there will be an answer: LET IT BE

there will be an answer: LET IT BE

a plea from The Beatles? asks Norman Warwick

To celebrate May´s exclusive, restored release of the documentary LET IT BE on Disney+, Paste On Line spoke with the legendary director about the film and its unearthing after more than 40 years of dormancy.

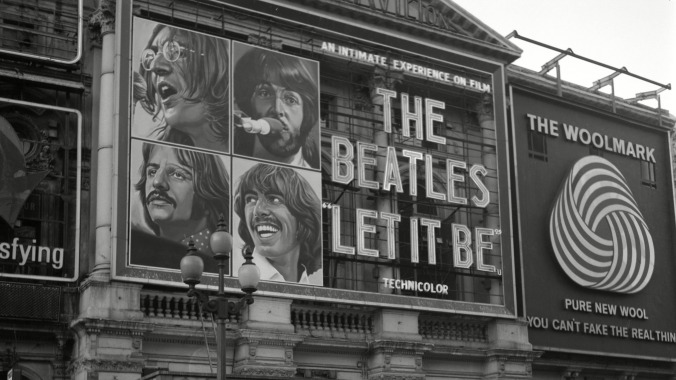

54 years ago on May 13th, 1970, director Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s (shown left with roof top Beatles) feature documentary Let It Be had its world premiere in New York City. Despite being one of the most covered bands in history, Let It Be was the first film to document and reveal the Beatles’ behind-the-scenes process of writing and recording their songs. The compositions, captured over one month in early 1969, would end up on Abbey Road and what would be their last studio album, Let It Be. At any other time in the band’s meteoric run, Let It Be would have been cause for pure celebration—except the release came less than a month after on-going band-mate friction resulted in Paul McCartney announcing his formal separation from the band and the Beatles’ dissolution. So, Let It Be landed more like a funeral dirge for critics and fans to pick apart in divining why the band was no more.

Despite the film winning an Academy Award for Best Original Score (or, Original Song Score, as it was once known), Let It Be basically disappeared from the zeitgeist—until it received a muddy VHS and laserdisc release in 1981. For the next four decades, Beatles fans had to pass around their terrible dubs of that print until Peter Jackson shocked the world in 2021 with his pristine restoration of Lindsay-Hogg’s footage remixed into the heralded three-part miniseries, The Beatles: Get Back.

Jackson got the approval of McCartney, Ringo Starr, Yoko Ono and Olivia Harrison to edit the material into a much broader contextual tapestry of the final creative days of the band. The restoration literally produced a brighter and more thorough perspective of their complex dynamics—and it also opened the door for today’s re-release of Let It Be, featuring Jackson’s restored footage and pristine mix by Giles Martin and Sam Okell. Now, historians, critics and fans alike will get to assess the film anew and discover its merits.

After a diverse 50-year career in the arts as a director for television, theater and film, Sir Michael Lindsay-Hogg (now 84) says that he’s glad to see Let It Be getting a second life so many years after its release. “It does feel like it’s time,” he explains of the doc’s 40-years in repose. “I never would have thought it would take so much time. I never thought in 1974, when it was off the market, that it would be 50 years which is a long time for it to come out again. We’re two generations down the line, so people can be seeing it now, who were not even born in the 21st century.”

I can remember that fans were becoming increasingly aware that all was not well in The Beatles at the time, but very few of us ever feared that the band would split up. Now of course I look back on the lyrics of Let It Be as being something more than the quasi-religious, cemi gospel song that it was. Today I read it, or at least interpret it in open reading, as a plea to not ´murder to dissect´as Wordsworth would have had it. Perhaps Let it Be can now be heard as The Beatles´ plea to let their work speak for itself?

Post-Let It Be, Lindsay-Hogg’s short-format directing of music promos helped lay the groundwork for the music video era. He made his mark working with the Rolling Stones, Elton John and even reuniting with Paul McCartney to make music videos for his post-Beatles band, Wings. Through that on-going friendship, the director admits he often asked McCartney about getting Let It Be released from limbo. “Mainly, Paul and I talked a lot about it over the years. I sometimes think if he hadn’t seen me for a while, he might back away from me like he knew I’d be asking, ‘What’s gonna happen with Let It Be?’” he jokes about his obstinance.

In those conversations, Lindsay-Hogg says the reasons for the doc’s dormancy, from the Beatles’ corporate entity, Apple Corps Ltd., changed often. However, he debunks the particular theory that it was any specific band member who nixed its release. “One of the big reasons is that it was taken off the market for disagreement about music rights, regarding who owned the music rights to the VHS versus the movie studio rights versus EMI,” he explains.

Known as promotional videos, Lindsay-Hogg says they were the next evolution of the French-created Scopitone videos, which were found in quarter-fed players (think visual jukeboxes) in bars around the world. “They were mainly French artists and they’d wear very, very garish colors,” he chuckles. “Everyone is dressed in pink and lime green. They were cute little things. But that was the first [music] video that I’d ever seen.” The promotional videos allowed bands to fill in the gap between tours, or expand artistically outside of the television performance shows that were very stage focused. “The only bands who could afford the videos, in England anyway, were the Beatles and the Rolling Stones,” Lindsay-Hogg continues. “They could afford them not only financially—they weren’t expensive—but they could afford to tell the television shows that if you want us, you play the video. The TV shows were not only in England, but they’d be in France, they’d be in Spain, so therefore, they didn’t have to travel anymore to France, Spain or Australia because of videos.”

Lindsay-Hogg says the Beatles stopped touring in 1966 and then became innovators in the medium, working with director Joe McGrath on promo videos for songs like “Help” and “We Can Work It Out,” amongst others. As a director during that early era of music video creativity, Lindsay-Hogg says he was particularly proud of “Angie” and “It’s Only Rock and Roll,” both of which he directed for the Rolling Stones, and “Hey Jude” for the Beatles. “That one added an audience at the end,” he says of the Beatles’—and McCartney’s—opus. “The influence of it is what became Let It Be, because Paul thought they should play to an audience again and that they shouldn’t be too much in their ivory tower. During the breaks when we were shooting ‘Hey Jude,’ the [band] had nothing else to do but play to the crowd which we got to be in the video. So they thought, ‘Maybe we can do it again,’ which is what gave [Paul] the idea to do a concert. And when that fell apart, that’s what turned into the documentary.”

By the end of Lindsay-Hogg’s career, his C.V. was stacked with concert films he directed that remain all-timers in the genre. From The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus to Simon and Garfunkel’s The Concert in Central Park, he was there to capture landmark events in the lifespans of many legendary musical acts. Asked where Let It Be ranks in retrospect, Lindsay-Hogg says it remains a “very strange project” because of how it evolved from a concert to a television special to eventually a documentary feature. “It turned into a documentary pretty much overnight and a documentary is very different—because the product you end up with is going to be totally different,” he explains. “It’s not going to be a one shot concert. It’s going to have a lot of aspects of behavior, making music and doing all those things together, so that gave me a little bit of pause.

“Also, because I realized that no one had ever shot the Beatles rehearsing,” he continues. “You have this extraordinary group of four musicians, and except for bits and pieces, no one ever shot them rehearsing. And so I thought, this is a kind of responsibility I have because of who they are. If I can show how they create their songs, and what a struggle it is, or how easy it is, that’s part of what people would be interested in.” However, once the documentary format was finally agreed upon by the band, Lindsay-Hogg knew that just rehearsal footage strung together wasn’t going to be a satisfying film. “It would have no payoff,” he points out. “So, we talked about various concert ideas we had, and none of them were quite right. There needed to be some kind of playing music conclusion to the movie. There was something complete about [playing] complete songs, not rehearsed items anymore. And I woke up one morning, and I thought, ‘Well, what about the roof?’”

When he posed that to the band that day at lunch, Lindsay-Hogg says they were confused. “Paul said, ‘Do what on the roof?’ And I said, ‘A concert on the roof,’” he explains. “Although they didn’t all agree they were going to do the roof [concert] until after we were supposed to be on the roof, it all took place pretty quickly in about four or five days.” While the Let It Be documentary languished in canisters for decades, the rooftop concert that ended the film took on a life of its own—as not only a seminal performance for the band, but their last public concert together. Aesthetically, too, that whole section of the film went on to influence countless bands and concert films for years.

“From my point of view, I had to figure out how to shoot it,” Lindsay-Hogg says, looking back at the concert section. “Like, how many cameras would be on the roof? And how I’d be sure they all were pointing in the right direction because we didn’t have ear phones for communication. We had hand signals. And also thinking, what’s the effect of this going to be on the rest of the world down on the street? I wanted the music to be louder than it was so it would go to Regent Street and Oxford Street, and we’d get all of London. But the technical people were afraid of getting it all back on the mics. And, it was a windy day.”

Some of the most memorable scenes in the sequence is cinema verite footage cut into the concert of the gathering onlookers, and eventually the police who arrived to shut it all down. Lindsay-Hogg says all of that came out of brainstorming what was likely to happen on the day, and then being prepared for it. “Because it’s a conservative area on Savile Row, mainly with high end men’s tailors, there might be a complaint from the people in the shops,” he remembers thinking. “A complaint might mean that the police would come for disrupting business. And if the police come, then what do I have to do? We were going to stall the police if they came, but then they’d be standing around in the lobby of the building. So, I built a little hut in the lobby with a two-way mirror so I’d have a camera back there which the police would just think was a mirror. You had to think about it all as we knew it was going to be one shot only.”

Going back to its production, Lindsay-Hogg says Let It Be was always a film beset with unexpected disappearances. He couldn’t even get daily footage to review in a timely fashion. “Funnily enough, it took a long time to see [footage] because we were having sync problems,” he says. “It took like, six weeks before it was synced up.” When he did review everything, he still remembers his initial impressions. “I felt that on the roof, they were wonderful,” he continues. “It reminded them of what it was really like to be a great rock ‘n’ roll band. When we went downstairs after it was over and everyone had a cup of tea, they were very excited. They felt they’d done something. They hadn’t toured for three years and there was a discussion in the group room, would they ever tour again? Would they just make music? You had a sense that they felt, whether they’d do it again, no one knew, and they didn’t as it turned out. But they felt this time had been great.”

Before Jackson’s restoration, Lindsay-Hogg says it was decades until he even saw a copy of Let It Be again. “I had a copy from Apple, watermarked probably in 2012,” he shares. “But it wasn’t a good copy. It had no vibrancy to it. And one of the things that I feel good about with how Let It Be looks now is that it’s just a very vibrant movie. I don’t mean visually it’s vibrant. I mean, it’s vibrant emotionally. And that’s why I kept being the nudge of all time,” he laughs about his pestering for its release. “‘Oh, God, here comes Michael again! Let’s hide!’”

And, if that were true, it might support my own feelings at the time that although the lyrics of the single Let It Be seemed cemi spiritual and personal and also quasi religious, perhaps the phrase, Let It Be, was actually a request from The Beatles to fans and media alike not to ´murder to dissect´ as Wordsworth put it.

Had my generation and our media not been so intrusive then, John, Paul, George and Ringo might have been able to resolve their issues in peace and quiet.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!