DOES TRUTH MATTER?

are biopics fact or fiction and are songs true or false

DOES TRUTH MATTER?

wonders Norman Warwick

Given that the last three films I have watched in a cinema have been versions dubbed into Spanish, of which I speak not one word, were all biopics, I was intrigued by an article in Paste on line magazine by xxx entitled Biopics: Fact Or Fiction.

The three films I ma referring to were Aretha (of Ms. Franklin), Elvis and in a sharp turn, Oppenheimer, to which we shall return later in this article. First, though let´s examine what Kayleigh Donaldson had to say.

As we head into the final months of 2023, it’s time for the time-honoured tradition of awards season. From now until March, expect lots of actor schmoozing (SAG-AFTRA strike approved or otherwise), studio hype and capital-D Discourse. There are many parts of awards season that have become painfully familiar to us. There are genres of films and brands of performance that are as ingrained into this timeline as actor roundtables and pretending to care about the Golden Globes. The Academy’s tastes are so unchanging that there are movies we declare to be Oscar favorites from the moment they’re greenlit. Nothing exemplifies that predictability better than biopics.

To say that the Oscars love biopics feels like an understatement. They’re addicted to them, so quickly won over by this most middlebrow of genres and the staid structure of storytelling they offer. Acting in one certainly seems to be the easiest way to win a little gold man. Since 2000, 50 of the 115 performances nominated for Best Actor were for playing real people. This current season doesn’t seem like it’ll be short of competitors to add to those statistics. The current Best Actor front-runners include Cillian Murphy as Oppenheimer, Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein in Maestro, Colman Domingo in Rustin and Joaquin Phoenix in Napoleon. And that only scratches the surface of the biopic glut of 2023. Consider: Nyad, Priscilla, Ferrari, Freud’s Last Session, The Iron Claw, Air, Blackberry, One Life, Killers of the Flower Moon and Bob Marley: One Love.

Dennis Bingham, who wrote extensively on the study of biopics, once described them as “a respectable genre of very low repute.” Essentially, the biopic is characterized by its narrative safety. These films generally don’t take risks, and when they do, they often stop being defined as a biopic. You know what you’re getting when you go to the cinema to see the latest glossy dramatization of the life of a singer you love, for example. Nobody leaves Rocketman surprised by what they saw (of Elton John). These are, generally speaking, stories for the masses. That’s not a bad thing. Many wonderful biopics have been made. Yet it’s tough to deny, especially in the past two decades or so, how the genre has been distilled into a gruel-like solution that sands away harsh truths in favor of corporate preservation. This usually means that the truth is smudged away, bit by bit.

The purpose of a biopic, generally speaking, isn’t to detail history as it actually happened. You’d be hard pressed to find an example of one that sticks to the documented truth without wavering (a rare exception to the rule would be David Fincher’s Zodiac, which is as close to reality as the director could get given the source material available). A lot of these changes are necessary for the basic act of narrativizing. Life doesn’t unfold in a three-act structure, after all. Frequently, events need to be condensed. Names changed. Complicated moments simplified. You need to give your actors that Oscar clip moment. And that’s all assuming that the sources available for the adaptation process are accurate. History is written by the victors, and biopics strengthen that resolve.

Sometimes, changes to history in biopics are pretty inconsequential. Other times, it feels like outright malpractice, such as Bohemian Rhapsody‘s grotesque decision to change around the timeline of Freddie Mercury’s AIDS diagnosis to motivate him to perform at Live Aid. In Nyad, Netflix’s take on swimmer Diana Nyad’s solo swim from Cuba to Florida, she is of course the heroic go-getter who does what no one else before her has, and at the age of 64. Like Bohemian Rhapsody, Nyad was made with the full cooperation of its living subjects. That means that the filmmakers were never going to be able to tackle the many doubts from the open water swimming community over whether or not Nyad actually succeeded (her swim has still never been formally ratified by any recognized marathon swimming organization).

This is often a problem that befalls biopics, typically those centered on musicians. In order to get the rights to the music, which is a key attraction to audiences, the studios and directors must adhere to the demands of the people involved or the corporate entities who own their back catalogues. It’s easier to sell a soundtrack when you don’t portray the subject faithfully, even if their story is well-known. Note how Priscilla, which centers Elvis’ wife over the King himself, couldn’t get the rights to any of Presley’s music because Authentic Brands Group, which owns 85% of the Presley estate, said no to director Sofia Coppola.

As she told The Hollywood Reporter, “They don’t like projects that they haven’t originated, and they’re protective of their brand.” By contrast, Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis, made with total cooperation of ABG, used all of his music. It’s no coincidence that the latter film downplays Presley meeting Priscilla when she was 14, while Coppola’s film delves into the oft-deified singer’s darker side and mistreatment of his wife. In Elvis, Presley has little power. In Priscilla, his manipulations are far more evident. It’s not hard to see which narrative sells more records.

Many biopics have no interest in truth, often for fascinating reasons. Consider I’m Not There, Todd Haynes’ Bob Dylan film where six very different actors across lines of gender and race played the singer at various points in his career. Decades before that, Haynes told the story of Karen Carpenter through an unauthorized short that used dolls rather than humans, all the more effective to convey the late musician’s lack of autonomy during her life.

Ken Russell’s film about composers like Liszt and Mahler embraced a kaleidoscopic approach to better convey the power of their music rather than detail their lives as expected. Such films eschew the biopic’s patterns in hopes of finding the truth of their subjects through something more visceral than a beat-for-beat documentation of their childhoods. Surely someone who has made themselves as deliberately unknowable as Bob Dylan is better understood through a film that embraces that element, rather than hopes to dissect it.

The matter of truth is no less prickly when dealing with subjects who have been dead for quite some time. Biopics such as Napoleon deal with eras of varying levels of historical documentation, and there’s far more leeway for storytellers to rearrange events and details for their own purposes. Do you portray Bonaparte’s battles as noble or genocidal? Is he a despot or a genius? Director Ridley Scott has never had much time for sticking to the facts if he feels the narrative could do better. The Last Duel, his best film in years, tackles a real-life event, but uses it more as a foundation for a wider examination of rape culture than as a copy-paste of centuries-old reports.

Generally speaking, audiences are more forgiving of such changes when they’re not emotionally or intellectually attached to the truth, and a few hundred years of distance always helps in this regard. Scott himself, when criticized by historians over seeming inaccuracies in the Napoleon trailer, responded succinctly: “Get a life.”

They say that truth is stranger than fiction, but it’s also frequently far more interesting. Bohemian Rhapsody greatly downplayed Mercury’s life (and his queerness) to more fully position him as a sad gay cautionary tale.

The obvious issues and consequences of Jerry Lee Lewis marrying his adolescent cousin are distilled to a trite soap opera, and mean attack on the singer himself, in the abysmal Great Balls of Fire. Stardust managed the impossible by making David Bowie boring, so devoid of curiosity and vibrancy was its approach to a true icon. Capturing lightning in a bottle is half the challenge for a biopic, and if you fail, your audience will just wonder why they were ever supposed to care about this famous person in the first place.

Yet this feels somewhat inevitable when you stick to the rote and endlessly repeated conventions of the genre. They do not allow much room for true perception or challenges. Nor do the desires and demands of the current entertainment corporate machine want it to. The vast majority of modern biopics are brand extension exercises, designed to sell records or books or hologram tours. And they work as intended. Bohemian Rhapsody made over $900 million worldwide, won four Oscars and, according to Billboard, saw on-demand streams of Queen’s music triple in the six months following the movie’s release. What does truth matter when money talks louder?

The future of the biopic is an expected one, a path set on rails as thoroughly as the genre itself. There will always be exceptions, although films that deviate from the norm do so with such force that one wonders if they can even still be called biopics. For things to truly change, a celebrity or their estate will have to willingly give up creative control and allow a storyteller to actually tell the truth. That seems unlikely when there’s so much cash on the line. The game of fame is built on embracing the fun lie over the dark truth. Why should the biopic be any different?

Kayleigh Donaldson is a critic and pop culture writer for Pajiba.com. Her work can also be found on IGN, Slashfilm, Uproxx, Little White Lies, Vulture, Roger Ebert, and other publications. She lives in Dundee.

Sidetracks and Detours urge you to seek out the Paste On Line posts and seek out Kayleigh their many other excellent writers

Driving home, after viewing the Oppenheimer film I said to my wife, Dee, that I was definitely going to read an Opperheimer (auto?) biography to solve some of the puzzles I was confronting after seeing the film

I´m not sure that Dee was paying a lot of attention to me, preferring to attend to her massive tuna salad and a glass of dry white that wasn´t much smaller.

In the end she said, ´leave it until we see Larry and Liz, next week. Larry will either already have a book or placed an order since seeing the film´ !

When we met Mr. & Mrs Yaskiel on the lunch time of the following Wednesday at Café en La Plaza in Peurto Callero the conversation flowed freely and we learned that they had actually seen the film four nights earlier than us in one of the smaller studios. I said that the film had left me with more questions than answers. So, too, with Larry it seemed, who said he had rushed on to his computer as soon as he had arrived home from the film to do further research on Oppenheimer, the man and the film, as soon as possible.

´It was the longest Wikepeadia entry I have ever seen´, he told me.

As it happened I had noticed that too, but I had been able to extrapolate from its density that the film Is actually based on American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, a 2005 biography of theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, the leader of the Manhattan Project which produced the world´s first nuclear weapons. The book was written by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin over a period of twenty-five years. It won numerous awards, including the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography.

The book has now served as inspiration for Christopher Nolan‘s 2023 biographical film Oppenheimer

When I sent my thanks to Larry Yaskiel for alerting us to the showing Of Elvis The Movie in Arrecife, his immediate response was a loud cry of ´false alarm´. The English language versions had already been screened, he said, so maybe we should hold our horses. (Larry knows how barren is our Spanish vocabulary !). Nevertheless, I e-mailed back jokingly to say that a Heartbreak Hotel is a Heartbreak Hotel in any language, so we´d give it a go.

His response was, ¨Well, please remember that Elvis (in English) has left the building ´

I couldn’t compete with that brilliant reply, so come the Thursday night, off we set for the five o´clock showing at Dee´s favourite cinema, (right) having checked up on what others had been saying about the film.

Whenever Rotten Tomatoes reviews are thrown at a film they tend to be contained in a tine and can be quite hurtful. Nevertheless, even they were offering praise to the film.

Flashes of colour, lightning cuts, and the camera spins and needle drops are at times overwhelming, but it’s an overall enjoyable experience that washes over you in waves of excitement said a Chicago reader of Rotten Tomatoes.

Elvis is hyperbolic, one-dimensional and ludicrous – but as high-excess cinematic myth-making, it’s a blast. said the very credible Uncut magazine.

The Independent had wondered, ´If we were to pull back the curtain on Elvis Presley, what would we even want to see? A soul stripped of its performance? Something cold and real behind the kitsch? I’m not convinced. America’s pop icons aren’t merely shiny distractions. They’re a culture talking back to itself, constantly interrogating its own ideals and its desires. I don’t think who Elvis was is necessarily more important than what Elvis represents. And, while you won’t find all that much truth in Baz Luhrmann’s cradle-to-grave dramatisation of his life, the Australian filmmaker has delivered something far more compelling: an American fairytale

The Independent had wondered, ´If we were to pull back the curtain on Elvis Presley, what would we even want to see? A soul stripped of its performance? Something cold and real behind the kitsch? I’m not convinced. America’s pop icons aren’t merely shiny distractions. They’re a culture talking back to itself, constantly interrogating its own ideals and its desires. I don’t think who Elvis was is necessarily more important than what Elvis represents. And, while you won’t find all that much truth in Baz Luhrmann’s cradle-to-grave dramatisation of his life, the Australian filmmaker has delivered something far more compelling: an American fairytale.

I am the man who gave the world Elvis Presley,” utters Tom Hanks’s Colonel Tom Parker, his manager, (left) as the curtain rises (literally) on Luhrmann’s expansive, rhinestone-encrusted epic. “And yet there are some who would make me out to be the villain of this story,” he adds.

Parker, who saw early promise in Elvis’s almost certainly unintentional politically radical blend of country and R’n’B, slyly positioned himself as the sole overseer of the star’s creative enterprise – the man who won him a recording contract with RCA Records, who secured his merchandising deals and TV appearances, and who navigated him through a fairly brief but bountiful acting career. But Parker took far more in return. In 1980, a judge ruled that he had defrauded the Presley estate by millions. Some even blame him for pushing an overworked Elvis to the brink and ultimately contributing to his death.

To say that Elvis isn’t really so much about the real Elvis might sound like it’s taking the pressure off of Butler’s performance. But that’d be an entirely unfair judgement of what’s being achieved here – an impersonation of one of the most impersonated people on the planet, that’s at times uncanny without ever coming across as parody. Sure, Butler has the looks, the voice, the stance and the wiggle nailed down, but what’s truly impressive is that indescribable, undistillable essence of Elvis-ness – magnetic and gentle and fierce, all at the same time.

It’s almost odd to watch a performance so all-consuming that Hanks – the Tom Hanks – feels like an accessory. He’s all but buried underneath layers of prosthetics and a pantomime Dutch accent, seemingly cast only so that the warm smirk of America’s dad can trip a few people into questioning whether he’s really the villain of all this. Butler makes a compelling argument for the power of Elvis, at a time when the musician’s arguably lost a little of his cultural cachet. So does Luhrmann. So does the soundtrack, which is packed with contemporary artists (Doja Cat’s “Vegas” has sound of the summer written all over it). And while not everyone will be convinced by their efforts – I know that I’m ready for Elvis to be cool again.

To summarise, the film explores the life and music of Elvis Presley (Austin Butler), seen through the prism of his complicated relationship with his enigmatic manager, Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks). The story delves into the complex dynamic between Presley and Parker spanning over 20 years, from Presley’s rise to fame to his unprecedented stardom, against the backdrop of the evolving cultural landscape and loss of innocence in America. Central to that journey is one of the most significant and influential people in Elvis’s life, Priscilla Presley (Olivia DeJonge).

Aretha Franklin film, Respect was, to me, a broad brush stroke film that offered fewer answer than it raised questions, though we might have found more answers had weunderstood any of the Spanish language. Reviews at the time included one in The Guardian headlined its piece as ´One-note Aretha Franklin Chronicle Follows Every Biopic Beat´ which certainly seemed to be a condemnation by a faint praise.

Their reviewer, Peter Bradshaw wrote under the strap line ofthis biopic reduces the complexity of her upbringing and artistry to corny life lessons.

So are any bio-pics, biographies, autobiographies worth the plastic money we pay for them?

Whether or not songs can be trusted as reliable narrators is surely called into question by Frank Sinatra´s autobiographical interpretation of My Way, a song written by Paul Anka !

We were perhaps persuaded by the title Billy The Kid; The collected works but maybe Michael Ondaatje´s book captured the outlaw more accurately than most.

.

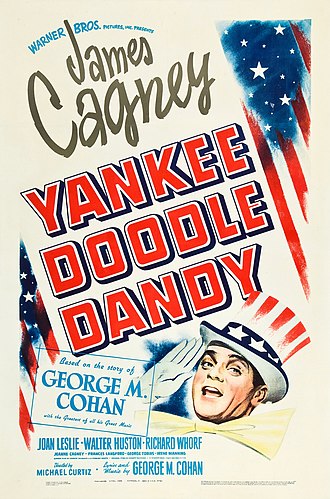

two biopics that have most impressed me in my sixty five years of watching movies did so by very different narrative styles. I speak here of Joe Hill and Yankee Doodle Dandy !

Yankee Doodle Dandy showcased the wonderful actor James Cagney in a biopic of American songwriter George M Cohan.

Yankee Doodle Dandy is a 1942 American biographical musical film about George M. Cohan, known as “The Man Who Owned Broadway”. It stars James Cagney, Joan Leslie, Walter Huston, and Richard Whorf, and features Irene Manning, George Tobias, Rosemary DeCamp, Jeanne Cagney, and Vera Lewis. Joan Leslie’s singing voice was partially dubbed by Sally Sweetland.

The film was written by Robert Buckner and Edmund Joseph, and directed by Michael Curtiz. According to the special edition DVD, significant and uncredited improvements were made to the script by the twin brothers Julius J. Epstein and Philip G. Epstein. The film was a major hit for Warner Brothers, and was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture, winning three.

In 1993, Yankee Doodle Dandy was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”, and in 1998, the film was included on the American Film Institute‘s 100 Years…100 Movies list, a compilation of the 100 greatest films in American cinema.

Even watching it with my dad as a little boy and a score of times in my adulthood, I knew that Yankee Doddle Dandy was piece of cinematic American jingoism, butany film that could vehicle that incredible soft show song and shuffle routine by Cagney as a shamed jockey, sad but defiant, told usall the truths worth knowing of humanity.

When I first heard The Ballad of Joe Hill sung by Joan Baez, I had no idea who Joe Hill (left) was but there was enough in the verses to suggest he was a brave man of substance. For that reason, and perhaps to impress a girl friend, I went to see a showing of he film in art house on oxfor Road in Manchester. Unless memory fails me that was the first and is still the only time I ever heard applause for a film as the credits rolled.

Nevertheless, Robert Ebert, the world-acclaimed film critic reminded me that ´There’s a scene toward the end of “Joe Hill” that seems to underline the movie’s shaky political and moral position. Joe Hill himself (a Swedish immigrant who became one of the most colorful and important organizers in the industrial Workers of the World) has been convicted of murder in Utah, and waits on Death Row. There is considerable doubt that he’s guilty. Even Woodrow Wilson tries to intervene on his behalf. But the Utah authorities want a victim. And in a Salt Lake City boardinghouse, three of Joe’s Wobbly friends sit silently. One finally says: “The question is — is he more good to us alive, or dead?”

A question asked by many a record label, of many of their artists, I would imagine !

We also discussed what constitutes Truth and whether whatever truth is really matters Truths is really matters on these pages earlier this year when we attended a live one-man performance by the actor John Malkovich (left) at the theatre in the caves, Jameso Del Agua, on Lanzarote. The show was described in advance as a reading of his new autobiography,….. that didn´t explain the two sopranos who came to the stage with him, nor the thirty piece orchestra that joined them

For ninety minutes, with occasional songs and music, the American actor extemporised on a story about a German serial killer that was so convoluted it became unbelievable. Malkovich seemed to hold up a sign with the word truth written on it, and then tore that paper to shreds. He demonstrated clever literary techniques that seemed almost to have been created to confuse; death of author and all that. Even as he became a guilty narrator before our very eyes and revelled in that role, we pardon ed him. Why? Because it was entertaining? It was entertaining certainly but it was also weary-making, trying to follow the invisible linear narrative and to feel afraid and lost in a plot that became increasingly disturbing. The audience was with him, rooting for him to make some sense of all this not only for our sakes but also for the sake of his own sanity. It was all frantic and frenetic no funny, familiar, forgotten faces or places,………….. but it turned out he had been using as his script the lines of the autobiography of a German murderer of thirteen women. Somehow, Malkovitch had misappropriated the slayer´s words and made them his own , even if by omission of sin: of pages, paragraphs, lines or words. It was all an incredible black magic trick that divided his audience, with some leaving talking about the performance of his autobiography and others of us wanting to find more about the German slaughterer he had spoken of. It was a gruesome, gut-wrenching and it was pure bloody genius. I´m not sure he told me one single truth all night but he gave us all we could require to build our own truth,…..but there were no instructions and no building blocks. If we wanted the Truth, then we had to find it for ourselves..

I know I haven´t any light on the question of whether the truth matters, so I turned on-line to Barnyard site site to see what it considers to be the top twenty biopics of all times. I didn´t agree with all the choices, but it would be true to say that all the films on which I ´ agreed with their selection were such good movies it became easy to forget the ´story´ was a. biograph. Whether that is a good thing or not, I don´t know buy Beautiful Mind with Russell Crowe as the brilliant mathematician John Nash, was scary, claustrophobic film that took us into the mind, full of demons, of a man with a persecution complex.

High on the site´s list, though, was one that is also top of my personal list of best biopics.

Schindler´s List tells the story (an interesting choice of word, that might have seen as pejerotive in the context of this discussion, but was obviously not intended to be so) of Oskar Schindler is a German businessman in Poland who sees an opportunity to make money from the Nazis’ rise to power. He starts a company to make cookware and utensils, using flattery and bribes to win military contracts, and brings in accountant and financier Itzhak Stern (Ben Kingsley) to help run the factory. By staffing his plant with Jews who’ve been herded into Krakow’s ghetto by Nazi troops, Schindler has a dependable unpaid labor force. For Stern, a job in a war-related plant could mean survival for himself and the other Jews working for Schindler. However, in 1942, all of Krakow’s Jews are assigned to the Plaszow Forced Labor Camp, overseen by Commandant Amon Goeth (Ralph Fiennes), an embittered alcoholic who occasionally shoots prisoners from his balcony. Schindler arranges to continue using Polish Jews in his plant, but, as he sees what is happening to his employees, he begins to develop a conscience. He realizes that his factory (now refitted to manufacture ammunition) is the only thing preventing his staff from being shipped to the death camps. Soon Schindler demands more workers and starts bribing Nazi leaders to keep Jews on his employee lists and out of the camps. By the time Germany falls to the allies, Schindler has lost his entire fortune — and saved 1,100 people from likely death.

The film starred Liam Neeson and Ben Kinglsey. It was a gut-turning but uplifting film.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!