazzling but they’re also putting new twists on an old tradition. Many of them were on display at this year’s Merlefest, the annual Americana festival co-founded in 1988 by Watson himself and named after his son Merle, a gifted guitarist who had died in a 1985 tractor accident. (Merle was named not after Merle Haggard but after the great country guitarist Merle Travis).

Except when a pandemic is raging, Merlefest is held on the steep, hillside campus of Wilkes Community College in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, the last weekend in April when the dogwoods are blooming. While country, rock, blues and singer-songwriter acts are sprinkled in, the emphasis remains on bluegrass and old-time string-band music. Even though Doc Watson died on May 29, 2012, exactly a month after his final performance at Merlefest, his presence was still felt throughout this year’s festival. Old-timers such as Roy Book Binder and Steve Lewis spoke from the stage about playing with Watson and his openness to all genres and sounds. Baby boomers such as Sam Bush and the Kruger Brothers fondly recalled the times Watson invited them to his house for iced tea and hours of picking.

Youngsters such as Presley Barker and Liam Purcell admitted that growing up in the same area as Watson had nudged them in the direction of string-band music. And Old Crow Medicine Show (left) remembered their early days busking on the streets of nearby Boone, North Carolina, when Watson came to hear them and give them some much needed encouragement. The band tried to recreate that pass-the-hat experience by inviting Boone’s veteran tap dancer Arthur Grimes to join them on stage. “If you think your music has influenced other musicians,” Watson told us at a 2001 press conference, “that’s like the applause when you walk onto the stage. If an audience responds—and you can tell by the reaction if they’re listening or not—it doesn’t matter if it’s 20 or 10,000 people out there. Of course, it might be different for a sighted person.”

An eye infection robbed Watson of his sight before he turned two. But he never used it as an excuse for anything—instead thinking of it as something that bonded him with others in a similar situation. During the press conference, for example, he spoke how excited he was to play with a young blind fiddler named Michael Cleveland. 23 years later, Cleveland returned to Merlefest as a member of banjoist Bela Fleck’s all-star band, My Bluegrass Heart. Cleveland’s virtuosity had only grown since his days as a young prodigy, but more importantly his playing has gained an emotional depth it had never had before. Now, when given a choice between playing fast and playing a slower, darker harmony, he is more likely to do the latter.

Standing nearby on Merlefest’s Watson Stage was Bryan Sutton, the tall guitarist who made his name with Ricky Skaggs’ band before becoming a top Nashville session musician. But he is clearly a Watson apostle, a flatpicking expert who can articulate each note and put it in the proper sequence to tell a story. Sutton, Cleveland, Bela Fleck (right) ), mandolinist Sierra Hull, bassist Mark Schatz and dobroist Justin Moses devoted the first half of the set to Fleck’s compositions, which mixed bluegrass and chamber-music elements into a challenging whole. The second half showcased the title track of their latest album, Rhapsody in Bluegrass, Fleck’s arrangement of the George Gershwin classic for bluegrass instruments. It sounds like a gimmick, but it worked much better than expected. The string band gave the robust melody a much different tonality but with the same anthemic lift of majesty.

“I might play Kris Kristofferson’s ‘For the Good Times,’” Watson said in 2001 when asked about interpreting well known compositions, “but I won’t try to copy Chet Atkins on the Ray Price version. I just play what comes to mind. If you play what you feel, music is a conversation between people who respect each other. You’re feeling the song or you’re feeling the idea of the song—it’s the same thing.”

That kind of conversation was happening when Molly Tuttle (cover photo) and Golden Highway played the first night of Merlefest this year. The five gifted musicians also interpreted well known pieces (the Rolling Stones’ “She’s a Rainbow” and Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit”) by passing the familiar hooks around and adding a new twist with each solo. One long medley began with “Alice in Bluegrass,” Tuttle’s own telling of the Lewis Carroll story, then shifted into the Airplane version, “White Rabbit.” That evolved into an extended psychedelic jam before segueing into a straightforward version of the traditional bluegrass number, “The Train That Carried My Girl from Town.” The medley seemed designed to prove that originals and standards, recent rock influences and ancient string-band influences are all necessary ingredients in the stew.

Tuttle looked over her left shoulder at the smaller Cabin Stage—an actual log cabin porch, where supporting acts play while there’s a changeover on the main stage. She had first played at Merlefest on the Cabin Stage when she was competing in the festival’s songwriting contest as an 18-year-old girl playing with her father. She won the contest, and she has kept growing as a writer. Her songs about heartbreak, cannabis and the American landscape were highlights of the set as they have been on her recent albums. “She’s writing the songs,” banjoist Kyle Tuttle told the crowd. “She’s singing the songs, and she’s paying tribute to Doc Watson by playing the snot out of the guitar.”

Among the most reliable treats of Merlefest are the Kruger Brothers. Jens and Uwe Kruger grew up in Switzerland, led a blues-rock band in Germany and followed their interest in American roots music to the northwest corner of North Carolina in search of Doc Watson. “Our first Merlefest was in 1997,” Jens told this year’s audience at the college’s Walker Center, “so this is our 25th. We met Doc Watson there. He invited us up to his house, and we played all day. We liked this area so much that we moved here. Now I play on my back porch, and the raccoons come to hear me play, and sometimes they sing along. One I call Stripey and the others I call Stars—Stars and Stripey. But that sound of the woods and the raccoons is what makes Doc’s music so distinctive.”

The brothers then played “The Cuckoo Bird,” the traditional American folk song that Watson recorded so definitively. The Krugers took it at a brisk tempo, with Uwe’s guitar solo nearly matching Jens’s quicksilver banjo runs. And it was Uwe’s relaxed baritone voice that lent plausibility to the strange but compelling lyrics: “My horses, they’re hungry, and they won’t eat your hay. I’ll ride on that little bird, and feed ’em on my way.” No wonder Watson has been quoted as saying, “I love playing with the Kruger Brothers.”

The two brothers played three different shows on three different stages with three different setlists at this year’s event. Jens is such a dazzling banjoist—he was hired by Bill Monroe and awarded the Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass Music—that it’s easy to overlook just how good a guitarist his older brother Uwe is. But when Uwe paid tribute to Watson on “The Cuckoo Bird” or to the recently departed Dickey Betts on “Blue Sky,” he maintained a fluidity in his string of notes even as each one was sharply defined.

Watson himself was willing to take on a wide range of repertoire. “I love bluegrass,” he said in 2001, “but I don’t think of myself as a bluegrass musician. I call what I do ‘tradition-plus.’ I might do a Crystal Gayle song or the Moody Blues’ ‘Nights in White Satin.’ If a song has something to say, it might be a song I have to learn.”

Dan Tyminski is best known for singing the vocals that came out of George Clooney’s mouth in the movie O Brother, Where Art Thou? As a member of Alison Krauss and Union Station, Tyminski is the second vocalist, mandolinist and acoustic guitarist. As the leader of his own band, however, his guitar picking is showcased as never before. This was especially obvious at Merlefest when he performed “Where You Been Gone So Long,” a track from Tyminski’s 2022 tribute EP to Tony Rice (a project that featured Molly Tuttle and Billy Strings). Tyminski may have the best balance between singing and playing since the young Rice himself.

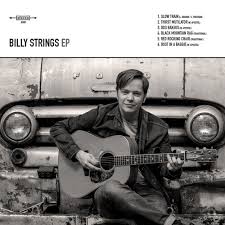

The 80-year-old Roy Book Binder sat in a chair, his eyes dancing between a straw fedora and a salt-and-pepper walrus mustache as he told stories of his long-ago encounters with Watson and blues legends Pink Anderson and the Rev. Gary Davis. Book Binder favored the talking blues and ragtime picking of the Carolina bluesmen, and he provided a rare link to a pre-Beatles era that has few surviving musicians. It wouldn’t be right to do a roundup of today’s acoustic guitarists without mentioning the most innovative of the bunch—Yasmin Williams—or the most popular—Billy Strings. Both of them have been featured at Merlefest in the past, but not this year.

Williams (left), though, performed at Knoxville’s Big Ears Festival a month before Merlefest. She played sitting down, as always, so she could trigger foot-pedal percussion. Sometimes her acoustic guitar rested on its side in her lap, but more often it lay on its back, so she could tap on the strings as if they were keys on a piano. Sometimes she attached a kalimba—the African thumb piano—to the top of her guitar with Velcro and alternated between the two instruments. Sometimes she used a tiny hammer to reinforce the percussive aspect of her music. She’s restlessly experimental, but her unusual techniques are not an end unto themselves. They are always a means to expressing a feeling via melody and timbre. At Big Ears, for the first time in public, she played her latest acquisition: a white, double-neck, Gibson electric. Once again, she laid it flat in her lap and tapped out unusual sounds in search of a melody neither she nor we had heard before.

.

Billy Strings (right) was a face on many T-shirts at Merlefest, but the last time I saw him was October 2023 at Baltimore’s CFG Bank Arena, a basketball arena. It’s not often you see an acoustic guitar in such a setting except as a strum-along prop for a singer. But this crowd—not a sell-out but respectably large—was there to hear Strings’ solo on his hollow, wooden instrument

It’s difficult to hold the attention of so many people with the subtleties of an acoustic guitar, but Strings does it. Sure, it helps that he sings his likable songs and that he often adds electronic effects to the sound of his instrument. But mostly he mesmerizes by heeding the lessons that Jerry Garcia left behind. It’s not about speed; it’s about the ability to link notes together in a chain that’s as pleasurable as it is surprising. That’s not easy to do, because many things that are enjoyable are predictable and many things that are unexpected are discomforting. It’s hard to find that sweet spot in between, but Strings consistently does.

The festival’s most memorable moment came at the end of Molly Tuttle’s set when she introduced the title track from her 2022 breakthrough album, The Crooked Tree, by telling a long story about the costs and benefits of being different from the rest of society—like a misshapen tree in a forest who may be mocked but who is ultimately passed over by the lumberjacks. Tuttle then personalized the story by connecting it to her own childhood when the alopecia areata disease caused all her hair to fall out and never grow back. She described how years of being teased and pointed out eventually gave her the strength to go her own way. “I realized my greatest fear was my greatest superpower,” she said. With that, she whipped off her red wig to reveal the bald dome of her head with its two dangling silver earrings. It was a surprising look when first encountered but surprisingly beautiful in a short while. And that’s how she delivered the final two songs of the show. And the courage of that move was reflected as much in the singular personality of her guitar playing as in the authority of her singing.

acknowledgements

The primary sources for this piece was written by Geoffrey Himes for Paste on line magazine Other Authors and Titles have been attributed in our text wherever possible.

Images employed have been taken from on line sites only where categorised as images free to use.

You and your like-minded, arts loving friends will surely see Paste as an indispensable source of knowledge.

For a more comprehensive detail of our attribution policy see our for reference only post on 7th April 2023 entitled Aspirations And Attributions

.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!